Gaius Sosius

Gaius Sosius | |

|---|---|

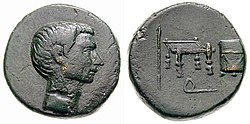

Probable likeness of Sosius (obverse) | |

| Nationality | Roman |

| Occupation | General and politician |

Notable work | Rebuilt the temple of Apollo Sosianus |

| Office | Governor of Syria and Cilicia Consul of Rome (32 BC) Quindecimvir sacris faciundis |

| Children | 2 |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | Mark Antony |

| Years | 38–31 BC |

| Wars | Siege of Jerusalem (37 BC) Sicilian revolt (36 BC) Battle of Actium (31 BC) |

| Awards | Roman triumph (34 BC) |

Gaius Sosius (fl. 39–17 BC) was a Roman general and politician who featured in the wars of the late Republic as a staunch supporter of Mark Antony. He held several important state offices and military commands in Antony's service, and led the military expedition to install Rome's client, Herod, as king of Judea. Sosius became consul in the critical year 32 BC, when the Second Triumvirate lapsed and open conflict erupted between the triumvirs, Antony and Octavian. As consul, Sosius warmly espoused the cause of Antony and vigorously opposed Octavian in the Senate, for which he was forced to flee Rome.

In the ensuing civil war, Sosius was one of Antony's most loyal and important lieutenants. He commanded part of the fleet of Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC. Following the defeat, Sosius was reluctantly pardoned by Octavian, later the emperor Augustus, but was soon fully rehabilitated and integrated into the imperial regime. He appears to have had or acquired significant wealth, rebuilding the namesake temple of Apollo Sosianus in Rome. Presumed descendants of his continued holding the highest offices of state 200 years into imperial times.

Life[]

Background and career (39–32 BC)[]

Gaius Sosius's family probably came from Picenum,[1] and had apparently achieved political prominence only recently. His father, also called Gaius Sosius, was the first recorded senator of the family, having reached praetorian rank by the time of the civil war between Julius Caesar and Pompey.[2][3] The younger Sosius emerged into prominence during the dictatorship of the Second Triumvirate as a devoted supporter of the triumvir Marc Antony.[4] Sometime between 41 and 39 BC,[5] Sosius served as Antony's quaestor[6] and was stationed at the Roman naval base of Zacynthus, one of the Ionian islands west of the Peloponnese, apparently to guard the region from the rebel leader Sextus Pompey, who held Sicily. As per the Pact of Misenum in 39 BC, the Triumvirate agreed to hand the Peloponnese to Sextus, but Antony did not honor this agreement and Sosius remained on guard there at his behest.[7] Among the pact's provisions was also Sosius's designation to the office of consul for the year 32 BC.[8]

During this time, Antony traveled east to reorganize the local provinces and appoint client kings after the region had been unsuccessfully invaded by the Parthian Empire.[9] Sosius accompanied Antony (presumably leaving a detachment back at Zacynthus to guard against Sextus Pompey)[10] and may have been present when the latter besieged Samosata, the capital of King Antiochus of Commagene, who had sided with the Parthians.[11] In 38 BC, Antony appointed Sosius as proconsular governor of Syria and (according to Cassius Dio) Cilicia, in which capacity the latter subdued the rebellious island city of Aradus, the main urban center of northern Phoenicia.[12] Antony then commanded Sosius to depose the Parthian-backed Jewish king Antigonus and replace him with Rome's ally, Herod.[13] Sending two legions ahead to assist Herod before following up with the rest of his troops, Sosius besieged Antigonus at Jerusalem, which he captured after a few months with many civilians killed or enslaved.[14] Antigonus surrendered to the Romans rather than Herod, expecting greater leniency from them.[15] Sosius, for his part, mocked and insulted Antigonus (calling him 'Antigona'), but delivered him unharmed to Antony (who in turn, however, executed him).[16] According to the Jewish historian Josephus, Sosius was dissuaded from allowing his soldiers to plunder the city by Herod's offer of a large gift to the troops.[17]

