Ernie Anderson

Ernie Anderson | |

|---|---|

Ernie Anderson c. 1961 | |

| Born | Ernest Earle Anderson November 12, 1923 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | February 6, 1997 (aged 73) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Hollywood Hills) |

| Occupation | Actor, television personality, announcer, horror host, disc jockey |

| Years active | 1946–1997 |

| Known for | Ghoulardi The voice of the American Broadcasting Company |

| Spouse(s) | Marguerite Hemmer

(m. 1947; div. 1966)Edwina Gough

(m. 1968; div. 1995)Bonnie Skolnick

(m. 1996) |

| Children | 9, including Paul |

Ernest Earle Anderson (November 12, 1923 – February 6, 1997) was an American radio and television personality, horror host, and announcer.

Known for his portrayal of "Ghoulardi," the host of a late night horror films on WJW Channel 8 on Cleveland television from 1963 to 1966,[1] he worked as an announcer for the American Broadcasting Company (ABC) television network from the late 1970s until the mid-1990s.

He is the father of filmmaker Paul Thomas Anderson, whose production entity is known as the Ghoulardi Film Company.

Early life and career[]

Anderson was born in Boston and grew up in Lynn, Massachusetts,[2] the son of Emily (Malenson) and Ernest C. Anderson. Anderson planned to go to law school, but instead joined the U.S. Navy during World War II to avoid being drafted.[2] In an interview, his son Paul Thomas Anderson spoke of his military service:

He (Ernie) was in the Navy stationed mainly in Guam. I don't think he did any fighting. I think he was trying - he was fixing airplanes and knew just where the beer was stashed and played the saxophone in bands and stuff like that. You know, every picture I have of him [shows] a beer in his hand. Every single picture from the war he's got - so he was pretty good about probably finding ways to get out of fighting. But again, you know, we never really talked that much about it.[3]

After the war, Anderson attended Suffolk University for two years, then took a job as a disc jockey at WSKI in Montpelier, Vermont.[4][5] Anderson worked as a disc jockey in Albany, New York and Providence, Rhode Island before moving to Cleveland, Ohio in 1958 to join radio station WHK.[4][6]

After WHK switched to a Top 40 format in late 1958, Anderson was let go as his persona did not fit with the format's newer, high-energy presentation. According to Anderson's lifelong friend, comic actor Tim Conway, Anderson was at a WHK Christmas party "telling this long elaborate joke and just as he's about to deliver the punch line his boss cuts in and says it. So Ernie looks at him and says, 'Why did you do that?' And his boss says, 'I anticipated it.' So Ernie said, 'Anticipate this' and tells him '(expletive) yourself.' Well, Ernie got fired."[7]

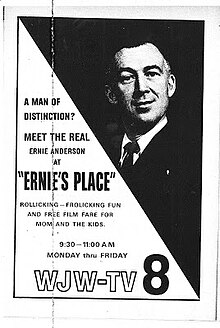

Anderson switched to television, joining the Cleveland NBC affiliate KYW-TV (now WKYC), where he first collaborated with Conway for some on-air work. In mid-1961, both Anderson and Conway moved to then-CBS affiliate WJW-TV to host a local morning movie show called Ernie's Place, which also featured live skits and comedy bits reminiscent of Bob and Ray. When the two men joined the station, Anderson sold Conway to WJW's management team as a director for the program, even though Conway lacked qualifications and experience for that position. Conway proved unable to do the work, and other staffers, including technician Chuck Schodowski, were called in to assist, before Conway was ultimately dismissed. With Anderson deprived of his comic foil, Ernie's Place was canceled, but management soon offered him a horror host role for a local incarnation of Shock Theater that WJW acquired the rights to air late-nights on Fridays.

