Genovese crime family

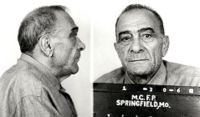

Vito Genovese, boss from 1957 to 1969 | |

| Founded | c. 1890s |

|---|---|

| Founder | Giuseppe Morello |

| Named after | Vito Genovese |

| Founding location | New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Years active | c. 1890s–present |

| Territory | Primarily New York City, with additional territory in Upstate New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Connecticut, South Florida, Las Vegas, and Los Angeles. |

| Ethnicity | Italians as "made men" and other ethnicities as associates |

| Membership (est.) | 250–300 made members and 1,000+ associates (2004)[1] |

| Activities | Racketeering, murder, labor union infiltration, extortion, illegal gambling, drug trafficking, loansharking, bookmaking, truck hijacking, fraud, prostitution, pornography, bribery, and assault |

| Allies | Bonanno crime family Colombo crime family Gambino crime family Lucchese crime family Bufalino crime family Buffalo crime family Chicago Outfit Cleveland crime family DeCavalcante crime family New Orleans crime family Patriarca crime family Philadelphia crime family Pittsburgh crime family |

| Rivals | Various gangs in New York City, including their allies |

The Genovese crime family (pronounced [dʒenoˈveːze, -eːse]) is one of the "Five Families" that dominate organized crime activities in New York City and New Jersey as part of the American Mafia. They have generally maintained a varying degree of influence over many of the smaller mob families outside New York, including ties with the Philadelphia, Patriarca, and Buffalo crime families.

The current "family" was founded by Charles "Lucky" Luciano and was known as the Luciano crime family from 1931 to 1957, when it was renamed after boss Vito Genovese. Originally in control of the waterfront on the West Side of Manhattan and the Fulton Fish Market, the family was run for years by "the Oddfather", Vincent "the Chin" Gigante, who feigned insanity by shuffling unshaven through New York's Greenwich Village wearing a tattered bath robe and muttering to himself incoherently to avoid prosecution.

The Genovese family is the oldest and the largest of the "Five Families". Finding new ways to make money in the 21st century, the family took advantage of lax due diligence by banks during the housing bubble with a wave of mortgage frauds. Prosecutors say loan shark victims obtained home equity loans to pay off debts to their mob bankers. The family found ways to use new technology to improve on illegal gambling, with customers placing bets through offshore sites via the Internet.

Although the leadership of the Genovese family seemed to have been in limbo after the death of Gigante in 2005, they appear to be the most organized and powerful family in the U.S., with sources believing that Liborio "Barney" Bellomo is the current boss of the organization.[2] Unique in today's Mafia, the family has benefited greatly from members following "Omertà," a code of conduct emphasizing secrecy and non-cooperation with law enforcement and the justice system. While many mobsters from across the country have testified against their crime families since the 1980s, the Genovese family has had only ten members turn state's evidence in its history.[3]

History[]

Origins[]

The Genovese crime family originated from the Morello gang of East Harlem, the first Mafia family in New York City.[4] In 1892, Giuseppe Morello arrived in New York from the village of Corleone, Sicily, Italy. Morello's half brothers Nicholas, Vincenzo, Ciro, and the rest of his family joined him in New York the following year. The Morello brothers formed the 107th Street Mob and began dominating the Italian neighborhood of East Harlem, parts of Manhattan, and the Bronx.

One of Giuseppe Morello's strongest allies was Ignazio "the Wolf" Lupo, a mobster who controlled Manhattan's Little Italy. In 1903, Lupo married Morello's half-sister, uniting both organizations. The Morello-Lupo alliance continued to prosper in 1903, when the group began a major counterfeiting ring with powerful Sicilian mafioso Vito Cascioferro, printing $5 bills in Sicily and smuggling them into the US.

New York police detective Joseph Petrosino, later assassinated while in Sicily seeking evidence to permit the deportation of Morello and other mafiosi, began investigating the Morello family's counterfeiting operation, the barrel murders, and the black hand extortion letters. On November 15, 1909, Morello, Lupo, and others were arrested on counterfeiting charges. In February 1910, Morello and Lupo were sentenced to twenty-five and thirty years in prison, respectively.[5]

In 1910 the Lomonte Brothers, cousins of Morello, ran East Harlem until 1915. Fortunato Lomonte was shot and killed in 1914 on East 108th st. Tomasso Lomonte and cousin Rose Lomonte were both shot and killed in 1915 on East 116th st.

Mafia-Camorra War[]

As the Morello family increased in power and influence, bloody territorial conflicts arose with other Italian gangs in New York. The Morellos had an alliance with Giosue Gallucci, a prominent East Harlem businessman and Camorrista with local political connections. On May 17, 1915, Gallucci was murdered in a power struggle between the Morellos and the Neapolitan Camorra organization, which consisted of two Brooklyn gangs run by Pellegrino Morano and Alessandro Vollero. The fight over Gallucci's rackets became known as the Mafia-Camorra War.

After months of fighting, Morano offered a truce. A meeting was arranged at a Navy Street cafe owned by Vollero. On September 7, 1916, Nicholas Morello and his bodyguard Charles Ubriaco were ambushed and killed upon arrival by five members of the Camorra gang.[6] In 1917, Morano was charged with Morello's murder after Camorrista Ralph Daniello implicated him in the murder. By 1918, law enforcement had sent many Camorra members to prison, decimating the Camorra in New York and ending the war. Many of the remaining Camorra members joined the Morello family.

The Morellos now faced stronger rivals than the Camorra. With the passage of Prohibition in 1920 and the ban of alcohol sales, the family regrouped and built a lucrative bootlegging operation in Manhattan. In 1920, both Morello and Lupo were released from prison and Brooklyn Mafia boss Salvatore D'Aquila ordered their murders. This is when Giuseppe "Joe" Masseria and Rocco Valenti, a former Brooklyn Camorra, began to fight for control of the Morello family.[7]

On December 29, 1920, Masseria's men murdered Valenti's ally, Salvatore Mauro. Then, on May 8, 1922, the Valenti gang murdered Vincenzo Terranova. Masseria's gang retaliated killing Morello member Silva Tagliagamba. On August 11, 1922, Masseria's men murdered Valenti, ending the conflict, as Masseria took over the Morello family.[8]

The Castellammarese era[]

During the mid-1920s, Masseria continued to expand his bootlegging, extortion, loansharking, and illegal gambling rackets throughout New York. To operate and protect these rackets, he recruited many ambitious young mobsters, including future heavyweights Charles "Lucky" Luciano, Frank Costello, Joseph "Joey A" Adonis, Vito Genovese, and Albert Anastasia. Luciano soon became a top aide in Masseria's organization.

By the late 1920s, Masseria's main rival was boss Salvatore Maranzano, who had come from Sicily to run the Castellammarese clan. Their rivalry eventually escalated into the bloody Castellammarese War. As the war turned against Masseria, Luciano, seeing an opportunity to switch allegiance, decided to eliminate him in 1931. In a secret deal with Maranzano, Luciano agreed to engineer Masseria's death in return for taking over his rackets and becoming Maranzano's second-in-command.[9]

Adonis had joined the Masseria faction, and when Masseria heard about Luciano's betrayal, he approached Adonis about killing Luciano. However, Adonis instead warned Luciano about the murder plot.[10]

On April 15, 1931, Masseria was killed at Nuova Villa Tammaro, a Coney Island restaurant. While they played cards, Luciano allegedly excused himself to the bathroom, with the gunmen reportedly being Anastasia, Genovese, Adonis, and Benjamin "Bugsy" Siegel;[11] Ciro "The Artichoke King" Terranova drove the getaway car, but legend has it that he was too shaken up to drive away and had to be shoved out of the driver's seat by Siegel.[12][13] With Maranzano's blessing, Luciano became his lieutenant and took over Masseria's gang, ending the Castellammarese War.[9]

With Masseria gone, Maranzano reorganized the Italian-American gangs in New York into Five Families headed by Luciano, Joe Profaci, Tommy Gagliano, Vincent Mangano, and himself. Maranzano called a meeting of crime bosses in Wappingers Falls, New York, where he declared himself capo di tutti capi ("boss of all bosses").[9] Maranzano also whittled down the rival families' rackets in favor of his own. Luciano appeared to accept these changes, but was merely biding his time before removing Maranzano.[14] Although Maranzano was slightly more forward-thinking than Masseria, Luciano had come to believe that he was even more power-hungry and hidebound than Masseria had been.[9]

By September 1931, Maranzano realized Luciano was a threat, and hired Vincent "Mad Dog" Coll, an Irish gangster, to kill him.[9] However, Tommy Lucchese alerted Luciano that he was marked for death.[9] On September 10, Maranzano ordered Luciano, Genovese, and Costello to come to his office at the 230 Park Avenue in Manhattan. Convinced that Maranzano planned to murder them, Luciano decided to take pre-emptive action.[15] He sent to Maranzano's office four Jewish gangsters, secured with the aid of Siegel and Meyer Lansky, whose faces were unknown to Maranzano's people.[16] Disguised as government agents, two of the gangsters disarmed Maranzano's bodyguards. The other two, aided by Lucchese, stabbed Maranzano multiple times before shooting him.[17][18]

Luciano and the Commission[]

