Fasting

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2016) |

Fasting is the willful refrainment from eating and sometimes drinking (see Water fasting and Juice fasting). From a purely physiological context, "fasting" may refer to the metabolic status of a person who has not eaten overnight (see the "break fast"), or to the metabolic state achieved after complete digestion and absorption of a meal. Several metabolic adjustments occur during fasting. Some diagnostic tests are used to determine a fasting state. For example, a person is assumed to be fasting once 8–12 hours have elapsed since the last meal. Metabolic changes of the fasting state begin after absorption of a meal (typically 3–5 hours after eating).

A diagnostic fast refers to prolonged fasting from 1 to 100 hours (depending on age) conducted under observation to facilitate the investigation of a health complication, usually hypoglycemia. Many people may also fast as part of a medical procedure or a check-up, such as preceding a colonoscopy or surgery, or prior to certain medical tests. Intermittent fasting is a technique sometimes used for weight loss that incorporates regular fasting into a person's dietary schedule. Fasting may also be part of a religious ritual, often associated with specifically scheduled fast days, as determined by the religion.

Health effects[]

This article is missing information about health benefits, scientific research about that, fasting in threatment or therapy. (June 2021) |

Medical application[]

Fasting is always practised prior to surgery or other procedures that require general anesthesia because of the risk of pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents after induction of anesthesia (i.e., vomiting and inhaling the vomit, causing life-threatening aspiration pneumonia).[1][2][3] Additionally, certain medical tests, such as cholesterol testing (lipid panel) or certain blood glucose measurements require fasting for several hours so that a baseline can be established. In the case of a lipid panel, failure to fast for a full 12 hours (including vitamins) will guarantee an elevated triglyceride measurement.[4]

Mental health[]

In one review, fasting improved alertness, mood, and subjective feelings of well-being, possibly improving overall symptoms of depression, and boost cognitive performance.[5]

Weight loss[]

Fasting for periods shorter than 24 hours (intermittent fasting) has been shown to be effective for weight loss in obese and healthy adults and to maintain lean body mass.[6][7][8]

Complications[]

In rare occurrences,[9] fasting can lead to the potentially fatal refeeding syndrome upon reinstatement of food intake due to electrolyte imbalance.[10]

Historical medical studies[]

Fasting was historically studied on population under famine and hunger strikes, which led to the alternative name of "starvation diet", as a diet with 0 calories intake per day.[11][12]

Other effects[]

It has been argued that fasting makes one more appreciative of food,[6][13][14][15] and possibly drink.

Political application[]

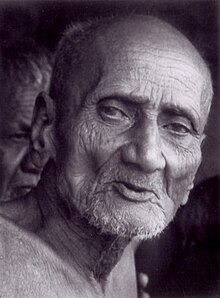

Fasting is often used as a tool to make a political statement, to protest, or to bring awareness to a cause. A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance in which participants fast as an act of political protest, or to provoke feelings of guilt, or to achieve a goal such as a policy change. A spiritual fast incorporates personal spiritual beliefs with the desire to express personal principles, sometimes in the context of a social injustice.[16]

The political leader Gandhi undertook several long fasts as political and social protests. Gandhi's fasts had a significant impact on the British Raj and the Indian population generally.[17]

In Northern Ireland in 1981, a prisoner, Bobby Sands, was part of the 1981 Irish hunger strike, protesting for better rights in prison.[18] Sands had just been elected to the British Parliament and died after 66 days of not eating. His funeral was attended by 100,000 people and the strike ended only after nine other men died. In all, ten men survived without food for 46 to 73 days.

César Chávez undertook a number of spiritual fasts, including a 25-day fast in 1968 promoting the principle of nonviolence, and a fast of 'thanksgiving and hope' to prepare for pre-arranged civil disobedience by farm workers.[16][19] Chávez regarded a spiritual fast as "a personal spiritual transformation".[20] Other progressive campaigns have adopted the tactic.[21]

According to an anonymous Uyghur local government employee quoted in a Radio Free Asia article, during Ramadan 2020 (April 23 to May 23), residents of Makit County (Maigaiti), Kashgar Prefecture, Xinjiang, China were told they could face punishment for fasting including being sent to a re-education camp.[22]

Religious views[]

Fasting is practiced in various religions. Examples include Lent in Christianity; Yom Kippur, Tisha B'av, Fast of Esther, Tzom Gedalia, the Seventeenth of Tamuz, and the Tenth of Tevet in Judaism.[23] Muslims refrain from eating, drinking and sex during the entire daytime for one month, Ramadan, every year.

Details of fasting practices differ. Eastern Orthodox Christians fast during specified fasting seasons of the year, which include not only the better-known Great Lent, but also fasts on every Wednesday and Friday (except on special holidays), together with extended fasting periods before Christmas (the Nativity Fast), after Easter (the Apostles Fast) and in early August (the Dormition Fast). Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons) generally abstain from food and drink for two consecutive meals in a 24-hour period on the first Sunday of each month.[24] Like Muslims, they refrain from all drinking and eating unless they are children or are physically unable to fast. Fasting is also a feature of ascetic traditions in religions such as Hinduism and Buddhism. Mahayana traditions that follow the Brahma's Net Sutra may recommend that the laity fast "during the six days of fasting each month and the three months of fasting each year" [Brahma's Net Sutra, minor precept 30]. Members of the Baháʼí Faith observe a Nineteen Day Fast from sunrise to sunset during March each year.

Baháʼí Faith[]

In the Baháʼí Faith, fasting is observed from sunrise to sunset during the Baháʼí month of 'Ala' ( 1 or 2 March – 19 or 20 March).[25] Bahá'u'lláh established the guidelines in the Kitáb-i-Aqdas. It is the complete abstaining from both food and drink during daylight hours (including abstaining from smoking). Consumption of prescribed medications is not restricted. Observing the fast is an individual obligation and is binding on Baháʼís between 15 years (considered the age of maturity) and 70 years old.[25] Exceptions to fasting include individuals younger than 15 or older than 70; those suffering illness; women who are pregnant, nursing, or menstruating; travellers who meet specific criteria; individuals whose profession involves heavy labor and those who are very sick, where fasting would be considered dangerous. For those involved in heavy labor, they are advised to eat in private and generally to have simpler or smaller meals than are normal.

Along with obligatory prayer, it is one of the greatest obligations of a Baháʼí.[25] In the first half of the 20th century, Shoghi Effendi, explains: "It is essentially a period of meditation and prayer, of spiritual recuperation, during which the believer must strive to make the necessary readjustments in his inner life, and to refresh and reinvigorate the spiritual forces latent in his soul. Its significance and purpose are, therefore, fundamentally spiritual in character. Fasting is symbolic, and a reminder of abstinence from selfish and carnal desires."[26]

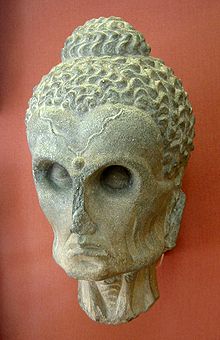

Buddhism[]

Buddhist monks and nuns following the Vinaya rules commonly do not eat each day after the noon meal.[27] This is not considered a fast but rather a disciplined regimen aiding in meditation and good health.

Once when the Buddha was touring in the region of Kasi together with a large sangha of monks he addressed them saying: I, monks, do not eat a meal in the evening. Not eating a meal in the evening I, monks, am aware of good health and of being without illness and of buoyancy and strength and living in comfort. Come, do you too, monks, not eat a meal in the evening. Not eating a meal in the evening you too, monks, will be aware of good health and..... living in comfort.[28]

Fasting is practiced by lay Buddhists during times of intensive meditation, such as during a retreat. During periods of fasting, followers completely stay away from eating animal products, although they do allow consumption of milk. Furthermore, they also avoid eating processed foods and the five pungent foods which are: garlic (Allium sativum), welsh onion (Allium fistulosum), wild garlic (Allium oleraceum), garlic chives (Allium tuberosum), and asafoetida ("asant", Ferula asafoetida).[29] The Middle Path refers to avoiding extremes of indulgence on the one hand and self-mortification on the other. Prior to attaining Buddhahood, prince Siddhartha practiced a short regime of strict austerity and following years of serenity meditation under two teachers which he consumed very little food. These austerities with five other ascetics did not lead to progress in meditation, liberation (moksha), or the ultimate goal of nirvana. Henceforth, prince Siddhartha practiced moderation in eating which he later advocated for his disciples. However, on Uposatha days (roughly once a week) lay Buddhists are instructed to observe the eight precepts[30] which includes refraining from eating after noon until the following morning.[30] The eight precepts closely resemble the ten vinaya precepts for novice monks and nuns. The novice precepts are the same with an added prohibition against handling money.[31]

