Everyman (play)

| Everyman | |

|---|---|

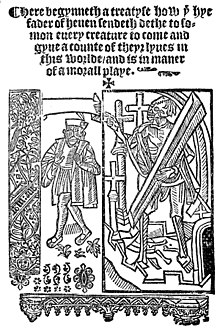

Frontispiece from edition of Everyman published by John Skot c. 1530. | |

| Written by | unknown; anonymous translation of Elckerlijc, by Petrus Dorlandus |

| Characters | |

| Date premiered | c. 1510 |

| Original language | Middle English |

| Subject | Reckoning, Salvation |

| Genre | Morality play |

The Somonyng of Everyman (The Summoning of Everyman), usually referred to simply as Everyman, is a late 15th-century morality play. Like John Bunyan's 1678 Christian novel The Pilgrim's Progress, Everyman uses allegorical characters to examine the question of Christian salvation and what Man must do to attain it.

Summary[]

The will is that the good and evil deeds of one's life will be tallied by God after death, as in a ledger book. The play is the allegorical accounting of the life of Everyman, who represents all mankind. In the course of the action, Everyman tries to convince other characters to accompany him in the hope of improving his life. All the characters are also mystical; the conflict between good and evil is shown by the interactions between the characters. Everyman is being singled out because it is difficult for him to find characters to accompany him on his pilgrimage. Everyman eventually realizes through this pilgrimage that he is essentially alone, despite all the personified characters that were supposed necessities and friends to him. Everyman learns that when you are brought to death and placed before God, all you are left with are your own good deeds.

Sources[]

The play was written in Middle English during the Tudor period, but the identity of the author is unknown. Although the play was apparently produced with some frequency in the seventy-five years following its composition, no production records survive.[1]

There is a similar Dutch-language morality play of the same period called Elckerlijc. In the early 20th century, scholars did not agree on which of these plays was the original, or even on their relation to a later Latin work named Homulus.[2][3] By the 1980s, Arthur Cawley went so far as to say that the "evidence for … Elckerlijk is certainly very strong",[4] and now Davidson, Walsh, and Broos hold that "more than a century of scholarly discussion has ... convincingly shown that Everyman is a translation and adaptation from the Dutch Elckerlijc".[5]

Setting[]

The cultural setting is based on the Roman Catholicism of the era. Everyman attains afterlife in heaven by means of good works and the Catholic Sacraments, in particular Confession, Penance, Unction, Viaticum and receiving the Eucharist.

Synopsis[]

The oldest surviving example of the script begins with this paragraph on the frontispiece:

Here begynneth a treatyſe how þe hye Fader of Heuen ſendeth Dethe to ſomon euery creature to come and gyue a counte of theyr lyues in this worlde, and is in maner of a morall playe. Here begins a treatise how the high Father of Heaven sends Death to summon every creature to come and give account of their lives in this world, and is in the manner of a moral play.

After a brief prologue asking the audience to listen, God speaks, lamenting that humans have become too absorbed in material wealth and riches to follow Him, so He commands Death to go to Everyman and summon him to heaven to make his reckoning. Death arrives at Everyman's side to tell him it is time to die and face judgment. Upon hearing this, Everyman is distressed, so begs for more time. Death denies this, but will allow Everyman to find a companion for his journey.[6]

Everyman's friend Fellowship promises to go anywhere with him, but when he hears of the true nature of Everyman's journey, he refuses to go. Everyman then calls on Kindred and Cousin and asks them to go with him, but they both refuse. In particular, Cousin explains a fundamental reason why no people will accompany Everyman: they have their own accounts to write as well. Afterwards, Everyman asks Goods, who will not come: God's judgment will be severe because of the selfishness implied in Goods's presence.[7]

Everyman then turns to Good Deeds, who says she would go with him, but she is too weak as Everyman has not loved her in his life. Good Deeds summons her sister Knowledge to accompany them, and together they go to see Confession. In the presence of Confession, Everyman begs God for forgiveness and repents his sins, punishing himself with a scourge. After his scourging, Everyman is absolved of his sins, and as a result, Good Deeds becomes strong enough to accompany Everyman on his journey with Death.[8]

Good Deeds then summons Beauty, Strength, Discretion and Five Wits to join them, and they agree to accompany Everyman as he goes to a priest to take sacrament. After the sacrament, Everyman tells them where his journey ends, and again they all abandon him – except for Good Deeds. Even Knowledge cannot accompany him after he leaves his physical body, but will stay with him until the time of death.[9]

Content at last, Everyman climbs into his grave with Good Deeds at his side and dies, after which they ascend together into heaven, where they are welcomed by an Angel. The play closes as the Doctor enters and explains that in the end, a man will only have his Good Deeds to accompany him beyond the grave.[10]

Adaptations[]

A modern stage production of Everyman did not appear until July 1901 when The Elizabethan Stage Society of William Poel gave three outdoor performances at the Charterhouse in London.[11] Poel then partnered with British actor Ben Greet to produce the play throughout Britain, with runs on the American Broadway stage from 1902 to 1918,[12] and concurrent tours throughout North America. These productions differed from past performances in that women were cast in the title role, rather than men. Film adaptations of the 1901 version of the play appeared in 1913 and 1914, with the 1913 film being presented with an early color two-process pioneered by Kinemacolor.[13][14]

A version was filmed for Australian TV in 1964.

