Fabric softener

A fabric softener (American English) or fabric conditioner (British English) is a conditioner that is typically applied to laundry during the rinse cycle in a washing machine to reduce harshness in clothes that are dried in air after machine washing. In contrast to laundry detergents, fabric softeners may be regarded as a kind of after-treatment laundry aid.[1]

A wrinkle releaser is a similar, more dilute preparation meant to be sprayed onto fabric directly.

Mechanism of action[]

Machine washing puts great mechanical stress on textiles, particularly natural fibers such as cotton and wool. The fibers at the fabric surface are squashed and frayed, and this condition hardens while drying the laundry in air, giving the laundry a harsh feel. Adding a liquid fabric softener to the final rinse (rinse-cycle softener) results in laundry that feels softer.[2][1]

In the US and UK laundry is mostly dried in mechanical dryers, and the tumbling of the laundry in the dryer has its own softening effect. Therefore, fabric softeners in the US and UK are used rather to impart antistatic properties and a pleasant smell to the laundry. Fabric softeners are usually either in the form of a liquid, which is added to the washing machine during the rinse cycle (either by the machine itself or through use of a dispensing ball); or as a dryer sheet which is added to the moist laundry at the beginning of the dryer cycle. Liquid fabric softeners can be added manually during the rinse cycle or automatically if the machine has a dispenser designed for this purpose. Liquid fabric softeners may also be poured onto a piece of laundry to be dried, such as a wash cloth, and it will be distributed as the laundry is tumbled.

Fabric softeners coat the surface of a fabric with chemical compounds that are electrically charged, causing threads to "stand up" from the surface and thereby imparting a softer and fluffier texture. Cationic softeners bind by electrostatic attraction to the negatively charged groups on the surface of the fibers and neutralize their charge. The long aliphatic chains then line up towards the outside of the fiber, imparting lubricity.

Fabric softeners impart antistatic properties to fabrics, and thus prevent the build-up of electrostatic charges on synthetic fibers, which in turn eliminates fabric cling during handling and wearing, crackling noises, and dust attraction. Also, fabric softeners make fabrics easier to iron and help reduce wrinkles in garments. In addition, they reduce drying times so that energy is saved when softened laundry is tumble-dried. Additionally, they can also impart a pleasant fragrance to the laundry.[1]

Fabric softeners[]

Early cotton softeners were typically based on a water emulsion of soap and olive oil, corn oil, or tallow oil.[citation needed] Softening compounds differ in affinity to various fabrics. Some work better on cellulose-based fibers (i.e., cotton), others have higher affinity to hydrophobic materials like nylon, polyethylene terephthalate, polyacrylonitrile, etc. New silicone-based compounds, such as polydimethylsiloxane, work by lubricating the fibers. Manufacturers use derivatives with amine- or amide-containing functional groups as well. These groups improve the softener's binding to fabrics.

As softeners are often hydrophobic, they commonly occur in the form of an emulsion.[3] In the early formulations, manufactures used soaps as emulsifiers. The emulsions are usually opaque, milky fluids. However, there are also microemulsions, where the droplets of the hydrophobic phase are substantially smaller[not specific enough to verify]. Microemulsions provide the advantage of increased ability of smaller particles to penetrate into the fibers. Manufacturers often use a mixture of cationic and non-ionic surfactants as an emulsifier. Another approach is a polymeric network, an emulsion polymer.

In addition to fabric softening chemicals, fabric softeners may include acids or bases to maintain optimal pH for absorption, silicone-based anti-foaming agents, emulsion stabilizers, fragrances, and colors.

Cationic fabric softeners[]

Rinse-cycle softeners usually contain cationic surfactants of the quaternary ammonium type as the main active ingredient. Cationic surfactants adhere well to natural fibers (wool, cotton), but less so to synthetic fibers. Cationic softeners are incompatible with anionic surfactants in detergents because they combine with them to form a solid precipitate. This requires that the softener be added in the rinse cycle.[4] Fabric softener reduces the absorbency of textiles, which adversely affects the function of towels and microfiber cloth.[5]

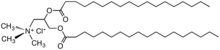

Formerly, the active material of most softeners in Europe, the United States, and Japan, was distearyldimethylammonium chloride (DSDMAC) or related quat salts. Due to their poor biodegradability, such tallow-derived compounds were replaced by the more labile ester-quats in the 1980s and 1990s.

Conventional softeners, which contain 4–6% active material, have been partially replaced in many countries by softener concentrates having some 12–30 % active material.

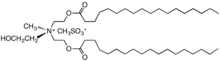

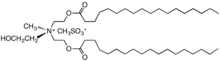

- Cationic surfactants used as fabric softeners

Diethyl ester dimethyl ammonium chloride (DEEDMAC)

TEAQ (triethanolamine quat)

Distearyldimethylammonium chloride (DSDMAC)

Anionic fabric softeners[]

Anionic softeners and antistatic agents can be, for example, salts of monoesters and diesters of phosphoric acid and the fatty alcohols. These are often used together with the conventional cationic softeners. Cationic softeners are incompatible with anionic surfactants in detergents because they combine with them to form a solid precipitate. This requires that they be added in the rinse cycle. Anionic softeners can combine with anionic surfactants directly. Other anionic softeners can be based on smectite clays. Some compounds, such as ethoxylated phosphate esters, have softening, anti-static, and surfactant properties.[6]

Risks[]

As with soaps and detergents, fabric softeners may cause irritant dermatitis.[7] Manufacturers produce some fabric softeners without dyes and perfumes to reduce the risk of skin irritation. Fabric softener overuse may make clothes more flammable, due to the fat-based nature of most softeners. Some deaths have been attributed to this phenomenon,[8] and fabric softener makers recommend not using them on clothes labeled as flame-resistant.[9]

Additional reading[]

- Terlep, Sharon (16 December 2016). "Millennials Are Fine Without Fabric Softener; P&G Looks to Fix That". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Eduard Smulders; Eric Sung (2012). "Laundry Detergents, 2. Ingredients and Products". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.o15_013.

- ^ Eduard Smulders; Wolfgang Rybinski; Eric Sung; Wilfried Rähse; Josef Steber; Frederike Wiebel; Anette Nordskog (2007). "Laundry Detergents". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. pp. 86–87. doi:10.1002/14356007.a08_315.pub2.

- ^ Kumar, Asim; Choudhury, Roy (2017). "Principles of Textile Finishing". Woodhead Publishing Series in Textiles: 109–148 – via Science Direct.

- ^ Wang, Linda (14 Apr 2008). "Dryer Sheets — The science that gives clothing a soft feel and fresh scent as it prevents static cling". Chemical and Engineering News. 86 (15): 47. ISSN 0009-2347.

- ^ Morrison, Chris (2009-11-30). "How Dryer Sheets Work". HowStuffWorks. Retrieved 2021-01-17.

- ^ "Fabric softener and anti-static compositions – Patent 4118327". Freepatentsonline.com. 1977-03-28. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ^ "Contact dermatitis". Medline. Retrieved 2015-10-24.

- ^ "Liquid fabric softener may make clothes more flammable: Quebec coroner". CBC. Retrieved 2015-11-20.

- ^ Heloise (2001-11-28). "Cleaning Flame-Retardant Clothing". Good Housekeeping. Retrieved 2020-12-06.

- Laundry substances

- Cleaning products