First Italo-Ethiopian War

| First Italo-Ethiopian War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Scramble for Africa | |||||||||

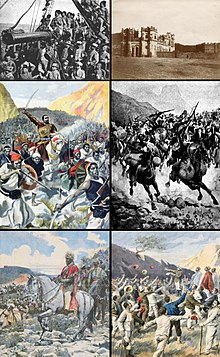

Clockwise from top left: Italian soldiers en route to Massawa; castle of Yohannes IV at Mek'ele;[7] Ethiopian cavalry at the Battle of Adwa; Italian prisoners are freed following the end of hostilities; Menelik II at Adwa; Ras Makonnen leading Ethiopian troops in the Battle of Amba Alagi | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Support: Eritrean rebels[6] | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

Bahta Hagos † | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 18,000[8]–25,000[9] |

196,000[9]

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

18,000 casualties: 7,500 Italians dead[11] 7,100 Eritreans dead[11] 1,428 Italians wounded[11] 1,865 Italians captured[11] |

17,000 casualties: 7,000 dead[11] 10,000 wounded[11] | ||||||||

The First Italo-Ethiopian War[a] was fought between Italy and Ethiopia from 1895 to 1896. It originated from the disputed Treaty of Wuchale, which the Italians claimed turned Ethiopia into an Italian protectorate. Full-scale war broke out in 1895, with Italian troops from Italian Eritrea having initial success until Ethiopian troops counterattacked Italian positions and besieged the Italian fort of Mekele, forcing its surrender.

Italian defeat came about after the Battle of Adwa, where the Ethiopian army dealt the heavily outnumbered Italian soldiers and Eritrean askaris a decisive blow and forced their retreat back into Eritrea. Some Eritreans, regarded as traitors by the Ethiopians, were also captured and mutilated.[12] The war concluded with the Treaty of Addis Ababa. Because this was one of the first decisive victories by African forces over a European colonial power,[13] this war became a preeminent symbol of pan-Africanism and secured Ethiopia's sovereignty until 1937.[14]

Background[]

The Khedive of Egypt Isma'il Pasha, better known as "Isma'il the Magnificent" had conquered Eritrea as part of his efforts to give Egypt an African empire.[15][16] Isma'il had tried to follow up that conquest with Ethiopia, but the Egyptian attempts to conquer that realm ended in humiliating defeat. After Egypt's bankruptcy in 1876[17] followed by the Ansar revolt under the leadership of the Mahdi in 1881, the Egyptian position in Eritrea was hopeless with the Egyptian forces cut off and unpaid for years. By 1884 the Egyptians began to pull out of both Sudan and Eritrea.[16]

Egypt had been very much in the French sphere of influence until 1882 when the British occupied Egypt. A major goal of French foreign policy until 1904 was to diminish British influence in Egypt and restore it to its place in the French sphere of influence, and in 1883 the French created the colony of French Somaliland which allowed for the establishment of a French naval base at Djibouti on the Red Sea.[16] The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 had turned the Horn of Africa into a very strategic region as a navy based in the Horn could interdict any shipping going up and down the Red Sea. By building naval bases on the Red Sea that could intercept British shipping in the Red Sea, the French hoped to reduce the value of the Suez Canal for the British, and thus "lever" them out of Egypt. A French historian in 1900 wrote: "The importance of Djibouti lies almost solely in the uniqueness of its geographic position, which makes it a port of transit and natural entrepôt for areas more infinitely more populated than its own territory...the rich provinces of central Ethiopia."[18] The British historian Harold Marcus noted that for the French, "Ethiopia represented the entrance to the Nile valley; if she could obtain hegemony over Ethiopia, her dream of a west to east French African empire would be closer to reality".[18] In response, Britain consistently supported Italian ambitions in the Horn of Africa as the best way of keeping the French out.[18]