After Maranzano's murder, Luciano called a meeting in Chicago with various bosses, where he proposed a Commission to serve as the governing body for organized crime.[19] Designed to settle all disputes and decide which families controlled which territories, the Commission has been called Luciano's greatest innovation.[9] Luciano's goals with the Commission were to quietly maintain his own power over all the families, and to prevent future gang wars; the bosses approved the idea of the Commission.[5]

The Commission's first test came in 1935, when they ordered Dutch Schultz to drop his plans to murder Special Prosecutor Thomas E. Dewey. Luciano argued that an assassination of Dewey would precipitate a massive law enforcement crackdown. An enraged Schultz vowed to kill Dewey anyway and walked out of the meeting.[20]

Anastasia, now the leader of Murder, Inc., approached Luciano with information that Schultz had asked him to stake out Dewey's apartment building on Fifth Avenue. Upon hearing the news, the Commission held a discreet meeting to discuss the matter. After six hours of deliberations, the Commission ordered Lepke Buchalter to eliminate Schultz.[21][22] On October 23, 1935, before he could kill Dewey, Schultz was shot in a tavern in Newark, New Jersey, and succumbed to his injuries the following day.[23][24]

On May 13, 1936, Luciano's pandering trial began.[25] Dewey prosecuted the case that Eunice Carter had built against Luciano, accusing him of being part of a massive prostitution ring known as "the Combination".[26] During the trial, Dewey exposed Luciano for lying on the witness stand through direct quizzing and records of telephone calls; Luciano also had no explanation for why his federal income tax records claimed he made only $22,000 a year, while he was obviously a wealthy man.[9]

Dewey's case against Luciano on the prostitution charges actually leveled in the indictment, on the other hand, rested on much shakier ground: first on the testimony of Joe Bendix, who was discredited by his own testimony as well as that of others, and then later on the testimony of three prostitutes, whom Dewey rewarded by either paying for a trip to Europe after the trial or arranging for lucrative film and magazine deals.[27] All three witnesses subsequently recanted their testimony.

On June 7, 1936, Luciano was convicted on 62 counts of compulsory prostitution.[28] On June 18, he was sentenced to thirty to fifty years in state prison, along with David Betillo and others.[29][30]

Luciano continued to run his crime family from prison, relaying his orders through Genovese, his acting boss. However, in 1937, Genovese fled to Naples to avoid an impending indictment for murder in New York.[31] Luciano appointed Costello, his consigliere, as the new acting boss and overseer of Luciano's interests.

During World War II, federal agents came to Luciano for help in preventing enemy sabotage on the New York waterfront and other activities. Luciano agreed to help, in return for a pardon from the State of New York, made contingent on Luciano's deportation to Italy.[27] In reality Luciano provided insignificant assistance to the Allied cause.[citation needed]

After the end of the war, the arrangement with Luciano became public knowledge. To prevent further embarrassment, the government followed through on its plans to deport Luciano on condition that he never return to the U.S. In 1946, Luciano was taken from prison and deported to Italy, where he died in 1962.[32]

The Prime Minister[]

From May 1950 to May 1951, the U.S. Senate conducted a large-scale investigation of organized crime, commonly known as the Kefauver Hearings, chaired by Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee. Costello was convicted of contempt of the Senate and sentenced to eighteen months in prison.[33] Kefauver concluded that New York politician Carmine DeSapio was assisting the activities of Costello, and that Costello had become influential in decisions made by the Tammany Hall political machine. DeSapio admitted to having met Costello several times, but insisted that "politics was never discussed".[34]

In 1952, the federal government began proceedings to strip Costello of his U.S. citizenship and he was indicted for evasion of $73,417 in income taxes between 1946 and 1949. He was sentenced to five years in prison and fined $20,000.[33] In 1954, Costello appealed the conviction and was released on $50,000 bail; from 1952 to 1961, he was in and out of half a dozen federal and local prisons and jails, his confinement interrupted by periods when he was out on bail pending determination of appeals.[35][33]

The return of Genovese[]

Costello ruled for twenty peaceful years, but his quiet reign ended when Genovese was extradited from Italy to New York. During his absence, Costello demoted Genovese from underboss to caporegime, leaving Genovese determined to take control of the family. Soon after his arrival in the U.S., Genovese was acquitted of the 1936 murder charge that had driven him into exile.[36] Free of legal entanglements, he started plotting against Costello with the assistance of Mangano family underboss Carlo Gambino.

On May 2, 1957, Luciano mobster Vincent "the Chin" Gigante shot Costello in the side of the head as Costello returned to his apartment. Gigante's aim proved errant, however, and Costello survived the attack with no more than a flesh wound.[37] Costello claimed he could not identify his attacker; Gigante was later acquitted when prosecuted for the shooting.

Months later, Anastasia, the boss of the Mangano family and a powerful ally of Costello's, was murdered by Gambino's gunmen at the Park Central Hotel in Manhattan. With Anastasia's death, Carlo Gambino seized control of the Mangano family. Fearing for his life and isolated after the shootings, Costello quietly retired and surrendered control of the Luciano family to Genovese.[38]

Having taken control of what was renamed the Genovese crime family in 1957, Genovese decided to organize a Mafia conference to legitimize his new position. Held at mobster Joseph "Joe the Barber" Barbara's estate in Apalachin, New York, the Apalachin meeting attracted over 100 mobsters from around the nation. However, local law enforcement stumbled upon the meeting and quickly surrounded the estate. As the meeting broke up, the police stopped a car driven by Russell Bufalino, whose passengers included Genovese and three other men, at a roadblock as they left the estate.[39][40][41] Mafia leaders were chagrined by the public exposure and bad publicity from the Apalachin meeting, and generally blamed Genovese for the fiasco. All those apprehended were fined, up to $10,000 each, and given prison sentences ranging from three to five years, but all the convictions were overturned on appeal in 1960.[40]

Wary of Genovese gaining more power in the Commission, Gambino used the Apalachin meeting as an excuse to move against his former ally. Gambino, Luciano, Costello, and Lucchese allegedly lured Genovese into a drug-dealing scheme that ultimately resulted in his conspiracy indictment and conviction. In 1959, Genovese was sentenced to fifteen years in prison on narcotics charges.[42] Genovese, who was the most powerful boss in New York, had been effectively eliminated as a rival by Gambino.[43]

The Valachi Hearings[]

Genovese soldier Joe Valachi was convicted of narcotics violations in 1959 and sentenced to fifteen years in prison.[44] Valachi's motivations for becoming a government informant had been the subject of some debate; Valachi claimed to be testifying as a public service and to expose a powerful criminal organization that he had blamed for ruining his life, but it is possible he was hoping for government protection as part of a plea bargain in which he was sentenced to life imprisonment instead of the death penalty for a 1962 murder.[44]

While serving his sentence for heroin trafficking, Valachi came to fear that Genovese, also serving a sentence on the same charge, had ordered his murder.[45] On June 22, 1962, using a pipe left near some construction work, Valachi bludgeoned an inmate to death whom he had mistaken for Joseph DiPalermo, a Mafia member he believed had been contracted to kill him.[44] After time with FBI handlers, Valachi came forward with a story of Genovese giving him a kiss on the cheek, which he took as a "kiss of death."[46][47][48] A $100,000 bounty for Valachi's death had been placed by Genovese.[49]

Soon after, Valachi decided to cooperate with the US Justice Department.[50] In October 1963, he testified before Arkansas Senator John L. McClellan's Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the US Senate Committee on Government Operations, known as the Valachi hearings, stating that the Italian-American Mafia actually existed, the first time a member had acknowledged its existence in public.[51][52] Valachi's testimony was the first major violation of omertà, breaking his blood oath. He is credited with popularization of the term cosa nostra.[53]

Although Valachi's disclosures never led directly to the prosecution of any Mafia leaders, he provided many details of history of the Mafia, operations, and rituals; aided in the solution of several unsolved murders; and named many members and the major crime families. The trial exposed American organized crime to the world through Valachi's televised testimony.[26]

Front bosses and the ruling panels[]

After Genovese was sent to prison in 1959, the family leadership secretly established a "Ruling Panel" to run the family in his absence. This first panel included acting boss Thomas "Tommy Ryan" Eboli, underboss Gerardo "Jerry" Catena, and Catena's protégé Philip "Benny Squint" Lombardo. After Genovese died in 1969, Lombardo was named his successor.

However, the family appointed a series of "front bosses" to masquerade as the official family boss. The aim of these deceptions was to protect Lombardo by confusing law enforcement as to who was the true leader of the family.

