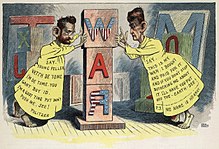

Fake news in the United States in the 1890s

Fake news in the United States in the 1890s was recognized. One editorialist wrote in 1896 that:

The American newspapers are fairly beating their own record at the present time in their success in getting up sensations and setting afloat fake news. . . . our people are in a frame of mind which accepts without question the most absurd statements the mind of man can conceive, and even try to invent excuses for their credulity.[1]

Some examples of fake, or false, news in the decade are the following:

1890: Newspaper wrongly says it faked a story[]

In April 1890, a wire report was sent to newspapers in which it was said that the New-York World "editorially confesses" that a World interview with Grover Cleveland "was a fake."[2][3][4] In the interview, Cleveland was quoted as attacking Charles A. Dana, the top aide to publisher Horace Greeley.[5][6]

Editor told Fred Crawford, the reporter who wrote the story, that he had to retract it. Crawford denied he had made anything up and submitted his resignation.[5][6] He wrote his version of the event for Frank Leslie's Weekly.[7] Crawford's work was defended by other journalists.[4][8]

1890: Census plot[]

On October 5, 1890, the New York World published an article claiming that an effort was being made to falsify U.S. Census returns "for partisan purposes." A census official said the story was "made up out of whole cloth, without a word of truth in it." The Daily Statesman of Portland, Oregon, observed that "The World, on the next day, learning that it had been imposed upon by its Washington news-gatherer, had the grace to make a qualified retraction of the story, but its 'fake' news item will not be checked in its round until it runs out and becomes stale. It will continue to do duty for many a day."[9]

1890: Eastern papers blamed[]

An editorial in The Tribune of Minneapolis, Minnesota, blamed Eastern United States newspapers for what it called the "fake fiend" of false dispatches supposedly describing events taking place in the West (today's Midwest) as a "vain attempt to check emigration." "Whole columns are devoted to stories of local destitution among frontier farmers while a similar state of affairs in Indiana or Virginia is dismissed with a stickful" (a small amount of hand-set type).[10]

1891: Drunken nephews[]

The New York Sun was criticized in The Buffalo Commercial on May 2, 1891, for having printed "fake news" concerning four nephews of the late President Millard Fillmore who were described as "indulging in bar-room orgies." It was said that "the original of the 'fake'" had first appeared in a local newspaper.[11]

1891: 'Murder' a fake[]

The Daily Telegraph of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, reported in its August 4, 1891, edition that the center of fakery was in West Virginia, from whence "came a story that a family named Bromfield had been murdered by Italian laborers."[12]

"The story was well calculated to deceive," the Telegraph said, "and it did fake a number of papers . . . . It turns out that no murder of that kind occurred . . . and the newspaper liar has gathered in some shekels from the gullible fake newspapers."[12]

1892: Not good journalism[]

Fake news is not good journalism, the Marion County (Indiana) Chronicle opined in an article castigating the "florid liars" who engaged in it. "Some of these stories rivalled Baron Munchausen, and it is safe to say not one of them was based on facts worth telling."[13]

1893: McKinley's speech[]

The Daily Democrat of Butler County, Ohio: "If we understand the meaning of fake news[,] it is publishing something that has no foundation whatever; something that never took place—like the speech the Republican [an opposition newspaper] published and said President [William] McKinley delivered when he delivered nothing of the kind."[14]

1895: Yacht race[]

The Western Associated Press was chastised in several newspapers for sending telegraphic bulletins during a yacht race (later called the America's Cup) between the American Defender and the English Valkyrie in which the latter was said to be in the lead for most of the time when actually the American craft had been leading and won the match. "There were numerous uncomplimentary remarks passed about the fake news association which had so completely befogged itself," wrote The New Era of Lancaster, Pennsylvania.[15] "The fake was kept up all the afternoon," said the Sentinel of Rome, New York.[16]

1895: San Salvador 'riots'[]

The New York Sun claimed that the "fraudulent" (Chicago) Associated Press (which it called a "fake news association" and "fake news bureau") had attempted to "stir up a belief that San Salvador was in a state of riot and insurrection." The Sun said the news reports were "more serious than a mere swindling of its patrons and the public with false news."[17]

1895: President's 'assassination'[]

The Associated Press was again in trouble when it telegraphed an announcement to its subscribers in the early morning of October 11, 1895, that President Grover Cleveland had been assassinated. In a dispatch from St. Louis, Missouri, The New-York Times said the AP had sent out the bulletin as a trap for newspapers that were reprinting its dispatches without paying for them. "The trap was baited with the 'fake' sensational report of the President's assassination, and thus The Chicago Associated Press, in pursuance of its wild and reckless and irresponsible methods, imposed this cruel canard upon the country." The Milwaukee (Wisconsin) Daily News reported that the AP threatened to sue United Press, a rival news service, over its story of "how the Associated Press had used the fake."[18]

1896: Sale of Cuba[]

A story spread that Spain was in the process of selling its colony Cuba to Great Britain. Another was that the National Guard of Florida had been assigned the job of preventing it. The New Era of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, observed:

Why, the organized soldiery of Florida amounts to just 1,091 men, and she has no navy. Just how these "cracker" militia were to hurl back the armies of England and drive her flying squadron from our shores was something of a problem which only sensational and fake journalism can properly answer. . . . we shall no doubt always be vexed by such fake news because we will alwlays have fake journals. This is to be regretted, but there seems to be no remedy for it.[1]

1896: Newspaper sellers[]