On 3 June 1884, the Hewett Treaty was signed between Britain, Egypt and Ethiopia that allowed the Ethiopians to occupy parts of Eritrea and allowed Ethiopian goods to pass in and out of Massawa duty-free.[16] From the viewpoint of Britain, it was highly undesirable that the French replace the Egyptians in Eritrea as that would allow the French to have more naval bases on the Red Sea that could interfere with British shipping using the Suez Canal, and as the British did not want the financial burden of ruling Eritrea, they looked for another power who would be interested in replacing the Egyptians.[16] The Hewett treaty seemed to suggest that Eritrea would fall into the Ethiopian sphere of influence as the Egyptians pulled out.[16] After initially encouraging the Emperor Yohannes IV to move into Eritrea to replace the Egyptians, London decided to have the Italians move into Eritrea.[16] In his history of Ethiopia, British historian Augustus Wylde wrote: "England made use of King John [Emperor Yohannes] as long as he was of any service and then threw him over to the tender mercies of Italy...It is one of our worst bits of business out of the many we have been guilty of in Africa...one of the vilest bites of treachery".[16] After the French had unexpectedly made Tunis into their protectorate in 1881, outraging opinion in Italy over the so-called "Schiaffo di Tunisi" (the "slap of Tunis"), Italian foreign policy had been extremely anti-French, and from the British viewpoint the best way of ensuring the Eritrean ports on the Red Sea stayed out of French hands was by allowing the staunchly anti-French Italians move in. In 1882, Italy had joined the Triple Alliance, allying herself with Austria and Germany against France.

On 5 February 1885 Italian troops landed at Massawa to replace the Egyptians.[16] The Italian government for its part was more than happy to embark upon an imperialist policy to distract its people from the failings in post Risorgimento Italy.[16] In 1861, the unification of Italy was supposed to mark the beginning of a glorious new era in Italian life, and many Italians were gravely disappointed to find that not much had changed in the new Kingdom of Italy with the vast majority of Italians still living in abject poverty. To compensate, a chauvinist mood was rampant among the upper classes in Italy with the newspaper Il Diritto writing in an editorial: "Italy must be ready. The year 1885 will decide her fate as a great power. It is necessary to feel the responsibility of the new era; to become again strong men afraid of nothing, with the sacred love of the fatherland, of all Italy, in our hearts".[16] On the Ethiopian side, the wars that Emperor Yohannes had waged first against the invading Egyptians in the 1870s and then more so against the Sudanese Mahdiyya state in the 1880s had been presented by him to his subjects as holy wars in defense of Orthodox Christianity against Islam, reinforcing the Ethiopian belief that their country was an especially virtuous and holy land.[19] The struggle against the Ansar from Sudan complicated Yohannes's relations with the Italians, whom he sometimes asked to provide him with guns to fight the Ansar and other times he resisted the Italians and proposed a truce with the Ansar.[19]

On 18 January 1887, at a village named Saati, an advancing Italian Army detachment defeated the Ethiopians in a skirmish, but it ended with the numerically superior Ethiopians surrounding the Italians in Saati after they retreated in face of the enemy's numbers.[20] Some 500 Italian soldiers under Colonel de Christoforis together with 50 Eritrean auxiliaries were sent to support the besieged garrison at Saati.[20] At Dogali on his way to Saati, de Christoforis was ambushed by an Ethiopian force under Ras Alula, whose men armed with spears skillfully encircled the Italians who retreated to one hill and then to another higher hill.[20] After the Italians ran out of ammunition, Ras Alula ordered his men to charge and the Ethiopians swiftly overwhelmed the Italians in an action that featured bayonets against spears.[20] The Battle of Dogali ended with the Italians losing 23 officers and 407 other ranks killed.[20] As a result of the defeat at Dogali, the Italians abandoned Saati and retreated back to the Red Sea coast.[21] Italians newspapers called the battle a "massacre" and excoriated the Regio Esercito for not assigning de Chistoforis enough ammunition.[21] Having, at first, encouraged Emperor Yohannes to move into Eritrea, and then having encouraged the Italians to also do so, London realised a war was brewing and decided to try to mediate, largely out of the fear that the Italians might actually lose.[16]