In the late 1960s, Gambino lent $4 million to Eboli for a drug scheme in an attempt to gain control of the Genovese family. When Eboli failed to pay back his debt, Gambino, with Commission approval, had him murdered in 1972.[54][55][56]

After Eboli's death, Genovese capo and Gambino ally Frank "Funzi" Tieri was appointed as the new front boss. In reality, the Genovese family created a new ruling panel to run the organization. This second panel consisted of Catena, Lombardo, and Michele "Big Mike" Miranda. In 1981, Tieri became the first Mafia boss to be convicted under the new RICO Act and died in prison later that year.[57]

After Tieri's imprisonment, the family reshuffled its leadership. The capo of the Manhattan faction, Anthony "Fat Tony" Salerno, became the new front boss. Lombardo, the de facto boss of the family, soon retired and Gigante, the triggerman on the failed Costello hit, took actual control of the family.[58]

In 1985, Salerno was convicted in the Mafia Commission Trial and sentenced to 100 years in federal prison.[59] In 1986, shortly after Salerno's conviction, his longtime right-hand man, Vincent "The Fish" Cafaro, turned informant and told the FBI that Salerno had been the front boss for Gigante. Cafaro also revealed that the Genovese family had been keeping up this ruse since 1969.[60][61]

After the 1980 murder of Philadelphia boss Angelo "Gentle Don" Bruno, Gigante and Lombardo began manipulating the rival factions in the war-torn Philadelphia family. They finally gave their support to Philadelphia mobster Nicodemo "Little Nicky" Scarfo, who in return gave the Genovese mobsters permission to operate in Atlantic City in 1982.[58]

The Oddfather[]

Gigante built a vast network of bookmaking and loansharking rings, and from extortion of garbage, shipping, trucking, and construction companies seeking labor peace or contracts from carpenters', Teamsters, and laborers' unions, including those at the Javits Center, as well as protection payoffs from merchants at the Fulton Fish Market.[62] Gigante also had influence in the Feast of San Gennaro in Little Italy, running illegal gambling operations, extorting payoffs from vendors, and pocketing thousands of dollars donated to a neighborhood church—until a crackdown in 1995 by New York City officials.[62] During Gigante's tenure as boss of the Genovese family, after the imprisonment of John Gotti in 1992, Gigante came to be known as the figurehead capo di tutti capi, the "Boss of All Bosses", despite the position being abolished since 1931 with the murder of Salvatore Maranzano.[63]

Gigante was reclusive, and almost impossible to capture on wiretaps, speaking softly, eschewing the phone, and even at times whistling into the receiver.[64] He almost never left his home unoccupied because he knew FBI agents would sneak in and plant a bug.[64] Genovese members were not allowed to mention Gigante's name in conversations or phone calls; when they had to mention him, members would point to their chins or make the letter "C" with their fingers.[62][65]

On May 30, 1990, Gigante was indicted along with other members of four of the Five Families for conspiring to rig bids and extort payoffs from contractors on multimillion-dollar contracts with the New York City Housing Authority to install windows.[66] Gigante attended his arraignment in pajamas and bathrobe, and due to his defense stating that he was mentally and physically impaired, legal battles ensued for seven years over his competence to stand trial.[62] In June 1993, Gigante was indicted again, charged with sanctioning the murders of six mobsters and conspiring to kill three others, including Gotti.[67][62]

At sanity hearings in March 1996, Sammy "The Bull" Gravano, former underboss of the Gambino family, who became a cooperating witness in 1991,[68] and Alphonse "Little Al" D'Arco, former acting boss of the Lucchese family, testified that Gigante was lucid at top-level Mafia meetings and that he had told other gangsters that his eccentric behavior was a pretense.[62] Gigante's lawyers presented testimony and reports from psychiatrists stating that, from 1969 to 1995, Gigante had been confined twenty-eight times in hospitals for treatment of hallucinations and that he suffered from "dementia rooted in organic brain damage".[62]

In August 1996, Judge Eugene Nickerson of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York ruled that Gigante was mentally competent to stand trial; he pleaded not guilty and had been free for years on $1 million bail.[62] Gigante had a cardiac operation in December 1996.[62] On June 25, 1997, Gigante's trial started, which he attended in a wheelchair.[69]

On July 25, after almost three days of deliberations, the jury convicted Gigante of conspiring in plots to kill other mobsters and of running rackets as head of the Genovese family but acquitted him of seven counts of murder.[70] Prosecutors stated that the verdict finally established that Gigante was not mentally ill as his lawyers and relatives had long maintained.[70] On December 18, 1997, Gigante was sentenced to twelve years in prison and fined $1.25 million by Judge Jack B. Weinstein, a lenient sentence due to Gigante's "age and frailty", who declared that Gigante had been "...finally brought to bay in his declining years after decades of vicious criminal tyranny".[71]

While in prison, Gigante maintained his role as boss of the Genovese family while other mobsters were entrusted to run its day-to-day activities. Gigante relayed orders to the family through his son, Andrew, who visited him in prison.[72][73][62]

On January 23, 2002, Gigante was indicted with several other mobsters, including Andrew, on obstruction of justice charges due to a him causing a seven-year delay in his previous trial by feigning insanity.[74][75] Several days later, Andrew was released on $2.5 million bail.[76] On April 7, 2003, the day the trial began, Prosecutor Roslynn R. Mauskopf had planned to play tapes showing Gigante "fully coherent, careful, and intelligent," running criminal operations from prison, but when Gigante pled guilty to obstruction of justice,[77][78] Judge I. Leo Glasser sentenced him to an additional three years in prison.[62][79] Mauskopf stated, "The jig is up...Vincent Gigante was a cunning faker, and those of us in law enforcement always knew that this was an act...The act ran for decades, but today it's over."[77] On July 25, 2003, Andrew Gigante was sentenced to two years in prison and fined $2.5 million for racketeering and extortion.[80]

Gigante died on December 19, 2005, at the Medical Center for Federal Prisoners in Springfield, Missouri.[62] His funeral and burial were held four days later, on December 23, at Saint Anthony of Padua Church in Greenwich Village, largely in anonymity.[64]

Current position and leadership[]

After Gigante's death, the leadership of the Genovese family went to capo Daniel "Danny the Lion" Leo, who was apparently running the day-to-day activities of the family by 2006.[81] That same year, Cirillo was reportedly promoted to consigliere behind bars and Mangano was released from prison. By 2008, the family administration was believed to be whole again.[82]

In March of that year, Leo was sentenced to five years in prison for loansharking and extortion. Former acting consigliere Lawrence "Little Larry" Dentico was leading the New Jersey faction of the family until convicted of racketeering in 2006; he was released from prison in 2009. In December 2008, Liborio Bellomo was paroled after serving twelve years; what role he plays in the Genovese hierarchy is open to speculation, but he likely has had a major say in the running of the family once his tight parole restrictions expired.

A March 2009 article in the New York Post claimed Leo was still acting boss despite his incarceration. It also estimated that the Genovese family consists of about 270 "made" members.[83]

The family maintains power and influence in New York, New Jersey, Atlantic City and Florida. It is recognized as the most powerful Mafia family in the U.S., a distinction brought about by their continued devotion to secrecy.[2] According to the FBI, many Genovese family associates do not know the names of family leaders or even other associates, making it difficult for investigators to gather intelligence about the family's current status.[84]

In 2016, Eugene "Rooster" Onofrio, who is believed to be a capo largely active in Little Italy and Connecticut, was accused of operating a large multimillion-dollar enterprise that ran bookmaking offices, scammed medical businesses, and smuggled cigarettes and guns. He was also alleged to have run a loanshark operation from Florida to Massachusetts.[85] Other members of his reputed crew pleaded guilty to extortion and other crimes.[86] Gerald Daniele, an associate, was sentenced to two years in prison in March 2018.[87] On April 10, 2018, Ralph Santaniello, suspected of being a Genovese acting capo, was sentenced to five years in prison for extorting $20,000 from Craig Morel, the owner of one of the biggest towing and scrap-metal companies in Massachusetts, including threatening his life and assaulting him.[88][89][90] Morel managed to negotiate the extortion price from $100,000 to $20,000. Associate Giovanni "Johnny" Calabrese was sentenced to 3 years in prison.[91]

In October 2017, thirteen Genovese and Gambino associates and soldiers were sentenced after being indicted following an NYPD operation in December 2016. Dubbed "Shark Bait", the investigation focused on a large-scale illegal gambling and loansharking ring. Prosecutors claimed 76-year-old Genovese soldier Salvatore DeMeo was in charge of the operation and had generated several million dollars from the enterprise. Soldier Alex Conigliaro was sentenced to four months in jail and four months house arrest in late October 2017, with a fine of $5,000, after admitting that he supervised and financed a $14,000-per-week illegal bookmaking and sports betting operation between 2011 and 2014.[92][93] Genovese associates Gennaro Geritano and Mario Leonardi were allegedly partners in selling untaxed cigarettes in New York, alleged to have sold over 30,000 packs.[94]

According to the FBI, the Genovese family has not had an official boss since Gigante's death.[95] Law enforcement considers Leo to be the acting boss, Mangano the underboss, and Cirillo the consigliere. The family is known for placing top capos in leadership positions to help the administration run day-to-day activities. At present, capos Bellomo, Muscarella, Cirillo, and Dentico hold the greatest influence within the family and play major roles in its administration.[84] The Manhattan and Bronx factions, the traditional powers in the family, still exercise that control today.