The Vajrayana practice of Nyung Ne is based on the tantric practice of Chenrezig.[32][33][34] It is said that Chenrezig appeared to an Indian nun[32] who had contracted leprosy and was on the verge of death. Chenrezig taught her the method of Nyung Ne[32] in which one keeps the eight precepts on the first day, then refrains from both food and water on the second. Although seemingly against the Middle Way, this practice is to experience the negative karma of both oneself and all other sentient beings and, as such is seen to be of benefit. Other self-inflicted harm is discouraged.[35][36]

Christianity[]

Fasting is a practice in several Christian denominations and is done both collectively during certain seasons of the liturgical calendar, or individually as a believer feels led by the Holy Spirit; many Christians also fast before receiving Holy Communion (this is known as the Eucharistic Fast).[37][38] In Western Christianity, the Lenten fast is observed by many communicants of the Catholic Church, Lutheran Churches, Methodist Churches, Reformed Churches, Anglican Communion, and the Western Orthodox Churches and is a forty-day partial fast to commemorate the fast observed by Christ during his temptation in the desert.[39][40] While some Western Christians observe the Lenten fast in its entirety, Ash Wednesday and Good Friday are nowadays emphasized by Western Christian denominations as the normative days of fasting within the Lenten season.[41][42]

In the traditional Black Fast, the observant abstains from food for a whole day until the evening, and at sunset, traditionally breaks the fast.[43][44][45] In India and Pakistan, many Christians continue to observe the Black Fast on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday, with some fasting in this manner throughout the whole season of Lent.[46] After attending a worship service (often on Wednesday evenings), it is common for Christians of various denominations often break that day's Lenten fast together through a communal Lenten supper, which is held in the church's parish hall.[47]

Partial fasting within the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, abstaining from meat and milk, takes place during certain times of the year and lasts for weeks.

Roman Catholicism[]

For Catholics, fasting, taken as a technical term, is the reduction of one's intake of food to one full meal (which may not contain meat on Ash Wednesday, Good Friday, and Fridays throughout the entire year unless a solemnity should fall on Friday[48]) and two small meals (known liturgically as collations, taken in the morning and the evening), both of which together should not equal the large meal. Eating solid food between meals is not permitted. Fasting is required of the faithful between the ages of 18 and 59 on specified days. Complete abstinence of meat for the day is required of those 14 and older. Partial abstinence prescribes that meat be taken only once during the course of the day. Meat is understood not to include fish or cold-blooded animals.

Pope Pius XII had initially relaxed some of the regulations concerning fasting in 1956. In 1966, Pope Paul VI in his apostolic constitution Paenitemini, changed the strictly regulated Catholic fasting requirements. He recommended that fasting be appropriate to the local economic situation, and that all Catholics voluntarily fast and abstain. In the United States, there are only two obligatory days of fast – Ash Wednesday and Good Friday;[49] though not under the pain of mortal sin, fasting on all forty days of Lent is "strongly recommended".[50] The Fridays of Lent are days of abstinence: eating meat is not allowed. Pastoral teachings since 1966 have urged voluntary fasting during Lent and voluntary abstinence on the other Fridays of the year. The regulations concerning such activities do not apply when the ability to work or the health of a person would be negatively affected.

Sedevacantist Roman Catholicism[]

The fasting practices of the Sedevacantist Roman Catholic community (who are not in communion with the Holy See) differ from contemporary practices of the Catholic Church.[51]

The Congregation of Mary Immaculate Queen (CMRI), a Sedavacantist Roman Catholic religious congregation, requires fasting for its members on all of the forty days of the Christian season of repentance, Lent (except on the Lord's Day).[51] Fasting is also compulsory on the Ember days and the Vigils of Pentecost Day, Immaculate Conception Day and Christmas Day.[51]

Abstinence from meat is practiced on all Fridays of the year, Ash Wednesday, Holy Saturday and the Vigils of Christmas Day and Immaculate Conception Day, as well as on Ember Days and the Vigil of Pentecost Sunday.[51]

The Eucharistic Fast, for members of the CMRI, means fasting from food and alcohol three hours prior to receiving Holy Communion, and though not obligatory, "Catholics are urged to observe the eucharistic fast from midnight" prior to communing.[52]

Anglicanism[]

The Book of Common Prayer prescribes certain days as days for fasting and abstinence, "consisting of the 40 days of Lent, the ember days, the three rogation days (the Monday to Wednesday following the Sunday after Ascension Day), and all Fridays in the year (except Christmas, if it falls on a Friday)":[53]

A Table of the Vigils, Fasts, and Days of Abstinence, to be Observed in the Year.

- The eves (vigils) before:

- The Nativity of our Lord.

- The Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

- The Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin.

- Easter Day.

- Ascension Day.

- Pentecost.

- St. Matthias.

- St. John Baptist.

- St. Peter.

- St. James.

- St. Bartholomew.

- St. Matthew.

- St. Simon and St. Jude.

- St. Andrew.

- St. Thomas.

- All Saints' Day.

- Note: if any of these Feast-Days fall upon a Monday, then the Vigil or Fast-Day shall be kept upon the Saturday, and not upon the Sunday next before it.

- Days of Fasting, or Abstinence.

- I. The Forty Days of Lent.

- II. The Ember-Days at the Four Seasons, being the Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday after the First Sunday in Lent, the Feast of Pentecost, September 14, and December 13.

- III. The Three Rogation Days, being the Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday, before Holy Thursday, or the Ascension of our Lord.

- IV. All the Fridays in the Year, except Christmas Day.

Saint Augustine's Prayer Book defines "Fasting, usually meaning not more than a light breakfast, one full meal, and one half meal, on the forty days of Lent."[37] Abstinence, according to Saint Augustine's Prayer Book, "means to refrain from some particular type of food or drink. One traditional expression of abstinence is to avoid meat on Fridays in Lent or through the entire year, except in the seasons of Christmas and Easter. It is common to undertake some particular act of abstinence during the entire season of Lent. This self-discipline may be helpful at other times, as an act of solidarity with those who are in need or as a bodily expression of prayer."[54]

In the process of revising the Book of Common Prayer in various provinces of the Anglican Communion the specification of abstinence or fast for certain days has been retained. Generally Lent and Fridays are set aside, though Fridays during Christmastide and Eastertide are sometimes avoided. Often the Ember Days or Rogation Days are also specified, and the eves (vigils) of certain feasts.

In addition to these days of fasting, Anglicans also observe the Eucharistic Fast. Saint Augustine's Prayer Book states that the Eucharistic Fast is a "strict fast from both food and drink from midnight" that is done in "in order to receive the Blessed Sacrament as the first food of the day" in "homage to our Lord".[37] It implores Anglicans to fast for some hours before the Midnight Mass of Christmas Eve, the first liturgy of Christmastide.[37]

From the execution of Charles I, the Supreme Governor of the Church of England, on 30 January 1649, until it was repealed in the Anniversary Days Observance Act 1859, the church included January 30 as a fast day to commemorate his becoming King Charles the Martyr. The Society of King Charles the Martyr, an Anglican Catholicism group, continues to observe January 30 as the Feast Day of St Charles.

Eastern Orthodoxy[]

Eastern Orthodox Christians are required to fast on Wednesdays (in memory of Jesus' betrayal on Spy Wednesday) and Fridays (in memory of Jesus' crucifixion on Good Friday), which means not consuming food until evening (sundown). The supper that is eaten after the fast is broken in the evening must not include shellfish.[55] Additionally, Orthodox Christians abstain from sexual relations on Wednesdays and Fridays throughout the year, as with the entirety of Lent, the Nativity Fast and the fifteen days before the Feast of the Assumption of Mary.[56]

For Eastern Orthodox Christians, fasting is an important spiritual discipline, found in both the Old Testament and the New, and is tied to the principle in Orthodox theology of the synergy between the body (Greek: soma) and the soul (pneuma). That is to say, Orthodox Christians do not see a dichotomy between the body and the soul but rather consider them as a united whole, and they believe that what happens to one affects the other (this is known as the psychosomatic union between the body and the soul).[57][58] Saint Gregory Palamas argued that man's body is not an enemy but a partner and collaborator with the soul. Christ, by taking a human body at the Incarnation, has made the flesh an inexhaustible source of sanctification.[59] This same concept is also found in the much earlier homilies of Saint Macarius the Great.