The British consul in Zanzibar, Gerald Portal, was sent in 1887 to mediate between the Ethiopians and Italians before war broke out.[16]Upon meeting the Emperor Yohannes on 4 December 1887, he presented him with gifts and a letter from Queen Victoria urging him to settle with the Italians.[22] Portal reported: "What might have been possible in August or September was impossible in December, when the whole of the immense available forces in the country were already under arms; and that there now remains no hope of a satisfactory adjustment of the difficulties between Italy and Abyssinia [Ethiopia] until the question of the relative supremacy of these two nations has been decided by an appeal to the fortunes of war... No one who has once seen the nature of the gorges, ravines and mountain passes near the Abyssinian frontier can doubt for a moment that any advance by a civilised army in the face of the hostile Abyssinian hordes would be accomplished at the price of a fearful loss of life on both sides. ... The Abyssinians are savage and untrustworthy, but they are also redeemed by the possession of an unbounded courage, by a disregard of death, and by a national pride which leads them to look down on every human being who has not had the good fortune to be born an Abyssinian".[22] Portal ended by writing that the Italians were making a mistake in preparing to go war against Ethiopia: "It is the old, old story, contempt of a gallant enemy because his skin happens to be chocolate or brown or black, and because his men have not gone through orthodox courses of field-firing, battalion drill, or 'autumn maneuvers'".[22]

The defeat at Dogali made the Italians cautious for a moment, but on 10 March 1889, Emperor Yohannes died after being wounded in battle against the Ansar and on his deathbed admitted that Ras Mengesha, the supposed son of his brother, was actually his own son and asked that he succeed him.[21] The revelation that the emperor had slept with his brother's wife scandalised intensely Orthodox Ethiopia, and instead the Negus Menelik was proclaimed emperor on 26 March 1889.[21] Ras Mengesha, one of the most powerful Ethiopian noblemen, was unhappy about being by-passed in the succession and for a time allied himself with the Italians against the Emperor Menelik.[21] Under the feudal Ethiopian system, there was no standing army, and instead, the nobility raised up armies on behalf of the Emperor. In December 1889, the Italians advanced inland again and took the cities of Asmara and Keren and in January 1890 took Adowa.[21]

Treaty of Wuchale[]

On 25 March 1889, the Shewa ruler Menelik II, having conquered Tigray and Amhara, declared himself Emperor of Ethiopia (or "Abyssinia", as it was commonly called in Europe at the time). Barely a month later, on 2 May he signed the Treaty of Wuchale with the Italians, which apparently gave them control over Eritrea, the Red Sea coast to the northeast of Ethiopia, in return for recognition of Menelik's rule. Menelik II continued the policy of Tewodros II of integrating Ethiopia.

However, the bilingual treaty did not say the same thing in Italian and Amharic; the Italian version did not give the Ethiopians the "significant autonomy" written into the Amharic translation.[23] The Italian text stated that Ethiopia must conduct its foreign affairs through Italy (making it an Italian protectorate), but the Amharic version merely stated that Ethiopia could contact foreign powers and conduct foreign affairs using the embassy of Italy. Italian diplomats, however, claimed that the original Amharic text included the clause and Menelik knowingly signed a modified copy of the Treaty.[24] In October 1889, the Italians informed all of the other European governments because of the Treaty of Wuchale that Ethiopia was now an Italian protectorate and therefore the other European nations could not conduct diplomatic relations with Ethiopia.[25] With the exceptions of the Ottoman Empire, which still maintained its claim to Eritrea, and Russia, which disliked the idea of an Orthodox nation being subjugated to a Roman Catholic nation, all of the European powers accepted the Italian claim to a protectorate.[25]

The Italian claim that Menelik was aware of Article XVII turning his nation into an Italian protectorate seems unlikely given that the Emperor Menelik sent letters to Queen Victoria and Emperor Wilhelm II in late 1889 and was informed in the replies in early 1890 that neither Britain nor Germany could have diplomatic relations with Ethiopia on the account of Article XVII of the Treaty of Wuchale, a revelation that came as a great shock to the Emperor.[25] Victoria's letter was polite whereas Wilhelm's letter was somewhat more rude, saying that King Umberto I was a great friend of Germany and Menelik's violation of the supposed Italian protectorate was a grave insult to Umberto, adding that he never wanted to hear from Menelik again.[25] Moreover, Menelik did not know Italian and only signed the Amharic text of the treaty, being assured that there were no differences between the Italian and Amharic texts before he signed.[25] The differences between the Italian and Amharic texts were due to the Italian minister in Addis Ababa, Count Pietro Antonelli, who had been instructed by his government to gain as much territory as possible in negotiating with the Emperor Menelik. However, knowing Menelik was now enthroned as the King of Kings and had a strong position, Antonelli was in the unenviable situation of negotiating a treaty that his own government might disallow. Therefore, he inserted the statement making Ethiopia give up its right to conduct its foreign affairs to Italy as a way of pleasing his superiors who might otherwise have fired him for only making small territorial gains.[25] Antonelli was fluent in Amharic and given that Menelik only signed the Amharic text he could not have been unaware that the Amharic version of Article XVII only stated that the King of Italy places the services of his diplomats at the disposal of the Emperor of Ethiopia to represent him abroad if he so wished.[25] When his subterfuge was exposed in 1890 with Menelik indignantly saying he would never sign away his country's independence to anybody, Antonelli who left Addis Ababa in mid 1890 resorted to racism, telling his superiors in Rome that as Menelik was a black man, he was thus intrinsically dishonest and it was only natural the Emperor would lie about the protectorate he supposedly willingly turned his nation into.[25]