Sosius celebrated the victory by dedicating a crown of gold to the gods,[18] and was moreover acclaimed as imperator by his troops (with Antony's recognition), which gave him the right to enter Rome in triumph.[19] The ancient historian Cassius Dio recorded a subsequent period of inactivity for Sosius, ostensibly due to fear of arousing Antony's jealousy.[20][i] In late 36 BC, Sosius was in Sicily assisting the other triumvir, Octavian, in mopping up the remaining resistance of the renegade Sextus Pompey.[22] After Octavian dismissed him and other Antonian reinforcements, Sosius returned to Zacynthus,[10] and, in 35 BC, Antony replaced him with Lucius Munatius Plancus as governor of Syria.[23] On 3 September 34 BC he was back in Rome celebrating his triumph over the Jews.[24] After this, he seems to have remained in the city, looking after Antony's interests there while awaiting his own consulship in 32 BC, as the Triumvirate neared its legal end and tensions between Octavian and Antony increased to the point of civil war.[25] During this time, apparently to further commemorate his triumph, Sosius began rebuilding the temple of Apollo in the Campus Martius, adding statues of Apollo and the Niobids which he took from Seleucia in Cilicia back when he was governor.[26] This may have been a gesture against Octavian, who had already vowed to build a new temple of the same deity elsewhere in the city.[27]

Consulship and civil war (32–31 BC)[]

The Second Triumvirate, which had ruled the Roman Republic since 42 BC, was to legally expire in either the beginning or the end of 32 BC, after which the triumvirs would become private citizens.[28] In the years leading to this moment, the relationship between the triumvirs collapsed, prompting a propaganda war and culminating in Antony divorcing Octavian's sister to marry his long-time lover, the Egyptian queen Cleopatra.[29] The two consuls-designate for this critical year, Gaius Sosius and Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, were both partisans of Antony, which gave the latter a strong constitutional advantage over his rival.[30] Domitius and Sosius brought with them dispatches by Antony which included an offer to ceremonially resign his dictatorial powers, as well as a request for the Roman People to ratify his conquest of Armenia and several land grants for his children with Cleopatra in the east – the so-called Donations of Alexandria.[31] They, however, refused to publish it, despite pressure from Octavian, probably because they feared it would be used as ammunition for enemy propaganda. Also contained in Antony's dispatch were several incriminating denunciations against Octavian, who in turn likewise prevented their publication.[32]

As result of these deliberations, the consuls did not read Antony's dispatch before the Senate, withholding it from the public altogether.[33] Upon assuming office, on 1 January, Sosius instead (with a boldness not shared by the more cautious Domitius) delivered a violent harangue to the Senate, in which he heaped praise upon Antony and denounced Octavian. He also put forward a motion against the latter, but this was promptly vetoed by a tribune of the plebs.[34][ii] Upon hearing of this attack, Octavian, who had been away from Rome, returned to the city and stormed into the senate, summoning a new session and surrounding the building with soldiers carrying concealed weapons. Taking a seat between the two consuls in defiance of their authority, Octavian denounced Sosius's conduct and promised to produce evidence that would decisively incriminate Antony.[37] Not daring to speak up, the consuls and up to hundreds of other sympathetic senators fled the city in protest to join Antony and Cleopatra at Ephesus in Asia Minor, where they formed a makeshift Senate in opposition to that at Rome.[38] Back in the capital, Sosius and Domitius were promptly stripped of the consulship,[39] and their absence left the initiative in the propaganda war with Octavian,[40] who, by illegally seizing Antony's will, obtained the compromising information needed to finally procure a Roman declaration of war on Egypt.[41]

In the ensuing war, Sosius was one of the main commanders of Antony's fleet. Towards the end of August 31 BC, Sosius, under cover of fog, routed a squadron of Octavian's fleet led by Lucius Tarius Rufus, but was then driven back by enemy reinforcements led by Marcus Agrippa, which cost Sosius the victory and the life of his ally, King Tarcondimotus of Cilicia.[42] As Antony's situation worsened and many deserted his cause, Sosius remained loyal to him, alongside only two (known) others among the senators of consular rank.[43][iii] He commanded the left wing of Antony's fleet at the decisive battle of Actium on 2 September.[46] Sosius's wing at some point began to crumble, Antony and Cleopatra fled away onto safety (to later commit suicide), and the battle was lost.[47] Sosius survived the defeat and spent some time in hiding, but was eventually detected and brought before Octavian. The latter was not, apparently, inclined to spare this rabid Antonian, but did so at the intercession of one of his own admirals at Actium, Lucius Arruntius.[48][iv]

Later life[]

