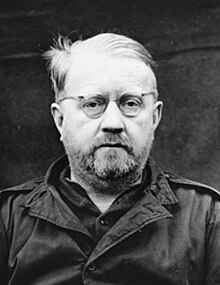

Gerhard Rose

Gerhard August Heinrich Rose (November 30, 1896 in Danzig – January 13, 1992 in Obernkirchen) was a German expert on tropical medicine. Participating in Nazi human experimentation at Dachau and Buchenwald, he infected Jews, Romani people, and the mentally ill with malaria and typhus. Sentenced to life in prison, he was released in 1953.

Early life[]

Rose was born in Danzig (then part of West Prussia, Prussia, Germany, now Gdańsk Poland). Rose attended high schools in Stettin, Düsseldorf, Bremen and Breslau. After graduation, he started to study medicine at the Kaiser Wilhelm Academy for military medical education in Berlin. In 1914, he was active in the Pépinière Corps Saxonia.[1] He moved to the Friedrich-Wilhelms-University Berlin and to the Silesian Friedrich-Wilhelm University of Breslau.[2] Rose insisted the medical state examination on 15 November 1921 with the mark "very good", received his doctorate on November 20, 1922 with the grade "Magna cum laude" and received the approbation as a doctor on 16 May 1922. Rose's training was therefore interrupted from 1914 to 1918 by participating in the First World War. In 1923 he became a member of the Corps Franconia Hamburg.[1] In the period 1922-1926 Rose was as a medical assistant at the Robert Koch Institute in Berlin, at the Hygienic Institute in Basel and at the Anatomical Institute of the University of Freiburg.

China[]

1929 Rose left Germany for work in China. He was a medical adviser for the Kuomintang-government. In December 1929 he was appointed director of the medical office in Chekiang, furthermore he was advisor for health at the ministry of the interior in Chekiang. His time in China was interrupted from studies in Europe, Asia and Africa. On 1 November 1930 Rose joined the Nazi Party (Member number: 346.161).[3]

Return from China[]

Prior to the Second Sino-Japanese War Rose returned in September 1936 and took over on 1 October, the head of the Department of Tropical Medicine at the Berlin Robert Koch Institute. From summer semester 1938 Rose held at Berlin University lectures and exercises to tropical hygiene and tropical medicine. On February 1, 1943 Rose was named vice president of the Robert Koch Institute.

1939 Rose entered the service of the medical service of the Luftwaffe. In 1942, he was appointed advisory hygienists and tropical medicine at the medical service of the Luftwaffe. When the war ended, Rose held the rank of a General physician.

Malaria-experiments[]

Rose's proceeder as Head of Department at Robert-Koch-Institut was Claus Schilling. Rose continued the Malaria-experiments of Schilling, mostly with psychiatry patients.[4] Austrian psychiatrist Julius Wagner-Jauregg succeeded in 1917, to gain success with malaria against General paresis of the insane. This malaria therapy was also used by Rose for Schizophrenia. The experiments were made in the concentrations camps in Dachau and Buchenwald and with mentally ill Russian prisoners in a psychiatric clinic in Thuringia.[5]

Between 1941 and 1942 Rose tested for IG Farben industry, (Leverkusen), new antimalarials.[6] Malaria experiments with the participation of Rose are documented for the Saxon country-sanatorium Arnsdorf. By July 1942 altogether 110 patients were infected by mosquito bites.[7] In a first test series with 49 people, four people died. The experiments in Arnsdorf fell in the time of Nazi medical murders, the Aktion T4. Subjects were transferred to other institutions and killed there. According to the company [7] Rose sought out one of the main organizers of the action T4, Viktor Brack, and received a promise that his subjects were to be excluded from the transfers.

Rose stood still in conjunction with his predecessor Claus Schilling. From January 1942 human experiments were conducted in Dachau concentration camp to develop a vaccine against malaria [8]

Typhus vaccine trials in concentration camps[]

The ghetto isolation of the Jews and the states in the POW camp led in the German-occupied territories in the East to the outbreak of typhus epidemics.[9] As the main disseminator of typhus in the General Government were blamed "originating from the Jewish quarter of Warsaw vagabond Jews". met with Rose in Warsaw [10] By Wehrmacht tourists and deported to the German Reich, the disease spread in the autumn of 1941, also in the Reich. In December 1941, on the search for a suitable vaccine several meetings between representatives of the Armed Forces, of manufacturers and representatives of the authorities responsible for health issues Reich Interior Ministry were held. Since the vaccines from several manufacturers were new and templates any experiences about their protection, human experiments in Buchenwald were agreed. The experiments were under control of Joachim Mrugowsky from the Hygiene Institute of the Waffen SS. In Buchenwald Erwin Ding-Schuler was the experimenter.