Francesco Crispi, the Italian Prime Minister was an ultra-imperialist who believed the newly unified Italian state required "the grandeur of a second Roman empire".[21] Crispi believed that the Horn of Africa was the best place for the Italians to start building the new Roman empire.[21] The American journalist James Perry wrote that "Crispi was a fool, a bigot and a very dangerous man".[21] Because of the Ethiopian refusal to abide by the Italian version of the treaty and despite economic handicaps at home, the Italian government decided on a military solution to force Ethiopia to abide by the Italian version of the treaty. In doing so, they believed that they could exploit divisions within Ethiopia and rely on tactical and technological superiority to offset any inferiority in numbers. The efforts of Emperor Menelik, viewed as pro-French by London, to unify Ethiopia and thus bring the source of the Blue Nile under his control was perceived in Whitehall as a threat to their influence in Egypt.[18] As Menelik became increasingly successful in unifying Ethiopia, the British government courted the Italians to counter Ethiopian expansion.[18]

There was a broader, European background as well: the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy was under some stress, with Italy being courted by the British government. Two secret Anglo-Italian protocols were signed in 1891, leaving most of Ethiopia in Italy's sphere of influence.[26] France, one of the members of the opposing Franco-Russian Alliance, had its own claims on Eritrea and was bargaining with Italy over giving up those claims in exchange for a more secure position in Tunisia. Meanwhile, Russia was supplying weapons and other aid to Ethiopia.[23] It had been trying to gain a foothold in Ethiopia,[27] and in 1894, after denouncing the Treaty of Wuchale in July, it received an Ethiopian mission in St. Petersburg and sent arms and ammunition to Ethiopia.[28] This support continued after the war ended.[29] The Russian travel writer Alexander Bulatovich who went to Ethiopia to serve as a Red Cross volunteer with the Emperor Menelik made a point of emphasizing in his books that the Ethiopians converted to Christianity before any of the Europeans ever did, described the Ethiopians as a deeply religious people like the Russians, and argued the Ethiopians did not have the "low cultural level" of the other African peoples, making them equal to the Europeans.[30] Germany and Austria supported their ally in the Triple Alliance Italy while France and Russia supported Ethiopia.

Opening campaigns[]

In 1893, judging that his power over Ethiopia was secure, Menelik repudiated the treaty; in response the Italians ramped up the pressure on his domain in a variety of ways, including the annexation of small territories bordering their original claim under the Treaty of Wuchale, and finally culminating with a military campaign and across the Mareb River into Tigray (on the border with Eritrea) in December 1894. The Italians expected disaffected potentates like Negus Tekle Haymanot of Gojjam, Ras Mengesha Yohannes, and the Sultan of Aussa to join them; instead, all of the ethnic Tigrayan or Amharic peoples flocked to the Emperor Menelik's side in a display of both nationalism and anti-Italian feeling, while other peoples of dubious loyalty (e.g. the Sultan of Aussa) were watched by Imperial garrisons.[31] In June 1894, Ras Mengesha and his generals had appeared in Addis Ababa carrying large stones which they dropped before the Emperor Menelik (a gesture that is a symbol of submission in Ethiopian culture).[21] In Ethiopia, the popular saying at the time was: "Of a black snake's bite, you may be cured, but from the bite of a white snake, you will never recover."[21] There was an overwhelming national unity in Ethiopia as various feuding noblemen rallied behind the emperor who insisted that Ethiopia, unlike the other African nations, would retain its freedom and not be subjected to Italy.[21] The ethnic rivalries between the Tigrians and the Amhara that the Italians were counting upon did not prove to be a factor as Menelik pointed out that the Italians held all Ethnic Africans, regardless of their individual ethnic backgrounds, in contempt, noting the segregation policies in Eritrea applied to all Ethnic Africans.[21] Further, Menelik had spent much of the previous four years building up a supply of modern weapons and ammunition, acquired from the French, British, and the Italians themselves, as the European colonial powers sought to keep each other's North African aspirations in check. They also used the Ethiopians as a proxy army against the Sudanese Mahdists.

