Etruscan religion

Etruscan religion comprises a set of stories, beliefs, and religious practices of the Etruscan civilization, heavily influenced by the mythology of ancient Greece, and sharing similarities with concurrent Roman mythology and religion. As the Etruscan civilization was gradually assimilated into the Roman Republic from the 4th century BC, the Etruscan religion and mythology were partially incorporated into ancient Roman culture, following the Roman tendency to absorb some of the local gods and customs of conquered lands. The first attestations of an etruscan religion belong to the villanovan phase.[1]

History[]

Greek influence[]

Greek traders brought their religion and hero figures with them to the coastal areas of the central Mediterranean. Odysseus, Menelaus and Diomedes from the Homeric tradition were recast in tales of the distant past that had them roaming the lands West of Greece. In Greek tradition, Heracles wandered these western areas, doing away with monsters and brigands, and bringing civilization to the inhabitants. Legends of his prowess with women became the source of tales about his many offspring conceived with prominent local women, though his role as a wanderer meant that Heracles moved on after securing the locations chosen to be settled by his followers, rather than fulfilling a typical founder role. Over time, Odysseus also assumed a similar role for the Etruscans as the heroic leader who led the Etruscans to settle the lands they inhabited.[2]

Claims that the sons of Odysseus had once ruled over the Etruscan people date to at least the mid-6th century BC. Lycophron and Theopompus link Odysseus to Cortona (where he was called Nanos).[3][4] In Italy during this era it could give non-Greek ethnic groups an advantage over rival ethnic groups to link their origins to a Greek hero figure. These legendary heroic figures became instrumental in establishing the legitimacy of Greek claims to the newly settled lands, depicting the Greek presence there as reaching back into antiquity.[2]

Roman conquest[]

After the Etruscan defeat in the Roman–Etruscan Wars, the remaining Etruscan culture began to be assimilated into the Roman. The Roman Senate adopted key elements of the Etruscan religion, which were perpetuated by haruspices and noble Roman families who claimed Etruscan descent, long after the general population of Etruria had forgotten the language. In the last years of the Roman Republic the religion began to fall out of favor and was satirized by such notable public figures as Marcus Tullius Cicero. The Julio-Claudians, especially Claudius, who claimed a remote Etruscan descent, maintained a knowledge of the language and religion for a short time longer,[5] but this practice soon ceased. A number of canonical works in the Etruscan language survived until the middle of the first millennium AD, but were destroyed by the ravages of time, including occasional catastrophic fires, and by decree of the Roman Senate.[citation needed]

Sources[]

The mythology is evidenced by a number of sources in different media, for example representations on large numbers of pottery, inscriptions and engraved scenes on the Praenestine cistae (ornate boxes; see under Etruscan language) and on specula (ornate hand mirrors). Currently some two dozen fascicles of the Corpus Speculorum Etruscorum have been published. Specifically Etruscan mythological and cult figures appear in the Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae.[6] Etruscan inscriptions have recently been given a more authoritative presentation by Helmut Rix, Etruskische Texte.[7]

Seers and divinations[]

The Etruscans believed their religion had been revealed to them by seers,[8] the two main ones being Tages, a childlike figure born from tilled land who was immediately gifted with prescience, and Vegoia, a female figure.

The Etruscans believed in intimate contact with divinity.[9] They did nothing without proper consultation with the gods and signs from them.[10] These practices were taken over in total by the Romans.

Etrusca Disciplina[]

The Etruscan scriptures were a corpus of texts termed the Etrusca Disciplina. This name appears in Valerius Maximus,[11] and Marcus Tullius Cicero refers to a disciplina in his writings on the subject.

Massimo Pallottino summarizes the known (but non-extant) scriptures as the Libri Haruspicini, containing the theory and rules of divination from animal entrails; the Libri Fulgurales, describing divination from lightning strikes; and the Libri Rituales. The last was composed of the Libri Fatales, detailing the religiously correct methods of founding cities and shrines, draining fields, formulating laws and ordinances, measuring space and dividing time; the Libri Acherontici, dealing with the hereafter; and the Libri Ostentaria, containing rules for interpreting prodigies. The revelations of the prophet Tages were given in the Libri Tagetici, which included the Libri Haruspicini and the Acherontici, and those of the prophetess Vegoia in the Libri Vegoici, which included the Libri Fulgurales and part of the Libri Rituales.[12]

These works did not present prophecies or scriptures in the ordinary sense: the Etrusca Disciplina foretold nothing itself. The Etruscans appear to have had no systematic ethics or religion and no great visions. Instead they concentrated on the problem of the will of the gods: questioning why, if the gods created the universe and humanity and have a will and a plan for everyone and everything in it, they did not devise a system for communicating that will in a clear manner.[citation needed]

The Etruscans accepted the inscrutability of their gods' wills. They did not attempt to rationalize or explain divine actions or formulate any doctrines of the gods' intentions. As answer to the problem of ascertaining the divine will, they developed an elaborate system of divination; that is, they believed the gods offer a perpetual stream of signs in the phenomena of daily life, which if read rightly can direct humanity's affairs. These revelations may not be otherwise understandable and may not be pleasant or easy, but are perilous to doubt.