On March 17, 1942, Rose attended together with Eugen Gildemeister the experimental station at Buchenwald. At this time, 150 prisoners had been infected with typhus, with 148 of them the disease was found.[11]

At the 3rd session of the Consultative Medical Wehrmacht Ding-Schuler held in May 1943 a lecture entitled On the results of the examination of different spotted fever vaccines against the classical typhus , in which he - the attempts camouflaging - whose results lectured [12] Rose, participant in the meeting and advised of the nature of the human experiments, brought before the meeting objected to the nature of the human trials. According to later information of those who were present, it was whispered quietly [...]among the participants of the meeting "that this could have been concentration camp experiments." [13] The opposition of Rose was later confirmed independent from the conference participants by Eugen Kogon. Kogon was an inmate of Ding-Schuler, who repeatedly made known his displeasure with the intervention of Rose in Buchenwald.[14]

Despite his protests in May 1943, Rose turned on 2 December 1943, to Joachim Mrugowsky from the Hygiene Institute of the Waffen SS with the request, to perform in the Buchenwald concentration camp further series of tests with a new typhus vaccine.[15] Enno Lolling, head of Office D III (sanitation and camp Hygiene) in SS Economic and administrative main Office, approved on February 14, 1944, the series of experiments, "suitable 30 gypsies" should be transferred to Buchenwald. The tests were made between March and June 1944. Six of the 26 infected prisoners died.[16]

Haagen complained on October 4, 1943 in writing to Rose that the appropriate prisoners were missing to carry out infection experiments on vaccinated persons.[17] On 13 November 1943, the SS office sent 100 prisoners to Haagen. In early 1944, the Institute of Hygiene of the Luftwaffe led by Rose was settled into the sanatory Pfafferode near Mulhouse (Thuringia).[18] In the institution Pfafferode, led by Theodor Steinmeyer, were at that time patients in the second phase of the Nazi medical murders of action Brandt murdered by food deprivation and the overdose of drugs.

Defendant in the Doctors Trial[]

When the war ended on May 8, 1945, Rose was captured by Allied troops. Evidence suggesting the involvement of doctors from the Luftwaffe to the human experiments in concentration camps resulted from the Nuremberg Trials of the main war criminals.[19] Accused was also Hermann Göring. According to the medical historian Udo Benzenhöfer allied investigations about the people involved led to the higher-ranked and highest-ranking defendants."[19] before. Rose was just one of seven other accused doctors of the Luftwaffee in the physician process. Central to the case against Rose were typhus experiments in the concentration camps Buchenwald and Natzweiler.[19] During the process, Rose was also accused of having supported the malaria experiments of Claus Schilling in Dachau. Of the other defendants differed Rose by his intellectual nature and his extensive medical experience.[20] Based on his international experience he drew in his testimony between 18 and 25 April 1947 numerous comparisons between the tests in the German concentration camps and experiments that foreign researchers had carried out on humans.[21] He had assumed that the experiments in the Buchenwald concentration camp "should be carried out to criminals sentenced to death."[22] This was contradicted by the charged as a witness in Nuremberg former inmate Eugen Kogon (1903-1987): After one or two trials it became impossible to find volunteers in Buchenwald. He was not a single case in which a death sentence was passed.[23] During the interrogation the prosecution put forward as evidence Roses letter to Joachim Mrugowsky of 2 December 1943. Rose then compared himself to a lawyer, who was opponent of the death penalty and insets in the art and to the Government for their elimination: "If he does not succeed, it will remain as still in the profession and in its surroundings there, and he can even be may be forced to utter such a death sentence even though he basically is an opponent of this institution."[24]

Prison and campaign to free[]

On 31 January 1951, the penalty was reduced to fifteen years in prison by the American High Commissioner John J. McCloy. The pressure was his bitterness strengthened against his former superiors. “[25] On 3 June 1953 Rose was the last of the in the doctors' trial to imprisonment condemned physicians to be dismissed from Landsberg prison.

