Fielding (cricket)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2014) |

Fielding in the sport of cricket is the action of fielders in collecting the ball after it is struck by the striking batter, to limit the number of runs that the striker scores and/or to get a batter out by either catching a hit ball before it bounces, or by running either batter out before they can complete the run they are currently attempting. There are a number of recognised fielding positions, and they can be categorised into the offside and leg side of the field. Fielding also involves preventing the ball from going to or over the edge of the field (which would result in runs being scored by the batting team in the form of a boundary).

A fielder or fieldsman may field the ball with any part of his body. However, if while the ball is in play he wilfully fields it otherwise (e.g. by using his hat), the ball becomes dead and five penalty runs are awarded to the batting side, unless the ball previously struck a batter not attempting to hit or avoid the ball. Most of the rules covering fielders are in Law 28 of the Laws of cricket.

Fake fielding is the action caused by a fielder when he makes movements of some of his body parts as if he were fielding only to confuse batters into making mistakes. It is now a punishable offence under the ICC rules.[1]

Fielding position names and locations[]

There are 11 players in a team: one is the bowler and another is the wicket-keeper, so only nine other fielding positions can be occupied at any time. Where fielders are positioned is a tactical decision made by the captain of the fielding team. The captain (usually in consultation with the bowler and sometimes other members of the team) may move players between fielding positions at any time except when a bowler is in the act of bowling to a batter, though there are exceptions for fielders moving in anticipation of the ball being hit to a particular area.[2]

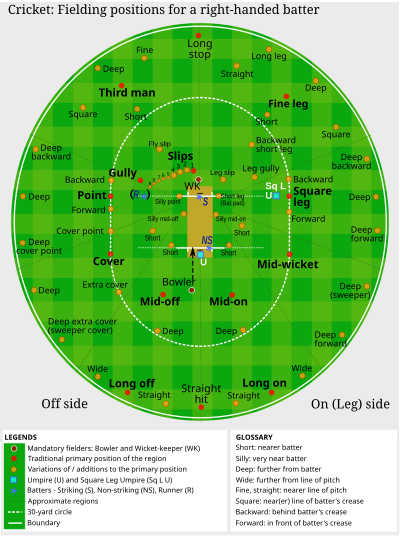

There are a number of named basic fielding positions, some of which are employed very commonly and others that are used less often. However, these positions are neither fixed nor precisely defined, and fielders can be placed in positions that differ from the basic positions. The nomenclature of the positions is somewhat esoteric, but roughly follows a system of polar coordinates – one word (leg, cover, mid-wicket) specifies the angle from the batter, and is sometimes preceded by an adjective describing the distance from the batter (silly, short, deep or long). Words such as "backward", "forward", or "square" can further indicate the angle.

The image shows the location of most of the named fielding positions based on a right-handed batter. The area to the left of a right-handed batter (from the batter's point of view – facing the bowler) is called the leg side or on side, while that to the right is the off side. If the batter is left-handed, the leg and off sides are reversed and the fielding positions are a mirror image of those shown.[3]

Catching positions[]

Some fielding positions are used offensively. That is, players are put there with the main aim being to catch out the batter rather than to stop or slow down the scoring of runs. These positions include Slip (often there are multiple slips next to each other, designated First slip, Second slip, Third slip, etc., numbered outwards from the wicket-keeper – collectively known as the slip cordon) meant to catch balls that just edge off the bat; Gully; Fly slip; Leg slip; Leg gully; the short and silly positions. Short leg, also known as bat pad, is a position specifically intended to catch balls that unintentionally strike the bat and leg pad, and thus end up only a metre or two to the leg side.[4]

Other positions[]

- Wicket-keeper

- Long stop, who stands behind the wicket-keeper towards the boundary (usually when a wicket-keeper is believed to be inept; the position is almost never seen in professional cricket). It was an important position in the early days of cricket, but with the development of wicket-keeping techniques from the 1880s, notably at first by the Australian wicket-keeper Jack Blackham, it became obsolete at the highest levels of the game.[5] The position is sometimes euphemistically referred to as very fine leg.[6]

- Sweeper, an alternative name for deep cover, deep extra cover or deep midwicket (that is, near the boundary on the off side or the on side), usually defensive and intended to prevent a four being scored.