Another well-known version of the play is Jedermann by the Austrian playwright Hugo von Hofmannsthal, which has been performed annually at the Salzburg Festival since 1920,[15] and adapted into film several times. Frederick Franck published a modernised version of the tale entitled "Everyone", drawing on Buddhist influence.[16] A direct-to-video film of Everyman was made in 2002, directed by John Farrell, which updated the setting to the early 21st century, including Death as a businessman in dark glasses with a briefcase, and Goods being played by a talking personal computer.[17]

A modernized adaptation by Carol Ann Duffy, the Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom, with Chiwetel Ejiofor in the title role, was performed at the National Theatre from April to July 2015.[18]

In December 2016, Moravian College presented Everyman on Trial, a contemporary adaptation written and directed by Christopher Shorr.[citation needed] Branden Jacobs-Jenkins' adaptation, titled Everybody, premiered in 2017 at the Pershing Square Signature Center in New York City.[19]

Notes[]

- ^ Wilkie & Hurt 2000.

- ^ Tigg 1939.

- ^ de Vocht 1947.

- ^ Cawley 1984, p. 434.

- ^ Davidson, Walsh & Broos 2007.

- ^ Everyman, lines 1–183[incomplete short citation]

- ^ Everyman, lines 184–479

- ^ Everyman, lines 480–653

- ^ Everyman, lines 654–863

- ^ Everyman, lines 864–922

- ^ Kuehler 2008, pp. 3–11.

- ^ Everyman at the Internet Broadway Database

- ^ Everyman (1913) at IMDb.

- ^ Everyman (1914) at IMDb.

- ^ Banham 1998, p. 491.

- ^ Mateer 2001.

- ^ Everyman (2002) at IMDb.

- ^ Sutcliffe 2015.

- ^ "Theater review: Everybody gives a medieval morality tale a few modern twists" by David Cote, Time Out New York, 21 February 2017

References[]

- Banham, Martin, ed. (1998), The Cambridge Guide to Theatre, Cambridge: Cambridge UP, ISBN 0-521-43437-8

- Cawley, A. C. (1984), "Rev. of The Dutch Elckerlijc Is Prior to the English Everyman, by E. R. Tigg", Review of English Studies, 35 (139): 434, JSTOR 515829

- Davidson, Clifford; Walsh, Martin W.; Broos, Ton J. (2007). "Everyman and Its Dutch Original, Elckerlijc – Introduction". University of Rochester. Robbins Library Digital Projects. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- Kuehler, Stephen G. (2008), Concealing God: The Everyman Revival, 1901–1903 (PhD. thesis), Tufts University

- Mateer, Megan (4 July 2001). Everyman's God. SITM (Société internationale pour l'étude du théâtre médiéval). Groningen, Netherlands.

- Schreiber, Earl G. (1975), Everyman in America, Comparative Drama 9.2, pp. 99–115.

- Sutcliffe, Tom (2 May 2015), "Everyman, Far from the Madding Crowd, Empire, Anne Enright, Christopher Williams", Saturday Review, BBC Radio 4

- Speaight, Robert (1954), William Poel and the Elizabethan revival, London: Heinemann, pp. 161–168.

- Tigg, E. R. (1939), "Is Elckerlyc prior to Everyman?", Journal of English and Germanic Philology, 38: 568–596, JSTOR 27704551

- de Vocht, Henry (1947), Everyman: A Comparative Study of Texts and Sources, Material for the Study of the Old English Drama, 20, Louvain: Librairie Universitaire

- Wilkie, Brian; Hurt, James, eds. (2000). Literature of the Western World, Volume I, The Ancient World Through the Renaissance (5th ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-0130186669.

Editions[]

- Greg, Walter Wilson, ed. (1904). Everyman from the edition by John Skot. Louvain: Uystpruyst.

- Farmer, John S., ed. (1912). Everyman, facsimile edition. The Tudor Facsimile Texts.

- Cawley, A. C. (1961), Everyman and Medieval Miracle Plays, Everyman's Library, ISBN 0-460-87280-X

- Davidson, Clifford; Walsh, Martin W.; Broos, Ton J., eds. (2007). "Everyman and Its Dutch Original". Robbins Library Digital Projects, University of Rochester. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

Further reading[]

- Cawley, A. C. (1989), "Everyman", Dictionary of the Middle Ages, ISBN 0-684-17024-8

- Meijer, Reinder (1971), Literature of the Low Countries: A Short History of Dutch Literature in the Netherlands and Belgium, New York: Twayne Publishers, pp. 55–57, 62, ISBN 978-9024721009

- Takahashi, Genji (1953), A Study of Everyman with Special Reference to the Source of its Plot, Ai-iku-sha, pp. 33–39, OCLC 8214306

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Everyman. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Everyman (play) |

- Full Text, Modern English version of Everyman

- A Student Guide to Everyman

Everyman public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Everyman public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- 1495 plays

- 1520s plays

- British plays adapted into films

- English plays

- Everyman

- Christian plays

- Middle English literature

- Religious vernacular drama

- Works of unknown authorship