Fasting can take up a significant portion of the calendar year. The purpose of fasting is not to suffer, but according to Sacred Tradition to guard against gluttony and impure thoughts, deeds and words.[60] Fasting must always be accompanied by increased prayer and almsgiving (donating to a local charity, or directly to the poor, depending on circumstances). To engage in fasting without them is considered useless or even spiritually harmful.[57] To repent of one's sins and to reach out in love to others is part and parcel of true fasting.

Fast days[]

This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (January 2016) |

There are four fasting seasons, which include:

- Great Lent (40 days) and Holy Week (seven days)

- Nativity Fast (40 days)

- Apostles' Fast (variable length)

- Dormition Fast (two weeks)

Wednesdays and Fridays are also fast days throughout the year (with the exception of fast-free periods). In some Orthodox monasteries, Mondays are also observed as fast days (Mondays are dedicated to the angels, and monasticism is called the "angelic life").[58]

Other days occur which are always observed as fast days:

- The paramony or Eve of Christmas and of Theophany (Epiphany)

- Beheading of John the Baptist

- Exaltation of the Cross

Rules[]

Fasting during these times includes abstention from:

- meat, fish, eggs and milk products

- sometimes oil (interpreted variously as abstention from olive oil only, or as abstention from all cooking oils in general), and

- red wine (which is often interpreted as including all wine or alcoholic beverages)

- sexual activity (where fasting is pre-communion)[61]

When a feast day occurs on a fast day, the fast is often mitigated (lessened) to some degree (though meat and dairy are never consumed on any fast day). For example, the Feast of the Annunciation almost always occurs within the Great Lent in the Orthodox calendar: in this case fish (traditionally haddock fried in olive oil) is the main meal of the day.

There are two degrees of mitigation: allowance of wine and oil; and allowance of fish, wine and oil. The very young and very old, nursing mothers, the infirm, as well as those for whom fasting could endanger their health somehow, are exempt from the strictest fasting rules.[57]

On weekdays of the first week of Great Lent, fasting is particularly severe, and many observe it by abstaining from all food for some period of time. According to strict observance, on the first five days (Monday through Friday) there are only two meals eaten, one on Wednesday and the other on Friday, both after the Presanctified Liturgy. Those who are unable to follow the strict observance may eat on Tuesday and Thursday (but not, if possible, on Monday) in the evening after Vespers, when they may take bread and water, or perhaps tea or fruit juice, but not a cooked meal. The same strict abstention is observed during Holy Week, except that a vegan meal with wine and oil is allowed on Great Thursday.[57]

On Wednesday and Friday of the first week of Great Lent the meals which are taken consist of xerophagy (literally, "dry eating") i.e. boiled or raw vegetables, fruit, and nuts.[57] In a number of monasteries, and in the homes of more devout laypeople, xerophagy is observed on every weekday (Monday through Friday) of Great Lent, except when wine and oil are allowed.

Those desiring to receive Holy Communion keep a total fast from all food and drink from midnight the night before (see Eucharistic discipline).

Fast-free days[]

During certain festal times the rules of fasting are done away with entirely, and everyone in the church is encouraged to feast with due moderation, even on Wednesday and Friday. Fast-free days are as follows:

- Bright Week – the period from Pascha (Easter Sunday) through Thomas Sunday (the Sunday after Pascha), inclusive.

- The Afterfeast of Pentecost – the period from Pentecost Sunday until the Sunday of All Saints, inclusive.

- The period from the Nativity of the Lord until (but not including) the eve of the Theophany (Epiphany).

- The day of Theophany.

- For Muslim Community 5 Days restricted for fasting in on a year: 2 days of Eid al-Fitr and 3 days of EID al Adha. [62]

Methodism[]

In Methodism, fasting is considered one of the Works of Piety.[63] "The General Rules of the Methodist Church," written by the founder of Methodism, John Wesley, wrote that "It is expected of all who desire to continue in these societies that they should continue to evidence their desire of salvation, by attending upon all the ordinances of God, such are: the public worship of God; the ministry of the Word, either read or expounded; the Supper of the Lord; family and private prayer; searching the Scriptures; and fasting or abstinence."[64] The Directions Given to Band Societies (25 December 1744) mandated for Methodists fasting and abstinence from meat on all Fridays of the year,[65][66] a practice that was reemphasized by Phoebe Palmer and became standard in the Methodist churches of the holiness movement.[67][68] Additionally, the Discipline of the Wesleyan Methodist Church required Methodists to fast on "the first Friday after New-Year's-day; after Lady-day; after Midsummer-day; and after Michaelmas-day."[65] Historically, Methodist clergy are required to fast on Wednesdays, in remembrance of the betrayal of Christ, and on Fridays, in remembrance of His crucifixion and death.[69][64] Wesley himself also fasted before receiving Holy Communion "for the purpose of focusing his attention on God," and asked other Methodist Christians to do the same.[64] In accordance with Scripture and the teachings of the Church Fathers, fasting in Methodism is done "from morning until evening"; John Wesley kept a more rigorous Friday Fast, fasting from sundown (on Thursday) until sundown (on Friday) in accordance with the liturgical definition of a day.[64][70] The historic Methodist homilies regarding the Sermon on the Mount also stressed the importance of the Lenten fast.[71] The United Methodist Church therefore states that:

There is a strong biblical base for fasting, particularly during the 40 days of Lent leading to the celebration of Easter. Jesus, as part of his spiritual preparation, went into the wilderness and fasted 40 days and 40 nights, according to the Gospels.[72]

Good Friday, which is towards the end of the Lenten season, is traditionally an important day of communal fasting for Methodists.[41] Rev. Jacqui King, the minister of Nu Faith Community United Methodist Church in Houston explained the philosophy of fasting during Lent as "I'm not skipping a meal because in place of that meal I'm actually dining with God".[73]

Oriental Orthodox[]

All Oriental Orthodox churches practice fasting; however, the rules of each church differ. All churches require fasting before one receives Holy Communion. All churches practice fasting on most Wednesdays and Fridays throughout the year as well as observing many other days. Monks and nuns also observe additional fast days not required of the laity.

The Armenian Apostolic Church (with the exception of the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem) has followed the Gregorian Calendar since 1923, making it and the Finnish Orthodox Church the only Orthodox churches to primarily celebrate Easter on the same date as Western Christianity. As a result, the Armenian church's observation of Lent generally begins and ends before that of other Orthodox churches.

Lutheran[]

Martin Luther, the Protestant Reformer, held that fasting served to "kill and subdue the pride and lust of the flesh".[74] As such, the Lutheran churches often emphasized voluntary fasting over collective fasting, though certain liturgical seasons and holy days were times for communal fasting and abstinence.[75][76] Certain Lutheran communities advocate fasting during designated times such as Lent,[40][77] especially on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday.[42][40][78][79] A Handbook for the Discipline of Lent delineates the following Lutheran fasting guidelines:[80]

- Fast on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday with only one simple meal during the day, usually without meat.

- Refrain from eating meat (bloody foods) on all Fridays in Lent, substituting fish for example.

- Eliminate a food or food group for the entire season. Especially consider saving rich and fatty foods for Easter.

- Consider not eating before receiving Communion in Lent.