- Cow corner, an informal jocular term for the position on the boundary between deep midwicket and long on.

- on the 45. A position on the leg side 45° behind square, defending the single. An alternative description for backward short leg or short fine leg.

Also the bowler, after delivering the ball, must avoid running on the pitch so usually ends up fielding near silly mid on or silly mid off, but somewhat closer to the pitch.

Modifiers[]

- Saving one or On the single

- As close as the fielder needs to be to prevent the batters from running a quick single, normally about 15–20 yards (14–18 m) from the wicket.

- Saving two

- As close as the fielder needs to be to prevent the batters from running two runs, normally about 50–60 yards (46–55 m) from the wicket.

- Right on

- Literally, right on the boundary.

- Deep, long

- Farther away from the batter.

- Short

- Closer to the batter.

- Silly

- Very close to the batter, so-called because of the perceived danger of doing so.[7]

- Square

- Somewhere along an imaginary extension of the popping crease.

- Fine

- Closer to an extension of an imaginary line along the middle of the pitch bisecting the stumps, when describing a fielder behind square.

- Straight

- Closer to an extension of an imaginary line along the middle of the pitch bisecting the stumps, when describing a fielder in front of square.

- Wide

- Further from an extension of an imaginary line along the middle of the pitch bisecting the stumps.

- Forward

- In front of square; further towards the end occupied by the bowler and further away from the end occupied by the batter on strike.

- Backward

- Behind square; further towards the end occupied by the batter on strike and further away from the end occupied by the bowler.

Additionally, commentators or spectators discussing the details of field placement will often use the terms for descriptive phrases such as "gully is a bit wider than normal" (meaning he is more to the side than normal) or "mid off is standing too deep, he should come in shorter" (meaning he is too far away and should be positioned closer to the batter).

Restrictions on field placement[]

Fielders may be placed anywhere on the field, subject to the following rules. At the time the ball is bowled:

- No fielder may be standing on or with any part of his body over the pitch (the central strip of the playing area between the wickets). If his body casts a shadow over the pitch, the shadow must not move until after the batter has played (or had the opportunity to play) at the ball.

- There may be no more than two fielders, other than the wicket-keeper, standing in the quadrant of the field behind square leg. See Bodyline for details on one reason this rule exists.

- In some one-day matches:

- During designated overs of an innings (see Powerplay), there may be no more than two fielders standing outside an oval line marked on the field, being semicircles centred on the middle stump of each wicket of radius 30 yards (27 m), joined by straight lines parallel to the pitch. This is known as the fielding circle.

- For overs no. 11–40 (powerplay 2), no more than four fielders should be outside the 30-yard circle.

- For overs no. 41–50 (powerplay 3) maximum of five fielders are allowed to be outside the 30-yard circle.

- The restriction for one-day cricket is designed to prevent the fielding team from setting extremely defensive fields and concentrating solely on preventing the batting team from scoring runs.

If any of these rules is violated, an umpire will call the delivery a no-ball. Additionally a player may not make any significant movement after the ball comes into play and before the ball reaches the striker. If this happens, an umpire will call and signal 'dead ball'. For close fielders, anything other than minor adjustments to stance or position in relation to the striker is significant. In the outfield, fielders may move in towards the striker or striker's wicket; indeed, they usually do. However, anything other than slight movement off line or away from the striker is to be considered significant.

Tactics of field placement[]

This section does not cite any sources. (October 2017) |

With only nine fielders (in addition to the bowler and wicket-keeper), there are not enough to cover every part of the field simultaneously. The captain of the fielding team must decide which fielding positions to use, and which to leave vacant. The placement of fielders is one of the major tactical considerations for the fielding captain.