In December 1894, Bahta Hagos led a rebellion against the Italians in Akkele Guzay, claiming support of Mengesha. Units of General Oreste Baratieri's army under Major crushed the rebellion and killed Bahta at the Battle of Halai. The Italian army then occupied the Tigrian capital, Adwa. Baratieri suspected that Mengesha would invade Eritrea, and met him at the Battle of Coatit in January 1895. The victorious Italians chased the retreating Mengesha, capturing weapons and important documents proving his complicity with Menelik. The victory in this campaign, along with previous victories against the Sudanese Mahdists, led the Italians to underestimate the difficulties to overcome in a campaign against Menelik.[32] At this point, Emperor Menelik turned to France, offering a treaty of alliance; the French response was to abandon the Emperor in order to secure Italian approval of the Treaty of Bardo which would secure French control of Tunisia. Virtually alone, on 17 September 1895, Emperor Menelik issued a proclamation calling up the men of Shewa to join his army at Were Ilu.[33]

As the Italians were poised to enter Ethiopian territory, the Ethiopians mobilised en masse all over the country.[34] Helping it was the newly updated imperial fiscal and taxation system. As a result, a hastily mobilised army of 196,000 men gathered from all parts of Abyssinia, more than half of whom were armed with modern rifles, rallied at Addis Ababa in support of the Emperor and defence of their country.[9]

The only European ally of Ethiopia was Russia.[3][28][29] The Ethiopian emperor sent his first diplomatic mission to St. Petersburg in 1895. In June 1895, the newspapers in St. Petersburg wrote, "Along with the expedition, Menelik II sent his diplomatic mission to Russia, including his princes and his bishop". Many citizens of the capital came to meet the train that brought Prince Damto, General Genemier, Prince Belyakio, Bishop of Harer Gabraux Xavier and other members of the delegation to St. Petersburg. On the eve of war, an agreement providing military help for Ethiopia was concluded.[35][36]

The next clash came at Amba Alagi on 7 December 1895, when Ethiopian soldiers overran the Italian positions dug in on the natural fortress, and forced the Italians to retreat back to Eritrea.[citation needed] The remaining Italian troops under General Giuseppe Arimondi reached the unfinished Italian fort at Mekele. Arimondi left there a small garrison of approximately 1,150 Askaris and 200 Italians, commanded by Major Giuseppe Galliano, and took the bulk of his troops to Adigrat, where Oreste Baratieri, the Italian Commander, was concentrating the Italian Army.

The first Ethiopian troops reached Mekele in the following days. Ras Makonnen surrounded the fort at Mekele on 18 December, but the Italian Commander adroitly used promises of a negotiated surrender to prevent the Ras from attacking the fort. By the first days of January, Emperor Menelik, accompanied by his Queen Taytu Betul, had led large forces into Tigray, and besieged the Italians for sixteen days (6–21 January 1896), making several unsuccessful attempts to carry the fort by storm, until the Italians surrendered with permission from the Italian Headquarters.[citation needed] Menelik allowed them to leave Mekele with their weapons, and even provided the defeated Italians mules and pack animals to rejoin Baratieri.[37] While some historians read this generous act as a sign that Emperor Menelik still hoped for a peaceful resolution to the war, Harold Marcus points out that this escort allowed him a tactical advantage: "Menelik craftily managed to establish himself in Hawzien, at , near Adwa, where the mountain passes were not guarded by Italian fortifications."[38]

Heavily outnumbered, Baratieri refused to engage, knowing that due to their lack of infrastructure the Ethiopians could not keep large numbers of troops in the field much longer. However, Baratieri also never knew the true numerical strength of the Ethiopian army he faced, so he further fortified his positions in the Tigray instead of advancing. But the Italian government of Francesco Crispi was unable to accept being stymied by non-Europeans. The prime minister specifically ordered Baratieri to advance deep into enemy territory and bring about a battle.