- Abstain from or limit a favorite activity (television, movies, etc.) for the entire season, and spend more time in prayer, Bible study, and reading devotional material.[80]

It is also considered to be an appropriate physical preparation for partaking of the Eucharist, but fasting is not necessary for receiving the sacrament. Martin Luther wrote in his Small Catechism "Fasting and bodily preparation are certainly fine outward training, but a person who has faith in these words, 'given for you' and 'shed for you for the forgiveness of sin' is really worthy and well prepared."[81]

Reformed[]

John Calvin, the figurehead of the Reformed tradition (the Continental Reformed, Congregational, Presbyterian, and Anglican Churches) held that communal fasts "would help assuage the wrath of God, thus combating the ravages of plague, famine and war."[74] In addition, individual fasting was beneficial in that "in preparing the individual privately for prayer, as well as promoting humility, the confession of guilt, gratitude for God's grace and, of course, discipling lust."[74] As such, many of the churches in the Reformed tradition retained the Lenten fast in its entirety.[39] The Reformed Church in America describes the first day of Lent, Ash Wednesday, as a day "focused on prayer, fasting, and repentance" and considers fasting a focus of the whole Lenten season,[82] as demonstrated in the "Invitation to Observe a Lenten Discipline", found in the Reformed liturgy for the Ash Wednesday service, which is read by the presider:[83]

We begin this holy season by acknowledging our need for repentance and our need for the love and forgiveness shown to us in Jesus Christ. I invite you, therefore, in the name of Christ, to observe a Holy Lent, by self-examination and penitence, by prayer and fasting, by practicing works of love, and by reading and reflecting on God's Holy Word.[83]

Good Friday, which is towards the end of the Lenten season, is traditionally an important day of communal fasting for adherents of the Reformed faith.[41] In addition, within the Puritan/Congregational tradition of Reformed Christianity, special days of humiliation and thanksgiving "in response to dire agricultural and meteororological conditions, ecclesiastsical, military, political, and social crises" are set apart for communal fasting.[84]

In more recent years, many churches affected by liturgical renewal movements have begun to encourage fasting as part of Lent and sometimes Advent, two penitential seasons of the liturgical year. Members of the Anabaptist movement generally fast in private. The practice is not regulated by ecclesiastic authority.[85] Some other Protestants consider fasting, usually accompanied by prayer, to be an important part of their personal spiritual experience, apart from any liturgical tradition.

Moravian[]

Members of the Moravian Church voluntarily fast during the season of Lent, along with making a Lenten sacrifice for the season as a form of penitence.[86]

Pentecostalism[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2019) |

Classical Pentecostalism does not have set days of abstinence and lent, but individuals in the movement may feel they are being directed by the Holy Spirit to undertake either short or extended fasts. Although Pentecostalism has not classified different types of fasting, certain writers within the movement have done so. Arthur Wallis writes about the "Normal Fast" in which pure water alone is consumed.[87] The "Black Fast" in which nothing, not even water, is consumed is also mentioned. Dr. Curtis Ward points out that undertaking a black fast beyond three days may lead to dehydration, may irreparably damage the kidneys, and result in possible death.[88] He further notes that nowhere in the New Testament is it recorded that anyone ever undertook a black fast beyond three days and that one should follow this biblical guideline. In addition to the normal fast and black fast, some undertake what is referred to as the Daniel Fast (or Partial Fast) in which only one type of food (e.g., fruit or fruit and non-starchy vegetables) is consumed.[87] In a Daniel Fast, meat is almost always avoided, in following the example of Daniel and his friends' refusal to eat the meat of Gentiles, which had been offered to idols and not slaughtered in a kosher manner. In some circles of Pentecostals, the term "fast" is simply used, and the decision to drink water is determined on an individual basis.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints[]

For members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), fasting is total abstinence from food and drink accompanied by prayer. Members are encouraged to fast on the first Sunday of each month, designated as Fast Sunday. During Fast Sunday, members abstain from food and drink for two consecutive meals in a 24-hour period;[89] this is usually Sunday breakfast and lunch, thus the fasting occurs between the evening meal on Saturday and the evening meal on Sunday. The money saved by not having to purchase and prepare meals is donated to the church as a fast offering, which is then used to help people in need.[90] Members are encouraged to donate more than just the minimal amount, and be as generous as possible. Church apostle Gordon B. Hinckley stated: "Think ... of what would happen if the principles of fast day and the fast offering were observed throughout the world. The hungry would be fed, the naked clothed, the homeless sheltered. ... A new measure of concern and unselfishness would grow in the hearts of people everywhere."[91] Fasting and the associated donations for use in assisting those in need, are an important principle as evidenced by church leaders addresses on the subject during general conferences of the church.[92]

Sunday worship meetings on Fast Sunday include opportunities for church members to publicly bear testimony of their belief in Jesus Christ and church doctrine during the sacrament meeting portion, often referred to as fast and testimony meeting.[93]

Fasting is also encouraged for members any time they desire to grow closer to God and to exercise self-mastery of spirit over body. Members may also implement personal, family, or group fasts any time they desire to solicit special blessings from God, including health or comfort for themselves or others.[93]

Daniel Fast[]

The Book of Daniel (1:2-20, and 10:2-3) refers to a 10- or 21-day avoidance of foods (Daniel Fast) declared unclean by God in the laws of Moses.[94][95] In modern versions of the Daniel Fast, food choices may be limited to whole grains, fruits, vegetables, pulses, nuts, seeds and oil. The Daniel Fast resembles the vegan diet in that it excludes foods of animal origin.[95] The passages strongly suggest that the Daniel Fast will promote good health and mental performance.[94]

Hinduism[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2018) |

Fasting is an optional part of the Hinduism. Individuals observe different kinds of fasts based on personal beliefs and local customs.[96] Some Hindus fast on certain days of the month such as Ekadasi,[97] Pradosha, or Purnima. Certain days of the week are also set aside for fasting depending on personal belief and favorite deity. For example, devotees of Shiva tend to fast on Mondays,[98] while devotees of Vishnu tend to fast on Thursdays and devotees of Ayyappa tend to fast on Saturdays. Tuesday fasting is common in southern India as well as northwestern India. In the south, it is believed that Tuesday is dedicated to Goddess Mariamman, a form of Goddess Shakti. Devotees eat before sunrise and drink only liquids between sunrise and sunset. Only liquids between a prescribed period, like water fasting, is half fasting. In the North, Tuesday and Saturday are dedicated to Lord Hanuman and devotees are allowed only to consume milk and fruit between sunrise and sunset. Thursday fasting is common among the Hindus of northern India. On Thursdays, devotees listen to a story before opening their fast. On the Thursday fasters also worship Vrihaspati Mahadeva. They wear yellow clothes, and meals with yellow colour are preferred. Women worship the banana tree and water it. Food items are made with yellow-coloured ghee. Thursday is also dedicated to Guru and many Hindus who follow a guru will fast on this day. Fasting during religious festivals is also very common. Common examples are Maha Shivaratri (Most people conduct a strict fast on Maha Shivratri, not even consuming a drop of water ), or the nine days of Navratri (which occurs twice a year in the months of April and October/November during Vijayadashami just before Diwali, as per the Hindu calendar). Karwa Chauth is a form of fasting practised in some parts of India where married women undertake a fast for the well-being, prosperity, and longevity of their husbands. The fast is broken after the wife views the moon through a sieve. In the fifth month (Shravan Maas) of the Hindu calendar, many celebrate Shraavana. During this time some will fast on the day of the week that is reserved for worship of their chosen god(s), while others will fast during the entire month.[99] In the state of Andhra Pradesh, the month of Kartik (month), which begins with the day after Deepavali is often a period of frequent (though not necessarily continuous) fasting for some people, especially women. Common occasions for fasting during this month include Mondays for Lord Shiva, the full-moon day of Karthika and the occasion of Naagula Chaviti.

Methods of fasting also vary widely and cover a broad spectrum. If followed strictly, the person fasting does not partake any food or water from the previous day's sunset until 48 minutes after the following day's sunrise. Fasting can also mean limiting oneself to one meal during the day, abstaining from eating certain food types or eating only certain food types. In any case, the fasting person is not supposed to eat or even touch any animal products (i.e., meat, eggs) except dairy products.For Many Hindu communities during fasting, starchy items such as Potatoes, Sago and Sweet potatoes,[100] purple-red sweet potatoes, amaranth seeds,[101] nuts and shama millet are allowed.[102] Popular fasting dishes in western part of India include Farari chevdo, Sabudana Khichadi or peanut soup.[103]

In Shri Vidya, one is forbidden to fast because the Devi is within them, and starving would in return starve the god. The only exception in Srividya for fasting is on the anniversary of the day one's parents died.

Mahabharata: Anushasana Parva (Book 13)

Yudhishthira asks Bhishma, "what constitutes the highest penances?" Bheeshma states (in section 103) " ....there is no penance that is superior to abstention from food! In this connection is recited the ancient narrative of the discourse between Bhagiratha and the illustrious Brahman (the Grandsire of the Creation).[104]

Bhagiratha says, The vow of fast was known to Indra. He kept it a secret but USANAS first made it known to the universe. Bhagiratha says, "In my opinion, there is no penance higher than fast." Bhagiratha did many sacrifices and gave gifts and says "the present that flowed from me were as copious as the stream of the Ganga herself.(but ..) it is not through the merits of these acts that I have attained this region." Bhagiratha observed the vow of fasting and reached "the region of Brahman". Bheeshma advises Yudhishthira, "Do thou practice this vow (of fasting) of very superior merit that is not known to all."

