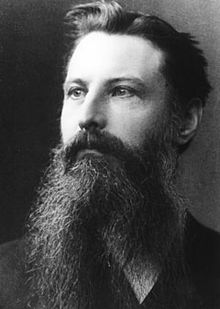

Friedrich Wilhelm Zopf

Friedrich Wilhelm Zopf | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | December 12, 1846 |

| Died | June 24, 1909 (aged 63) |

| Nationality | German |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Botany and Mycology |

Friedrich (or Friederich) Wilhelm Zopf (December 12, 1846 – June 24, 1909) was a well-known German botanist and mycologist. He dedicated to his whole life with fungal biology, particularly in classification of fungi and dye production in fungi and lichens.[1] Besides, his textbook on fungi called “Die pilze in morphologischer, physiologischer, biologischer und systematischer beziehung (Translation: The mushrooms in morphological, physiological, biological and systematic relationship)” in 1890 was also an outstanding work on the subject for many decades.[2] The unicellular achlorophic microalgae Prototheca zopfii is named after him because of his profound suggestions and contributions to Krüger's pioneering work in Prototheca.[3] Thus, his numerous contributions gave him a special status in mycological history.

Early life[]

Wilhelm Zopf was born in Roßleben in Thuringia in 1846. Before going into biological science area, he has been an elementary school teacher in at Mansfeld when he was 21-year-old.[4]

Education and research career[]

In 1874, Wilhelm Zopf decided to leave his teaching position and turned into studying natural sciences at the University of Berlin. After that, he received his PhD with a dissertation entitled “Die von Conidienfrüchte von Fumago (Translation: Conidia of Fumago)” at the University of Halle in 1878.[4]

As Wilhelm Zopf obtained his degree, simultaneously, he backed to Berlin as an adjunct professor teaching at the Agricultural College for a few years. In 1883, he was invited to be a head of the cryptogamic laboratory at the University of Halle. In the period of 1883 to 1899, he made extensive studies on Chytridiales and other small aquatic fungi parasitic in algae and small animals. Likewise, he also published an authoritative fungal textbook in which he followed a classification similar in part to that of Julius Oscar Brefeld but placed Ascomycetes last in 1890. In this group, he made them went from the simple forms, like Saccharomyces, Endomyces, Gymnoascaceae, to Pezizales. In addition, he recognized the formation of in many ascomycetes and even the union of these in Pyronema, with club-shaped “”, but expressed doubt as to their real sexual function.[2]

In 1899, Wilhelm Zopf became a professor and a director of botanical garden in the University of Münster. He continued the research on fungal biology and systematics. During his work on fungal biology, he became more interested in secondary chemistry of these organisms, particularly the lichens. He published on more general problems related to lichen biology, particularly in the genus Cladonia. Finally, he died in Münster in 1909, and his name was commemorated by Edvard Vainio in naming of .[4]

Other scientific contributions[]

Wilhelm Zopf was the first people to carry out the chemical differences in lichens.[5] In 1907, his book “Die Flechtenstoffe in chemischer, botanischer, pharmakologischer und technischer Beziehung (Translation: The lichen substances in chemical, botanical, pharmacological and technical relationship)” was published. This book contained descriptions of over 150 chemical compounds found in lichens. In other words, we can say the science of lichen chemistry started with Wilhelm Zopf’s work.[6] Little was known about the actual structures of many of those compounds, but his work indeed gave a sounder basis for the use of chemistry in the taxonomy of lichens.[7]

Moreover, there were many fungi related to Wilhelm Zopf. For example, he circumscribed the genus of fungi Thielavia in 1876 and gave Monilia albicans its name in 1890. He also transferred which was described by English botanist James Edward Smith to the genus Rhizoplaca in 1905.

Although nematode-trapping fungus have been known since 1839, its predatory habit was first observed by Wilhelm Zopf as well.[8] This recorded observation of Arthrobotrys oligospora’s behavior was attributed to him in 1888. This kind of fungi actively captures small worms, generally classified as nematodes or roundworms.[9]

Selected publications[]

- Zopf, W. 1890: Die pilze in morphologischer, physiologischer, biologischer und systematischer Beziehung. Jena: E. Trewendt. 500 pp.

- Zopf, W. 1897: Zur Kenntniss der Flechtenstoffe (Vierte Mittheilung). Liebigs Annalen der Chemie 297: 271–312.

- Zopf, W. 1905: Biologische und morphologische Beobachtungen an Flechten. I. Berichte der Deutschen Botanischen Gesellschaft 23: 497–504.

- Zopf, W. 1906: Biologische und morphologische Beobachtungen an Flechten. II. 1. Über Ramalina kullensis n. sp. Berichte der Deutschen Botanischen Gesellschaft 24: 574 –580.

- Zopf, W. 1907: Die Flechtenstoffe in chemischer, botanischer, pharmakologischer und technischer Beziehung. Jena: G. Fischer. 450 pp.

- Zopf, W. 1908: Beiträge zu einer chemischen Monographie der Cladoniaceen. Berichte der Deutschen Botanischen Gesellschaft 26: 51–113.

References[]

- ^ "Wilhelm Zopf". Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg. 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pelletier, Bernard (2016). Empire Biota: Taxonomy and Evolution 2nd Edition. p. 241. ISBN 9781329874008.

- ^ Krüger, W (1894). "Kurze Charakteristik einiger niedrerer Organismen im Saftfluss der Laubbäume". Hedwigia. 33: 241–266.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kärnefelt, Ingvar; Scholz, Peter; Seaward, Mark; Thell, Arne (2012). "Lichenology in Germany: past, present and future". Schlechtendalia. 23: 1–90.

- ^ Zopf, Wilhelm (1895). "Zur Kenntniss der Flechtenstoffe". Annali di Chimica. 284 (1–2): 107–132. doi:10.1002/jlac.18952840110.

- ^ Stocker-Wörgötter, Elfie (2008). "Metabolic diversity of lichen-forming ascomycetous fungi: culturing, polyketide and shikimatemetabolite production, and PKS genes". Natural Product Reports. 25 (1): 188–200. doi:10.1039/b606983p. PMID 18250902.

- ^ "Chemistry after the 1860s". Australian National Botanic Gardens.

- ^ Zopf, Wilhelm (1888). "Zur Kenntnis der Infektionskrankheiten niederer Thiere und Pflanzen". Nova Academy of Caes. Leop. German. Nat. Cur. 52: 314–376.

- ^ "Some exceptions in biology: Worm-catching fungi". Baldscientist. 2014.

- ^ IPNI. Zopf.

External links[]

- Lichenology in Germany: past, present and future. [1]

- German lichenologists

- German mycologists

- 1846 births

- 1909 deaths

- Humboldt University of Berlin alumni

- Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg alumni

- People from Roßleben

- 19th-century German botanists