Attacking and defending[]

This section does not cite any sources. (January 2018) |

The main decision for a fielding captain is to strike a balance between setting an attacking field and a defensive field. An attacking field is one in which fielders are positioned in such a way that they are likely to take catches, and thus likely to get the batter out. Such a field generally involves having many fielders close to the batter. For a pace bowler, an attacking field will usually include multiple slips (termed a cordon) and a gully; these are common positions for catching miss-hit shots. For a spin bowler, attacking positions include one or two slips, short leg or silly point.

A defensive field is one in which most of the field is covered by a fielder; the batter will therefore find it difficult to score runs. This generally involves having many fielders far from the batter and in front of them, in the positions where they are most likely to hit the ball. Defensive fields generally have multiple fielders stationed close to the boundary rope to prevent fours being scored, and others close to the circle, where they can prevent singles.

Many elements govern the decisions on field placements, including: the tactical situation in the match; which bowler is bowling; how long the batter has been in; the wear on the ball; the state of the wicket; the light and weather conditions; or the time remaining until the next interval in play.

Some general principles:

- Attack…

-

- … new batters

- A batter early in their innings is less familiar with the conditions, the bowlers etc. and is more likely to make a miscalculated or rash shot, so it pays to have catching fielders ready.

- … with the new ball

- Fast bowlers get more swing and bounce with a less worn ball. Fielding teams generally use their best bowlers when the ball is new. Batting is consequently more difficult and more attacking fields can be used.

- … when returning from a break in play

- Batters must settle into a batting rhythm again when resuming play after a break (due to a scheduled interval betweens sessions, bad weather etc.). They are more likely to make mistakes whilst doing so.

- … with quality bowlers

- A team's best bowlers tend to deliver the most difficult balls to score from, and induce the most chances for a catch, so they get the most benefit from an attacking field.

- … when the pitch helps the bowler

- A moist pitch produces unpredictable bounce and seam-movement of the ball; a dry, crumbling pitch helps spin bowlers get increased and unpredictable spin; and damp, overcast conditions help swing bowlers. All three situations can lead to catches flying to close attacking fielders.

- … when the batting team is under pressure

- If the batting team is doing poorly or has low morale, increase the pressure by attacking with the field.

- … when the batting side are playing for a draw

- If the batting team is a long way behind in a timed game and there is not much time left, it becomes more important to bowl out the batters and secure a victory, than to control runs which would probably lead to a draw.

- Defend…

-

- … when batters are settled in

- It is difficult to get batters out when they have been batting for a long time and are comfortable with the bowling. Defending will slow the run scoring rate, which can frustrate the batter and force them into playing a rash shot.

- … when the batting team needs to score runs quickly

- In situations where the batting team must score quickly in order to win or press an advantage (e.g. the "death overs" at the end of a limited-over innings), slowing down the scoring becomes more important than trying to dismiss the batters.

- … when the batting team is scoring quickly

- If the batters are scoring rapidly, it is unlikely they are offering many chances to get them out, so reduce the run scoring rate.

- … when the ball and pitch offer no help to the bowlers

- If there is no movement of the ball and the batters can hit it comfortably every time, there is little point in having many close catching fielders as few chances will be available.

- … when using weak bowlers

- If a relatively poor bowler must bowl for any reason, the potential damage can be limited by defending against run scoring.

Off- and leg-side fields[]

Another consideration when setting a field is how many fielders to have on each side of the pitch. With nine fielders to place, the division must necessarily be unequal, but the degree of inequality varies.

When describing a field setting, the numbers of fielders on the off side and leg side are often abbreviated into a shortened form, with the off side number quoted first. For example, a 5–4 field means 5 fielders on the off side and 4 on the leg side.

Usually, most fielders are placed on the off side. This is because most bowlers tend to concentrate the line of their deliveries on or outside the off stump, so most shots are hit into the off side.

When attacking, there may be 3 or 4 slips and 1 or 2 gullies, potentially using up to six fielders in that region alone. This would typically be accompanied by a mid off, mid on, and fine leg, making it a 7–2 field. Although there are only two fielders on the leg side, they should get relatively little work as long as the bowlers maintain a line outside off stump. This type of field leaves large gaps in front of the wicket, and is used to entice the batters to attack there, with the hope that they make a misjudgment and edge the ball to the catchers waiting behind them.