On January 10, 2018, five members and associates, including Gigante's son Vincent Esposito, were arrested and charged with racketeering, conspiracy, and several counts of related offenses by the NYPD and FBI.[96] The charges include extortion, labor racketeering conspiracy, fraud and bribery. Genovese associate and Brooklyn-based United Food and Commercial Workers officer Frank Cognetta was also charged.[97] Union official and associate Vincent D'Acunto Jr. was also involved and allegedly acted on behalf of Esposito to pass along threat messages and to also collect extortion money from the union, in particular from Vincent Fyfe, the president of a wine liquor and distillery union in Brooklyn. Fyfe was forced to pay $10,000 per year to keep his $300,000-a-year union job, which he achieved through the influence of the Genovese family. The labor union infiltration was alleged to have taken place for at least sixteen years. Esposito allegedly extorted several other union officials and an insurance agent. At his home during a warranted search, authorities recovered an unregistered handgun, $3.8 million in cash, brass knuckledusters, and a handwritten list of American Mafia members.[98]

Esposito was granted bail for almost $10 million in April 2018, and pled not guilty.[99] In April, 2019, Esposito pled guilty to conspiring to commit racketeering offenses with members and associates of the Genovese family.[100] He was sentenced in July, 2019 to two years in prison.[101]

Historical leadership[]

Boss (official and acting)[]

- c. 1890s–1909 — Giuseppe "the Clutch Hand" Morello — imprisoned

- 1909–1916 — Nicholas "Nick Morello" Terranova — murdered on September 7, 1916

- 1916–1920 — Vincenzo "Vincent" Terranova — stepped down becoming underboss

- 1920–1922 — Giuseppe "the Clutch Hand" Morello — stepped down becoming underboss to Masseria

- 1922–1931 — Giuseppe "Joe the Boss" Masseria — murdered on April 15, 1931

- 1931–1946 — Charles "Lucky" Luciano — imprisoned in 1936, deported to Italy in 1946

- Acting 1936–1937 — Vito Genovese — fled to Italy in 1937 to avoid murder charge

- Acting 1937–1946 — Frank "the Prime Minister" Costello — became official boss after Luciano's deportation

- 1946–1957 — Frank "the Prime Minister" Costello — resigned in 1957 after Genovese-Gigante assassination attempt[102][103]

- 1957–1969 — Vito "Don Vito" Genovese — imprisoned in 1959, died in prison in 1969

- Acting 1959–1962 — Anthony "Tony Bender" Strollo — disappeared in 1962

- Acting 1962–1965 — Thomas "Tommy Ryan" Eboli — became front boss

- Acting 1965–1969 — Philip "Benny Squint" Lombardo — became the official boss

- 1969–1981 — Philip "Benny Squint" Lombardo[104] — retired in 1981, died of natural causes in 1987

- 1981–2005 — Vincent "Chin" Gigante[104] — imprisoned in 1997, died in prison on December 19, 2005[105]

- Acting 1989–1996 — Liborio "Barney" Bellomo — promoted to street boss

- Acting 1997–1998 — Dominick "Quiet Dom" Cirillo — suffered heart attack and resigned

- Acting 1998–2005 — Matthew "Matty the Horse" Ianniello — resigned when indicted in July 2005

- Acting 2005–2008 — Daniel "Danny the Lion" Leo[106] — imprisoned 2008–2013

- 2010–present — Liborio "Barney" Bellomo

Street boss (front boss)[]

The position of "front boss" was created by boss Philip Lombardo in efforts to divert law enforcement attention from himself. The family maintained this "front boss" deception for the next 20 years. Even after government witness Vincent Cafaro exposed this scam in 1988, the Genovese family still found this way of dividing authority useful. In 1992, the family revived the front boss post under the title of "street boss." This person served as day-to-day head of the family's operations under Gigante's remote direction.

- 1965–1972 — Thomas "Tommy Ryan" Eboli — murdered in 1972[104]

- 1972–1974 — Carmine "Little Eli" Zeccardi[104] — disappeared (presumed killed) in 1977

- 1974–1980 — Frank "Funzi" Tieri[104] — indicted under RICO statutes and resigned, died in 1981

- 1981–1987 — Anthony "Fat Tony" Salerno[104] — imprisoned in 1987, died in prison in 1992

- 1992–1996 — Liborio "Barney" Bellomo — imprisoned from 1996 to 2008

- 1998–2001 — Frank Serpico[72][73] – in 2001 was indicted,[107] in 2002 died of cancer[108]

- 2001–2002 — Ernest Muscarella — indicted in 2002[107]

- 2002–2006 — Arthur "Artie" Nigro — indicted in 2006

- 2010–2013 — Peter "Petey Red" DiChiara — stepped down

- 2013–2014 — Daniel "Danny" Pagano — indicted August 2014

- 2014–2015 — Peter "Petey Red" DiChiara — became consigliere

- 2015–present — Michael "Mickey" Ragusa[109]

Underboss (official and acting)[]

- 1903–1909 — Ignazio "the Wolf" Lupo — imprisoned

- 1910–1916 — Vincenzo "Vincent" Terranova — became boss

- 1916–1920 — Ciro "the Artichoke King" Terranova — stepped down

- 1920–1922 — Vincenzo "Vincent" Terranova — murdered on May 8, 1922

- 1922–1930 — Giuseppe "Peter the Clutch Hand" Morello — murdered on August 15, 1930

- 1930–1931 — Joseph Catania — murdered on February 3, 1931[110]

- 1931 — Charles "Lucky" Luciano — became boss April 1931

- 1931–1936 — Vito Genovese — promoted to acting boss in 1936, fled to Italy in 1937

- 1937–1951 — Guarino "Willie" Moretti — murdered in 1951

- 1951–1957 — Vito Genovese[111] — second time as underboss

- 1957–1970 — Gerardo "Jerry" Catena — also boss of the New Jersey faction; jailed from 1970 to 1975[112]

- 1970–1972 — Thomas "Tommy Ryan" Eboli — also served as front boss, murdered in 1972[104]

- 1972–1976 — Frank "Funzi" Tieri — also served as front boss[104]

- 1976–1980 — Anthony "Fat Tony" Salerno[104] — promoted to front boss in 1980

- 1980–1981 — Vincent "Chin" Gigante — promoted to official boss

- 1981–1987 — Saverio "Sammy" Santora[104] — died of natural causes

- 1987–2017 — Venero "Benny Eggs" Mangano — imprisoned in 1993, released December 2006, died August 18, 2017, of natural causes.

- Acting 1990–1997 — Michael "Mickey Dimino" Generoso — imprisoned from 1997 to 1998[113]

- Acting 1997–2003 — Joseph Zito

- Acting 2003–2005 — John "Johnny Sausage" Barbato — imprisoned from 2005 to 2008

- 2017–present — Ernest "Ernie" Muscarella

Consigliere (official and acting)[]

- 1931–1937 — Frank Costello — promoted to acting boss in 1937

- 1937–1957 — "Sandino" — mysterious figure mentioned once by Valachi

- 1957–1972 — Michele "Mike" Miranda — retired in 1972

- 1972–1976 — Anthony "Fat Tony" Salerno — promoted to underboss in 1976[104]

- 1976–1978 — Antonio "Buckaloo" Ferro[104]

- 1978–1980 — Dominick "Fat Dom" Alongi[104][114]

- 1980–1990 — Louis "Bobby" Manna[104] — imprisoned in 1990

- Acting 1989–1990 — James "Little Guy" Ida — became official consigliere

- 1990–1997 — James "Little Guy" Ida — imprisoned in 1997

- 1997–2008 — Lawrence "Little Larry" Dentico[113] — imprisoned from 2005 to 2009, retired.

- Acting 2005–2008 — Dominick "Quiet Dom" Cirillo – became official consigliere.

- 2008–2015 – Dominick "Quiet Dom" Cirillo — reportedly stepped down

- 2015–2018 – Peter "Petey Red" DiChiara – died on March 2, 2018

- 2018–present – Unknown

Messaggero[]

Messaggero – The messaggero (messenger) functions as liaison between crime families. The messenger can reduce the need for sit-downs, or meetings, of the mob hierarchy, and thus limit the public exposure of the bosses.

- 1957–1969 — Michael "Mike" Genovese — the brother of Vito Genovese.[115][116]

- 1997–2002 — Andrew V. Gigante — the son of Vincent Gigante, indicted 2002

- 2002–2005 — Mario Gigante[117][118]

Administrative capos[]

If the official boss dies, goes to prison, or is incapacitated, the family may assemble a ruling committee of capos to help the acting boss, street boss, underboss, and consigliere run the family, and to divert attention from law enforcement.

- 1997–2001 — (four-man committee) — Dominick "Quiet Dom" Cirillo, Lawrence "Little Larry" Dentico, John "Johnny Sausage" Barbato and Alan "Baldie" Longo — in 2001 Longo was indicted

- 2001–2005 — (four-man committee) — Dominick Cirillo, Lawrence Dentico, John Barbato and Anthony "Tico" Antico — in April 2005 all four were indicted[119]

- 2005–2010 — (three-man committee) — Tino "The Greek" Fiumara (died 2010)[120] the other two are unknown.

Current family members[]

Administration[]

- Boss – Liborio "Barney" Bellomo – born January 8, 1957. He served in the 116th Street Crew of Saverio "Sammy Black" Santora and was initiated in 1977. His father was a soldier and close to Anthony "Fat Tony" Salerno. In 1990, Kenneth McCabe, then-organized crime investigator for the United States attorney's office in Manhattan, identified Bellomo as "acting boss" of the crime family following the indictment of Vincent Gigante in the "Windows Case".[121][122] In June 1996, Bellomo was indicted on charges of extortion, labor racketeering and for ordering the deaths of Ralph DeSimone in 1991 and Antonio DiLorenzo in 1988; DeSimone was found shot 5 times in the trunk of his car at LaGuardia Airport and DiLorenzo was shot and killed in the backyard of his home.[123] Since around 2016, Bellomo was recognised, most likely, to be official boss of the Genovese family.

