First Aliyah

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2020) |

| Part of a series on |

| Aliyah |

|---|

|

| Jewish return to the Land of Israel |

| Concepts |

| Pre-Modern Aliyah |

| Aliyah in modern times |

| Absorption |

| Organizations |

| Related topics |

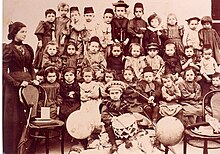

The First Aliyah (Hebrew: העלייה הראשונה, HaAliyah HaRishona), also known as the agriculture Aliyah, was a major wave of Jewish immigration (aliyah) to Ottoman Palestine between 1881 and 1903.[1][2] Jews who migrated in this wave came mostly from Eastern Europe and from Yemen. An estimated 25,000[3]–35,000[4] Jews immigrated. Many of the European Jewish immigrants during the late 19th-early 20th century period gave up after a few months and went back to their country of origin, often suffering from hunger and disease.[5] Because there had been immigration to Palestine in earlier years as well, use of the term "First Aliyah" is controversial.[6]

Nearly all of the Jews from Eastern Europe before that time came from traditional Jewish families. The immigrants that were part of the First Aliyah came more out of a connection to the land of their ancestors.[3][7] Most of these immigrants worked as artisans or in small trade, but many also worked in agriculture. Only some of them came in an organized fashion, with the help of Hovevei Zion, but most of them were unorganized, in their 30s, and had families.[citation needed] Most settlements met with financial difficulties and most of the settlers were not proficient in farming.

The First Aliyah was considered a success through the eyes of some historians since Jews were able to migrate and thrive economically in Palestine.[citation needed] Others may say the First Aliyah was not a success because many of these immigrants did not stay and there was a shortage of funds necessary to sustain the movement.[citation needed]

Only a small minority of the 6,000 who emigrated, about 2%, remained in Ottoman Palestine.[citation needed] The Jewish Virtual Library says of the First Aliyah that nearly half the settlers did not stay in the country.[8]

From Eastern Europe[]

Jewish immigration to Ottoman Palestine from Eastern Europe occurred as part of the mass emigrations of approximately 2.5 million people[9] that took place towards the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. A rapid increase in population had created economic problems that affected Jewish societies in the Pale of Settlement in Russia, Galicia, and Romania.[7]

Persecution of Jews in Russia was also a factor. In 1881, Tsar Alexander II of Russia was assassinated, and the authorities blamed the Jews for the assassination. Consequently, in addition to the May Laws, major anti-Jewish pogroms swept the Pale of Settlement. A movement called Hibbat Zion (love of Zion) spread across the Pale (helped by Leon Pinsker's pamphlet Auto-Emancipation), as did the similar Bilu movement. Both movements encouraged Jews to emigrate to Ottoman Palestine.

From Yemen[]

The first group of immigrants from Yemen came approximately seven months before most of the Eastern European Jews arrived in Palestine.

Due to the changes in the Ottoman Empire, citizens could move more freely, and in 1869, travel was improved with the opening of the Suez Canal, which reduced the travel time from Yemen to Ottoman Syria. Certain Yemenite Jews interpreted these changes and the new developments in the "Holy Land" as heavenly signs that the time of redemption was near. By settling in Ottoman Syria, they would play a part in what they believed could precipitate the anticipated messianic era. Emigration from Yemen to the Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem (Ottoman Syria) began in early 1881 and continued almost without interruption until 1914. It was during this time that about 10% of the Yemenite Jews left. From 1881 to 1882, a few hundred Jews left Sanaa and several nearby settlements. This wave was followed by other Jews from central Yemen who continued to move into Ottoman Syrian provinces until 1914. The majority of these groups moved into Jerusalem and Jaffa. In 1884, some families settled into a new-built neighborhood called Yemenite Village Kfar Hashiloach (Hebrew: כפר השילוח) in the Jerusalem district of Silwan, and built the Old Yemenite Synagogue.[10][11]

Before World War I, there was another wave that began in 1906 and continued until 1914. Hundreds of Yemenite Jews made their way to Ottoman Syria and chose to settle in the agricultural settlements. It was after these movements that the World Zionist Organization sent Shmuel Yavne'eli to Yemen to encourage Jews to emigrate to the Land of Israel. Yavne'eli reached Yemen at the beginning of 1911 and returned to Ottoman Syria in April 1912. Due to Yavne'eli's efforts, about 1,000 Jews left central and southern Yemen, with several hundred more arriving before 1914.[12]

History[]

The First Aliyah occurred from 1881 to 1903 and did not go as planned as Zionists ran out of funds.[7] The Rothschild organization rescued the Zionist movement by funding Zionists and by purchasing large settlements and by creating new settlements.[13] At the closure of the first Aliya, the Jews had purchased 350,000 dunams of land.