Rose's detention was accompanied by various efforts to his early release by Rose's wife and Ernst Georg Nauck, Director of Hamburger Bernhard Nocht Institute.[26] on September 29, 1950 the Free Association of German Hygienists and microbiologists contacted John J. McCloy with a request for Roses release: His large professional experience and previous performance to be expected, "that he will give the science and humanity many valuable benefits when used as a last, after more five and a half year prison his profession and his work is returned "[27] In the weekly Hamburg newspaper Die Zeit an article was published with the heading Zu Unrecht in Landsberg. Ein Wort für den Forscher und Arzt Gerhard Rose. (Wrongly in Landsberg. A word for the doctor and researcher Gerhard Rose).The article was written by .[28]

A clemency petition of 2 November 1953 launched Rose in addition to his arguments in the Doctors' Trial order. The actually responsible for the typhus experiments have not been held accountable and are partly now being transferred to the US government service.[29]

Disciplinary proceedings[]

After being released, Rose carried on his rehabilitation.[29] As a so-called "131er" could also officials who had worked for the National Socialist state, are admitted within the Federal Republic of Germany as civil servants. Because of a Malfeasance in office disciplinary proceedings were initiated in May 1956 against Rose. on October 24, 1960 acquitted him the Federal Disciplinary Body VII in Hamburg for free.[30] A witness at the court was Rudolf Wohlrab who had undertaken human experiments with typhus in 1940, in Warsaw. He was in contact at this time with Rose and Ernst Georg Nauck.[31] The findings of the court led to criticism by Alexander Mitscherlich. Mitscherlich was heard on 21 October 1960 as a witness because he had issued the document collection Science without humanity about the physician process. According to Mitscherlich, the relevant documents were not in the court files.

Literature[]

- Ebbinghaus, Angelika (Hrsg.): Vernichten und Heilen. Der Nürnberger Ärzteprozeß und seine Folgen. Aufbau-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-7466-8095-6.

- Dörner, Klaus (Hrsg.): Der Nürnberger Ärzteprozeß 1946/47. Wortprotokolle, Anklage- und Verteidigungsmaterial, Quellen zum Umfeld. Saur, München 2000, ISBN 3-598-32028-0 (Erschließungsband) ISBN 3-598-32020-5 (Mikrofiches).

- Ulrich Dieter Oppitz (Bearb.): Medizinverbrechen vor Gericht. Die Urteile im Nürnberger Ärzteprozeß gegen Karl Brandt und andere sowie aus dem Prozess gegen Generalfeldmarschall Milch. Palm und Enke, Erlangen 1999, ISBN 3-7896-0595-6.

- Mitscherlich, Alexander (Hrsg.): Medizin ohne Menschlichkeit. Dokumente des Nürnberger Ärzteprozesses. 16. Auflage, Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-596-22003-3.

- Wolters, Christine: Humanexperimente und Hohlglasbehälter aus Überzeugung. Gerhard Rose – Vizepräsident des Robert-Koch-Instituts. In: Frank Werner (Hrsg.): Schaumburger Nationalsozialisten. Täter, Komplizen, Profiteure. Verlag für Regionalgeschichte, Bielefeld 2009, ISBN 978-3-89534-737-5, p. 407–444.

See also[]

- Nazi human experimentation

- Doctors' Trial

- Kurt Blome

- Unit 731

- Yellow fever

- Erich Traub

- Claus Schilling

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b 1960, 63, 189; 60, 545; 40, 1096

- ^ biographische Angaben zu Rose bei: Dörner, Ärzteprozeß, S. 136 (Erschließungsband), S. 8/03112ff. (Gnadengesuch vom 2. November 1953) S. 8/03174ff. (Urteil der Bundesdisziplinarkammer VII vom 24. Oktober 1960 (Az. VII VI 8/60)). Ernst Klee: Auschwitz, die NS-Medizin und ihre Opfer. 3. Auflage, S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1997, ISBN 3-10-039306-6, S. 126.

- ^ Dörner, Ärzteprozess; S. 136.

- ^ Klee, Auschwitz, S. 116 f., 126 f.

- ^ Eckart, WU; Vondra, H (2000). "Malaria and World War II: German malaria experiments 1939-45". Parassitologia. 42 (1–2): 53–8. PMID 11234332.

- ^ Dörner, Ärzteprozess, S. 136.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Zu Arnsdorf und den genannten Zahlen siehe Klee, Auschwitz, S. 127 ff.

- ^ beispielhaft: Schreiben von Claus Schilling an Gerhard Rose vom 4. April 1942 beim Nuremberg Trials Project Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine (Nürnberger Dokument NO-1752). Schreiben von Gerhard Rose an Claus Schilling vom 27. Juli 1943 beim Nuremberg Trials Project Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine (Nürnberger Dokument NO-1755)

- ^ Klee, Auschwitz, S. 287 f.

- ^ Rudolf Wohlrab: Flecktyphusbekämpfung im Generalgouvernement. Münchner Medizinische Wochenzeitschrift, 29. Mai 1942 (Nr. 22) S. 483 ff. Zitiert nach: Klee, Auschwitz, S. 287.

