Georg Friedrich Grotefend

Georg Friedrich Grotefend (9 June 1775 – 15 December 1853) was a German epigraphist and philologist. He is known mostly for his contributions toward the decipherment of cuneiform.

Georg Friedrich Grotefend had a son, named Carl Ludwig Grotefend, who played a key role in the decipherment of the Indian Kharoshthi script on the coinage of the Indo-Greek kings, around the same time as James Prinsep, publishing Die unbekannte Schrift der Baktrischen Münzen ("The unknown script of the Bactrian coins") in 1836.[1]

Life[]

He was born at Hann. Münden and died in Hanover. He was educated partly in his native town, partly at Ilfeld, where he remained till 1795, when he entered the University of Göttingen, and there became the friend of Heyne, Tychsen and Heeren. Heyne's recommendation procured for him an assistant mastership in the Göttingen gymnasium in 1797. While there he published his work De pasigraphia sive scriptura universali (1799), which led to his appointment in 1803 as of the gymnasium of Frankfurt, and shortly afterwards as conrector. In 1821 he became director of the gymnasium at Hanover, a post which he retained till his retirement in 1849. One year before retiring he received a medal commemorating his 50th anniversary of working at the gymnasium at Hanover. This medal made by the local engraver Heinrich Friedrich Brehmer links Grotefends jubilee with the 500th anniversary of the school he taught at. Both occasions were celebrated on 2nd of February 1848.[2]

Work[]

Philology[]

Grotefend was best known during his lifetime as a Latin and Italian philologist, though the attention he paid to his own language is shown by his Anfangsgründe der deutschen Poesie, published in 1815, and his foundation of a society for investigating the German tongue in 1817. In 1823/1824 he published his revised edition of Helfrich Bernhard Wenck's Latin grammar, in two volumes, followed by a smaller grammar for the use of schools in 1826; in 1835–1838 a systematic attempt to explain the fragmentary remains of the Umbrian dialect, entitled Rudimenta linguae Umbricae ex inscriptionibus antiquis enodata (in eight parts); and in 1839 a work of similar character upon Oscan (Rudimenta linguae Oscae). In the same year his son Carl Ludwig Grotefend published a memoir on the coins of Bactria, under the name of Die Münzen der griechischen, parthischen und indoskythischen Könige von Baktrien und den Ländern am Indus.

He soon, however, returned to his favourite subject, and brought out a work in five parts, Zur Geographie und Geschichte von Alt-Italien (1840–1842). Previously, in 1836, he had written a preface to Friedrich Wagenfeld's translation of the Sanchoniathon of Philo of Byblos, which was alleged to have been discovered in the preceding year in the Portuguese convent of Santa Maria de Merinhão.

Old Persian cuneiform[]

But it was in the East rather than in the West that Grotefend did his greatest work. The Old Persian cuneiform inscriptions of Persia had for some time been attracting attention in Europe; exact copies of them had been published by Jean Chardin in 1711,[3] the Dutch artist Cornelis de Bruijn and the German traveller Niebuhr, who lost his eyesight over the work; and Grotefend's friend, Tychsen of Rostock, believed that he had ascertained the characters in the column, now known to be Persian, to be alphabetic.

At this point Grotefend took the matter up. Having a taste for puzzles, he made a bet with drinking friends around 1800 that he could decipher at least part of the Persepolis inscriptions.[4][5] His first discovery was communicated to the Royal Society of Göttingen in 1802,[6] but his findings were dismissed by these academics.[7] His work was denied official publication, but Tychsen published a review of Grotefend's work in the literary gazette of Göttingen in September 1802, which presented the argument made by Grotenfend.[8] In 1815, Grotefend was only able to give an account of his theories in the work of his friend Heeren on ancient history.[7][6][9] His article appeared as an appendix in Heeren's book on historical research and was entitled "On the Interpretation of the Arrow-headed Characters, particularly of the Inscriptions at Persepolis".[10]

Decipherment method[]

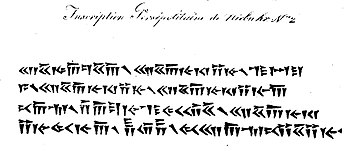

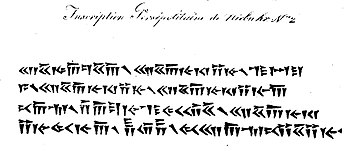

Grotefend had focused on two inscriptions from Persepolis, called the "Niebuhr inscriptions", which seemed to have broadly similar content except for the name of the rulers.[11]

Niebuhr inscription 1. Now known to mean "Darius the Great King, King of Kings, King of countries, son of Hystaspes, an Achaemenian, who built this Palace".[11]

Niebuhr inscription 2: Now known to mean "Xerxes the Great King, King of Kings, son of Darius the King, an Achaemenian".[11]

In 1802, Friedrich Münter had realized that recurring groups of characters must be the word for “king” (