- Street Boss – Michael "Mickey" Ragusa – born June 22, 1965. Ragusa is a former soldier in Bellomo's Harlem/Bronx crew. In January 2002, Ragusa was indicted, along with acting boss Ernest Muscarella, capo Charles Tuzzo, members Liborio Bellomo, Thomas Cafaro, Pasquale Falcetti and associate Andrew Gigante, for the infiltration of the International Longshoreman's Association.[124][125]

- Underboss – Ernest "Ernie" Muscarella – former acting boss and former capo of the 116th Street crew. In January 2002, Muscarella serving as acting boss of the family was indicted, along with capo Charles Tuzzo, members Liborio Bellomo, Thomas Cafaro, Pasquale Falcetti, Michael Ragusa and associate Andrew Gigante, for the infiltration of the International Longshoreman's Association.[124] On January 11, 2008, Muscarella was released from prison.[126] On April 16, 2019, Muscarella was identified as the Underboss of the Genovese family during a lawfully recorded conversation between Gambino family soldier Vincent Fiore and Gambino family associate Mark Kocaj.[127]

- Consigliere – Unknown

Caporegimes[]

The Bronx faction

- Pasquale "Uncle Patty" Falcetti – capo of the 116th Street Crew with operations in the Bronx and Manhattan. In September 2014, Falcetti was sentenced to 30 months in prison for loansharking.[128][129] During Falcetti's trial former Genovese family associate Anthony Zoccolillo testified against Falcetti and claimed that Falcetti gave him a $34,000 loan for a marijuana trafficking operation.[128] On January 13, 2017, Falcetti was released from prison.[130] On July 10, 2017, Falcetti was observed by a law enforcement surveillance team meeting with Gambino crime family capo Andrew Campos in the Pelham Bay diner.[127][131]

- Joseph G. "Joe D" Denti, Jr. – (sometimes spelled Dente) is a capo operating in the Bronx and New Jersey. His father Joseph Denti Sr. was a Bronx loan shark during the 1970s before moving in the early 1990s to Beverly Hills.[132] In 1996, his father died from a heart attack and his funeral was attended by many famous Hollywood figures, including Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci, Cher and Cathy Moriarty.[132] In 2000, Denti Jr. and Chris Cenaitempo became suspects in a police investigation after Chris's brother John Cenatiempo was identified by the police as an accomplice of Christopher Rocancourt, a man who robbed homes in the Hamptons.[132] On December 5, 2001, Denti Jr. along with capo Rosario Gangi, capo Pasquale Parrello and 70 other associates were indicted in Manhattan on racketeering charges.[133][134] The charges were brought against Denti Jr. and the others after it had been revealed that an undercover NYPD detective had infiltrated Parrello's Arthur Avenue crew.[133][135] On April 29, 2009, Denti Jr. was released from federal prison.[136] On March 16, 2016, Denti Jr. along with Joseph Giardina, Ralph Perricelli Jr., and Heidi Francavilla were indicted and charged with defrauding investors in medical ventures out of $350,000.[137]

- (Imprisoned) Pasquale "Patsy" Parrello – born in 1945. He is a capo operating in the Bronx, who owns a restaurant on Arthur Ave called Pasquale's Rigoletto Restaurant. In 2004, Parrello was found guilty of loansharking and embezzlement along with capo Rosario Gangi, and was sentenced to 88 months.[138] Parrello was released from prison on April 23, 2008.[139][140] In August 2016, Parrello was indicted along with Genovese family capo Conrad Ianniello and Genovese family acting capo Eugene O'Norfio and Philadelphia family boss Joseph Merlino and forty two other mobsters on gambling and extortion charges.[141] In May 2017, he pled guilty to three counts of conspiracy to commit extortion and was sentenced to seven years in federal prison in September 2017. Prosecutors at his trial alleged that in June 2011 he ordered two of his soldiers to break the kneecaps of a man who annoyed female patrons at his restaurant.[142][143] Parrello is currently imprisoned with a projected release date of July 22, 2022.[144]

- Daniel "Danny" Pagano – capo operating from the Bronx, Westchester, Rockland and New Jersey. During the 1980s, Pagano was involved in the bootleg gasoline scheme with Russian mobsters.[145] In 2007, Pagano was released after serving 105 months in prison.[146] On July 10, 2015 Pagano was sentenced to 27 months in prison on racketeering conspiracy charges.[147][148] He was released from prion on August 29, 2017.[149]

- Daniel "Danny the Lion" Leo – a former member of the Purple Gang of East Harlem in the 1970s. In the late 1990s, Leo joined Vincent Gigante's circle of trusted capos. With Gigante's death in 2005, Leo became acting boss. In 2008, Leo was sentenced to five years in prison on loansharking and extortion charges. In March 2010, Leo received an additional 18 months in prison on racketeering charges and was fined $1.3 million. He was released on January 25, 2013.[150][151]

Manhattan faction

- Conrad Ianniello – capo operating in Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island, Connecticut, Long Island, New Jersey, Springfield and Florida. On April 18, 2012, Ianniello was indicted along with members of his crew and was charged with illegal gambling and conspiracy.[152][153] The conspiracy charge dates back to 2008, when Ianniello along with Robert Scalza and Ryan Ellis tried to extort vendors at the annual Feast of San Gennaro in Little Italy.[152] Conrad Ianniello is related to Robert Ianniello, Jr., who is the nephew to Matthew Ianniello and the owner of Umberto's Clam House.[154] In August 2016 Ianniello was indicted along with Genovese family capo Pasquale Parrello and Genovese family acting capo Eugene O'Norfio and Philadelphia family boss Joseph Merlino and forty two other mobsters on gambling and extortion charges.[141]

- John Brescio – capo operating in Manhattan. Brescio owns "Lombardi's", a Manhattan based pizzeria, which he runs with his step-son, Michael Giammarino. Brescio and Giammarino were denied a request to open a Lombardi's location inside of Parx Casino in Bensalem Township in Pennsylvania.[155]

Brooklyn faction

- John "Johnny Sausage" Barbato – capo and former driver of Venero Mangano, he was involved in labor and construction racketeering with capos from the Brooklyn faction. Barbato was imprisoned in 2005 on racketeering and extortion charges, and released in 2008.[156][157]

Queens faction

- Anthony "Rom" Romanello – capo operating from Corona Avenue in Corona, Queens[158] Romanello took over Anthony Federici's old crew. In January 2012, he pleaded guilty to illegal gambling after the cooperating witness died from a heart attack before testifying in the case.[158]

New Jersey faction

- Silvio P. DeVita – Sicilian-born capo operating in Essex County. He is currently believed to be controlling Newark. He has prior convictions of first-degree murder, robbery and several other offenses. DeVita has also been barred from visiting any casino in New Jersey.[159]

Soldiers[]

New York

- Eugene "Rooster" Onofrio – a mobster from East Haven, Connecticut. O'Nofrio served as acting capo of the "Mulberry Street crew" in Manhattan's Little Italy and acting capo of the "Springfield, Massachusetts, crew".[141] In 2016 Onofrio was indicted along with Genovese family capo's Pasquale Parrello and Conrad Ianniello and Philadelphia family boss Joseph Merlino and Springfield gangsters Ralph Santaniello and Francesco Depergola and 40 other mobsters on gambling and extortion charges.[141]

- Ralph "the Undertaker" Balsamo (born 1971) – a mobster with operations in the Bronx, Manhattan and Westchester. His nickname "the Undertaker" comes from him owning funeral homes in the Bronx. In 2007, Balsamo pled guilty to narcotics trafficking, firearms trafficking, extortion, and union-related fraud and was sentenced to 97 months in prison.[160][161] On March 8, 2013 Balsamo was released from prison. In August 2016, Balsamo was indicted along with 45 other members from other crime families.[141] Balsamo was held in detention until trial.[162] He was released from prison on July 23, 2018.[163]

- Dominick "Quiet Dom" Cirillo – former capo and former trusted aide to boss Vincent Gigante. Cirillo belonged to the West Side Crew and was known as one of the Four Doms; capos Dominick "Baldy Dom" Canterino, Dominick "The Sailor" DiQuarto and Dominick "Fat Dom" Alongi. Cirillo served as acting boss from 1997 to 1998, but resigned due to heart problems. In 2003, Cirillo became acting boss, resigned in 2006 due to his imprisonment on loansharking charges. In August 2008, Cirillo was released from prison.

- Alan "Baldie" Longo - former capo of a Brooklyn crew who formerly served under "Allie Shades" Malangone and ran rackets out of a social club that he owned in Brooklyn. Longo was involved in stock fraud and white-collar crimes in Manhattan and Brooklyn. On April 25, 2001, Longo was indicted on racketeering charges, along with Colombo acting boss Alphonse Persico, based on the work of undercover informant Michael D'Urso. Longo was convicted and sentenced to 11 years.[164] He was released on November 24, 2010.[165]

- Anthony "Tico" Antico – former capo involved in labor and construction racketeering in Brooklyn and Manhattan. In 2005, Antico and capos John Barbato and Lawrence Dentico were convicted of extortion charges. In 2007, he was released from prison.[166][167] On March 6, 2010, Antico was charged with racketeering in connection with the 2008 robbery and murder of Staten Island jeweler Louis Antonelli.[168] He was acquitted of murder charges, but found guilty of racketeering. He was released from prison on June 12, 2018.[169]

- Lawrence "Little Larry" Dentico – former capo operating in South Jersey and Philadelphia. Dentico was consigliere in the late 1990s through the 2000s, when he was imprisoned on extortion, loansharking and racketeering charges. He was released from prison on May 12, 2009.[170][171]

- Albert "Kid Blast" Gallo – former capo operating in Brooklyn neighborhoods of Carroll Gardens, Red Hook, and Cobble Hill and parts of Staten Island. In the mid-1970s, Gallo and Frank Illiano transferred from the Gallo crew of the Colombo crime family to the Genovese family. Gallo's co-capo Illiano died of natural causes in 2014.

