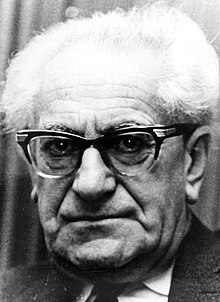

Fritz Bauer

Fritz Bauer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 16 July 1903 Stuttgart, Germany |

| Died | 1 July 1968 (aged 64) Frankfurt am Main |

| Political party | Social Democratic Party |

Fritz Bauer (16 July 1903 – 1 July 1968) was a German Jewish judge and prosecutor. He was instrumental in the post-war capture of former Holocaust planner Adolf Eichmann and also played an essential role in starting the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials.

Life and work[]

Bauer was born in Stuttgart, to Jewish parents, Ella (Hirsch) and Ludwig Bauer.[1] He attended Eberhard-Ludwigs-Gymnasium[2] and studied business and law at the Universities of Heidelberg, Munich and Tübingen.

In 1928, after receiving his PhD in law (at 25, Doktor der Rechte [Jur.Dr.] in Germany), Bauer became an assessor judge in the Stuttgart local district court. By 1920, he already had joined the Social Democratic Party (SPD). In the early 1930s, Bauer was, together with Kurt Schumacher, one of the leaders of the SPD's Reichsbanner defense league in Stuttgart. In May 1933, soon after the Nazi seizure of power, a plan to organize a general strike against the Nazis in the Stuttgart region failed, and Schumacher and Bauer were arrested with others and taken to Heuberg concentration camp. The more prominent and older Schumacher, who had been an outspoken opponent of the Nazis as an SPD deputy in the Reichstag, remained in concentration camps (which destroyed his health) until the end of World War II, whereas the young and largely unknown Bauer was released. A short time later Bauer, like most Jews, was dismissed from his civil service position.

In 1935, Bauer emigrated to Denmark. After the German occupation, the Danish authorities revoked his residence permit in April 1940 and interned him in a camp for three months. In October 1943, he fled to Sweden after the Danish government resigned and the Nazis declared martial law, which endangered the Jewish population in Denmark. The fact that Bauer was a homosexual – something he was careful to keep to himself – placed him in even further peril should he remain in Germany or in Nazi-occupied Denmark.[3] To protect himself, he formally married the Danish kindergarten teacher Anna Maria Petersen, in June 1943.[4] In Sweden, Bauer founded, along with Willy Brandt, the periodical Sozialistische Tribüne (Socialist Tribune). Bauer returned to Germany in 1949, as the postwar Federal Republic (West Germany) was being established, and once more entered the civil service in the justice system. At first he became director of the district courts, and later the equivalent of a U.S. district attorney, in Braunschweig. In 1956, he was appointed the district attorney in Hessen, based in Frankfurt. Bauer held this position until his death in 1968.

In 1957, thanks to Lothar Hermann, a former Nazi camps prisoner, Bauer relayed information about the whereabouts in Argentina of fugitive Holocaust planner Adolf Eichmann to Israeli Intelligence, the Mossad. Hermann's daughter Sylvia began dating a man named Klaus Eichmann in 1956 who boasted about his father's Nazi exploits, and Hermann alerted Fritz Bauer, at the time prosecutor-general of the Land of Hesse in West Germany. Hermann then tasked his daughter with investigating her new friend's family; she met with Eichmann himself at his house, who said that he was Klaus's uncle. Klaus arrived not long after, however, and addressed Eichmann as "Father".[5] In 1957 Bauer passed the information to Mossad director Isser Harel, who assigned operatives to undertake surveillance, but no concrete evidence was initially found.[6] Bauer did not trust neither Germany's police nor that country's legal system, as he feared that if he had informed them, they would likely have tipped off Eichmann.[7] Thus he decided to turn directly to Israel authorities. Moreover, when Bauer called on the German government in order to make efforts to get Eichmann extradited from Argentina, the German government immediately responded negatively.[8] In 2021 it was revealed that much more instrumental than Hermann to the capture of Eichmann was geologist Gerhard Klammer, who had worked with Eichmann in the early 1950s in a construction company in the Argentinian Tucumán province, who provided Bauer with Eichmann's exact address and a photograph of Eichmann alongside Klammer. Klammer was in contact with the German priest Giselher Pohl and bishop Hermann Kunst, to whom he sent the information with the photograph, from which Klammer's face was ripped. Kunst, in turn, passed the evidences to Bauer. Bauer's sources remained secret, and along with Klammer's recomposed picture were not revealed before 2021.[9]

Mossad's Isser Harel acknowledged the important role Fritz Bauer played in Eichmann's capture, and claimed that he pressed insistently the Israeli authorities to organize an operation to apprehend and deport him to Israel. In Harel book's introduction by Shlomo J. Shpiro, added to the 1997 expanded edition, it is revealed for the first time that Bauer did not act alone, but was discretely helped by Hesse minister-president Georg-August Zinn.[10][11]

Bauer also was active in the postwar efforts to obtain justice and compensation for victims of the Nazi regime. In 1958, he succeeded in getting a class action lawsuit certified, consolidating numerous individual claims in the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials, which opened in 1963.

In 1968, working with German journalist Gerhard Szczesny, Bauer founded the Humanist Union, a human-rights organization. After Bauer's death, the Union donated money to endow the Fritz Bauer Prize. Another organization, the Fritz Bauer Institute, founded in 1995, is a nonprofit organization dedicated to civil rights that focuses on history and the effects of the Holocaust.