In section 109, of the same book, Yudhishthira asks Bheesma "what is the highest, most beneficial" and fruitful "of all kinds of fasts in the world". Bheeshma says "fasting on the 12th day of the lunar month" and worship Krishna, for the whole year. Krishna is worshipped in twelve forms as Kesava, Narayana, Madhava, Govinda, Vishnu, the slayer of Madhu, who covered the universe in three steps, the dwarf (who beguiled Mahabali), Sridhara, Hrishikesha, Padmanabha, Damodara, Pundhariksha. and Upendra. After fasting, one must feed a number of brahmans. Bheeshma says " the illustrious Vishnu, that ancient being, has himself said that there is no fast that possesses merit superior to what attach to fast of this kind."[105]

In section 106, of the same book, Yudhishthira says, "the disposition (of observing fasts) is seen in all orders of men including the very Mlechchhas..... What is the fruit that is earned in this world by the man that observes fasts?" Bheeshma replies that he had asked Angiras "the very same question that thou has asked me today." The illustrious Angiras says Brahmans and kshatriya should fast for three nights at a stretch is the maximum. A person who fasts on the eight and fourteenth day of the dark fortnight "becomes freed from maladies of all kinds and possessed of great energy."

Fasting for one meal every day during a lunar month gets various boons according to the month in which he fasts.[106] For example, fasting for one meal every day during Margashirsha, "acquires great wealth and corn".

[]

In some specific periods of time (like Caturmasya or Ekadashi fasting) it is said that one who fasts on these days and properly doing spiritual practice on these days like associating with devotees -sangha, chanting holy names of Hari (Vishnu, Narayana, Rama, Krishna) and similar (shravanam, kirtanam vishno) may be delivered from sins.[97]

Islam[]

In Islam, fasting requires abstinence from food, drink, drugs (including nicotine) and sexual intercourse. However, there is also a broader sense of fasting which includes abstaining from any falsehood in speech and action, abstaining from any ignorant and indecent speech, and from arguing and fighting. Therefore, fasting strengthens control of impulses and helps develop good behavior. During the sacred month of Ramadan, believers strive to purify body and soul and increase their taqwa (good deeds and God-consciousness). This purification of body and soul harmonizes the inner and outer spheres of an individual. Muslims aim to improve their body by reducing food intake and maintaining a healthier lifestyle. Overindulgence in food is discouraged and eating only enough to silence the pain of hunger is encouraged. Muslims believe they should be active, tending to all their commitments and never falling short of any duty. On a moral level, believers strive to attain the most virtuous characteristics and apply them to their daily situations. They try to show compassion, generosity and mercy to others, exercise patience, and control their anger. In essence, Muslims are trying to improve what they believe to be good moral character and habits.

Ramadan[]

Fasting is obligatory for every Muslim one month in the year, during Ramadan. Each day, the fast begins at dawn and ends at sunset. During this time Muslims are asked to remember those who are less fortunate than themselves as well as bringing them closer to God. Non obligatory fasts are two days a week as well as the middle of the month, as recommended by the Prophet Muhammad.

Although fasting at Ramadan is fard (obligatory), exceptions are made for persons in particular circumstances.[107] Muslims are encouraged to fast optionally outside of Ramadan as well, as a way of asking forgiveness from or showing gratitude to God and in many other days.

Ashura[]

Ashura is the Islamic counterpart to the Jewish fast of Yom Kippur, to thank God for saving Moses and the Jewish people from Egypt. It is also encouraged to fast the day before, or the day after, or all three days. The same day also marks the martyrdom of Husayn ibn Ali and his family. Although, it is not obligatory but many Sunni and Shia Muslims both fast on this day.[108][109][110]

Shawwal[]

Some Muslims observe fasting during any six days of Shawwal. The reasoning behind this tradition is that a good deed in Islam is rewarded 10 times, hence fasting 30 days during Ramadan and 6 days during Shawwāl is equivalent to fasting the whole year in fulfillment of the obligation.[111]

Arafah[]

Fasting on the day of Arafah for non-pilgrims is a highly recommended Sunnah which entails a great reward; Allah forgives the sins of two years. Imam An-Nawawi mentioned in his book al-Majmu’, “With regard to the ruling on this matter, Imam As-Shafi’i and his companions said: It is mustahabb (recommended) to fast on the day of Arafah for the one who is not in Arafah.[112] Those who are not performing their hajj may observe fasting to gain the merits of the blessed day.[113]

Dhu al-Hijjah[]

During the first nine days of the month of Dhu al-Hijjah, i.e. the nine days before Eid al-Adha, and from these especially on Day of Arafah and day before Eid al-Adha.

Ayyam al-Bid[]

Ayyam al-Bīḍ or "The White Days", the three days of the full moon. These fall on the 13th, 14th, and 15th of each Islamic month. Fasting in this style results in 32 optional fasts in a lunar year, as fasting in Ramadan is mandatory and it is forbidden to fast on the 13th of Dhu al-Hijjah.

Fast of Dawud[]

Fast of Dawud (David): fasting alternate days the whole year round. This style of fasting is attributed to the prophet Dawud. The discouragement of fasting on Friday alone without also fasting on either Thursday or Saturday is lifted for those fasting consistently in this style. It results in around 140 optional fasts in a lunar year, which is around 355 days long.

Monday and Thursday[]

- Fasting on Monday and Thursday every week. Fasting in this style results in around 90 optional fasts in a lunar year.

Forbidden days[]

Islam forbids fasting on certain days.[114]

Jainism[]

Prior to undertaking a Jain fast, a person must make a vow, or a formal statement of intent.[115] Several medical fasting techniques in modern medical studies is coincidentally found in Jainism. For example, one form of intermittent fasting in Jainism is known as 'ratribhojantyag', the 'tribihar upvas' in Jainism is a 36 hour water fast, et cetera. The main difference between these medical dieting and fasting and the equivalent Jain-fasting is the religious intent of the person who is fasting.

Judaism[]

Fasting for Jews means completely abstaining from food and drink, including water. Traditionally observant Jews fast six days of the year. With the exception of Yom Kippur, fasting is never permitted on Shabbat, for the commandment of keeping Shabbat is biblically ordained and overrides the later rabbinically instituted fast days. (The optional minor fast of the Tenth of Tevet could also override the Shabbat, but the current calendar system prevents this from ever occurring.[116])

Yom Kippur is considered to be the most important day of the Jewish year-cycle and fasting as a means of repentance is expected of every Jewish man or woman above the age of bar mitzvah and bat mitzvah respectively. This is the only fast day mentioned in the Torah (Leviticus 23:26-32). It is so important to fast on this day, that only those who would be put in mortal danger by fasting are exempt, such as the ill or frail (endangering a life is against a core principle of Judaism[117]). Those that do eat on this day are encouraged to eat as little as possible at a time and to avoid a full meal. For some, fasting on Yom Kippur is considered more important than the prayers of this holy day. If one fasts, even if one is at home in bed, one is considered as having participated in the full religious service.

The second major day of fasting is Tisha B'Av, the day approximately 2500 years ago on which the Babylonians destroyed the first Holy Temple in Jerusalem, as well as on which the Romans destroyed the second Holy Temple in Jerusalem about 2000 years ago, and later after the Bar Kokhba revolt when the Jews were banished from Jerusalem, the day of Tisha B'Av was the one allowed exception. Tisha B'Av ends a three-week mourning period beginning with the fast of the 17th of Tammuz. This is also the day when observant Jews remember the many tragedies which have befallen the Jewish people, including the Holocaust.

Tisha B'Av and Yom Kippur are the major fasts and are observed from sunset to the following day's dusk. The remaining four fasts are considered minor. Fasting is only observed from sunrise to dusk, and there is more leniency if the fast represents too much of a hardship to a sick or weak person, or pregnant or nursing woman.

The four public but minor fast days are:

- The Fast of Gedaliah on the day after Rosh Hashanah

- The Fast of the 10th of Tevet

- The Fast of the 17th of Tammuz

- The Fast of Esther, which takes place immediately before Purim

There are other minor customary fast days, but these are not universally observed, and they include:

- "Bahab," (literally an acronym for "Monday, Thursday, Monday") the first two Mondays and first Thursday of the months Cheshvan and Iyar (postponed by a week if Monday is the first of the month.)

- "Yom Kippur Katan," (literally "Little Yom Kippur") the day before every Rosh Chodesh, moved back to Thursday if that day is Saturday

- The Fast of the Firstborn, on the day before Passover, which applies only to first-born sons; this obligation is usually avoided by participating in a siyum and ritual meal that takes precedence over fasting.