Sosius seems to have undertaken no further military service in his life after Actium.[50] He returned to Rome and completed his reconstruction of the temple of Apollo, which thus became known as the temple of Apollo Sosianus, and which may have been dedicated or inaugurated on the birthday of Octavian, who became the emperor Augustus.[51] That he could afford to do so suggests he was or became a wealthy man.[52] He was fully rehabilitated and integrated into the Augustan regime, which is seen by his inclusion among the priestly quindecimviri sacris faciundis who supervised the Saecular Games in 17 BC.[53] Sosius appears on the Ara Pacis within the College of the quindecimviri sacris faciundis.[54] Sosius's last known mention is of his presence at the trial of one "Corvus", a professor of rhetoric alleged to have had harmed the state for his comments supposedly condoning birth control. This event has been tentatively dated, by conjecture, to AD 6, by which time Sosius would have been nearing 80 years old.[55]

It is unknown if Sosius had sons, but two daughters are known: Sosia, wife of Sextus Nonius Quinctilianus (consul in AD 8), and Sosia Galla, wife of Gaius Silius (consul AD 13). Based on the name Galla, the mother might have been an Asinia, a Nonia or an Aelia.[56] However, the name reappears with Q. Sosius Senecio (consul in 99 and 107)[57] and Saint Sossius (275-305 AD).

Notes[]

- ^ Dio says the same of Sosius's predecessor as governor, Ventidius. Reinhold considers the explanation implausible and suggests Dio derived it from a source hostile to Antony.[21]

- ^ The major source for the chronology of these events, Cassius Dio, says Sosius's speech against Octavian took place on the first day of the month, without specifying which month it was. The context and language of Dio's narrative points to January, but February has also been suggested, on basis that time must be considered to allow for the negotiations over Antony's dispatch, and that Sosius, as consul posterior, would not have acted while his more cautious colleague, Domitius, held fasces (took precedence) in January.[35] However, the negotiations could also have taken place between Sosius's attack and Octavian's intervention, and Sosius did not have to hold fasces to be allowed to speak.[36]

- ^ Publius Canidius Crassus and Lucius Gellius Poplicola. Domitius, Sosius's colleague in the consulship, deserted.[44] At Actium, Sosius's rank gave him the right to command one of the wings, where the most important combat was expected to take place.[45]

- ^ Syme, on the other hand, suggested Sosius's peril and rescue "may have been artfully staged" as a way to advertise Octavian's clemency (clementia).[49]

Citations[]

- ^ Syme, pp. 200, 498, 563.

- ^ Brill's New Pauly, Sosius.

- ^ Broughton, pp. 154, 258, 387, 621.

- ^ Fluss, col. 1177; Shipley, p. 73; Reinhold, p. 53.

- ^ Shipley, p. 77; Syme, p. 223 (note 3).

- ^ Brill's New Pauly, Sosius 1.2.

- ^ Grant, pp. 39–40; RPC, p. 263.

- ^ Gray, p. 22.

- ^ Broughton, pp. 383, 387, 391, 393, 400.

- ^ a b Grant, p. 40.

- ^ Reinhold, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Fluss, col. 1177; Broughton, p. 393; Reinhold, p. 53.

- ^ Reinhold, pp. 53, 54.

- ^ Reinhold, p. 54; CAH, pp. 28, 747.

- ^ Reinhold, pp. 54, 55.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities, xiv. 16. 2, 4, Jewish War, i. 18. 2, 3.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities, xiv. 16. 3, Jewish War, i. 18. 3.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities, xiv. 16. 4, Jewish War, i. 18. 3.

- ^ Shipley, p. 80.

- ^ Reinhold, p. 58; Broughton, pp. 397–398; Grant, p. 40.

- ^ Reinhold, pp. 50, 58.

- ^ Grant, pp. 40, 393, 394; Broughton, pp. 402–403.

- ^ Broughton, pp. 408, 409.

- ^ Fluss, col. 1178.

- ^ Shipley, pp. 80–81, 84.

- ^ Fluss, coll. 1177, 1179; Shipley, pp. 73, 82–85; Reinhold, p. 81; Grant, p. 40.

- ^ Shipley, p. 84; CAH, p. 47.

- ^ Shipley, pp. 74, 75, 81; Gray, pp. 18–19, 22.

- ^ Broughton, p. 417; Gray, pp. 25–26; Syme, pp. 276–277.

- ^ Reinhold, pp. 87–88; Syme, pp. 279–280; CAH, p. 68.

