Formline art

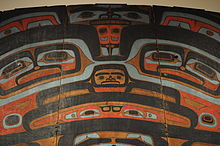

Formline art is a feature in the indigenous art of the Northwest Coast of North America, distinguished by the use of characteristic shapes referred to as ovoids, U forms and S forms. Coined by Bill Holm in his 1965 book Northwest Coast Indian Art: An Analysis of Form,[1][2] the "formline is the primary design element on which Northwest Coast art depends, and by the turn of the 20th century, its use spread to the southern regions as well. It is the positive delineating force of the painting, relief and engraving. Formlines are continuous, flowing, curvilinear lines that turn, swell and diminish in a prescribed manner. They are used for figure outlines, internal design elements and in abstract compositions."[3]

History[]

After European contact in the late 18th century, the peoples who produced Northwest Coast art suffered huge population losses due to diseases such as smallpox, and cultural losses due to forced assimilation into European-North American culture, Canadian colonial cultural suppression, and the confiscation or destruction of traditional art and artifacts of ritual and governance. The production of their art dropped drastically.

Toward the end of the 19th century, Northwest Coast artists began producing work for commercial sale, such as small argillite carvings produced by the Haida. The end of the 19th century also saw large-scale export of totem poles, masks and other traditional art objects from the region to museums and private collectors around the world. Some of this export was accompanied by financial compensation to people who had a right to sell the art, and some was not.

In the early 20th century, very few First Nations artists in the Northwest Coast region were producing art. A tenuous link to older traditions remained in artists such as Charles Gladstone (Haida), Stanley George (Heiltsuk) and Mungo Martin (Kwakwaka'wakw). The mid-20th century saw a revival of interest and production of Northwest Coast art, due to the influence of artists and critics such as Bill Reid, a grandson of Charles Gladstone, and others. This renewal of art is part of a wider cultural and political awakening among First Nations. It also saw an increasing demand for the return of art objects (known as Repatriation) that were illegally or immorally taken from First Nations communities. This demand continues to the present day. Today, there are numerous art schools teaching formal Northwest Coast art of various styles, and there is a growing market for new art in this style.[4]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ ""Haida Art - Mapping an Ancient Language", musee-mccord.qc.ca. Retrieved Nov. 22, 2011". Archived from the original on 2014-05-13. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ ""Bill Holm: Northwest Coast Indian Art", washington.edu. Retrieved Nov. 22, 2011". Archived from the original on 2011-04-25. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ Marjorie M. Halpin (March 4, 2015). "Northwest Coast Indigenous Art". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- ^ Jonathan Meuli. Shadow House: Interpretations of Northwest Coast Art. ISBN 90-5823-083-X

Further reading[]

- Hawthorn, Audrey. Art of the Kwakiutl Indians. Vancouver: University of British Columbia, 1967.

- Holm, Bill. Northwest Coast Indian Art: An Analysis of Form. University of Washington Press: Seattle, 1965. ISBN 978-0-295-95102-7

- McLennan, Bill and Karen Duffek. "The Transforming Image: Painted Arts of Northwest Coast First Nations." University of British Columbia. 2000. ISBN 0-7748-0427-0

External links[]

- Canadian art movements

- Indigenous art in Canada

- American art movements

- Northwest Coast art