Battle of Adwa[]

The decisive battle of the war was the Battle of Adwa on March 1, 1896, which took place in the mountainous country north of the actual town of Adwa (or Adowa). The Italian army comprised four brigades totaling approximately 17,700 men, with fifty-six artillery pieces; the Ethiopian army comprised several brigades numbering between 73,000 and 120,000 men (80–100,000 with firearms: according to Richard Pankhurst, the Ethiopians were armed with approximately 100,000 rifles of which about half were quick-firing),[10] with almost fifty artillery pieces.

General Baratieri planned to surprise the larger Ethiopian force with an early morning attack, expecting his enemy to be asleep. However, the Ethiopians had risen early for Church services and, upon learning of the Italian advance, promptly attacked. The Italian forces were hit by wave after wave of attacks, until Menelik released his reserve of 25,000 men, destroying an Italian brigade. Another brigade was cut off, and destroyed by a cavalry charge. The last two brigades were destroyed piecemeal. By noon, the Italian survivors were in full retreat.

While Menelik's victory was in a large part due to the sheer force of numbers, his troops were well-armed because of his careful preparations. The Ethiopian army only had a feudal system of organisation but proved capable of properly executing the strategic plan drawn up in Menelik's headquarters. However, the Ethiopian army also had its problems. The first was the quality of its arms, as the Italian colonial authorities in Eritrea prevented the transportation of 30,000–60,000 modern Mosin–Nagant rifles and Berdan rifles from Russia into landlocked Ethiopia.[citation needed] The rest of the Ethiopian army was equipped with swords and spears. Secondly, the Ethiopian army's feudal organisation meant that nearly the entire force was composed of peasant militia. Russian military experts advising Menelik II suggested a full-contact battle with Italians, to neutralise the Italian fire superiority, instead of engaging in a campaign of harassment designed to nullify problems with arms, training, and organisation.[36][39]

Some Russian councillors of Menelik II and a team of fifty Russian volunteers participated in the battle, among them Nikolay Leontiev, an officer of the Kuban Cossack army.[1] Russian support for Ethiopia also led to a Russian Red Cross mission, which arrived in Addis Ababa some three months after Menelik's Adwa victory.[2]

The Italians suffered about 7,000 killed and 1,500 wounded in the battle and subsequent retreat back into Eritrea, with 3,000 taken prisoner; Ethiopian losses have been estimated around 4,000 killed and 8,000 wounded.[40][41] In addition, 2,000 Eritrean Askaris were killed or captured. Italian prisoners were treated as well as possible under difficult circumstances, but 800 captured Askaris, regarded as traitors by the Ethiopians, had their right hands and left feet amputated.[42][43] Menelik, knowing that the war was very unpopular in Italy with the Italian Socialists in particular condemning the policy of the Crispi government, chose to be a magnanimous victor, making it clear that he saw a difference between the Italian people and Crispi.[18]

Outcome and consequences[]

Menelik retired in good order to his capital, Addis Ababa, and waited for the fallout of the victory to hit Italy. Riots broke out in several Italian cities, and within two weeks, the Crispi government collapsed amidst Italian disenchantment with "foreign adventures".[44]

Menelik secured the Treaty of Addis Ababa in October, which delineated the borders of Eritrea and forced Italy to recognise the independence of Ethiopia. Delegations from the United Kingdom and France—whose colonial possessions lay next to Ethiopia—soon arrived in the Ethiopian capital to negotiate their own treaties with this newly proven power. Owing to Russia's diplomatic support of her fellow Orthodox nation, Russia's prestige greatly increased in Ethiopia. The adventuresome Seljan brothers, Mirko and Stjepan, who were actually Catholic Croats, were warmly welcomed when they arrived in Ethiopia in 1899 when they misinformed their hosts by saying they were Russians.[45] As France supported Ethiopia with weapons, French influence increased markedly.[18] Prince Henri of Orléans, the French traveller, wrote: "France gave rifles to this country and taking the hand of its Emperor like an elder sister has explained to him the old motto which has guided her across the centuries of greatness and glory: Honor and Country!".[18] In December 1896, a French diplomatic mission in Addis Ababa arrived and on 20 March 1897 signed a treaty that was described as "véritable traité d'alliance.[18] In turn, the increase in French influence in Ethiopia led to fears in London that the French would gain control of the Blue Nile and would be able to "lever" the British out of Egypt.[18] To keep control of the Nile in Egypt, the British government decided in March 1896 to advance down the Nile from Egypt into the Sudan to conquer the Mahdiyya state.[18] On 12 March 1896, upon hearing of the Italian defeat at the Battle of Adwa, the British Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, gave instructions for the British forces in Egypt to occupy the Sudan before the French could conquer the Mahdiyya state, stating that no hostile power could be allowed to control the Nile.[18]