- ^ Broughton, p. 417; Reinhold, p. 77; Gray, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Syme, p. 278; Gray, p. 16; Reinhold, p. 77.

- ^ Syme, p. 278; Gray, p. 16.

- ^ Gray, p. 15; Shipley, p. 81; Syme, p. 278.

- ^ Reinhold, pp. 88–89; Gray, p. 17.

- ^ Lange, p. 61.

- ^ Syme, p. 278; Gray, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Syme, pp. 278–280; Reinhold, pp. 85, 89, 90; Lange, pp. 61, 62.

- ^ Syme, p. 279; Reinhold, p. 89.

- ^ CAH, p. 50.

- ^ Syme, p. 282; Gray, p. 15; Reinhold, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Fluss, col. 1179; Reinhold, p. 104; CAH, p. 56.

- ^ Syme, pp. 295–296.

- ^ Syme, p. 296.

- ^ Pelling, p. 281.

- ^ Reinhold, p. 113.

- ^ Reinhold, p. 114.

- ^ Fluss, col. 1179; Reinhold, p. 113.

- ^ Syme, pp. 297, 299; Reinhold, p. 124.

- ^ Fluss, col. 1179; Syme, p. 327.

- ^ Fluss, coll. 1179, 1180; Lange, p. 133.

- ^ Grant, pp. 11, 41, 89 (and notes); Fluss, col. 1179.

- ^ Reinhold, pp. 104, 124; Syme, pp. 349–350 (note 3).

- ^ Gaius Stern, Women Children and Senators on the Ara Pacis Augustae

- ^ Cramer, pp. 170–171 (and note 59).

- ^ Gaius Stern, Women Children and Senators on the Ara Pacis Augustae, University of California Berkeley dissertation 2006, page 353, n.88

- ^ Some Arval Brethren by Ronald Syme.

References[]

- Brill's New Pauly: Jens Bartels & Werner Eck, "Sosius", ISBN 978-90-04-12259-8.

- Broughton, T. Robert S. (1952). The Magistrates of the Roman Republic Volume II: 99 B.C.–31 B.C. New York: American Philological Association.

- CAH – Alan K. Bowman; Edward Champlin & Andrew Lintott, eds. (1996). The Cambridge Ancient History X: The Augustan Empire, 43 B.C.–A.D. 69 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-26430-8.

- Cramer, Frederick H. (1945). "Bookburning and Censorship in Ancient Rome: A Chapter from the History of Freedom of Speech". Journal of the History of Ideas. 6 (2): 157–196. JSTOR 2707362.

- Fluss, Max, "Sosius 2", Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft, volume III A.1, columns 1176–1180 (Stuttgart, 1927).

- Grant, Michael (1969) [1946]. From Imperium to Auctoritas: A Historical Study of Aes Coinage in the Roman Empire, 49 B.C.–A.D. 14. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-07457-6.

- Gray, E.W. (1975). "The crisis in Rome at the beginning of 32 B.C." (PDF). The Proceedings of the African Classical Associations. Rhodesia. 13: 15–29. ISSN 0555-3059.

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, xiv. 15, 16; The Jewish War, i. 17, 18

- Lange, Carsten Hjort (2009). Res Publica Constituta: Actium, Apollo and the Accomplishment of the Triumviral Assignment. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-17501-3.

- Pelling, C.B.R., ed. (1988). Plutarch: Life of Antony. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24066-2.

- Reinhold, Meyer (1988). From Republic to Principate: An Historical Commentary on Cassius Dio's Roman History Books 49–52 (36–29 B.C.). Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press. ISBN 1-55540-112-0.

- RPC – Burnett, Andrew; Michel Amandry & Pere Pau Ripollès (1992). Roman Provincial Coinage volume I: From the death of Caesar to the death of Vitellius (44 BC–AD 69); Part I: Introduction and Catalogue. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 0-7141-0871-5.

- Shipley, Frederick W. (1930). "C. Sosius: His Coins, his Triumph and his Temple of Apollo" (PDF). Language and Literature. New series. 3: 73–87. ISSN 0963-9470.

- Syme, Ronald (1939). The Roman Revolution. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Archived.CS1 maint: postscript (link)

- 1st-century BC Roman governors of Syria

- 1st-century BC Roman consuls

- Ancient Roman generals

- Priests of the Roman Empire

- Quindecimviri sacris faciundis

- Roman governors of Cilicia

- Roman quaestors

- Roman triumphators

- Sosii