In Upstate New York, the Buffalo Commercial inveighed against the practice by young newspaper sellers "of crying fake news in order to sell papers." The local police chief had given orders to the newspaper dealers "to instruct all the boys that the crying of fake news must be discontinued." The Commercial wrote that buyers "must not further be deceived by the fake cries which have been used to induce large sales . . . at the behest of unscrupulous dealers."[19]

1896: Phantom 'opium fiends'[]

The Berkeley (California) Gazette decried the publication in an unnamed rival newspaper of the arrival in West Berkeley (via boat from San Francisco) of "seven opium fiends." It wrote: "Of late our evening contemporary has fallen into the habit of publishing fake news which can be so readily discerned that even the dullest person can see it."[20]

Nobody can be found in West Berkeley who saw any such persons as were described . . . in order to fake news enough to fill its columns, the reporter of our contemporary must have imported (in his mind) the seven degraded specimens of humanity. . . .[20]

1896: Senatorial campaign[]

The Indiana Progress and the Snyder County Tribune, both of Pennsylvania, printed the same article, with the same headlines, decrying what they called a "fake news bureau" established by senatorial candidate John Wanamaker. "This fake bureau is worked in connection with the fake Business Men's League, of which one Rudolph Blankenburg, a Prussian who cannot speak the English language correctly, is chairman, and with which a number of millionaires and importers are identified."[21]

1897: Cuban junta[]

In March 1897, The Chicago Chronicle complained that "The most mendacious and industrious 'fake' news bureau in existence is that of the Cuban "junta" (revolutionaries against Spain)" and that the "bogus news syndicate is the most prolific and inventive of any 'fake' enterprise of the kind in this or any other country."[22][23]

1897: Wheat market[]

The Chicago Chronicle blamed fake news for a collapse of prices on the local grain exchange in March 1897. It wrote that "Legitimate news was scarce, fake news, as usual, plentiful . . . ."[24]

The last hour or so, the market was exceptionally weak, due to the dissemination of a bastard piece of so-called information. . . . it was a piece of fake news. . . . It got on the news tickers, then on the private wires, and in a very short time was "news" in all the markets in the country.

The Chronicle commented that "Nonsensical and unfathered as it was, it was the straw that broke the back of the wheat market, [and] . . . when the above fake news came in, they [grain speculators] threw up their hands and their wheat. It was not a question of prices so much as it was to get rid of property that had no real value."[24]

1898: Sinking of the Maine[]

The mysterious explosion and sinking of the U.S. battleship Maine in the Havana, Cuba, harbor on February 15, 1898, resulted in a spate of newspaper articles seeking a cause for the tragedy. The Republican of Phoenix, Arizona, wrote that the disaster:

has been a great chance for the newspaper "fakers," and they have improved it. The amount of news which was not news, that has been imagined, telegraphed and printed about this catastrophe would fill a volume. The fantastic yarns that have been published as truth and the fanciful speculations that have been printed as fact would furnish a library of fiction.[25]

The Arizona Journal-Miner added:

But the Maine disaster is not the only subject which has been used for fake news. There is a certain class of newspapers which seem to be run largely on the fake principle, and when real news is not obtainable, bogus or fake news is substituted. Such papers seem to have good patronage, too.[26]

References[]

- ^ a b "Fake News," The New Era, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, January 25, 1896, Page 4

- ^ "A Fake," The (San Francisco) Call, April 22, 1890, Page 1

- ^ "A Fake," The Patriot, Atchison, Kansas, April 26, 1890, Page 3

- ^ a b "An Episode of Journalism," Oakland (California) Tribune, May 6, 1890, Page 4

- ^ a b The Mail and Express, April 28, 1890, quoted in "The Cleveland Interview," The Washington (D.C.) Critic, April 30, 1890, Page 2

- ^ a b "A Sorry Exhibition," Rochester (New York) Democrat and Chronicle, May 2, 1890, Page 4

- ^ "Crawford's Tale," The (Sacramento) Evening Bee, May 6, 1890, Page 1

- ^ Pittsburg Dispatch, quoted in The Indianapolis Journal, May 14, 1890, Page 4, Column 5

- ^ "One of the World's Fakes," October 17, 1890, Page 2

- ^ "'Fake' News East and West," November 28, 1890, Page 4

- ^ "Work of 'Special Fiends,'" page 11

- ^ a b No headline, Column 2

- ^ Quoted in "John Gray's Corner," Logansport (Indiana) Daily Journal, January 23, 1892, Page 4

- ^ No headline, January 27, 1893, Page 2, Column 1

- ^ No headline, September 11, 1895, Page 2, Column 2

- ^ "That Fake News," Rochester (New York) Democrat and Chronicle, September 10, 1895, Page 2

- ^ "San Salvador: A Libel on the South American Republic," Rochester (New York) Democrat and Chronicle, October 7, 1895, Page 2

- ^ New-York Times, "A Thief Trap Catches the Big Game," October 1, 1895, Page 5

- ^ "No More Fake Cries," March 18, 1896, Page 9

- ^ a b "Fake Journalism," The Gazette, March 28, 1896, Page 2

- ^ "A Muzzled Press," December 9, 1896, The Indiana Progress, Page 3, and, same headlines, Snyder County Tribune, December 11, 1896, Page 2

- ^ Quoted in "The 'Junta' Fake News Bureau," The Daily Times, Chattanooga, Tennessee, March 4, 1897, Page 4

- ^ See similar in "Afraid of 'Fake' Cuban News," The Chicago Chronicle, September 30, 1897, Page 6

- ^ a b "In Commercial Circles, Wheat Trade Swallows Fake News and Is Demoralized," March 12, 1897, page 8

- ^ Quoted in "Genuine and Spurious News," Arizona Journal-Miner, March 9, 1898, Page 2

- ^ "Genuine and Spurious News," March 9, 1898, Page 2

- Fake news by country

- Mass media in the United States