It is an Ashkenazic tradition for a bride and groom to fast on their wedding day before the ceremony as the day represents a personal Yom Kippur. In some congregations, repentance prayers that are said on Yom Kippur service are included by the bride and groom in their private prayers before the wedding ceremony.

Aside from these official days of fasting, Jews may take upon themselves personal or communal fasts, often to seek repentance in the face of tragedy or some impending calamity. For example, a fast is sometimes observed if a sefer torah is dropped. The length of the fast varies, and some Jews will reduce the length of the fast through tzedakah, or charitable acts. Mondays and Thursdays are considered especially auspicious days for fasting. Traditionally, one also fasted upon awakening from an unexpected bad dream although this tradition is rarely kept nowadays.

In the time of the Talmud, drought seems to have been a particularly frequent inspiration for fasts. In modern times as well the Israeli Chief Rabbinate has occasionally declared fasts in periods of drought.

Pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica[]

Refraining from food and water with religious purposes has been practiced over the centuries by many Indigenous groups throughout Mesoamerica as part of ceremonial life. Most of the literature around this topic falls under the broader ethnological category of sacrifice, which has been studied broadly by scholars.

Apart from refraining from ingesting food, fasting may involve restrictions such as drinking water or consuming food at specific times, and omitting salt or chile from all food. Sexual abstinence frequently accompanies fasting, and both practices may last periods as short as three days or as long as a year.[118] The ritual expectations around fasting are conditioned by age, gender, kinship ties, social position, and specific ceremonial contexts. For example, sometimes these restrictions are required of persons before they assume ritual posts or perform specific ceremonial obligations. Fasting and sexual abstinence are often observed by all participants in certain rituals—such as those performed to bring rain for planting maize or to end a drought—by those departing on pilgrimages to sacred places, and among extended kinship networks during curing ceremonies. These practices may be necessary before people ingest ritual foods or other substances and before they handle ritual objects or religious images.[119]

In Mesoamerican cultures, human action is regarded as a necessary complement to divine and natural forces in order to achieve specific objectives, such as the beginning or cessation of annual rains, the productivity of a harvest, harmonious relations between the living and the dead, and fertility among humans and domestic animals.[120]

Catherine Good has argued that many Mesoamerican rituals are based on the concept of vital energy, which circulates among humans, the souls of the dead, elements of the natural world, sacred places, and ritual objects, including Roman Catholic saints. Consuming certain foods and plants, and abstaining from sexual relations enables humans to capture, control, and channel the flow of this energy to desired ends.[121]

Sikhism[]

Sikhism does not regard fasting as a spiritual act. Fasting as an austerity or as a mortification of the body by means of wilful hunger is discouraged in Sikhism. Sikhism encourages temperance and moderation in food, i.e., neither starve nor over-eat.[122]

Sikhism does not promote fasting except for medical reasons. The Sikh Gurus discourage the devotee from engaging in this ritual as it "brings no spiritual benefit to the person". The Sikh holy Scripture, Sri Guru Granth Sahib tell us: "Fasting, daily rituals, and austere self-discipline – those who keep the practice of these, are rewarded with less than a shell." (Guru Granth Sahib Ang 216).

If you keep fast, then do it a way so that you adopt the compassion, well being and ask for good will of everyone. "Let your mind be content, and be kind to all beings. In this way, your fast will be successful." (Guru Granth Sahib Ji, Ang 299)

Serve God who alone is your Savior instead indulge into ritual, he is only one who will save you every where: "I do not keep fasts, nor do I observe the month of Ramadaan. I serve only the One, who will protect me in the end. ||1||" (Guru Granth Sahib Ji, Ang 1136)

If you keep fast, to count everyday pledge yourself you will act honest, sincere, controls your desires, mediate. This is a way how you make yourself free of five thieves: "On the ninth day(naomi) of the month, make a vow to speak the Truth, and your sexual desire, anger and desire shall be eaten up. On the tenth day, regulate your ten doors; on the eleventh day, know that the Lord is One. On the twelfth day, the five thieves are subdued, and then, O Nanak, the mind is pleased and appeased. Observe such a fast as this, O Pandit, O religious scholar; of what use are all the other teachings? ||2||" (Guru Granth Sahib Ji, Ang 1245)

Goal of Human is to meet the Lord-groom, so Guru Sahib Ji says: "One who discards this grain, is practicing hypocrisy. She is neither a happy soul-bride, nor a widow. Those who claim in this world that they live on milk alone, secretly eat whole loads of food. ||3|| Without this grain, time does not pass in peace. Forsaking this grain, one does not meet the Lord of the World." (Guru Granth Sahib Ji, Ang 873)

"Fasting on Ekadashi, adoration of Thakurs (stones) one remains away from Hari engaged in the Maya and omens. Without the Guru's word in the company of Saints one does not get refuge no matter how good one looks." (Bhai Gurdas Ji, Vaar 7)[123]

Taoism[]

The bigu (辟谷 "avoiding grains") fasting practice originated as a Daoist technique for becoming a xian (仙 "transcendent; immortal"), and later became a Traditional Chinese medicine cure for the sanshi (三尸 "Three Corpses; the malevolent, life-shortening spirits that supposedly reside in the human body"). Chinese interpretations of avoiding gu "grains; cereals" have varied historically; meanings range from not eating particular foodstuffs such as food grain, Five Cereals (China), or staple food to not eating anything such as inedia, breatharianism, or aerophagia.

Yoga[]

In Yoga principle, it is recommended that one maintains a spiritual fast on a particular day each week (Monday or Thursday). A fast should also be maintained on the full moon day of each month. It is essential on the spiritual fasting day not only to abstain from meals, but also to spend the whole day with a positive, spiritual attitude. On the fasting day, intake of solid food is avoided, with water taken as needed.[124]

Japanese history[]

Japan has used fasting as punishment for meat consumption. Consumption of domesticated animals was banned by Emperor Tenmu in 675 A.D. from April to September due to Buddhist influences; however, wild game was exempt.[125] Nevertheless, these laws were regularly flouted. According to the Engishiki, in the Heian Period, fasts began to be used as punishment for the Buddhist sin of meat consumption, initially for 3 days. Eating meat other than seafood (defined here simply as "meat") was seen by Buddhist elite as a kind of spiritually corrupted practice. By the Kamakura Period, much stricter enforcement and punishments began, with an order from Ise Shrine for a fast for 100 days for eating wild or domestic animals as defined above, while anyone who ate with someone who ate "meat" was required to fast for 21 days, and anyone who ate with someone who ate with someone who consumed "meat" was required to fast for 7 days.[125]

In alternative medicine[]

Although practitioners of alternative medicine promote "cleansing the body" through fasting,[13] the concept of "detoxification“ is marketing myth with few scientific basis for its rationale or efficacy.[126][127]

During the early 20th century, fasting was promoted by alternative health writers such as Hereward Carrington, Edward H. Dewey, Bernarr Macfadden, Frank McCoy, Edward Earle Purinton, Upton Sinclair and Wallace Wattles.[128] All of these writers were either involved in the natural hygiene or new thought movement.[128] Arnold Ehret's pseudoscientific Mucusless Diet Healing System espoused fasting.[129]

Linda Hazzard, a notable quack doctor, put her patients on such strict fasts that some of them died of starvation. She was responsible for the death of more than 40 patients under her care.[130][131]

In 1911, Upton Sinclair authored The Fasting Cure, which made sensational claims of fasting curing practically all diseases, including cancer, syphilis, and tuberculosis.[132][133] Sinclair has been described as "the most credulous of faddists" and his book is considered an example of quackery.[133][134] In 1932, physician Morris Fishbein listed fasting as a fad diet and commented that "prolonged fasting is never necessary and invariably does harm".[135]

While alternative medicine may exaggerate the health benefits of fasting, several studies still show health benefits for animals and humans. Intermittent fasting may lead to improvements in obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancers and neurological disorders. Researchers see the metabolic switch to ketogenesis triggered by fasting periods as one of the reasons for the health benefits.[136]

See also[]