"Ghoulardi" years[]

From 1963 to 1966, Anderson hosted Shock Theater under the alter ego of Ghoulardi, a hipster that defied the common perception of a horror host. While this version of Shock Theater also featured grade "B" science fiction and horror films, Ghoulardi mocked the films he was hosting, and spoke in an accent-laden beatnik slang. Often, comedic sound effects or music would be inserted in place of the movie's audio track. Occasionally, Ghoulardi would even insert himself into a film and appear to run from the monster, using a chroma key system that WJW normally utilized for art cards. He loved firecrackers (although their possession was illegal in Ohio) and started by blowing up apples and leftovers and graduated to blowing up model cars, statues and other items sent in by viewers.

One remnant of Ernie's Place was also revived: the live comedy sketches and skits, only with Chuck Schodowski assuming Conway's role as Anderson's primary sidekick. On occasion, Conway would make cameo appearances on the program and serve as a writer, but Conway had meanwhile become a nationally known star on ABC's comedy series McHale's Navy.

Anderson's "Ghoulardi" persona often lampooned "unhip" targets, Dorothy Fuldheim being one of them. Fuldheim was the first woman to anchor a TV news show in the United States, and a lifelong staffer for Cleveland's ABC affiliate WEWS. She openly expressed a dislike for Anderson, feeling that the youth of Ohio were under attack with his pot jokes and childish antics, which she found distasteful. Ghoulardi responded by mocking her every week, usually referring to her as "Dorothy Baby." Their mutual on-air jibes created what viewers considered a battle of "the beatnik and the empress of Ohio news."

Anderson also developed "Parma Place", a weekly series of skits aired during the Ghoulardi show that parodied both the popular prime-time soap opera Peyton Place and the bedroom community of Parma, Ohio. "Parma Place" became an instant hit among the viewers, but its heavy use of ethnic jokes and asides toward Parma eventually caused that city's elected officials to complain to WJW management. While the station acquiesced and ordered the cancellation of "Parma Place", the publicity from that incident and the Fuldheim feud put the Ghoulardi character at the peak of his popularity.

By 1965, Anderson not only hosted Shock Theater but also the Saturday afternoon Masterpiece Theater and the weekday children's program Laurel, Ghoulardi and Hardy, all of which were ratings successes. Anderson also created the "Ghoulardi All-Stars" sports teams, which would often attract thousands of fans to as many as 100 charity contests a year. With some help from Conway, Anderson even visited Hollywood to shoot a TV pilot, and featured the audition and films of his trip on his show, highly unusual for local TV in 1966.

Promises of becoming an actor in Los Angeles, as well as fatigue on Anderson's part, led up to his decision to leave Cleveland permanently in the summer of 1966. Shock Theater ended in October 1966, and the Ghoulardi name was retired. WJW tapped both Schodowski and weather presenter Bob Wells (aka "Hoolihan the Weatherman") to co-host the successive program, Hoolihan and Big Chuck.

Move to Los Angeles and career at the American Broadcasting Company[]

After moving to Los Angeles, Anderson first appeared on the first two episodes of Rango, a short-lived comedy that starred Conway. Anderson and Conway soon collaborated on a comedy act, appearing together on ABC's Hollywood Palace and later releasing two comedy albums together.[8] Beginning in 1974, Anderson replaced Lyle Waggoner as announcer for The Carol Burnett Show, on which his old performing partner Conway (who had been a recurring guest on the show) became a regular performer beginning in the following year.

Anderson found it a challenge to land acting work. His son, Paul Thomas Anderson, also attributes this to his father's profound limitations as an actor: "He was a bad actor, so he never really made it....No, he was bad. When we used to make home movies, he'd be in them and he was bad. We'd be like: 'You fucker. No wonder you couldn't get any jobs."[9]