The Etrusca Disciplina therefore was mainly a set of rules for the conduct of all sorts of divination; Pallottino calls it a religious and political "constitution": it does not dictate what laws shall be made or how humans are to behave, but rather elaborates rules for asking the gods these questions and receiving answers.

Cicero said[13]

For a hasty acceptance of an erroneous opinion is discreditable in any case, and especially so in an inquiry as to how much weight should be given to auspices, to sacred rites, and to religious observances; for we run the risk of committing a crime against the gods if we disregard them, or of becoming involved in old women's superstition if we approve them.

He then quipped, regarding divination from the singing of frogs:

Who could suppose that frogs had this foresight? And yet they do have by nature some faculty of premonition, clear enough of itself, but too dark for human comprehension.

Priests and officials[]

Divinatory inquiries according to discipline were conducted by priests whom the Romans called haruspices or sacerdotes; Tarquinii had a college of 60 of them.[12] The Etruscans, as evidenced by the inscriptions, used several words: capen (Sabine cupencus), maru (Umbrian maron-), eisnev, hatrencu (priestess). They called the art of haruspicy ziχ neθsrac.

A special magistrate, the cechase, looked after the cecha or rath, sacred things. Every man, however, had his religious responsibilities, which were expressed in an alumnathe or slecaches, a sacred society. No public event was conducted without the netsvis, the haruspex, or his female equivalent, the nethsra, who would read the bumps on the liver of a properly sacrificed sheep. We have a model of a liver made of bronze, whose religious significance is still a matter of heated debate, marked into sections which perhaps are meant to explain what a bump in that region would mean.

Beliefs[]

The Etruscan system of belief was an immanent polytheism; all visible phenomena were considered to be manifestations of divine power, and that power was embodied in deities who acted continually on the world but could be dissuaded or persuaded by mortal men.[citation needed]

Long after the assimilation of the Etruscans, Seneca the Younger said[14] that the difference between the Romans and the Etruscans was that

Whereas we believe lightning to be released as a result of the collision of clouds, they believe that the clouds collide so as to release lightning: for as they attribute all to deity, they are led to believe not that things have a meaning insofar as they occur, but rather that they occur because they must have a meaning.

Spirits and deities[]

After the 5th century, iconographic depictions show the deceased traveling to the underworld.[15] In several instances of Etruscan art, such as in the François Tomb in Vulci, a spirit of the dead is identified by the term hinthial, literally "(one who is) underneath". The souls of the ancestors, called man or mani (Latin Manes), were believed to be found around the mun or muni, or tombs,[citation needed]

A god was called an ais (later eis), which in the plural is aisar. The abode of a god was a fanu or luth, a sacred place, such as a favi, a grave or temple. There, one would need to make a fler (plural flerchva), or "offering".

Three layers of deities are portrayed in Etruscan art. One appears to be divinities of an indigenous origin: Voltumna or Vertumnus, a primordial, chthonic god; Usil, god(-dess) of the sun; , god of the moon; Turan, goddess of love; Laran, god of war; Maris, goddess of (child-)birth; Leinth, goddess of death; Selvans, god of the woods; Nethuns, god of the waters; Thalna, god of trade; Turms, messenger of the gods; Fufluns, god of wine; the heroic figure Hercle; and Catha, whose religious sphere is uncertain.[16]

Ruling over them were higher deities that seem to reflect the Indo-European system: Tin or Tinia, the sky, Uni his wife (Juno), and Cel, the earth goddess.

As a third layer, the Greek gods were adopted by the Etruscan system during the Etruscan Orientalizing Period of 750/700–600 BC.[17] Examples are Aritimi (Artemis), Menrva (Minerva; Latin equivalent of Athena), and Pacha (Bacchus; Latin equivalent of Dionysus), and over time the primary trinity became Tinia, Uni and Menrva. This triad of gods were venerated in Tripartite temples similar to the later Roman Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus[16]

A fourth group, the so-called dii involuti or "veiled gods", are sometimes mentioned as superior to all the other deities, but these were never worshipped, named, or depicted directly.[18]

Afterlife[]

Etruscan beliefs concerning the hereafter appear to be an amalgam of influences. The Etruscans shared general early Mediterranean beliefs, such as the Egyptian belief that survival and prosperity in the hereafter depend on the treatment of the deceased's remains.[19] Etruscan tombs imitated domestic structures and were characterized by spacious chambers, wall paintings and grave furniture. In the tomb, especially on the sarcophagus (examples shown below), was a representation of the deceased in his or her prime, often with a spouse. Not everyone had a sarcophagus; sometimes the deceased was laid out on a stone bench. As the Etruscans practiced mixed inhumation and cremation rites (the proportion depending on the period), cremated ashes and bones might be put into an urn in the shapes of a house or a representation of the deceased.