As fields get progressively more defensive, fielders will move out of the slip and gully area to cover more of the field, leading to 6–3 and 5–4 fields.

If a bowler, usually a leg spin bowler, decides to attack the batter's legs in an attempt to force a stumping, bowl him behind his legs, or induce a catch on the leg side, the field may stack 4–5 towards the leg side. It is unusual to see more than 5 fielders on the leg side, because of the restriction that there must be no more than two fielders placed behind square leg.

Sometimes a spinner will bowl leg theory and have seven fielders on the leg side, and will bowl significantly wide of the leg stump to prevent scoring. Often the ball is so wide that the batter cannot hit the ball straight of mid-on while standing still, and cannot hit to the off side unless they try unorthodox and risky shots such as a reverse sweep or pull, or switch their handedness. The batter can back away to the leg side to hit through the off side, but can expose their stumps in doing so.

The reverse tactic can be used, by fast and slow bowlers alike, by placing seven or eight fielders on the off side and bowling far outside off stump. The batter can safely allow the ball to pass without fear of it hitting the stumps, but will not score. If they want to score they will have to try and risk an edge to a wide ball and hit through the packed off side, or trying and drag the ball from far outside the stumps to the sparsely-populated leg side.

Another attacking placement on the leg side is the leg side trap, which involves placing fielders near the boundary at deep square and backward square leg and bowling bouncers to try to induce the batter to hook the ball into the air. For slower bowlers, the leg trap fieldsmen tend to be placed within 10–15 m from the bat behind square, to catch leg glances and sweeps.

Protective equipment[]

No member of the fielding side other than the wicket-keeper may wear gloves or external leg guards, though fielders (in particular players fielding near to the bat) may also wear shin protectors, groin protectors ('boxes') and chest protectors beneath their clothing. Apart from the wicket-keeper, protection for the hand or fingers may be worn only with the consent of the umpires.[8]

Fielders are permitted to wear a helmet and face guard. This is usually employed in a position such as silly point or silly mid-wicket, where proximity to the batter gives little time to avoid a shot directly at their head. If the helmet is only being used for overs from one end, it will be placed behind the wicketkeeper when not in use. Some grounds have purpose-built temporary storage for the helmet, shin pads etc., in the form of a cavity beneath the field, accessed through a hatch about 1 m (3 ft) across flush with the grass. 5 penalty runs are awarded to the batting side should the ball touch a fielder's headgear whilst it is not being worn, unless the ball previously struck a batter not attempting to hit or avoid the ball. This rule was introduced in the 19th century to prevent the unfair practice of a fielder using a hat (often a top hat) to take a catch.[8]

As cricket balls are hard and can travel at high speeds off the bat, protective equipment is recommended to prevent injury. There have been a few recorded deaths in cricket,[9] but they are extremely rare, and not always related to fielding.[10]

Fielding skills[]

Fielding in cricket requires a range of skills.

Close catchers require the ability to be able to take quick reaction catches with a high degree of consistency. This can require considerable efforts of concentration as a catcher may only be required to take one catch in an entire game, but his success in taking that catch may have a considerable effect on the outcome of the match.

Infielders field between 20 and 40 yards away from the batter. The ball will often be hit at them extremely hard, and they require excellent athleticism as well as courage in stopping it from passing them. Infield catches range from simple, slow moving chances known as "dollies" to hard hit balls that require a spectacular diving catch. Finally, infielders are the main source of run outs in a game of cricket, and their ability to get to the ball quickly, throw it straight and hard and make a direct hit on the stumps is an important skill.

Outfielders field furthest from the bat, typically right on the boundary edge. Their main role is to prevent the ball from going over the boundary and scoring four or six runs. They need good footspeed to be able to get around the field quickly, and a strong arm to be able to make the 50–80-yard throw. Outfielders also often have to catch high hit balls that go over the infield.

Fielding specialities[]

This section does not cite any sources. (October 2017) |

Many cricketers are particularly adept in one fielding position and will usually be found there:

- Slips and bat pad require fast reactions, an ability to anticipate the trajectory of the ball as soon as it takes the edge, and intense concentration. Most top slip fielders tend to be top-order batters, as these are both skills that require excellent hand–eye coordination. Wicket-keepers and Bat-pad tend to be amongst the shortest players of the team.