The first central committee for the settlement was established by a convention of "Unions for the Agricultural Settlement of Israel" () held on January 11, 1882, in Romania. The committee was the first organization to organize group aliyahs, such as the Jewish passenger ships that set sail from Galaţi.[citation needed]

After the first wave in the early 1880s, there was another spike in 1890. The government of Imperial Russia officially approved the activity of Hovevei Zion in 1890. The same year, the "Odessa Committee" began its operation in Jaffa. The purpose of this organization was to absorb immigrants to Ottoman Syria who came as a result of the activities of Hovevei Zion in Russia. Also Russian Jewry's situation deteriorated as the authorities continued to push Jews out of business and trade and Moscow was almost entirely cleansed of Jews.[14] Finally, the financial situation of the settlements from the previous decade improved due to the Baron Edmond James de Rothschild's assistance.

The relationship of the members of the First Aliyah with the Old Yishuv was strained. There were disagreements about economic and ideological issues. Only a few groups from the Old Yishuv sought to take part in the First Aliyah's settlement effort, one such group being the Peace of Jerusalem (Shlom Yerushalayim).[15]

Israeli historian Benny Morris wrote:

But the major cause of tension and violence throughout the period 1882–1914 was not accidents, misunderstandings or the attitudes and behaviors of either side, but objective historical conditions and the conflicting interests and goals of the two populations. The Arabs sought instinctively to retain the Arab and Muslim character of the region and to maintain their position as its rightful inhabitants; the Zionists sought radically to change the status quo, buy as much land as possible, settle on it, and eventually turn an Arab-populated country into a Jewish homeland.

For decades the Zionists tried to camouflage their real aspirations, for fear of angering the authorities and the Arabs. They were, however, certain of their aims and of the means needed to achieve them. Internal correspondence amongst the olim from the very beginning of the Zionist enterprise leaves little room for doubt.[16]

Settlement[]

The First Aliyah laid the cornerstone for Jewish settlement in Israel and created several settlements – Rishon LeZion, Rosh Pinna, Zikhron Ya'akov, Gedera, among others. Immigrants of the First Aliyah also contributed to existing Jewish towns and settlements, notably Petah Tikva. The first neighbourhoods of Tel Aviv (Neve Tzedek and Neve Shalom) were also built by members of the aliyah, although it was not until the Second Aliyah that Tel Aviv was officially founded.

The settlements established by the First Aliyah, known in Hebrew as moshavot are:

- Rishon LeZion (1882)

- Rosh Pinna (1882, taking over and renaming the colony of Gei Oni established in 1878 and down to three families by 1882)

- Zikhron Ya'akov (1882)

- Petah Tikva (1882; reestablished after first attempt in 1878)

- Mazkeret Batya (1883 established as "Ekron")

- Ness Ziona (1883; began as "Nahalat Reuven")

- Yesud HaMa'ala (1883)

- Gedera (1884)

- Bat Shlomo (1889)

- Meir Shfeya (1889)

- Rehovot (1890)

- Mishmar HaYarden (1890)

- Hadera (1891)

- Ein Zeitim (1892)

- Motza (1894)

- Hartuv (1895)

- Metula (1896)

- Be'er Tuvia (1896 reestablished and renamed by Hovevei Zion; first settled in 1887 under the name Castina)

- Bnei Yehuda (1898; not identical with the new Bnei Yehuda, Golan Heights)

- Mahanayim (1898–1912)

- Sejera (1899)

- Mas'ha (1901), renamed Kfar Tavor in 1903

- Yavne'el (1901)

- Menahemia (1901)

- (1903; next to Yavne'el)

- Atlit (1903)

- Giv'at Ada (1903)

- Kfar Saba (1904)

The five ephemeral settlements of the First Aliyah in the Hauran are not included.

Notes[]

- ^ Bernstein, Deborah S. Pioneers and Homemakers: Jewish Women in Pre-State IsraelState University of New York Press, Albany. (1992) p.4

- ^ Scharfstein, Sol, Chronicle of Jewish History: From the Patriarchs to the 21st Century, p.231, KTAV Publishing House (1997), ISBN 0-88125-545-9

- ^ Jump up to: a b "New Aliyah – Modern Zionist Aliyot (1882–1948)". Jewish Agency for Israel. Archived from the original on 2009-06-23. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ^ "The First Aliyah (1882–1903)". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ Joel Brinkley, As Jerusalem Labors to Settle Soviet Jews, Native Israelis Slip Quietly Away, The New York Times, 11 February 1990. Quote: "In the late 19th and early 20th century many of the European Jews who set up religious settlements in Palestine gave up after a few months and returned home, often hungry and diseased.". Accessed 4 May 2020.