Anderson admittedly had lifelong difficulty with memorization. He moved behind the microphone when Fred Silverman made Anderson the voice of the American Broadcasting Company. His voice was heard in the ABC bumpers during the 1970s and 1980s saying "This is... ABC!" Anderson's voice is likely best remembered for introducing and promoting the ABC television series The Love Boat and for his newscast introductions for various ABC stations across the country: "Eyewitness News...starts...NOW!" (WEWS in Cleveland, the employer of Dorothy Fuldheim, would be one of these affiliates, utilizing Anderson's voice throughout the 1980s.) Anderson was also the announcer of America's Funniest Home Videos from 1989 to 1995, and did the voiceover for the previews of new episodes during the first three seasons of Star Trek: The Next Generation until he was replaced by Don LaFontaine. In addition to his work for ABC, Anderson also did commercial work for Ford, RCA and other clients.[4]

Anderson's signature was putting emphasis on a particular word. Examples included his enunciation of "Love" when saying "The Love Boat", and "The Man... The Machine... Street Hawk!" from the 1985 motorcycle action series. Anderson told the San Francisco Chronicle that his goal as an announcer was to "try to create a mood. I have to concentrate on each word, on each syllable. I have to bring something special to every sentence I say. If I don't do that, they might as well just get some announcer out of the booth to read it. I want people to hear me talk about a show and then to say, 'Hey, this is going to be great. I want to watch this.'"[10]

Voiceovers in animation[]

Anderson also lent his narration voice to animated television series. He narrated the opening intros to Jayce and the Wheeled Warriors and The Adventures of Super Mario Bros. 3 (all for DIC Entertainment) and narrated the first two television shorts of The Powerpuff Girls as part of The What-a-Cartoon! Show until his death in 1997, when the role was taken over by Tom Kenny.

Personal life and death[]

Despite being a daily presence on American television, Anderson lived in relative anonymity in Southern California. "But that's all right," he said. "If I'm out in public and I feel like being recognized, I just raise my voice and say... 'The Love Boat.'"[11]

Anderson had nine children in total. He had five children with his first wife, Marguerite Hemmer, whom he divorced around the time he ended his Ghoulardi show and left Cleveland. The three older children relocated to live with him in Studio City, while the two youngest children lived in Rhode Island with their mother.

Anderson married actress Edwina Gough soon after she arrived in California, a few weeks after he did so. With Edwina, he had three daughters and one son, filmmaker Paul Thomas Anderson. They divorced in the mid-1990s. Ernie then married Bonnie Skolnick, who survived him for a very short time.[4]

A lifelong smoker, Anderson died of lung cancer on February 6, 1997[12] and is buried in Hollywood Hills, Los Angeles.[13] His son, director Paul Thomas Anderson, dedicated his 1997 film Boogie Nights to his memory. In addition, The Drew Carey Show episode "See Drew Run" was dedicated to his memory. His death was also mentioned on an episode of America's Funniest Home Videos that same year.

Influence and legacy[]

Among others he influenced, Anderson influenced the film work of his son Paul Thomas Anderson and of the director Jim Jarmusch. In Paul Thomas Anderson's third film Magnolia, Earl Partridge is dying of cancer like Ernie Anderson.[14] Paul Thomas Anderson has also confirmed that the climactic scene of his film Boogie Nights involving fireworks was inspired by his father's use of fireworks on the Ghoulardi program.[15] Jarmusch, who watched Ghoulardi as a child living in the Cleveland area, has stated that he was greatly influenced by the character's "anti-hierarchical appreciation of culture" and selection of "weird" background music.[16]

Anderson as "Ghoulardi" has also been cited as an early influence on many Cleveland and Akron-area musicians who formed influential rock and punk bands in the 1970s, including Devo, The Dead Boys, Pere Ubu, and The Cramps.[16][17]

More than a decade after his death, radio stations could still license Anderson's voice for promotions.[18] By paying a licensing fee, stations including New York City's WHTZ used Anderson's voice for positioning statements such as, "If it's too loud, you're too old" and "Lock it in and rip the knob off!"[19]

References[]

- ^ "Cleveland legend Ghoulardi casts long shadow decades later". cleveland.com. October 26, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hoffman, Phil, producer/director (2009). Turn Blue: The Short Life of Ghoulardi (Motion picture documentary). Roc Doc Productions/ Western Reserve Public Media. Retrieved 2015-10-04.