- Rosario "Ross" Gangi – former capo operating in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and New Jersey. Gangi was involved in extortion activities at Fulton Fish Market. He was released from prison on August 8, 2008.[172][173]

- James "Jimmy from 8th Street" Messera – former capo of the Little Italy Crew operating in Manhattan and Brooklyn. In the 1990s, Messera was involved in extorting the Mason Tenders union and was imprisoned on racketeering charges.[174][175] He was released from prison on December 12, 1995.[176]

- Alphonse "Allie Shades" Malangone – former capo operating in Manhattan and Brooklyn. Malangone during the 1990s, controlled gambling, loansharking, waterfront rackets and extorting the Fulton Fish Market. He also controlled several private sanitation companies in Brooklyn through Kings County Trade Waste Association and Greater New York Waste Paper Association. Malagone was arrested in 2000 along with several Genovese and Gambino family members for their activities in the private waste industry.[177][178]

- Louis DiNapoli – soldier with his brother Vincent DiNapoli's 116th Street crew.

- Anthony "Tough Tony" Federici – former capo in the Queens. Federici is the owner of a restaurant in Corona, Queens. In 2004, Federici was honored by Queens Borough President Helen Marshall for his community service.[179] Federici has since passed on his illicit mob activities to Anthony Romanello.[158]

- John "Little John" Giglio (born April 11, 1958) – also known as "Johnny Bull" is a soldier involved in loansharking.[180]

- Joseph Olivieri – soldier, operating in the 116th Street Crew under capo Louis Moscatiello. Olivieri has been involved in extorting carpenters unions and is tied to labor racketeer Vincent DiNapoli.[181] He was convicted of perjury and was released from Philadelphia CCM on January 13, 2011.[182][183]

- Charles Salzano – a soldier released from prison in 2009 after serving 37 months on loansharking charges.[161]

- Carmine "Pazzo" Testa — a soldier heavily involved in firearm trafficking along with union fraud, money laundering, narcotic trafficking and illegal gambling charges. He pled guilty to firearm trafficking and has served 72 months with a 5,000 dollar fine.

- Ronald Belliveau – soldier, he was formerly a member of the Greenwich Village crew along with Vincent Gigante, It is unknown whether he is still active.

- Augustino "Crazy Augie" Cataldo (born January 16, 1943 - October 31st, 2020) former capo operating in Brooklyn and Staten Island. Augie was heavily involved with the Fulton Fish Market with his blood relatives. Augie is the first cousin of Genovese Capo Carmine Romano. Augie is the father of Genovese soldier Pete "Scarface" Cataldo, who is believed to run Laborers Local 731 located in New York. Augie opened a hit comedy club called "Grampas Comedy Club" with TV star Al Lewis (actor) as the front. The comedy club was known to be the headquarters for Cataldo.

- Pete "Scarface" Cataldo - Son of Genovese capo Augustino "Crazy Augie" Cataldo. Pete is a current and strong soldier in the Genovese crime family and is heavily involved in the unions. Pete took over his fathers crew when he deceased last year. Pete is known to run Local 731.

New Jersey

- (Imprisoned) Michael "Mikey Cigars" Coppola – former capo of the "Fiumara-Coppola crew",[184] although he is currently imprisoned, Coppola is still seen by law enforcement and experts as a leading captain in the New Jersey faction. He is currently serving his time at the United States Penitentiary, Atlanta for two counts of racketeering and his projected release date is March 4, 2024.[185]

- Anthony "Tony D." Palumbo – is a former acting capo in the New Jersey faction.[186] Palumbo was promoted acting boss of the New Jersey faction by close ally and acting boss Daniel Leo. In 2009, Palumbo was arrested and charged with racketeering and murder along Daniel Leo and others.[186][187][188] In August 2010 Palumbo pled guilty to conspiracy murder charges.[189] He was sentenced to 10 years in prison and was released on November 22, 2019.[190]

- Stephen Depiro – former acting capo of the "Fiumara-Coppola crew". Depiro was overseeing the illegal operations in the New Jersey Newark/Elizabeth Seaport[191] before Fiumara's death in 2010. It is unknown if Depiro still holds this position.

Associates[]

New Jersey

- Frank "Frankie Ariana" DiMattina – an associate convicted January 6, 2014, on extortion and a firearms charge and sentenced to 6 years in prison.[192]

Other territories[]

The Genovese family operates primarily in the New York City area; their main rackets are illegal gambling and labor racketeering.

- New York City – The Genovese family operates in all five boroughs of New York as well as in Suffolk, Westchester, Rockland, and Orange Counties in the New York suburbs. The family controls many businesses in the construction, trucking and waste hauling industries. It also operates numerous illegal gambling, loansharking, extortion, and insurance rackets. Small Genovese crews or individuals have operated in Albany, Delaware County, and Utica. The Buffalo, Rochester and Utica crime families or factions traditionally controlled these areas. The family also controls gambling in Saratoga Springs.[193]

- Connecticut – The Genovese family has long operated trucking and waste hauling rackets in New Haven, Connecticut. In 2006, Genovese acting boss Matthew "Matty the Horse" Ianniello was indicted for trash hauling rackets in New Haven and Westchester County, New York. In 1981, Gustave "Gus" Curcio and his brother were indicted for the murder of Frank Piccolo, a member of the Gambino crime family.[194][195]

- Massachusetts – Springfield, Massachusetts has been a Genovese territory since the family's earliest days. The most influential Genovese leaders from Springfield were Salvatore "Big Nose Sam" Curfari, Francesco "Frankie Skyball" Scibelli, Adolfo "Big Al" Bruno, and Anthony Arillotta (turned informant 2009).[196] In Worcester, Massachusetts, the most influential capos were Frank Iaconi and Carlo Mastrototaro. In Boston, Massachusetts, the New England or Patriarca crime family from Providence, Rhode Island has long dominated the North End of Boston, but has been aligned with the Genovese family since the Prohibition era. In 2010, the FBI convinced Genovese mobsters Anthony Arillotta and Felix L. Tranghese to become government witnesses.[3][197] They represent only the fourth and fifth Genovese made men to have cooperated with law enforcement.[3] The government used Arillotta and Tranghese to prosecute capo Arthur "Artie" Nigro and his associates for the murder of Adolfo "Big Al" Bruno.[197][198]

- Florida – The family is active in South Florida

Family crews[]

- 116th Street Crew – led by Pasquale "Uncle Patty" Falcetti (operates in the East Bronx)

- Greenwich Village Crew – (former crew of Vincent Gigante ) (crew operates in Greenwich Village in Lower Manhattan)

- Broadway Mob – (operated in Manhattan)

- Genovese crime family New Jersey faction – (crew operates in New Jersey)

Former members[]

- Dominick "Fat Dom" Alongi–former member of Vincent Gigante's Greenwich Village Crew.[199]

- Salvatore "Sammy Meatballs" Aparo – a former acting capo. His son Vincent is also a made member of the Genovese family.[200] In 2000, Aparo, his son Vincent, and Genovese associate Michael D'Urso met with Abraham Weider, the owner of an apartment complex in Flatbush, Brooklyn.[201] Weider wanted to get rid of the custodians union (SEIU Local 32B-J) and was willing to pay Aparo $600,000, but Aparo's associate D'Urso was an FBI informant and had recorded the meeting.[202] In October 2002, Aparo was sentenced to five years in federal prison for racketeering.[203] On May 25, 2006, Aparo was released from prison.[204] Aparo died on May 12, 2017, at the age of 87.

