Essays (Francis Bacon)

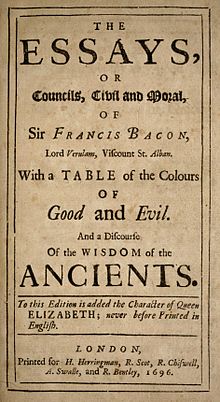

Essayes: Religious Meditations. Places of Perswasion and Disswasion. Seene and Allowed (1597) was the first published book by the philosopher, statesman and jurist Francis Bacon. The Essays are written in a wide range of styles, from the plain and unadorned to the epigrammatic. They cover topics drawn from both public and private life, and in each case the essays cover their topics systematically from a number of different angles, weighing one argument against another. While the original edition included 10 essays, a much-enlarged second edition appeared in 1612 with 38. Another, under the title Essayes or Counsels, Civill and Morall, was published in 1625 with 58 essays. Translations into French and Italian appeared during Bacon's lifetime.[1][2] In Bacon's Essay, "Of Plantations" published in 1625, he relates planting colonies to war. He states that such plantations should be governed by those with a commission or authority to exercise martial law.[3]

Critical reception[]

Though Bacon considered the Essays "but as recreation of my other studies", he was given high praise by his contemporaries, even to the point of crediting him with having invented the essay form.[4][5] Later researches made clear the extent of Bacon's borrowings from the works of Montaigne, Aristotle and other writers, but the Essays have nevertheless remained in the highest repute.[6][7] The 19th-century literary historian Henry Hallam wrote that "They are deeper and more discriminating than any earlier, or almost any later, work in the English language".[8]

The Essays stimulated Richard Whately to republish them with annotations, somewhat extensive, that Whately extrapolated from the originals.[9]

Aphorisms[]

Bacon's genius as a phrase-maker appears to great advantage in the later essays. In Of Boldness he wrote, "If the Hill will not come to Mahomet, Mahomet will go to the hill", which is the earliest known appearance of that proverb in print.[10] The phrase "hostages to fortune" appears in the essay Of Marriage and Single Life – again the earliest known usage.[11] Aldous Huxley's book Jesting Pilate took its epigraph, "What is Truth? said jesting Pilate; and would not stay for an answer", from Bacon's essay Of Truth.[12] The 1999 edition of The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations includes no fewer than 91 quotations from the Essays.[13]

Contents listing[]

The contents pages of Thomas Markby's 1853 edition list the essays and their dates of publication as follows:[14]

- Of Truth (1625)

- Of Death (1612, enlarged 1625)

- Of Unity in Religion/Of Religion (1612, rewritten 1625)

- Of Revenge (1625)

- Of Adversity (1625)

- Of Simulation and Dissimulation (1625)

- Of Parents and Children (1612, enlarged 1625)

- Of Marriage and Single Life (1612, slightly enlarged 1625)

- Of Envy (1625)

- Of Love (1612, rewritten 1625)

- Of Great Place (1612, slightly enlarged 1625)

- Of Boldness (1625)

- Of Goodness and Goodness of Nature (1612, enlarged 1625)

- Of Nobility (1612, rewritten 1625)

- Of Seditions and Troubles (1625)

- Of Atheism (1612, slightly enlarged 1625)

- Of Superstition (1612, slightly enlarged 1625)

- Of Travel (1625)

- Of Empire (1612, much enlarged 1625)

- Of Counsels (1612, enlarged 1625)

- Of Delays (1625)

- Of Cunning (1612, rewritten 1625)

- Of Wisdom for a Man's Self (1612, enlarged 1625)

- Of Innovations (1625)

- Of Dispatch (1612)

- Of Seeming Wise (1612)

- Of Friendship (1612, rewritten 1625)

- Of Expense (1597, enlarged 1612, again 1625)

- Of the True Greatness of Kingdoms and Estates (1612, enlarged 1625)

- Of Regiment of Health (1597, enlarged 1612, again 1625)

- Of Suspicion (1625)

- Of Discourse (1597, slightly enlarged 1612, again 1625)

- Of Plantations (1625)

- Of Riches (1612, much enlarged 1625)

- Of Prophecies (1625)

- Of Ambition (1612, enlarged 1625)

- Of Masques and Triumphs (1625)

- Of Nature in Men (1612, enlarged 1625)

- Of Custom and Education (1612, enlarged 1625)

- Of Fortune (1612, slightly enlarged 1625)

- Of Usury (1625)

- Of Youth and Age (1612, slightly enlarged 1625)

- Of Beauty (1612, slightly enlarged 1625)

- Of Deformity (1612, somewhat altered 1625)

- Of Building (1625)

- Of Gardens (1625)

- Of Negotiating (1597, enlarged 1612, very slightly altered 1625)

- Of Followers and Friends (1597, slightly enlarged 1625)

- Of Suitors (1597, enlarged 1625)

- Of Studies (1597, enlarged 1625)

