Facetotecta

| Facetotecta | |

|---|---|

| |

| Y-cyprid | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Crustacea |

| Class: | Thecostraca |

| Subclass: | Facetotecta Grygier, 1985 |

| Family: | Hansenocarididae Itô, 1985 |

| Genus: | Hansenocaris Itô, 1985 |

| Species | |

|

See text | |

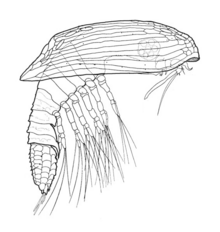

Facetotecta is a poorly known subclass of thecostracan crustaceans.[1] The adult forms have never been recognised, and the group is known only from its larvae, the "y-nauplius" and "y-cyprid" larvae.[2] They are mostly found in the north Atlantic Ocean, neritic waters around Japan,[3] and the Mediterranean Basin, where they also survive in brackish water.[4]

History[]

The German zoologist Christian Andreas Victor Hensen first collected facetotectans from the North Sea in 1887, but assigned them to the copepod family Corycaeidae; later Hans Jacob Hansen named them "y-nauplia", assuming them to be the larvae of unidentified barnacles.[5] More recently, it has been suggested that, since there is a potential gap in the tantulocarid life cycle, y-larvae may be the larvae of tantulocarids. However, this would be "a very tight fit", and it is more likely that the adult forms have not yet been seen.[2] Genetic analysis using 18S ribosomal DNA reveal Facetotecta to be the sister group to the remaining Thecostraca (Ascothoracida and Cirripedia).[6]

Life cycle[]

Nauplius[]

Y-nauplii are 250–620 micrometres (0.010–0.024 in) long,[2] with a faceted cephalic shield, from which the group derives its name.[7] The abdomen is relatively long, and also ornamented.[2] In common with other thecostracans, Facetotecta pass through five naupliar instars before undergoing a single cyprid phase.[5]

Cyprid[]

The presence of a distinctive cyprid larva indicates that the Facetotecta is a member of the Thecostraca. A number of species have been described on the basis of a y-cyprid alone.[8] As in barnacles, the cyprid is adapted to seeking a place to settle as an adult. It has compound eyes, can walk using its antennae, and is capable of producing an adhesive glue.[9]

Juvenile[]

In 2008, a juvenile form was artificially produced by treating y-larvae with the hormone 20-hydroxyecdysone, which stimulated ecdysis and the transition to a new life phase. The resulting animal, named the ypsigon, was slug-like, apparently unsegmented, and limbless.[9][10]

Adults[]

While they have never been seen, the adult facetotectans may be endoparasites of other animals, some of which could be inhabitants of coral reefs.[11]

Species[]

Eleven species are currently recognised,[3] while one species which is assigned to Hansenocaris – H. hanseni (Steuer, 1905) – is of uncertain affinities:[5]

- Itô, 1985

- Belmonte, 2005

- Itô, 1989

- Kolbasov & Høeg, 2003

- Belmonte, 2005

- Belmonte, 2005

- Itô, 1985

- Kolbasov & Grygier, 2007

- Itô, 1985

- Belmonte, 2005

- Itô, 1986

References[]

- ^ Chan, Benny K. K.; Dreyer, Niklas; Gale, Andy S.; Glenner, Henrik; et al. (2021). "The evolutionary diversity of barnacles, with an updated classification of fossil and living forms". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa160.

- ^ a b c d Joel W. Martin; George E. Davis (2001). An Updated Classification of the Recent Crustacea (PDF). Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. p. 132.

- ^ a b Daphne Cuvelier (April 4, 2005). "Hansenocaris Itô, 1985". World Register of Marine Species.

- ^ Genuario Belmonte (2005). "Y-nauplii (Crustacea, Thecostraca, Facetotecta) from coastal waters of the Salento Peninsula (south eastern Italy, Mediterranean Sea) with descriptions of four new species". . 1 (4): 254–266. doi:10.1080/17451000500202518.

- ^ a b c E. A. Ponomarenko (2006). "Facetotecta – Unsolved Riddle of Marine Biology". . 32 (Suppl. 1): S1–S10. doi:10.1134/S1063074006070017.

- ^ Marcos Pérez-Losada; Jens T. Høeg; Gregory A. Kolbasov; Keith A. Crandall (2002). "Reanalysis of the relationships among the Cirripedia and the Ascothoracida and the phylogenetic position of the Facetotecta (Maxillopoda: Thecostraca) using 18S rDNA sequences". Journal of Crustacean Biology. 22 (3): 661–669. doi:10.1651/0278-0372(2002)022[0661:ROTRAT]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Christopher Taylor (February 23, 2008). "The secret of y-larvae". Catalogue of Organisms.

- ^ Gregory A. Kolbasov; Mark J. Grygier; Viatcheslav V. Ivanenko; Alejandro A. Vagelli (2007). "A new species of the y-larva genus Hansenocaris Itô, 1985 (Crustacea: Thecostraca: Facetotecta) from Indonesia, with a review of y-cyprids and a key to all their described species" (PDF). Raffles Bulletin of Zoology. 55 (2): 343–353.

- ^ a b Gerhard Scholtz (2008). "Zoological detective stories: the case of the facetotectan crustacean life cycle". Journal of Biology. 7 (5): 16. doi:10.1186/jbiol77. PMC 2447532. PMID 18598383.

- ^ Henrik Glenner; Jens T. Høeg; Mark J. Grygier; Yoshihisa Fujita (2008). "Induced metamorphosis in crustacean y-larvae: Towards a solution to a 100-year-old riddle". BMC Biology. 6: 21. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-6-21. PMC 2412843.

- ^ Mark Grygier; Jens T. Høeg; Yoshihisa Fujita (July 2004). Introduction to the tremendous diversity of y-larvae (Crustacea: Maxillopoda: Thecostraca: Facetotecta) in inshore coral reef plankton at Sesoko Island, Okinawa, Japan (PDF). 10th International Coral Reef Symposium. Biodiversity and Diversification in the Indo-West Pacific. Okinawa, Japan. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-11.

- Maxillopoda

- Parasitic crustaceans