- Michael A. "Tona" Borelli - was a New Jersey mobster and former acting co-capo of Tino Fiumara's crew, along with Lawrence Ricci. Borelli controlled construction and illegal gambling rackets in NJ, and formerly oversaw the family's activities in the Teamsters.[205] On March 21, 2020, Borelli died.[206]

- Ludwig "Ninni" Bruschi – former capo operating in South Jersey Counties of Ocean, Monmouth, Middlesex, and North Jersey Counties of Hudson, Essex, Passaic and Union. Bruschi was indicted in June 2003 and paroled in April 2010.[207] On April 19, 2020, Bruschi died.[208]

- Vincent "Vinny" DiNapoli – soldier and former capo with the 116th Street Crew. DiNapoli was heavily involved in labor racketeering and had reportedly earned millions of dollars from extortion, bid rigging and loansharking rackets. DiNapoli dominated the N.Y.C. District Council of Carpenters and used them to extort other contractors in New York. DiNapoli's brother, Joseph DiNapoli, is the former consigliere of the Lucchese crime family.[209][210]

- Dominick "Dom The Sailor" DiQuarto – former member of Vincent Gigante's Greenwich Village Crew.[199]

- Giuseppe Fanaro – was a member of the Morello family, who was involved in the Barrel murder of 1903.[211] In November 1913, Fanaro was murdered by members of the Lomonte and Alfred Mineo's gangs.[212]

- Federico "Fritzy" Giovanelli – soldier who was heavily involved in loansharking, illegal gambling and bookmaking in the Queens/Brooklyn area. Giovanelli was charged with the January 1986 killing of Anthony Venditti, an undercover NYPD detective, but was acquitted. One known soldier in Giovanelli's crew was Frank "Frankie California" Condo. In 2001, Giovanelli worked with soldier Ernest "Junior" Varacalli in a car theft ring. On January 19, 2018, Giovanelli died at the age of 84.[213]

- Joseph N. "Pepe" LaScala – former New Jersey capo operating from Hudson County waterfronts cities of Bayonne and Jersey City. LaScala had been Angelo Prisco's acting capo before he took over the crew.[113] In May 2012, LaScala and other members of his crew were arrested and charged with illegal gambling in Bayonne.[214][215] LaScala died on February 3, 2019, at the age of 87.[216]

- Rosario "Saro" Mogavero – A hitman by the age of 15,[217] Mogavero was a powerful capo and close ally of Vito Genovese.[218] He was the vice president of the International Longshoreman's Association until his arrest for extortion and drug dealing in 1953.[219][220] Mogavero controlled gambling, loan sharking and drug smuggling along the Lower East Side of Manhattan waterfront in the 1950s and 1960s along with Tommy "Ryan" Eboli, Michael Clemente and Carmine "The Snake" Persico.[221]

- Arthur "Artie" Nigro – former member who served as the family's Street Boss from 2002 to 2006, Nigro was sentenced to life in prison in 2011 for ordering the 2003 murder of Adolfo Bruno. Nigro died on April 24, 2019, at the age of 74[222]

- Ciro Perrone – a former capo. In 1998, Perrone was promoted to captain taking over Matthew Ianniello's old crew. In July 2005, Perrone along with Ianniello and other members of his crew were indicted on extortion, loansharking, labor racketeering and illegal gambling.[223] In 2008, Perrone was sentenced to five years for racketeering and loan sharking.[224] Perrone ran his crew from a social club and Don Peppe's restaurant in Ozone Park, Queens.[224] In 2009, Perrone lost his retrial and was sentenced to five years for racketeering and loan sharking.[225] Perrone was released from prison on October 14, 2011.[226] Perrone died in 2011.

- John "Zackie" Savino – born in 1898 in Bari, Southern Italy. He immigrated to the United States in 1912 and settled into Upper Manhattan, Harlem. He later moved to the Bronx area. Savino reportedly served under Genovese capo Jimmy Angelina. He died in the late 1970s or 1980s.

- Frank "Farby" Serpico – born in 1916 in Corona, Queens. Serpico was a member of the 116th Street Crew of the Genovese family. He was promoted to acting boss or street boss by Vincent Gigante from 1998 to 2001 He died in 2002.

- Charles "Chuckie" Tuzzo – capo operating in New Jersey, Brooklyn and Manhattan. In 2002, Tuzzo was indicted with Liborio Bellomo, Ernest Muscarella and others for infiltrating the International Longshoremen's Association (ILA) local in order to extort waterfront companies operating from New York, New Jersey, and Florida.[227][228] On February 2, 2006, Tuzzo was released from prison after serving several years on racketeering and conspiracy charges.[229] On October 21, 2014, Tuzzo along with soldier Vito Alberti were indicted in New Jersey on loansharking, gambling and money laundering charges.[230] Tuzzo died in July 2020.

- Eugene "Charles" Ubriaco – was a member of the Morello family, who lived on East 114th Street.[6] Ubriaco was arrested in June 1915 for carrying a revolver and was released on bail. On September 7, 1916, Ubriaco along with Nicholas Morello meet with the Navy Street gang in Brooklyn and they both were shot to death on Johson Street in Brooklyn.[6][231]

- Joseph Zito – soldier in the Manhattan faction (the West Side Crew) under capo Rosario Gangi. Zito was involved in bookmaking and loansharking business.[232] Law enforcement labeled Zito as acting underboss from 1997 through 2003, but he was probably just a top lieutenant under official underboss Venero Mangano. In the mid-1990s, Zito frequently visited Mangano in prison after his conviction in the Windows Case. Zito relayed messages from Mangano to the rest of the family leadership. On April 7, 2020 Joseph Zito died at the age of 83.[233]

Government informants and witnesses[]

- Joseph "Joe Cargo" Valachi – he exposed the inner workings of the American Mafia in 1963. Valachi was active since the Castellammarese War during the early 1930s, as an associate of the Lucchese crime family; however; after the murder of Salvatore Maranzano in 1931, he joined the Genovese family. Valachi was a soldier in the crew of Anthony Strollo. In 1959, Valachi was sentenced to 15 years' imprisonment for narcotics involvement. He feared that crime family boss and namesake, Vito Genovese, ordered a murder-contract on him in 1962. Valachi and Genovese were both serving prison sentences for heroin trafficking. On June 22, 1962, he murdered another prisoner in the yard, whom he mistook for Joseph DiPalermo, a Mafia member he believed was tasked to kill him. Facing the death penalty, Valachi testified before the United States Senate Committee in 1963. He died in 1971 of a heart attack while imprisoned at FCI La Tuna.

- Giovanni "Johnny Futto" Biello – born in 1906. He was a former capo who was active in the Miami area. He ran the Peppermint Lounge during the 1960s for Matthew Ianniello. Biello was a very good friend to Joseph Bonanno, the namesake and former Bonanno crime family leader. He claimed he was close friends with John Roselli, a high-ranking member of the Chicago Outfit.[234] Biello, along with Joseph Colombo, was supposed to participate in Bonanno's 1962 plot to murder New York crime family bosses, Tommy Lucchese and Carlo Gambino; however, the plan was revealed to the Mafia Commission. Colombo was awarded with his own crime family, the Profaci family—now the Colombo crime family; however, Biello was later murdered. He was shot to death on 17 March 1967, by future Genovese capo George Barone, who would later confess to the murder and become an informant in 2001. His murder was either ordered by Joseph Bonanno or Anthony Salerno and Matthew Ianniello. Before his murder, he allegedly transferred to the Patriarca crime family. In 2012, his son-in-law released a book about Biello's life, named the Peppermint Twist.[235][236]

- Vincent "Fish" Cafaro – former capo and close associate of Tony Salerno. Cafaro was a heroin dealer before joining the Genovese family. He was a protegee of Genovese high-ranking member Anthony Salerno.[237] Cafaro was inducted into the Genovese crime family in 1974. He was assigned to Salerno's crew and operated out of East Harlem. For over a decade, Cafaro had influence within the N.Y.C. District Council of Carpenters. Along with Genovese and Gambino members, he received kickback payments. After fellow conspirator and Genovese capo Vincent DiNapoli was sentenced to prison, Cafaro became even more powerful and wealthy; however, he was eventually forced to give DiNapoli some custom within the Carpenter Council. After his 1986 indictment, he wore a wire for five months for the FBI.[238] In 1990, he testified against Gambino boss John Gotti, who ordered the shooting of a Carpenter Council official in 1986.[239]

- George Barone – former soldier.[240] He was allegedly a founding member of the real-life Jets street gang. In February 1954 while working as a longshoreman recruiter, Barone and a few friends caught and cornered William Torres, who was dissatisfied that he was not hired. Barone repeatedly hit Torres with a metal bar. Police charged him with felonious assault; however, it was later dropped to disorderly conduct. At a meeting with the Gambino crime family in the late 1960s, it was agreed upon that the Gambino family would own the Brooklyn and Staten Island waterfronts, and the Genovese family would control the Manhattan and New Jersey waterfronts.[241] By the early 1970s, Barone was the official Genovese representative for the Genovese-owned waterfronts and was a soldier for the family.[242] By the late 1970s, he controlled the Florida waterfront. In 1979, he was sentenced to 15 years in prison for racketeering; however, he only served seven years behind bars. Shortly after his 2001 indictment for extortion and racketeering, Barone decided to cooperate in April 2001 after being "put on the shelf" by the Genovese hierarchy. He testified against Gambino captain Anthony Ciccone in 2003. He had participated in nearly 20 murders. In 2009, he testified against Genovese capo Mikey Coppola.[243][244] Barone died in December 2010 at the age of 86.

- Louis Moscatiello Sr. – former acting capo and soldier active in the Bronx.[245][246] He was in charge of the Genovese infiltration of the drywall and construction industry. In 1991, he was convicted of bribing a labor official. He took a plea deal in 2004 and cooperated with the government. He was set to testify against Joseph Olivieri, a Genovese family soldier;[247] however, he died in February 2009.

- John "JB" Bologna – former associate.[248] He began cooperating in 1996 as a tipster for the FBI. He was primarily active in the Springfield, Massachusetts area and served as an associate to Genovese capo Adolfo Bruno. Bologna was sentenced to eight years in prison; some of his charges included murder conspiracy, illegal gambling, extortion and racketeering. He died in prison on 17 January 2017.