In 1935, Italy launched a second invasion, which resulted in an Italian victory and the annexation of Ethiopia to Italian East Africa until the Italians were defeated in the Second World War and expelled by the British Empire, with some assistance from Ethiopian arbegnoch guerilla.[46] The Italians successively started a guerrilla war until 1943 in some areas of northern Ethiopia, supporting the rebellion of the Galla in 1942.

Gallery[]

Russian military officer Nikolay Leontiev with a member of the Ethiopian military

An Ethiopian painting commemorating the Battle of Adwa

Two Italian soldiers captured and held captive after the Battle of Adwa.

See also[]

- Italo-Ethiopian War of 1887–1889

- Second Italo-Ethiopian War

- Italian Empire

- Military history of Ethiopia

Notes[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The activities of the officer the Kuban Cossack army N. S. Leontjev in the Italian-Ethiopic war in 1895–1896".

- ^ Jump up to: a b Richard, Pankhurst. "Ethiopia's Historic Quest for Medicine, 6". The Pankhurst History Library. Archived from the original on 2011-10-03.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Patman 2009, pp. 27–30

- ^ "Soviet Appeasement, Collective Security, and the Italo-Ethiopian war of 1935 and 1936". libcom.org.

- ^ Thomas Wilson, Edward (1974). Russia and Black Africa Before World War II. New York. pp. 57–58.

- ^ Haggai, Erlich (1997). Ras Alula and the scramble for Africa – a political biography: Ethiopia and Eritrea 1875–1897. African World Press.

- ^ "Ethiopian Treasures". ethiopiantreasures.co.uk. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ^ Vandervort 1998, p. 160

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "First Italo-Abyssinian War: Battle of Adowa". HistoryNet. June 12, 2006.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pankhurst 2001, p. 190

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Milkias, Paulos (2005). "The Battle of Adwa: The Historic Victory of Ethiopia over European Colonialism". In Paulos Milkias; Getachew Metaferia (eds.). The Battle of Adwa: Reflections on Ethiopia's Historic Victory Against European Colonialism. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-87586-414-3.

- ^ "Photo of some of the Eritrean Ascari mutilated".

- ^ "5 Fascinating Battles of the African Colonial Era". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- ^ Professor Kinfe Abraham, "The Impact of the Adowa Victory on The Pan-African and Pan-Black Anti-Colonial Struggle," Address delivered to The Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Addis Ababa University, 8 February 2006

- ^ Marsot, Afaf (1975). "The Porte and Ismail Pasha's Quest for Autonomy". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 12 (1975): 89–96. doi:10.2307/40000011. JSTOR 40000011. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m Perry 2005, p. 196

- ^ Atkins, Richard (1974). "The Origins of the Anglo-French Condominium in Egypt, 1875-1876". The Historian. 36 (2): 264–282. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1974.tb00005.x. JSTOR 24443685. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l Marcus, Harold G. (1963). "A Background to Direct British Diplomatic Involvement in Ethiopia, 1894–1896". Journal of Ethiopian Studies. 1 (2): 121–132. JSTOR 41965700.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Erlich, Haggai (2007). "Ethiopia and the Mahdiyya – You Call Me a Chicken?". Journal of Ethiopian Studies. 40 (1/2): 219–249. JSTOR 41988228.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Perry 2005, p. 200

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m Perry 2005, p. 201

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Perry 2005, p. 199

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gardner 2015, p. 107

- ^ Pastoretto, Piero. "Battaglia di Adua" (in Italian). Archived from the original on May 31, 2006. Retrieved 2006-06-04.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Rubenson, Sven (1964). "The Protectorate Paragraph of the Wichale Treaty". The Journal of African History. 5 (2): 243–283. doi:10.1017/S0021853700004837. JSTOR 179872.

- ^ Streit, Clarence K. (22 July 1935). "Britain Gave Italy Rights Under Secret Pact in 1891 To Rule Most of Ethiopia" (PDF). The New York Times.