- ^ Halpern, Ben (1998). Zionism and the creation of a new society. Reinharz, Jehuda. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 53–54. ISBN 0-585-18273-6. OCLC 44960036.

It is the accepted convention to divide the flow of Jewish immigrants into a series of aliyot (sing., aliyah), or waves of newcomers, each of which made a characteristic contribution to the New Yishuv's developing institutional structure. The final product, the base upon which Israel was founded, is pictured as a stratified deposit of the historic achievements of the successive aliyot from 1881 to 1948. Like most historical generalizations, these too are useful mainly as points of departure. The actual course of events does not follow closely the lines they lay down, but the profile of history is illuminated when one plots the curve of deviations from these initial assumptions. The First Aliyah, from 1881 to 1903, is said to have brought those pioneers who first established Jewish farming villages, the moshavot (sing., moshavah), the mainstay of Israel's private agricultural sector. This observation merely provides a skeletal (and incomplete) framework rather than a full description of Israel's institutional development during that period. From 1881 to 1903, Palestine Jewry is estimated to have increased from about 22,000 or 24,000 to about 47,000 or 50,000, mainly because of immigration in 1881–84 and 1890–91. Of the 20,000 to 30,000 newcomers, only 3,000 settled in the new moshavot, the characteristic achievement of the First Aliyah. On the other hand, Jerusalem, the stronghold of the established institutions of the Old Yishuv, increased from 14,000 to 28,000, by far the greater part of whom were undoubtedly absorbed into the traditionalist community. Thus, considered in the light of demographic statistics, Jewish immigration to Palestine from 1881 to 1914 was largely a continuation of its pre-Zionist past. The specific historic importance of Zionism in the population transfer is nevertheless said to have been that a number of Jewish plantation villages and the beginnings of a farmer-worker class were established. This conclusion, too, has been contested. The polemical bias of the criticism is sometimes transparent, but it has underscored significant qualifications nevertheless. Characteristically Zionist innovations such as the revival of spoken Hebrew were "foreshadowed" by "precursors" in earlier generations. Opposition to the revival of spoken Hebrew became a hallmark of the Ashkenazi traditionalist establishment only after Zionism arose. In earlier decades, many had defended the holy tongue in Europe as one of the main points in their resistance to religious modernism; in Palestine, there were traditionalists who practiced Hebrew speaking as a religious exercise, and even dreamed of its revival as the national vernacular. Moreover, the rigid ideological separation of the two camps after Zionism arose was neither immediate nor complete; some settlers belonged to both the old and the new social structures.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Palestine/Israel

- ^ The First Aliyah (1882–1903) Jewish Virtual Library

- ^ "Industrial Revolution". www.let.leidenuniv.nl. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ Jaskow, Rahel (6 May 2015). "Jewish activists move into building in Arab Jerusalem neighborhood Structure in Silwan was once the synagogue of a village built there for Yemenite immigrants in the 1880s, NGO claims". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ^ Ben-Gedalyahu, Tzvi (7 May 2015). "Jews Move into Former Yemenite Synagogue in Silwan Valley The building is one of many where the British Mandate evicted Jews and let Arabs take over". The Jewish Press. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ^ The Jews of the Middle East and North Africa in Modern Times, by Reeva Spector Simon, Michael Menachem Laskier, Sara Reguer editors, Columbia University Press, 2003, page 406

- ^ Malley, JP O’. "With spy Sarah Aaronsohn's suicide, Israeli history was rewritten, claims author". www.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved 2020-12-12.

- ^ History of the Jews in Russia and the Soviet Union#Mass emigration and political activism

- ^ Kark (2001), p. 317

- ^ Morris, Benny. Righteous Victims: A history of the Zionist-Arab Conflict, 1881–2001. Vintage Books, 2001, p. 49.

Bibliography[]

- Kark, Ruth; Oren-Nordheim, Michal (2001). Jerusalem and Its Environs. Magnes Press. ISBN 0-8143-2909-8.

Further reading[]

- Ben-Gurion, David (1976), From Class to Nation: Reflections on the Vocation and Mission of the Labor Movement, Am Oved (in Hebrew)

External links[]

Media related to First Aliyah at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to First Aliyah at Wikimedia Commons

- Aliyah

- Jews and Judaism in Europe

- Jews and Judaism in Yemen

- Jews and Judaism in Ottoman Palestine

- 1882 in Ottoman Syria

- Political movements of the Ottoman Empire

- Jews and Judaism in Ottoman Galilee