- Michael "Cookie" D’Urso – former associate involved in loansharking, fraud, loansharking and murder. He wore a Rolex with a recording wire from 1998 to 2001 after he was arrested for driving the getaway car and supplying the gun in the 1996 murder of John Borelli. By 2007, his testimony has led to over 70 convictions. In March 2007, he was sentenced to 5 years probation and a $200 fine for the murder. D’Urso reportedly informed on the Genovese family after he was shot in the head over a gambling debt and his cousin Tino Lombardi was shot dead.

- Renaldi Ruggiero – former captain who headed the South Florida crew.[249] It is noted that in 2003, he gave the approval to extort $1.5 million from a South Florida businessman, who was held for ransom in the office of Genovese associate, Francis J. O'Donnell, and a gun was held to his head, in October 2003. The South Florida businessman was beaten up and had all of his fingers broken; one of his hands were severely damaged and he was then threatened to pay the money by the following week, implying that he would be murdered if he failed to follow through. It was also noted that Ruggiero was active in loan sharking, and was charging 40 of his customers between 52 and 156 percent interest. He was arrested in 2006 alongside six other Genovese members and associates, including Albert Facchiano who was aged 96 at the time, for several crimes, including extortion, armed robbery and money laundering. He faced 120 years in prison, if convicted. Ruggiero cooperated with the government in February 2007 and broke his Omerta by admitting his involvement with the American Mafia and that he served as a capo for the Genovese family, as part of his plea deal.[250][251] In February 2012, he was sentenced to 14 years' imprisonment; however, prosecutors recommended that Ruggiero should serve half of the sentence because of his cooperation, which the judge accepted.

- Felix Tranghese – former capo and soldier. Tranghese was proposed for membership into the Genovese family in 1982 by Adolfo Bruno. He cooperated with the government in 2010, as a result of being "shelved" in the year of 2006.[252] He admitted to receiving the message of the murder contract on Western Massachusetts capo Adolfo Bruno from high-ranking members of the Genovese family in New York, and to delivering the message to Bruno's crew. He also admitted to carrying out extortion and several shootings on behalf of former Genovese street boss, Arthur Nigro. In 2011 and 2012, he returned to New York to testify in 2 separate murder trials, alongside Anthony Arillotta.

- Anthony "Bingy" Arillotta – former soldier who became a government witness in 2010, alongside Felix Tranghese, a fellow Genovese-Springfield crew member. He admitted to his involvement in the 2003 murders of capo Adolfo Bruno and Gary Westerman, his brother-in-law. He also plead guilty to the attempted murder of a New York union boss, which also occurred in 2003. Like Tranghese, he was sentenced to 4 years' imprisonment and both had relocated to Springfield after their release.

- Anthony Zoccolillo – former associate of the Genovese and Bonanno families, Zoccolillo was arrested in 2013 and charged with running an illegal gambling scheme and distributing marijuana and oxycodone.[253] He pleaded guilty and testified against Salvatore "Sally KO" Larca, a member of Ernest Muscarella's crew.[254]

In popular culture[]

The Genovese crime family has a long history of portrayal in Hollywood as the subject of film and television.

Television[]

- Godfather of Harlem (2019)

Film[]

- Mobsters (1991)[255]

References[]

- ^ "The Changing Face of organize crime in New Jersey" (PDF). State of New Jersey Commission of Investigation. May 2004.

- ^ a b The Frank And Fritzy Show: Cast Archived 2008-03-14 at the Wayback Machine - the wiretap network - wmob.com

- ^ a b c Marzulli, John (July 1, 2009). "Mobster 'Mikey Cigars' Coppola won't rat out pals in Genovese crew". New York Daily News. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ Jerry Capeci The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Mafia, 2nd Edition pg.59

- ^ a b Capeci, Jerry. The complete idiot's guide to the Mafia "The Mafia's Commission" (pp. 31–46)

- ^ a b c 2 Die In Pistol Fight in Brooklyn Street, The New York Times, September 8, 1916

- ^ David Critchley The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891–1931 pg.155

- ^ Epic saga of the Genovese Crime Family Archived 2005-03-10 at the Wayback Machine(Page 1)By Anthony Bruno - Crime Library on truTV.com

- ^ a b c d e f g h The Five Families. MacMillan. 13 May 2014. ISBN 9781429907989. Retrieved June 22, 2008.

- ^ Reppetto, Thomas (2004). American Mafia: a history of its rise to power (1st ed.). New York: Henry Holt and Company. p. 137. ISBN 0-8050-7210-1.

Joe Adonis.

- ^ Pollak, Michael (June 29, 2012). "Coney Island's Big Hit". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ^ Sifakis, (2005). pp. 87–88

- ^ Gosch, Martin A.; Hammer, Richard; Luciano, Lucky (1975). The Last Testament of Lucky Luciano. Little, Brown. pp. 130–132. ISBN 978-0-316-32140-2.

- ^ Sifakis

- ^ Cohen, Rich (1999). Tough Jews (1st Vintage Books ed.). New York: Vintage Books. pp. 65–66. ISBN 0-375-70547-3.

Genovese maranzano.

- ^ "Lucky Luciano: Criminal Mastermind," Time, Dec. 7, 1998

- ^ "Genovese family saga". Crime Library.

- ^ "The Genovese Family," Crime Library, Crime Library Archived December 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Commission's Origins". The New York Times. 1986. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ^ Gribben, Mark. "Murder, Inc.: Dutch gets his". Crime Library. Archived from the original on 9 October 2008. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ Gosch, Martin & Richard Hammer (2013). The Last Testament of Lucky Luciano: The Mafia Story in His Own Words. Enigma Books. pp. 223–224. ISBN 9781936274581.

- ^ Newark, p. 81

- ^ "Schultz is shot, one aide killed, and 3 wounded" (PDF). The New York Times. October 24, 1935. Retrieved 2 September 2013.(subscription required)

- ^ "Schultz's Murder Laid to Lepke Aide" (PDF). The New York Times. March 28, 1941. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- ^ Stolberg, p. 133

- ^ a b Raab, Selwyn (2005). Five Families. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 135–136.

- ^ a b "How prosecutors brought down Lucky Luciano," American Bar Association Journal, [https://www.abajournal.com/magazine/article/how_prosecutors_brought_down_lucky_luciano

- ^ "Lucania Convicted with 8 in Vice Ring on 62 Counts Each" (PDF). The New York Times. June 8, 1936. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

- ^ "Luciano Trial Website". Archived from the original on January 31, 2009.

- ^ "Lucania Sentenced to 30 to 50 Years; Court Warns Ring" (PDF). The New York Times. June 19, 1936. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

- ^ Sifakis, Carl (2005). The Mafia encyclopedia (3. ed.). New York: Facts on File. p. 277. ISBN 0-8160-5694-3.

- ^ "Pardoned Luciano on His Way to Italy" (PDF). The New York Times. February 11, 1946. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Frank Costello Dies of Coronary at 82; Underworld Leader" (PDF). New York Times. February 19, 1973. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ^ Kandell, Jonathan (July 28, 2004). "Carmine De Sapio, Political Kingmaker and Last Tammany Hall Boss, Dies at 95". The New York Times. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- ^ "Costello Is Released in $50,000 Bail". nytimes.com. June 20, 1954.

- ^ Epic saga of the Genovese Crime Family Archived 2007-12-17 at the Wayback Machine(Page 3) - By Anthony Bruno - Crime Library on truTV.com

- ^ "Costello is Shot Entering Home; Gunman Escapes Wound" (PDF). New York Times. May 3, 1957. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ^ Epic saga of the Genovese Crime Family Archived 2007-12-17 at the Wayback Machine(Page 4) - By Anthony Bruno - Crime Library on truTV.com

- ^ "20 Apalachin Convictions Ruled Invalid On Appeal". Toledo Blade. November 29, 1960. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ a b United States of America, Appellee v. Russell Bufalino et..

- ^ Tully, Andrew (September 2, 1958). "Mafia Raid Confirms 20-year Undercover Findings by T-Men". The Pittsburgh Press. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ Feinberg, Alexander (April 18, 1959). "Genovese is Given 15 Years in Prison in Narcotics Case" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- ^ Epic saga of the Genovese Crime Family Archived 2007-12-20 at the Wayback Machine(Page 5) - By Anthony Bruno - Crime Library on truTV.com

- ^ a b c "History of La Cosa Nostra". fbi.gov.

- ^ Jerry Capeci. (2002) "The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Mafia", Alpha Books. p. 200. ISBN 0-02-864225-2

- ^ Rudolf, Robert (1993). Mafia Wiseguys: The Mob That Took on the Feds. New York: SPI Books. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-56171-195-6.

- ^ Dietche, Scott M. (2009). The Everything Mafia Book: True-life accounts of legendary figures, infamous crime families, and nefarious deeds. Avon, Massachusetts: Adams Media. pp. 188–189. ISBN 978-1-59869-779-7.

- ^ Kelly, G. Milton (October 1, 1963). "Valachi To Tell Of Gang War For Power". Warsaw Times-Union. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "The rat who started it all; For 40 years, Joe Valachi has been in a Lewiston cemetery, a quiet end for the mobster who blew the lid off Cosa Nostra when he testified before Congress in 1963". buffalonews.com. October 9, 2011.

- ^ Bernstein, Adam (June 14, 2006). "Lawyer William G. Hundley, 80". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 21, 2015.