Funerary home at Banditaccia with couches

Funerary home at Populonia

Sarcophagus from Siena

Sarcophagus from Chiusi

Sarcophagus

Burial urn

Urn from Chiusi

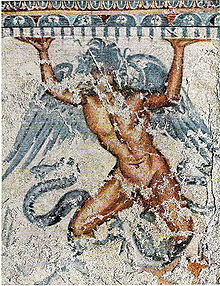

In addition to the world still influenced by terrestrial affairs was a transmigrational world beyond the grave, patterned after the Greek Hades.[citation needed] It was ruled by Aita, and the deceased was guided there by Charun, the equivalent of Death, who was blue and wielded a hammer. The Etruscan Hades was populated by Greek mythological figures and a few such as Tuchulcha, of composite appearance.

See also[]

- Interpretatio graeca

- List of Etruscan mythological figures

- List of Etruscan names for Greek heroes

Notes[]

- ^ Thomson de Grummond, Nancy; Simon, Erika (2006). The Religion of the Etruscans. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-70687-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Miles, Richard (21 July 2011). Carthage Must Be Destroyed. United Kingdom.

- ^ Etruscology. 1. Germany. 25 September 2017. p. 38.

- ^ The Peoples of Ancient Italy. Germany. 20 November 2017. p. 17.

- ^ Suetonius. Life of Claudius. 42.

- ^ "An illustrated lexicon about the ancient myths". Foundation for the Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (LIMC). 2009. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- ^ Rix, Helmut, ed. (1991). Etruskische Texte. ScriptOralia (in German and Etruscian). Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag. ISBN 3-8233-4240-1. 2 vols.

- ^ Cary, M.; Scullard, H. H. (1979). A History of Rome (3rd ed.). p. 24. ISBN 0-312-38395-9.

- ^ The religiosity of the Etruscans most clearly manifested itself in the so-called 'discipline', that complex of rules regulating relations between men and gods. Its main basis was the scrupulous search for the divine will by all available means; ... the reading and interpretation of animal entrails, especially the liver ... and the interpretation of lightning. (Pallottino 1975, p. 143)

- ^ Livius, Titus. "V.1". History of Rome.

...a people more than any others dedicated to religion, the more as they excelled in practicing it.

- ^ Maximus, Valerius. "1.1". Factorum et Dictorum Memorabilia.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pallottino 1975, p. 154

- ^ De Divinatione, section 4.

- ^ Seneca the Younger. "II.32.2". Naturales Quaestiones.

- ^ Krauskopf, I. 2006. "The Grave and Beyond." The Religion of the Etruscans. edited by N. de Grummond and E. Simon. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 73–75.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Le Glay, Marcel. (2009). A history of Rome. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-8327-7. OCLC 760889060.

- ^ Dates from De Grummond & Simon (2006), p. vii.

- ^ Jannot, Jean-René (2005). Religion in Ancient Etruria. Translated by Whitehead, Jane. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 15. ISBN 0299208400.

- ^ Pallottino 1975, p. 148

References[]

- Bonfante, Giuliano; Bonfante, Larissa (2002). The Etruscan Language: an Introduction. Manchester: University of Manchester Press. ISBN 0-7190-5540-7.

- Bonnefoy, Yves (1992). Roman and European Mythologies. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-06455-7. Translated by Wendy Doniger, Gerald Honigsblum.

- De Grummond; Nancy Thomson (2006). Etruscan Mythology, Sacred History and Legend: An Introduction. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology. ISBN 1-931707-86-3.

- De Grummond, Nancy Thomson; Simon, Erika, eds. (2006). The Religion of the Etruscans. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-70687-1.

- Dennis, George (1848). The Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria. London: John Murray. Available in the Gazetteer of Bill Thayer's Website at [1]

- Pallottino, M. (1975). Ridgway, David (ed.). The Etruscans. Translated by Cremina, J (Revised and Enlarged ed.). Bloomington & London: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-32080-1.

- Richardson, Emeline Hill (1976) [1964]. The Etruscans: Their Art and Civilization. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-71234-6.

- Rykwert, Joseph (1988). The Idea of a Town: the Anthropology of Urban Form in Rome, Italy and the Ancient World. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-68056-4.

- Swaddling, Judith; Bonfante, Larissa (2006). Etruscan Myths. University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-70606-5.

- Thulin, Carl (1906). Die Götter des Martianus Capella und der Bronzeleber von Piacenza (in German). Alfred Töpelmann.

External links[]

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius (1923) [44 BC]. W.A. Falconer (ed.). Cicero on Divination. Loeb Classical Library. XX. Harvard University Press.

- William P. Thayer (2008). "Cicero on Divination". Lacus Curtius. University of Chicago. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius (2009) [44 BC]. "De Divinatione". The Latin Library (in Latin). Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- Etruscan religion

- Etruscan mythology

- Roman mythology