Eosinophilic bronchitis

| Eosinophilic bronchitis | |

|---|---|

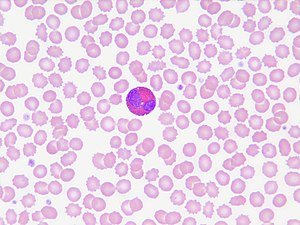

| |

| Eosinophils | |

| Specialty | Pulmonology |

| Symptoms | Chronic dry Cough |

| Causes | airway inflammation due to excessive mast cell recruitment |

| Treatment | corticosteroids |

Eosinophilic bronchitis (EB) is a type of airway inflammation due to excessive mast cell recruitment and activation in the superficial airways as opposed to the smooth muscles of the airways as seen in asthma.[1][2] It often results in a chronic cough.[1] Lung function tests are usually normal.[1] Inhaled corticosteroids are often an effective treatment.[1]

Presentation[]

The most common symptom of eosinophilic bronchitis is a chronic dry cough lasting more than 6–8 weeks.[3] Eosinophilic bronchitis is also defined by the increased number of eosinophils, a type of white blood cell, in the sputum compared to that of healthy people.[2] As patients with asthma usually present with eosinophils in the sputum as well, some literature distinguish the two by classifying the condition as non-asthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis (NAEB) versus eosinophilic bronchitis in asthma.[2][4][5] Non-asthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis is different from asthma in that it does not have airflow obstruction or airway hyperresponsiveness.[6] Along with eosinophils, the number of mast cells, another type of white blood cell, is also significantly increased in the bronchial wash fluid of eosinophilic bronchitis patients compared to asthmatic patients and other healthy people.[1] Asthmatic patients, however, have greater number of mast cells that go into the smooth muscle of the airway, distinguishing it from non-asthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis. The increased number of mast cells in the smooth muscle correlate with the increased hyperresponsiveness of the airway seen in asthma patients, and the difference in the mast cell infiltration of the smooth muscle may explain why eosinophilic bronchitis patients do not have airway hyperresponsiveness.[1] Eosinophilic bronchitis has also been linked to other conditions such as COPD, atopic cough, and allergic rhinitis.[2]

Pathophysiology[]

The number of eosinophils in the sputum samples of non-asthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis patients are similar to those of patients with asthma. In the sputum samples of those with NAEB, histamine and prostaglandin D2 is increased. This suggests that the superficial airways have significant mast cell activation and this may lead to the differing symptom presentation compared to asthma.[1][3] Inflammation caused by eosinophils is associated with an increased cough reflex. In another study, however, some follow-up patients who were asymptomatic also had increased eosinophils in their sputum, indicating that the inflammation is not always associated with an increased cough reflex.[1]

The cause of the inflammation can be associated with environmental triggers or common allergens such as dust, chloramine, latex, or welding fumes.[4][7]

Diagnosis[]

Diagnosis of eosinophilic bronchitis is not common as it requires the examination of the patient's sputum for a definitive diagnosis, which can be difficult in those who present with a dry cough. In order to induce the sputum, the patient has to inhale increasing concentrations of hypertonic saline solution.[3][6] If this is unavailable, a bronchoalveolar lavage can be done, and the bronchial wash fluid can be examined for eosinophils.[3] The diagnosis is usually considered later by ruling out other life-threatening conditions or more common diagnoses such as asthma and GERD, and by seeing an improvement in symptoms with inhaled corticosteroid treatment.[2][3][6][8][9] Chest X-rays and lung function tests are usually normal. CT scans may show some diffuse airway wall thickening.[10]

Management[]

If the patient has a known allergen or trigger for the eosinophilic bronchitis, the recommended treatment is to avoid the triggers. If the cause of the eosinophilic bronchitis is unknown, the first line treatment is inhaled corticosteroids.[3][9][11] Patients respond well to inhaled corticosteroids and their eosinophil counts in their sputum usually decrease after treatment.[1][5]

There has not been a study to determine the ideal dosage of inhaled corticosteroids for patients with eosinophilic bronchitis, and there is no consensus on whether the treatment should be discontinued once the patient's symptoms resolve or to continue long-term.[1] The use of oral corticosteroids for eosinophilic bronchitis is rare, but it may be considered when inhaled corticosteroids are ineffective in managing the symptoms.[1][5]

Epidemiology[]

Approximately 10–30% of people who present with a chronic cough are suspected to be symptomatic due to eosinophilic bronchitis.[4][11]

References[]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Gonlugur U, Gonlugur TE (2008). "Eosinophilic bronchitis without asthma". International Archives of Allergy and Immunology. 147 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1159/000128580. PMID 18446047.

- ^ a b c d e Gibson PG, Fujimura M, Niimi A (February 2002). "Eosinophilic bronchitis: clinical manifestations and implications for treatment". Thorax. 57 (2): 178–82. doi:10.1136/thorax.57.2.178. PMC 1746245. PMID 11828051.

- ^ a b c d e f Brightling CE (January 2006). "Chronic cough due to nonasthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines". Chest. 129 (1 Suppl): 116S–121S. doi:10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.116s. PMID 16428700.

- ^ a b c Lai K, Chen R, Peng W, Zhan W (December 2017). "Non-asthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis and its relationship with asthma". Pulmonary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 47: 66–71. doi:10.1016/j.pupt.2017.07.002. PMID 28687463.

- ^ a b c Sakae TM, Maurici R, Trevisol DJ, Pizzichini MM, Pizzichini E (October 2014). "Effects of prednisone on eosinophilic bronchitis in asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia. 40 (5): 552–63. doi:10.1590/S1806-37132014000500012. PMC 4263337. PMID 25410844.

- ^ a b c Achilleos A (September 2016). "Evidence-based Evaluation and Management of Chronic Cough". The Medical Clinics of North America. 100 (5): 1033–45. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2016.04.008. PMID 27542423.

- ^ Yıldız T, Dülger S (January 2018). "Non-astmatic Eosinophilic Bronchitis". Turkish Thoracic Journal. 19 (1): 41–45. doi:10.5152/turkthoracj.2017.17017. PMC 5783052. PMID 29404185.

- ^ Irwin RS, French CL, Chang AB, Altman KW (January 2018). "Classification of Cough as a Symptom in Adults and Management Algorithms: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report". Chest. 153 (1): 196–209. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2017.10.016. PMID 29080708.

- ^ a b Johnstone KJ, Chang AB, Fong KM, Bowman RV, Yang IA (March 2013). "Inhaled corticosteroids for subacute and chronic cough in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD009305. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009305.pub2. PMID 23543575.

- ^ Bernheim A, McLoud T (May 2017). "A Review of Clinical and Imaging Findings in Eosinophilic Lung Diseases". American Journal of Roentgenology. 208 (5): 1002–1010. doi:10.2214/ajr.16.17315. PMID 28225641.

- ^ a b Gahbauer M, Keane P (August 2009). "Chronic cough: Stepwise application in primary care practice of the ACCP guidelines for diagnosis and management of cough". Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 21 (8): 409–16. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2009.00432.x. PMID 19689436.

- Bronchus disorders