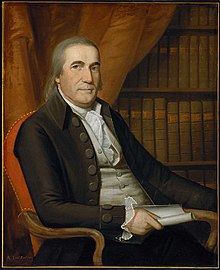

Ezra L'Hommedieu

| Ezra L'Hommedieu | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 30 August 1734 |

| Died | 27 September 1811 |

| Occupation | Politician |

Ezra L'Hommedieu (August 30, 1734 – September 27, 1811) was an American lawyer and statesman from Southold, New York in Suffolk County, Long Island. He was a delegate for New York to the Continental Congress (1779 to 1783) and again in 1788. His national offices overlapped with those he served in the state: in the State Assembly (1777-1783) and in the state senate (1784-1792) and (1794-1809); he was a member of the state constitutional convention in 1801. He also served in local offices, as clerk of Suffolk County from January 1784 to March 1810 and from March 1811 until his death that year. He was a regent of the University of the State of New York.

Representing the New York City Chamber of Commerce to gain federal support, L'Hommedieu chose the site for the Montauk Point Lighthouse and designed it in 1796; it was the first to be built in the state. It was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2012.

Biography[]

Ezra L'Hommedieu was born in Southold, Long Island to Benjamin and Martha (Bourn) L'Hommedieu; they were of Dutch, English and French Huguenot ancestry. He was a great-grandson of, among others, English immigrants Nathaniel and Grizzell (Brinley) Sylvester, who had owned all of Shelter Island (8,000 acres) in the 17th century.[1] He was privately educated before going to Yale College, where he graduated in 1754. He read law and established a law practice in Southold and New York City.

As a lawyer, L'Hommedieu came to consider British tax legislation oppressive and even "illegal."[2] He became caught up in revolutionary fervor, moving from Long Island to Connecticut after occupation of the former in 1776 by the British, and aiding other refugees get to the northern shore. Although George Washington had promised Continental aid to the refugees, L'Hommedieu spent his own money to help support them.[3]

He became active in provincial and state politics, serving in the State Assembly (1777-1783) and in the state senate (1784-1792) and (1794-1809).[4] He also served in local offices, as clerk of Suffolk County from January 1784 to March 1810, and from March 1811 until his death that year.[4]

He was appointed by the New York Assembly as the state representative to the Continental Congress, serving 1779-1783[3] and in 1788. He continued to be politically active and in 1801 was a delegate to the state constitutional convention.[4]

L'Hommedieu was a candidate in 1789 to become one of New York's first two United States senators, to be elected by the state legislature. In the midst of a procedural stalemate in July of that year, the New York Council of Revision held that the state assembly and senate, respectively, should name candidates until both houses concurred on two nominees. The senate confirmed the assembly's choice of Philip Schuyler for one Senate seat but rejected its second nominee, James Duane, proposing L'Hommedieu in Duane's stead. The assembly rejected L'Hommedieu by a 34-24 vote. Rufus King was thereafter approved by both houses for the second Senate seat.[5]

Widely respected for his integrity and intelligence, L'Hommedieu represented the New York City Chamber of Commerce in discussions related to a lighthouse at Montauk Point, a federal project on which he advised President George Washington. He made the case that New York City "was first among American ports in the volume of its foreign commerce. By 1797, the harbor was handling a third of the nation’s trade with other countries."[6] Because of the prevailing winds in winter, New York needed the lighthouse to aid ships approaching its harbor. L'Hommedieu chose the site for the lighthouse[7] and designed it.[6] Constructed in 1796, it was the first lighthouse built in New York state and the first public works project of the new United States. It was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 2012.

L'Hommedieu also developed methods of scientific farming, including the use of seashells to fertilize soils. He corresponded on farming with Thomas Jefferson, particularly about crop pests.[8]

Marriage and family[]

He married Charity Floyd on December 24, 1756 (The Salmon Records: A private record of marriages and deaths of the residents of Southold, Suffolk County, NY, Robbins, William A. (NY: NY Genealogical and Bibliographical Society, 1918)). They did not have any children. Charity's brother was General William Floyd, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. After Charity's death, Ezra married again. He had children with his second wife, and some of their descendants continued to live on Long Island in the 20th century.

Later life[]

L'Hommedieu was active in the community and served in other public positions. He was serving as Regent of the State University of New York, which founding he had supported, when he died at age 77. He was buried near the grave of his first wife, the former Charity Floyd, at the Old Southold Burying Ground.

L’Hommedieu’s papers are now in the collection of the Montauk Historical Society.[7]

References[]

- ^ Mac Griswold, The Manor: Three Centuries at a Slave Plantation on Long Island, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013, pp. 8, 263

- ^ Griswold (2013), The Manor, p. 263

- ^ Jump up to: a b Griswold (2013), The Manor, pp. 263-264

- ^ Jump up to: a b c

- United States Congress. "Ezra L'Hommedieu (id: L000549)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- ^ Alexander, Edward P. A Revolutionary Conservative: James Duane of New York. New York: Columbia University Press, 1938, pp. 198-200.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Russell Drumm, "Turning a Montauk Beacon Into a Landmark" Archived 2014-02-03 at the Wayback Machine, Easthampton Star, 2 June 2011, accessed 4 December 2013

- ^ Jump up to: a b Henry Osmer, "Montauk Point Lighthouse Awarded National Landmark Status", Lighthouse Digest, Sep-Oct 2012, accessed 4 December 2012

- ^ Griswold (2013), The Manor, p. 9

External links[]

- United States Congress. "Ezra L'Hommedieu (id: L000549)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- 1734 births

- 1811 deaths

- Continental Congressmen from New York (state)

- 18th-century American politicians

- New York (state) lawyers

- Members of the New York State Assembly

- Huguenot participants in the American Revolution

- Yale University alumni

- 19th-century American lawyers