- Pace bowlers will often be found fielding in the third man, fine leg and deep backward square positions during the overs between those they are bowling. These positions mean that they are at the correct end for their bowling over. They should see relatively little fielding action with plenty of time to react, allowing them to rest between overs.[11] They also usually have an ability to throw the ball long distances accurately.

- Players noted for their agility, acceleration, ground diving and throwing accuracy will often field in the infield positions such as point, cover and mid-wicket.

However, players are rarely selected purely because of their fielding skills, and all players are expected to win their place in the team as either a specialist batter or bowler (or both). This even applies to wicket keepers, who are generally expected to be competent middle-order batters (see Wicket-keeper-batter, where more than one wicketkeeper can be selected to play as an on-field substitution). Some wicketkeepers may also be called on to bowl, though this is extremely rare.

Throwing a cricket ball[]

There have been many competitions for throwing a cricket ball the furthest distance, particularly in the earlier years of the game. Wisden describes how the record was set around 1882, by one Robert Percival at Durham Sands Racecourse, at 140 yards and two feet (128.7 m). Former Essex all-rounder Ian Pont threw a ball 138 yards (126.19 m) in Cape Town in 1981. There are unconfirmed reports that Jānis Lūsis, the non-cricketer Soviet javelin thrower, who won the Olympic gold medal in 1968, once threw a ball 150 yards.[12]

Specialist fielding coaches[]

The use of specialist fielding coaches has become more prevalent since the turn of the 21st century, following the trend of specialist batting and bowling coaches within professional cricket. According to cricket broadcaster Henry Blofeld, "Dressing rooms were once populated by the team and the twelfth man, one physiotherapist at most, perhaps a selector and the occasional visitor. That was all. Now, apart from the two main coaches, there are 'emergency fielders' galore; you can hardly see yourself for batting, bowling, fielding coaches, psychoanalysts and statistical wizards[,] and a whole army of physiotherapists".[13] Baseball fielding coaches have been sought out for this purpose before.[14]

See also[]

Other sports

- Fielding (baseball)

References[]

- ^ "Men's ODI Match Clause 41: Unfair Play". www.icc-cricket.com. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ "MCC revises fielder movement Law | ESPNcricinfo.com". www.espncricinfo.com. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ "All Cricket Fielding Positions explained to better understand the commentary next time". Chase Your Sport. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ Rakesh (19 August 2018). "Cricket Fielding Positions and Field Placements". Sportslibro.com. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ "Cricket: The Long Stop". The Maitland Daily Mercury: 9. 18 February 1928.

- ^ Bluffer's Guide to Cricket Archived 23 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 'silly, adj., n., and adv' (definition 5d), Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Law 28 – The fielder". MCC. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ Williamson, Martin (14 August 2010). "The tragic death of Raman Lamba". ESPN Cricinfo. Retrieved 12 October 2020. On 20 February 1998, Raman Lamba fielding at forward short-leg without a helmet on, was struck on the forehead.

- ^ On 25 November 2014, Phil Hughes batting with a helmet on, suffered a blow to the back of the neck.

- ^ "PitchVision - Live Local Matches | Tips & Techniques | Articles & Podcasts". PitchVision - Advance Cricket Technology | Cricket Analytics. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ Wisden 2012, p. 1383.

- ^ Henry Blofeld, My A-Z of Cricket: A Personal Celebration of our Glorious Game (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2019). ISBN 1529378508, 9781529378504. See also Naresh Sharma, Match Fixing, Hang the Culprits, Indian Cricket: Lacklustre Performance and Lack of a Killer Instinct (Delhi: Minerva Press, 2001), 215. ISBN 8176622265, 9788176622264

- ^ jspasaro. "Mike Young fires stern parting words at Darren Lehmann". Sunshine Coast Daily. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

External links[]

- Fielding (cricket)

- Cricket terminology

- Cricket captaincy and tactics

- Positions (team sports)