Equity (economics)

|

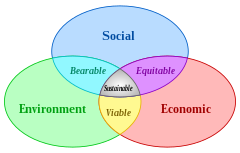

| Scheme of sustainable development: at the confluence of three constituent parts. (2006) |

Equity, or economic equality, is the concept or idea of fairness in economics, particularly in regard to taxation or welfare economics. More specifically, it may refer to equal life chances regardless of identity, to provide all citizens with a basic and equal minimum of income, goods, and services or to increase funds and commitment for redistribution.[1]

Overview[]

There are three distinct categories of substantive fairness (equality, equity, and reciprocity) that must be combined and balanced in order to achieve a truly fair society. [2] Inequality and inequities have significantly increased in recent decades, possibly driven by the worldwide economic processes of globalisation, economic liberalisation and integration.[3] This has led to states 'lagging behind' on headline goals such as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and different levels of inequity between states have been argued to have played a role in the impact of the global economic crisis of 2008–2009.[3]

Equity is based on the idea of moral equality.[3] Equity looks at the distribution of capital, goods, and access to services throughout an economy and is often measured using tools such as the Gini index. Equity may be distinguished from economic efficiency in overall evaluation of social welfare. Although 'equity' has broader uses, it may be posed as a counterpart to economic inequality in yielding a "good" distribution of wealth. It has been studied in experimental economics as inequity aversion.

Taxation[]

In public finance, horizontal equity is the idea that people with a similar ability to pay taxes should pay the same or similar amounts. It is related to the concept of tax neutrality or the idea that the tax system should not discriminate between similar things or people, or unduly distort behavior.[4]

Vertical equity usually refers to the idea that people with a greater ability to pay taxes should pay more. If the rich pay more in proportion to their income, this is known as a proportional tax; if they pay an increasing proportion, this is termed a progressive tax, sometimes associated with redistribution of wealth.[5]

Health care[]

Horizontal equity means providing equal health care to those who are the same in a relevant respect (such as having the same 'need'). Vertical equity means treating differently those who are different in relevant respects (such as having different 'need'), (Culyer, 1995).

Health studies of equity whether particular social groups receive systematically different levels of care than do other groups. There are many ways to identify preventable or unjust disparities, including the study of health outcomes using quintile analysis or concentration indexes.

Fair division[]

Equitability in fair division means every person’s subjective valuation of their own share of some goods is the same. The surplus procedure (SP) achieves a more complex variant called proportional equitability. For more than two people, a division cannot always both be equitable and envy-free.[6]

See also[]

- Equity (law)

- Educational equity

- Distributive justice

- Excess burden of taxation

- Justice (economics)

- Progressive tax

- Proportional tax

- "Redistributive justice"

- Tax incidence

- Who Moved My Cheese

Notes[]

- ^ Kate Bird 2009. Building a fair future: why equity matters Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine. London: Overseas Development Institute

- ^ https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-fair-society/201107/is-capitalism-fair

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Blaze Bolenbaugh 2009. Equity in development: Why it is important and how to achieve it. London: Overseas Development Institute

- ^ Musgrave (1987), pp. 1057–58.

- ^ Musgrave (1959), p. 20.

- ^ Better Ways to Cut a Cake by Steven J. Brams, Michael A. Jones, and Christian Klamler in the Notices of the American Mathematical Society December 2006.

References[]

- Anthony B. Atkinson and Joseph E. Stiglitz (1980). Lectures in Public Economics, McGraw-Hill. Economics Handbook Series.

- Xavier Calsamiglia and Alan Kirman (1993). "A Unique Informationally Efficient and Decentralized Mechanism with Fair Outcomes," Econometrica, 61(5), p p. 1147-1172.

- A.J. Culyer (1995). "Need: The Idea Won't Do — But We Still Need It," Social Science and Medicine, 40(6), pp. 727–730.

- Jean-Yves Duclos (2008). "horizontal and vertical equity," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition. Abstract.

- Allan M. Feldman (1987). "equity," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 2, pp. 182–84.

- Peter J. Hammond (1987). "altruism," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 1, pp. 85–87.

- Serge-Christophe Kolm ([1972] 2000). Justice and Equity. Description & chapter-preview links. MIT Press.

- Julian Le Grand (1991). Equity and Choice: An Essay in Economics and Applied Philosophy. Chapter preview links.

- Richard A. Musgrave (1959). The Theory of Public Finance: A Study in Political Economy.

- _____ (1987 [2008]). "public finance," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 3, pp. 1055–60. Abstract.

- Richard A. Musgrave and Peggy B. Musgrave (1973). Public Finance in Theory and Practice

- Joseph E. Stiglitz (2000). Economics of the Public Sector, 3rd ed. Norton.

- William Thomson (2008). "fair allocation," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition. Abstract.

- World Bank. World Development Report 2006: Equity and Development.Summary with ch. links.

- H. Peyton Young (1994). Equity: In Theory and Practice. Princeton University Press. Description, preview, and chapter 1[permanent dead link].

- Colombino, U., Locatelli, M., Narazani, E., & O'Donoghue, C. (2010). Alternative basic income mechanisms: An evaluation exercise with a microeconometric model. Basic Income Studies, 5(1).

- Fairness criteria

- Tax incidence

- Welfare economics