- ^ Klee, Auschwitz, S. 292. Der Eintrag im Tagebuch der Versuchsstation beim Nuremberg Trials Project Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine (Nürnberger Dokument NO-265, S. 3)

- ^ Mitscherlich, Medizin, S. 126; Klee, Auschwitz, S. 310 f.

- ^ Eidesstattliche Erklärung Walter Schells vom 1. März 1947, zitiert nach: Mitscherlich, Medizin, S. 126. Die Erklärung Schells in englischer Übersetzung beim Nuremberg Trials Project Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Klee, Auschwitz, S. 311

- ^ Mitscherlich, Medizin, S. 129. Siehe auch Nürnberger Dokument NO-1186.

- ^ Mitscherlich, Medizin, S. 130 f. bezugnehmend auf das Buchenwalder Tagebuch, S. 23 (Nürnberger Dokument NO-265)

- ^ Schreiben Eugen Hagen an Gerhard Rose vom 4. Oktober 1943 (Nürnberger Dokument NO-2874), siehe Mitscherlich, Medizin, S. 158 f.

- ^ Klee, Auschwitz, S. 130ff.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Udo Benzenhöfer: Nürnberger Ärzteprozeß: Die Auswahl der Angeklagten. Deutsches Ärzteblatt 1996; 93: A-2929–2931 (Heft 45) (pdf-Datei, 258KB)

- ^ Diese Einschätzung bei Ulf Schmidt: Justice at Nuremberg. Leo Alexander and the Nazi Doctors' Trial. palgrave macmillan, Houndmills 2004, ISBN 0-333-92147-X, S. 226

- ^ Auszüge aus Roses Aussagen bei: Mitscherlich, Medizin, S. 120-124, 131-132, 134-147. Siehe auch Schmidt, Justice, S. 226 ff.

- ^ Verhandlungsprotokoll, S. 6231 ff., zitiert nach Mitscherlich, Medizin, S. 120.

- ^ Verhandlungsprotokoll, S. 1197, zitiert nach Mitscherlich, Medizin, S. 153.

- ^ Verhandlungsprotokoll, S. 6568, zitiert nach Mitscherlich, Medizin, S. 132.

- ^ Formular „Führung in der Anstalt“, 9. November 1953, in: Dörner, Ärzteprozess, S. 8/03125 f.

- ^ siehe Dörner, Ärzteprozess, S. 8/03094 ff. Ernst Georg Nauck hatte zuvor vier Erklärungen an Eides statt für Roses Verteidigung beigesteuert. Die Erklärung in englischer Übersetzung beim Nuremberg Trials Project Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine. Zu den Bemühungen um Roses Freilassung siehe auch: Angelika Ebbinghaus: Blicke auf den Nürnberger Ärzteprozeß. In: Dörner, Ärzteprozeß, (Erschließungsband), S. 66.

- ^ Petition anlässlich der Tagung der Freien Vereinigung deutscher Hygieniker und Mikrobiologen in Hamburg am 29. September 1950. In: Dörner, Ärzteprozeß, S. 8/03104.

- ^ Die Zeit, 18. März 1954.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ebbinghaus, Blicke, S. 66.

- ^ Urteil der Bundesdisziplinarkammer VII vom 24. Oktober 1960 (Az. VII VI 8/60). In: Dörner, Ärzteprozeß, S. 8/03173-8/03205.

- ^ Urteil der Bundesdisziplinarkammer VII vom 24. Oktober 1960 (Az. VII VI 8/60). In: Dörner, Ärzteprozeß, S. 8/03199. Zu Wohlrab siehe Ernst Klee: Das Personenlexikon zum Dritten Reich. Wer war was vor und nach 1945. Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 3-596-16048-0, S. 684 und Mitscherlich, Medizin, S. 146. Zu Nauck siehe Klee, Personenlexikon, S. 428, und Klee, Auschwitz, S. 311.

External links[]

- Hedy Epstein. "Gerhard Rose".

- "Gerhard Rose". Nuremberg Trials Project. Harvard Law School Library. Archived from the original on 2006-09-02.

- 1896 births

- 1992 deaths

- Physicians from Gdańsk

- Buchenwald concentration camp personnel

- Dachau concentration camp personnel

- Physicians in the Nazi Party

- Nazi human subject research

- People from West Prussia

- University of Breslau alumni

- Humboldt University of Berlin alumni

- People convicted by the United States Nuremberg Military Tribunals

- German people convicted of crimes against humanity

- German prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment

- Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by the United States military

- Condor Legion personnel

- Recipients of the Knights Cross of the War Merit Cross

- 20th-century Freikorps personnel

- Luftwaffe personnel convicted of war crimes