- In “Of Studies” Bacon discusses how studies can assist us in different ways. He begins the essay with the three ways through which studies serve the readers: delight, ornament, and ability. Studies delight the reader. We can also use studies as an ornament in communication. Moreover, studies improve the ability of the reader. However, Bacon does not ask the reader for excessive reading. He says that excessive reading makes the reader lazy. Even using too much knowledge in discourse will be pretentious. Making a judgment based on the books will be also hilarious. Therefore, a balance is needed. We cannot deny the importance of books. However, shrewd men don’t like studies. On the other hand, simple men admire them. But wise men apply the knowledge of books in real life. Wise men can take the nectar of books that contain the wisdom of various people. Bacon also tells the reader not to read books to contradict, nor to believe in what is the book, nor to use the book as a tool in discourse, rather, one should read a book to evaluate its importance. Furthermore, Bacon says some books are to be read-only in parts. We can do this to extract some basic information about a book. Some others need to be read without any curiosity. We read it to imbibe factual information, and but some few books need mental exercise for proper understanding. While reading such books, one needs attention and diligence. Bacon again comes back to the importance of reading books and says that studies make a man complete because the reader’s mind is filled with knowledge from various men. Similarly, discussion improves the ability of a man to talk on any topic because of his practice of discussion. Lastly, if a man practices writing, it makes him an exact man because there is no chance of forgetting. Therefore, Bacon says that if a man writes little, he needs to have great memory so that he does not forget things. Similarly, if a man does not have the habit of engaging in a discussion, he needs to have a present state of mind to tackle any situation in his public life. Lastly, if a man does not read, then he needs to pretend that he possesses knowledge. Along with the benefits of reading books, Bacon says, “Histories make men wise; poets witty; the mathematics subtile; natural philosophy deep; moral, grave; logic and rhetoric, able to contend.” He also says that reading can cure every problem related to the intellect. Bacon says for every disease of the body, we have particular exercise to cure the disease. Similarly, for every problem of the mind, we have a particular solution. For instance, if the mind is distracted a lot, then mathematics can help in improving focus. If the mind finds it difficult to distinguish or find differences between mater studying philosophers and theologians of the Middle Ages will be helpful. Lastly, to improve reasoning skills, reading lawyer’s cases will be helpful.[15]

- Of Faction (1597, much enlarged 1625)

- Of Ceremonies and Respects (1597, enlarged 1625)

- Of Praise (1612, enlarged 1625)

- Of Vain Glory (1612)

- Of Honour and Reputation (1597, omitted 1612, republished 1625)

- Of Judicature (1612)

- Of Anger (1625)

- Of Vicissitude of Things (1625)

- A Fragment of an Essay of Fame

- Of the Colours of Good and Evil

Recent editions[]

- Michael J. Hawkins (ed.) Essays (London: J. M. Dent, 1973). No. 1010 in Everyman's Library.

- Michael Kiernan (ed.) The Essayes or Counsels, Civill and Morall (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985). Vol. 15 of The Oxford Francis Bacon.

- John Pitcher (ed.) The Essays (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985). In the Penguin Classics series.

- Brian Vickers (ed.) The Essays or Counsels, Civil and Moral (New York: Oxford University Press). In the Oxford World's Classics series.

See also[]

Footnotes[]

- ^ Burch, Dinah (ed). "The Essays". The Oxford Companion to English Literature. Oxford Reference Online (Subscription service). Retrieved 12 May 2012.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ "Catalogue entry". Copac. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ Zeitlin, Samuel Garrett (2021). "Francis Bacon on Imperial and Colonial Warfare". The Review of Politics. 83 (2): 196–218. doi:10.1017/S0034670520001011. ISSN 0034-6705.

- ^ Heard, Franklin Fiske. "Bacon's Essays, with annotations by Richard Whately and notes and a glossarial index". Making of America Books. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- ^ Bacon, Francis (2000) [1985]. Kiernan, Michael (ed.). The Essayes or Counsels, Civill and Morall. New York: Oxford University Press. p. xlix. ISBN 0198186738. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- ^ Matthew, H. C. G.; Harrison, Brian, eds. (2004). The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, vol. 3. Oxford University Press. p. 142.

- ^ Ward, A. W.; Waller, A. R., eds. (1907–27). The Cambridge History of English and American Literature. Cambridge University Press. pp. 395–98.

- ^ Hallam, Henry (1854). Introduction to the Literature of Europe in the Fifteenth, Sixteenth, and Seventeenth Centuries, Vol 2. Boston: Little, Brown. p. 514.

- ^ Richard Whately (1858) Bacon’s Essays with Annotations via Internet Archive

- ^ Simpson, John (1993). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Proverbs. Oxford University Press. p. 176.

- ^ The Oxford English Dictionary Vol 7. Oxford. 1989. p. 418.

- ^ Huxley, Aldous (1930). Jesting Pilate. London: Chatto and Windus.

- ^ Knowles, Elizabeth M., ed. (1999). The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations. Oxford University Press. pp. 42–44.

- ^ Markby, Thomas (1853). The Essays, or, Counsels, Civil and Moral; With a Table of the Colours of Good and Evil. London: Parker. pp. xi–xii. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- ^ Seeker, The Solitude (15 April 2020). "Of Studies by Francis Bacon". Literary Yog. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

External links[]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- 16th-century books

- 17th-century books

- 1597 books

- British essays

- Essay collections

- Modern philosophical literature

- Philosophy essays

- Works by Francis Bacon (philosopher)