Fritz Bauer's work contributed to the creation of an independent, democratic justice system in West Germany, as well as to the prosecution of Nazi war criminals and the reform of the criminal law and penal systems.

Within the postwar German justice system, Bauer was a controversial figure due to his political engagements. He once said, "In the justice system, I live as in exile."

Bauer died in Frankfurt am Main, aged 64. He was found drowned in his bathtub. A post mortem examination found that he had taken alcohol and sleeping tablets.[12][13]

Works[]

- Die Kriegsverbrecher vor Gericht ("War Criminals in Court"), with a postscript by Hans Felix Pfenninger. Neue Internationale Bibliothek, 3. Europa, Zürich 1945.

- Das Verbrechen und Gesellschaft ("Crime and Society"). Reinhardt 1957.

- Sexualität und Verbrechen ("Sexuality and Crime"). Fischer 1963.

- Die neue Gewalt ("The new Oppression"). Verl. d. Zeitschrift Ruf u. Echo 1964.

- Widerstand gegen die Staatsgewalt ("Resistance to State Oppression"). Fischer 1965.

- Die Humanität der Rechtsordnung. Ausgewählte Schriften ("The Human Vales of Legal Process; Selected Documents"). Joachim Perels and Irmtrud Wojak, Campus Verlag, Frankfurt, New York 1998, ISBN 3-593-35841-7.

Biographies[]

- Irmtrud Wojak: Fritz Bauer und die Aufarbeitung der NS-Verbrechen nach 1945. Blickpunkt Hessen, Hessische Landeszentrale für politische Bildung, Nr. 2/2003

- Irmtrud Wojak: Fritz Bauer. Eine Biographie, 1903–1963, Munich: C.H. Beck, 2009, ISBN 3-406-58154-4

- Ilona Ziok: Fritz Bauer – Death By Instalments, Germany, 2010, (film) 110 min.

- Ronen Steinke: Fritz Bauer: oder Auschwitz vor Gericht, Piper, 2013, ISBN 978-3492055901

See also[]

- The People vs. Fritz Bauer, a 2015 German film

- Labyrinth of Lies, a 2014 German film

References[]

- ^ "Humanistische Union: Wir über uns: Geschichte: Geschichtedetail". www.humanistische-union.de.

- ^ Wojak, Irmtrud (2009). Fritz Bauer 1903–1968: eine Biographie. Munich: C.H.Beck. p. 54. ISBN 978-3-406-58154-0.

- ^ "Fritz Bauer's biography does not justify other than a little suspect that his main sexual orientation was of an homosexual type, which at that time could not be openly expressed, unless he wanted to put his political life at stake". Ronen Steinke (2014). "On Fritz Bauer's alleged homosexuality". Neue Justiz (in German): 515.

- ^ STEINKE, RONEN (7 April 2020). Fritz Bauer. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 72f. doi:10.2307/j.ctvzgb8h5. ISBN 978-0-253-04689-5.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- ^ Lipstadt, Deborah E. (2011). The Eichmann Trial. New York: Random House. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-8052-4260-7.

- ^ Cesarani, David (2005) [2004]. Eichmann: His Life and Crimes. London: Vintage. pp. 223–224. ISBN 978-0-09-944844-0.

- ^ The CIA and German Federal Intelligence Service (BND) knew by 1958 that Eichmann was living in Argentina and knew an approximation of his cover name.Shane, Scott. "C.I.A. Knew Where Eichmann Was Hiding, Documents Show". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ Wojak, Irmtrud (2011). Fritz Bauer 1903-1968. Eine Biographie (in German). C. H. Beck, Munich. p. 302. ISBN 978-3406623929.

- ^ "Der Mann der Adolf Eichmann enttarnte (The man who unmasked Adolf Eichmann)" (in German). Retrieved 25 August 2021.

- ^ Harel, Isser (1997). The House on Garibaldi Street. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781315036687.

- ^ "Das haus in der Garibaldi Straße (The house on Garibaldi Street)". Der Spiegel (in German). 6 July 1975. Retrieved 28 August 2021. In this article there was just a hint to Zinn ("Eine hochstehende Persönlichkeit von großer Integrität" - a very important person of great integrity), whose name and role were not clearly revealed before the aforementioned 1997 Shpiro's introduction.

- ^ "Germany finally pays tribute to the first Nazi hunter". The Independent. 28 February 2016.

- ^ Matthias Bartsch (26 July 2016). "Der Mann, der die Nazis jagte". Erst 18 Jahre nach Kriegsende begann in Frankfurt am Main der Prozess gegen die Täter von Auschwitz. Zu verdanken war dies dem hartnäckigen Juristen Fritz Bauer. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fritz Bauer. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Fritz Bauer |

- Fritz Bauer Institute (German)

- Fritz Bauer – Tod auf Raten, Documentary, 2012

- Labyrinth of Lies (German) Im Labyrinth des Schweigens, 2014

- 1903 births

- 1968 deaths

- People educated at Eberhard-Ludwigs-Gymnasium

- People from the Kingdom of Württemberg

- 20th-century German Jews

- Social Democratic Party of Germany politicians

- Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold members

- Jurists from Stuttgart

- Heidelberg University alumni

- Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich alumni

- University of Tübingen alumni

- 20th-century German jurists

- LGBT history in Germany