Gellan gum

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names

Gum gellan; E418; [D-Glc(β1→4)D-GlcA(β1→4)D-Glc(β1→4)L-Rha(α1→3)]n

| |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.068.267 |

| EC Number |

|

| E number | E418 (thickeners, ...) |

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Gellan gum is a water-soluble anionic polysaccharide produced by the bacterium Sphingomonas elodea (formerly Pseudomonas elodea based on the taxonomic classification at the time of its discovery).[1] The gellan-producing bacterium was discovered and isolated by the former Kelco Division of Merck & Company, Inc. in 1978 from the lily plant tissue from a natural pond in Pennsylvania. It was initially identified as a substitute gelling agent at significantly lower use level to replace agar in solid culture media for the growth of various microorganisms.[2] Its initial commercial product with the trademark as Gelrite gellan gum, was subsequently identified as a suitable agar substitute as gelling agent in various clinical bacteriological media.[3]

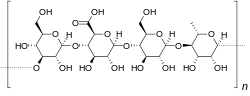

Chemical structure[]

The repeating unit of the polymer is a tetrasaccharide, which consists of two residues of D-glucose and one of each residues of L-rhamnose and D-glucuronic acid. The tetrasaccharide repeat has the following structure:

[D-Glc(β1→4)D-GlcA(β1→4)D-Glc(β1→4)L-Rha(α1→3)]n

Gellan gum products are generally put into two categories, low acyl and high acyl depending on number of acetate groups attached to the polymer. The low acyl gellan gum products form firm, non-elastic, brittle gels, whereas the high acyl gellan gum forms soft and elastic gels.[4]

Microbiological gelling agent[]

Gellan gum is initially used as a gelling agent, alternative to agar, in microbiological culture. It is able to withstand 120 °C heat. It was identified as an especially useful gelling agent in culturing thermophilic microorganisms.[5] One needs only approximately half the amount of gellan gum as agar to reach an equivalent gel strength, though the exact texture and quality depends on the concentration of the divalent cations present. Gellan gum is also used as gelling agent in plant cell culture on Petri dishes, as it provides a very clear gel, facilitating light microscopical analyses of the cells and tissues. Although advertised as being inert, experiments with the moss Physcomitrella patens have shown that choice of the gelling agent—agar or Gelrite—does influence phytohormone sensitivity of the plant cell culture.[6]

Food science[]

As a food additive, gellan gum was first approved for food use in Japan (1988). Gellan gum has subsequently been approved for food, non-food, cosmetic and pharmaceutical uses by many other countries such as US, Canada, China, Korea and the European Union etc. It is widely used as a thickener, emulsifier, and stabilizer. It has E number E418. It was an integral part of the now defunct Orbitz soft drink. It is used as the gelling agent, as an alternative to gelatin, in the manufacture of vegan varieties of "gum" candies.

It is used in plant-based milks to keep plant protein suspended in the milk.[7] Gellan has also become popular in haute cuisine, and in particular in molecular gastronomy and other scientifically-informed schools of cooking, to make flavorful gels; British chef Heston Blumenthal and American chef Wylie Dufresne are generally considered to be the earliest chefs to incorporate gellan into high-end restaurant cooking, but other chefs have since adopted the innovation.[8]

Gellan gum, when properly hydrated, can be used in ice cream and sorbet recipes that behave as a fluid gel after churning. The benefit of using gellan gum is that the ice cream or sorbet can be set in a dish of flaming alcohol without actually melting.[9]

Production[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2013) |

Gellan was discovered and developed as a commercial biogum hydrocolloid product by Kelco, then a division of Merck & Co. In the United States, Kelco was responsible for obtaining food approval for gellan gum worldwide. In other markets that are fond of innovative food ingredients such as Japan, the process for obtaining food approval has been undertaken by local food and beverage manufacturers. Kelco, now the CP Kelco family of companies owned by J.M. Huber Corporation historically, produced the majority of food grade gellan gum. However, since the entry into the segment of Royal DSM, the Dutch science and food nutrition conglomerate, users of food grade gellan gum now procure from 2 high quality suppliers. Chinese suppliers have also been increasingly aggressive in gellan gum production. However, the lack of consistent quality production, adherence to stringent food grade requirements and lack of a strong technical and application support means that such gellan gum is primarily destined for use in personal care or household care applications.

Pure gellan gum is one of the most expensive hydrocolloids. Its cost in use, however, is competitive with the other much lower priced hydrocolloids.[clarification needed]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Narendra B. Vartak, Chi Chung Lin, Joseph M. Cleary, Matthew J. Fagan, Milton H. Saier, Jr. (1995). "Glucose metabolism in Sphingomonas elodea': pathway engineering via construction of a glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase insertion mutant". Microbiology. 141 (9): 2339–2350. doi:10.1099/13500872-141-9-2339. PMID 7496544.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Kang K.S., Veeder G.T., Mirrasoul P.J., Kaneko T., Cottrell I.W. (1982) Agar-like polysaccharide produced by a Pseudomonas species: Production and basic properties. Applied & Environmental Microbiology, 43, 1086-1091.

- ^ Shungu D, Valiant M, Tutlane V, Weinberg E, Weissberger B, Koupal L, Gadebusch H, Stapley E.: GELRITE as an Agar Substitute in Bacteriological Media, Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983 Oct;46(4):840-5.

- ^ Gao, Chang Hong (2016). "Unique rheology of high acyl gellan gum and its potential applications in enhancement of petroleum production". Journal of Petroleum Exploration and Production Technology. 6 (4): 743–747. doi:10.1007/s13202-015-0212-8. S2CID 101046679.

- ^ Chi Chung Lin, L. E. Casida, Jr. (1984): GELRITE as a gelling agent in media for the growth of thermophilic microorganisms. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 47, 427–429

- ^ Birgit Hadeler, Sirkka Scholz, Ralf Reski (1995): Gelrite and agar differently influence cytokinin-sensitivity of a moss. Journal of Plant Physiology 146, 369–371

- ^ "CP Kelco Introduces KELCOGEL HS-B Gellan Gum. - Free Online Library". Thefreelibrary.com. 2005-02-22. Retrieved 2012-05-23.

- ^ "Fluid Gels: A Culinary History". ChefSteps. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- ^ The Fat Duck Cookbook, Heston Blumenthal, ISBN 978-0-7475-9737-7, p238-241, "Flaming sorbet"

External links[]

- Dea, Ian C M (1989). "Industrial polysaccharides" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 61 (7): 1315–1322. doi:10.1351/pac198961071315. S2CID 195819313.

- Polysaccharides

- Microbiological gelling agent

- Natural gums

- Edible thickening agents

- Sphingomonas

- E-number additives