- Angus Barbieri's fast

- Anorexia mirabilis

- Anorexia nervosa

- Asceticism

- Black Fast

- Body fat

- Break fast

- Calorie restriction

- Fasting in Jainism

- Force-feeding

- Fruitarianism

- Gastroenteritis

- Religious intolerance

- Superstition

- Hunger strike

- Inedia

- Intermittent fasting

- Juice fasting

- List of diets

- List of fasting advocates

- List of ineffective cancer treatments

- Overweight

- Poustinia

- Protein-sparing modified fast

- Santhara

- Simple living

- Starvation

- Starvation response

- Taboo food and drink

- Vegetarianism and religion

- Weight loss

References[]

- ^ "Do You Need to Starve Before Surgery? – ABC News". Abcnews.go.com. 25 March 2009. Archived from the original on 8 February 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ^ Norman, Dr (17 April 2003). "Fasting before surgery – Health & Wellbeing". Abc.net.au. Archived from the original on 29 May 2010. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ^ "Anesthesia Information (full edition) | From Yes They're Fake!". Yestheyrefake.net. 1 January 1994. Archived from the original on 12 November 2010. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ^ "Lowering High TRIGLYCERIDES and Raising HDL Naturally – Full of Health Inc". Reducetriglycerides.com. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ^ Fond, G; MacGregor, A; Leboyer, M; Michalsen, A (2013). "Fasting in mood disorders: Neurobiology and effectiveness. A review of the literature". Psychiatry Research. 209 (3): 253–8. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2012.12.018. PMID 23332541. S2CID 39700065. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Whitney, Eleanor Noss; Rolfes, Sharon Rady (27 July 2012). Understanding Nutrition. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1133587521. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- ^ Shils, Maurice Edward; Shike, Moshe (2006). Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781741330. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- ^ Anton, Stephen D; Moehl, Keelin; Donahoo, William T; Marosi, Krisztina; Lee, Stephanie A; Mainous, Arch G; Leeuwenburgh, Christiaan; Mattson, Mark P (2017). "Flipping the Metabolic Switch: Understanding and Applying the Health Benefits of Fasting". Obesity. 26 (2): 254–268. doi:10.1002/oby.22065. PMC 5783752. PMID 29086496.

- ^ Moore, Jimmy; Fung, Jason (2016). The Complete Guide to Fasting: Heal Your Body Through Intermittent, Alternate-Day, and Extended Fasting. Simon and Schuster. p. 232. ISBN 9781628600018. Archived from the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ McCue, Marshall D. (2012). Comparative Physiology of Fasting, Starvation, and Food Limitation. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 15. ISBN 9783642290565. Archived from the original on 1 January 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ Johnstone, A (May 2015). "Fasting for weight loss: an effective strategy or latest dieting trend?". International Journal of Obesity (Review). 39 (5): 727–33. doi:10.1038/ijo.2014.214. PMID 25540982. S2CID 24033290.

- ^ Ahmed, W; Flynn, MA; Alpert, MA (April 2001). "Cardiovascular complications of weight reduction diets". The American Journal of the Medical Sciences (Review). 321 (4): 280–4. doi:10.1097/00000441-200104000-00007. PMID 11307868.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Russell, Sharman Apt; Russell, Sharman (1 August 2008). Hunger: An Unnatural History. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0786722396. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- ^ Leonhardt, David (2013). Nine Habits of Happiness. DoctorZed Publishing. ISBN 9780980625998. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- ^ "Vegetarian Times". Active Interest Media, Inc. 1 October 1985. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Garcia, M. (2007) The Gospel of Cesar Chavez: My Faith in Action Sheed & Ward Publishing p. 103

- ^ Harinarayanan, A. (1986). "GANDHI'S FASTS : AN ANALYSIS (Summary)". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 47: 696–698. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44141630.

- ^ ON THIS DAY 1981: Violence erupts at Irish hunger strike protest Archived 17 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News

- ^ Shaw, R. (2008)Beyond the Fields: Cesar Chavez, the UFW, and the struggle for justice in the 21st century University of California Press, p.92

- ^ Espinosa, G. Garcia, M Mexican American Religions:Spirituality activism and culture(2008) Duke University Press, p 108

- ^ Shaw, R. (2008)Beyond the Fields: Cesar Chavez, the UFW, and the struggle for justice in the 21st century University of California Press, p.93

- ^ Shohret Hoshur, Joshua Lipes (14 May 2020). "Residents of Uyghur-Majority County in Xinjiang Ordered to Report Others Fasting During Ramadan". Radio Free Asia. Translated by Elise Anderson, Alim Seytoff. Retrieved 17 May 2020.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ "History of the Fast". Archived from the original on 27 December 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ^ https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/bc/content/ldsorg/topics/fasting-and-fast-offerings/PD60001350_TMP_2016%20LeadMtg_The%20Law%20of%20the%20Fast_9-15-16%20KW.pdf

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Smith, Peter (2000). "fasting". A concise encyclopedia of the Baháʼí Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. pp. 157. ISBN 978-1-85168-184-6.

- ^ Effendi, Shoghi (1973). Directives from the Guardian. Hawaii Baháʼí Publishing Trust. p. 28. Archived from the original on 6 July 2008. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- ^ "The Buddhist Monk's Discipline: Some Points Explained for Laypeople". Accesstoinsight.org. 23 August 2010. Archived from the original on 2 December 2010. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ^ "Kitagiri Sutta-Majjhima Nikaya". Urbandharma.org. Archived from the original on 30 November 2010. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ Lee, Yujin; Krawinkel, Michael (2009). "Body composition and nutrient intake of Buddhist vegetarians". Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 18 (2): 265–271. ISSN 0964-7058. PMID 19713187.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Harderwijk, Rudy (6 February 2011). "The Eight Mahayana Precepts". Viewonbuddhism.org. Archived from the original on 27 January 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ For further information, see The Way to Buddhahood: Instructions from a Modern Chinese Master by Venerable Yin-shun.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Nyung Ne". Drepung.org. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ "Nyungne Retreat with Lama Dudjom Dorjee". Ktcdallas.org. Archived from the original on 26 December 2010. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ Randi Fredricks (20 December 2012). Fasting: An Exceptional Human Experience. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4817-2379-4. Archived from the original on 7 February 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ Bhikkhu, Thanissaro (5 June 2010). "Questions of Skill". Access to Insight. John T. Bullitt. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

Each time you're about to act, ask yourself: "This action that I want to do: would it lead to self-harm, to the harm of others, or to both? Is it an unskillful action, with painful consequences, painful results?" If you foresee harm, don't follow through with it.

- ^ Harris, Elizabeth J. (7 June 2010). "Violence and Disruption in Society: A Study of the Early Buddhist Texts". Access to Insight. John T. Bullitt. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

If you, Rahula, are desirous of doing a deed with the body, you should reflect on the deed with the body, thus: "That deed which I am desirous of doing with the body is a deed of the body that might conduce to the harm of self and that might conduce to the harm of others and that might conduce to the harm of both; this deed of body is unskilled (akusala), its yield is anguish, its result is anguish.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Gavitt, Loren Nichols (1991). Saint Augustine's Prayer Book. Holy Cross Publications. Archived from the original on 7 February 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ David Grumett and Rachel Muers, Theology on the Menu: Asceticism, Meat and Christian Diet (Routledge, 2010).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Chisholm, Hugh (1911). The Encyclopaedia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information. Encyclopaedia Britannica. p. 428. Archived from the original on 1 January 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

The Lenten fast was retained at the Reformation in some of the reformed Churches, and is still observed in the Anglican and Lutheran communions.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gassmann, Günther; Oldenburg, Mark W. (10 October 2011). Historical Dictionary of Lutheranism. Scarecrow Press. p. 229. ISBN 9780810874824.

In many Lutheran churches, the Sundays during the Lenten season are called by the first word of their respective Latin Introitus (with the exception of Palm/Passion Sunday): Invocavit, Reminiscere, Oculi, Laetare, and Judica. Many Lutheran church orders of the 16th century retained the observation of the Lenten fast, and Lutherans have observed this season with a serene, earnest attitude. Special days of eucharistic communion were set aside on Maundy Thursday and Good Friday.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ripley, George; Dana, Charles Anderson (1883). The American Cyclopaedia: A Popular Dictionary for General Knowledge. D. Appleton and Company. p. 101. Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

The Protestant Episcopal, Lutheran, and Reformed churches, as well as many Methodists, observe the day by fasting and special services.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hatch, Jane M. (1978). The American Book of Days. Wilson. p. 163. ISBN 9780824205935.