- ^ Burke, Edmund (1892). "East Africa". The Annual Register of World Events: A Review of the Year. Annual Register, New Series. 133. Longmans, Green. pp. 397–399.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Vestal, Theodore M. (2005). "Reflections on the Battle of Adwa and its Significance for Today". In Paulos Milkias; Getachew Metaferia (eds.). The Battle of Adwa: Reflections on Ethiopia's Historic Victory Against European Colonialism. Algora. pp. 21–35. ISBN 978-0-87586-414-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Eribo 2001, p. 55

- ^ Mirzeler, Mustafa Kemal (2005). "Reading "Ethiopia through Russian Eyes": Political and Racial Sentiments in the Travel Writings of Alexander Bulatovich, 1896–1898". History in Africa. 32: 281–294. doi:10.1353/hia.2005.0017. JSTOR 20065745. S2CID 52044875.

- ^ Prouty 1986, p. 143

- ^ Berkeley 1969

- ^ Marcus 1995, p. 160

- ^ "The Crown Council of Ethiopia".

- ^ "Russian mission to Abyssinia". 28 February 1895.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Who Was Count Abai?". St.Petersburg: through centuries. Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2010-10-05.

- ^ Prouty 1986, pp. 144–151

- ^ Marcus 1995, p. 167

- ^ "Cossacks of the emperor Menelik II". tvoros.ru. Archived from the original on 2015-07-16. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ^ von Uhlig, Encyclopaedia, p. 109.

- ^ Pankhurst 2001, pp. 191–192

- ^ Augustus B. Wylde, Modern Abyssinia (London: Methuen, 1901), p. 213

- ^ "Photo of some of the Eritrean Askaris mutilated".

- ^ Vandervort 1998, p. 164

- ^ Molvaer, Reidulf K. (2010). "The Seljan Brothers and the Expansionist Policies of Emperor Minïlik II of Ethiopia". International Journal of Ethiopian Studies. 5 (2): 79–90. JSTOR 41757592.

- ^ Stanton, Ramsamy & Seybolt 2012, p. 308

- Bibliography

- Berkeley, George (1969). Reprint (ed.). The campaign of Adowa and the rise of Menelik. Negro University Press. ISBN 978-1-56902-009-8.

- Clodfelter, Micheal (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015 (4th ed.). McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-7470-7.

- Eribo, Festus (2001). In Search of Greatness: Russia's Communications with Africa and the World. Ablex Publishing. ISBN 978-1-56750-532-0.

- Gardner, Hall (2015). The Failure to Prevent World War I: The Unexpected Armageddon. Ashgate. ISBN 978-1-4724-3058-8.

- Jonas, Raymond (2011). The Battle of Adwa: African Victory in the Age of Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-06279-5.

- Marcus, Harold G. (1995). The Life and Times of Menelik II: Ethiopia 1844–1913. Red Sea Press. ISBN 978-1-56902-010-4.

- Pankhurst, Richard (2001). The Ethiopians: A History. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-22493-8.

- Patman, Robert G. (2009). The Soviet Union in the Horn of Africa: The Diplomacy of Intervention and Disengagement. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-10251-3.

- Perry, James M. (2005). Arrogant Armies: Great Military Disasters and the Generals Behind Them. Castle Books. ISBN 978-0-7858-2023-9.

- Prouty, Chris (1986). Empress Taytu and Menilek II: Ethiopia 1883–1910. Red Sea Press.

- Stanton, Andrea L.; Ramsamy, Edward; Seybolt, Peter J. (2012). Cultural Sociology of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa: An Encyclopedia. SAGE Publications. p. 308. ISBN 978-1-4129-8176-7.

- Vandervort, Bruce (1998). Wars of Imperial Conquest in Africa, 1830–1914. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-33383-4.

![]() Media related to First Italo-Ethiopian War at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to First Italo-Ethiopian War at Wikimedia Commons

- First Italo-Ethiopian War

- Italian East Africa

- 1895 in Ethiopia

- 1896 in Ethiopia

- 1895 in Italy

- 1896 in Italy

- Conflicts in 1895

- Conflicts in 1896

- History of Ethiopia

- Wars involving Ethiopia

- Wars involving Italy

- Ethiopia–Italy military relations

- African resistance to colonialism