- ^ Anderson, Paul Thomas (2012-10-02). "The Fresh Air Interview: Paul Thomas Anderson, The Man Behind 'The Master'". Fresh Air (Interview). Interviewed by Terry Gross. Cordova, Tennessee: WKNO. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-03-05.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Anderson, Ernie". Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. Case Western Reserve University. 2010-10-05. Archived from the original on January 16, 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-03.

- ^ Starr Seibel, Deborah (1991-10-24). "Deep Words From The Voice Of America - TV's Most Sought-After Announcer Puts His Mouth Where The Money - Is". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Cobb, Nathan (1985-04-09). "He Uses His Voice To Entice You: Ernie Anderson Is Prime-Time Pitchman For ABC-TV's Programs". The Boston Globe.

- ^ Petkovic, John (2013-01-12). "Ghoulardi at 50: Tim Conway, Jim Jarmusch, Paul Thomas Anderson pay tribute to Cleveland icon". The Plain Dealer. Cleveland, Ohio. Archived from the original on 2015-10-05. Retrieved 2016-03-05.

- ^ Feran, Tom (1997-02-07). "TV Icon 'Ghoulardi' Dies at 73". The Plain Dealer.

- ^ "'I can be a real arrogant brat'". The Guardian. 2003-01-27. Retrieved 2021-01-17.

- ^ Greene, Bob (1985-06-04). "Televisions' Most Recognizable Voice". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Greene, Bob (1985-02-24). "The Man Behind the Voice of ABC". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Feran, Tom (1997-02-07). "TV Icon 'Ghoulardi' Dies at 73". The Plain Dealer.

- ^ Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Locations 1153-1154). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Rossio, Jordan (2013-12-06). God Only Knows: Family in the Films of Paul Thomas Anderson (Honors thesis). Western Michigan University. Archived from the original on October 4, 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-03.

- ^ Konow, David (2014-12-11). "How Paul Thomas Anderson Was Influenced By His Irreverent Dad". Esquire. United States: Hearst Corporation. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-03.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Petkovic, John (2013-01-12). "Cleveland's Ghoulardi Went On the Air 50 Years Ago and Cast His Spell Over the City". The Plain Dealer. Retrieved 2015-10-03.

- ^ Urycki, Mark (2013-12-21). "50 Years Later, TV's Ghoulardi Lives — In Punk Rock". NPR. Retrieved 2015-10-03.

- ^ Feran, Tom (2000-03-01). "High Tech Lets 'Ghoulardi' Speak From The Grave". The Plain Dealer.

- ^ Gallagher, David F. (2004-02-02). "Compressed Data - Legendary Voice for Hire. No Live Gigs". The New York Times.

Further reading[]

- Feran, Tom; Heldenfels, Rich (1999) Ghoulardi: Inside Cleveland TV's Wildest Ride. Cleveland, OH: Gray & Company, Publishers. ISBN 978-1-886228-18-4

- Schodowski, Chuck (2008). Big Chuck: My Favorite Stories from 47 Years on Cleveland TV. Cleveland, OH: Gray & Company, Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59851-052-2

External links[]

- 1923 births

- 1997 deaths

- 20th-century American male actors

- Actors from Lynn, Massachusetts

- American male television actors

- American male voice actors

- Burials at Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Hollywood Hills)

- Deaths from cancer in California

- Game show announcers

- Horror hosts

- Male actors from Cleveland

- Male actors from Los Angeles

- Radio and television announcers

- Radio personalities from Cleveland

- Radio personalities from Los Angeles

- Radio personalities from Massachusetts

- Suffolk University alumni

- Television in Cleveland

- Deaths from cancer of unknown primary origin

- United States Navy personnel of World War II