Special religious services are held on Ash Wednesday by the Church of England, and in the United States by Episcopal, Lutheran, and some other Protestant churches. The Episcopal Church prescribes no rules concerning fasting on Ash Wednesday, which is carried out according to members' personal wishes; however, it recommends a measure of fasting and abstinence as a suitable means of marking the day with proper devotion. Among Lutherans as well, there are no set rules for fasting, although some local congregations may advocate this form of penitence in varying degrees.

- ^ Stravinskas, Peter M. J.; Shaw, Russell B. (1 September 1998). Our Sunday Visitor's Catholic Encyclopedia. Our Sunday Visitor. ISBN 9780879736699.

The so-called black fast refers to a day or days of penance on which only one meal is allowed, and that in the evening. The prescription of this type of fast not only forbids the partaking of meats but also of all dairy products, such as eggs, butter, cheese and milk. Wine and other alcoholic beverages are forbidden as well. In short, only bread, water and vegetables form part of the diet for one following such a fast.

- ^ Cléir, Síle de (5 October 2017). Popular Catholicism in 20th-Century Ireland: Locality, Identity and Culture. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 101. ISBN 9781350020603.

Catherine Bell outlines the details of fasting and abstinence in a historical context, stating that the Advent fast was usually less severe than that carried out in Lent, which originally involved just one meal a day, not to be eaten until after sunset.

- ^ Guéranger, Prosper; Fromage, Lucien (1912). The Liturgical Year: Lent. Burns, Oates & Washbourne. p. 8.

St. Benedict's rule prescribed a great many fasts, over and above the ecclesiastical fast of Lent; but it made this great distinction between the two: that whilst Lent obliged the monks, as well as the rest of the faithful, to abstain from food till sunset, these monastic fasts allowed the repast to be taken at the hour of None.

- ^ "Some Christians observe Lenten fast the Islamic way". Union of Catholic Asian News. 27 February 2002. Archived from the original on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ "The Lighthouse" (PDF). Christ the Savior Orthodox Church. 2018. p. 3.

- ^ "Code of Canon Law - IntraText". www.vatican.va. Archived from the original on 15 November 2011. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- ^ "Fast & Abstinence".

- ^ "Rules for fast and abstinence". SSPX. 3 December 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "The Church Laws of Fast and Abstinence". Saint Theresa's Roman Catholic Church. 17 November 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ "Lesson 28 — Holy Communion". Congregation of Mary Immaculate Queen. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ Buchanan, Colin (27 February 2006). Historical Dictionary of Anglicanism. Scarecrow Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-8108-6506-8.

In the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, there is a list of "Days of Fasting, or Abstinence," consisting of the 40 days of Lent, the ember days, the three rogation days (the Monday to Wednesday following the Sunday after Ascension Day), and all Fridays in the year (except Christmas, if it falls on a Friday).

- ^ Daniel Cobb, Derek Olsen (ed.). Saint Augustine's Prayer Book. pp. 4–5.

- ^ Concerning Fasting on Wednesday and Friday. Orthodox Christian Information Center. Accessed 2010-10-08.

- ^ Menzel, Konstantinos (14 April 2014). "Abstaining From Sex Is Part of Fasting". Greek Reporter. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Kallistos (Ware), Bishop; Mary, Mother (1978). The Lenten Triodion. South Canaan PA: St. Tikhon's Seminary Press (published 2002). pp. 35ff. ISBN 978-1-878997-51-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kallistos (Ware), Bishop (1964). The Orthodox Church. London: Penguin Books. pp. 75–77, 306ff. ISBN 978-0-14-020592-3.

- ^ Gregory Palamas, Letter 234, I (Migne, Patrologia Graecae, 1361C)

- ^ "Old Orthodox Prayer Book" (2nd ed.). Erie PA: Russian Orthodox Church of the Nativity of Christ (Old Rite). 2001: 349ff. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ "August 1991". Stjamesok.org. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ^ "Days on which it is forbidden to fast - Islam Question & Answer". islamqa.info. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ "John Wesley and Spiritual Disciplines-- The Works of Piety". The United Methodist Church. 2012. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Beard, Steve (30 January 2012). "The spiritual discipline of fasting". Good News Magazine. United Methodist Church.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Crowther, Jonathan (1815). A Portraiture of Methodism: Or, The History of the Wesleyan Methodists. T. Blanshard. pp. 251, 257.

- ^ McKnight, Scot (2010). Fasting: The Ancient Practices. Thomas Nelson. p. 88. ISBN 9781418576134.

John Wesley, in his Journal, wrote on Friday, August 17, 1739, that "many of our society met, as we had appointed, at one in the afternoon and agreed that all members of our society should obey the Church to which we belong by observing 'all Fridays in the year' as 'days of fasting and abstinence.'

- ^ Synan, Vinson (25 August 1997). The Holiness-Pentecostal Tradition: Charismatic Movements in the Twentieth Century. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 24. ISBN 9780802841032.

- ^ Smith, Larry D. (September 2008). "Progressive Sanctification" (PDF). God's Revivalist and Bible Advocate. 120 (6). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

Principles which underlie our Wesleyan/holiness heritage include such commitments as unquestioned scriptural authority; classical orthodox theology; identity with the one holy and apostolic church; warmhearted evangelical experience; love perfected in sanctifying grace; careful, disciplined living; structured spiritual formation, fidelity to the means of grace; and responsible witness both in public and in private—all of which converge in holiness of heart and life, which for us Methodists will always be the “central idea of Christianity.” These are bedrock essentials, and without them we shall have no heritage at all. Though we may neglect them, these principles never change. But our prudentials often do. Granted, some of these are so basic to our DNA that to give them up would be to alter the character of our movement. John Wesley, for example, believed that the prudentials of early Methodism were so necessary to guard its principles that to lose the first would be also to lose the second. His immediate followers should have listened to his caution, as should we. For throughout our history, foolish men have often imperiled our treasure by their brutal assault against the walls which our founders raised to contain them. Having said this, we must add that we have had many other prudentials less significant to our common life which have come and gone throughout our history. For instance, weekly class meetings, quarterly love feasts, and Friday fast days were once practiced universally among us, as was the appointment of circuit-riding ministers assisted by “exhorters” and “local preachers.”

- ^ Epps, David (20 February 2018). "Facts about fasting". The Citizen. Archived from the original on 17 March 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

In Methodism, fasting is considered one of the “Works of Piety.” The Discipline of the Wesleyan Methodist Church required Methodists to fast on certain days. Historically, Methodist clergy are required to fast on Wednesdays, in remembrance of the betrayal of Christ, and on Fridays, in remembrance of His crucifixion and death.

- ^ Earley, Dave (2012). Pastoral Leadership Is...: How to Shepherd God's People with Passion and Confidence. B&H Publishing Group. p. 103. ISBN 9781433673849.

- ^ Abraham, William J.; Kirby, James E. (24 September 2009). The Oxford Handbook of Methodist Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 257–. ISBN 978-0-19-160743-1.

- ^ "What does The United Methodist Church say about fasting?". The United Methodist Church. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ^ Chavez, Kathrin (2010). "Lent: A Time to Fast and Pray". The United Methodist Church. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gentilcore, David (19 November 2015). Food and Health in Early Modern Europe: Diet, Medicine and Society, 1450-1800. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 125. ISBN 9781472528421.

- ^ Albala, Ken. 2003. Food in early modern Europe. P.200

- ^ [1] Archived 2 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ What is the holiest season of the Church Year? Archived 9 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 3 February 2010. Archived copy at the Internet Archive

- ^ Pfatteicher, Philip H. (1990). Commentary on the Lutheran Book of Worship: Lutheran Liturgy in Its Ecumenical Context. Augsburg Fortress Publishers. pp. 223–244, 260. ISBN 9780800603922.

The Good Friday fast became the principal fast in the calendar, and even after the Reformation in Germany many Lutherans who observed no other fast scrupulously kept Good Friday with strict fasting.

- ^ Jacobs, Henry Eyster; Haas, John Augustus William (1899). The Lutheran Cyclopedia. Scribner. p. 110. Archived from the original on 9 April 2010. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

By many Lutherans Good Friday is observed as a strict fast. The lessons on Ash Wednesday emphasize the proper idea of the fast. The Sundays in Lent receive their names from the first words of their Introits in the Latin service, Invocavit, Reminiscere, Oculi, Lcetare, Judica.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Weitzel, Thomas L. (1978). "A Handbook for the Discipline of Lent" (PDF). Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 March 2018. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ An explanation of Luther's Small Catechism: The Sacrament of the Eucharist, section IV: Who receives the Sacrament worthily? (LCMS). Retrieved 15 October 2009.