Go Down Moses

| "Go Down, Moses" | |

|---|---|

| Fisk Jubilee Singers (earliest attested) | |

| Song | |

| Genre | Negro spiritual |

| Songwriter(s) | Unknown |

"Go Down Moses" is a spiritual phrase that describes events in the Old Testament of the Bible, specifically Exodus 5:1:[1] "And the LORD spake unto Moses, Go unto Pharaoh, and say unto him, Thus saith the LORD, Let my people go, that they may serve me", in which God commands Moses to demand the release of the Israelites from bondage in Egypt. This phrase is the title of the one of the most well known African American spirituals of all time. The song discusses themes of freedom, a very common occurrence in spirituals.[2] In fact, the song actually had multiple messages, discussing not only the metaphorical freedom of Moses but also the physical freedom of runaway slaves,[3] and many slave holders outlawed this song because of those very messages.[4] The opening verse as published by the Jubilee Singers in 1872:

When Israel was in Egypt's land

Let my people go

Oppress'd so hard they could not stand

Let my people go

Refrain:

Go down, Moses

Way down in Egypt's land

Tell old Pharaoh

Let my people go

The lyrics of the song represent liberation of the ancient Jewish people from Egyptian slavery, a story recounted in the Old Testament. For enslaved African Americans, the story was very powerful because they could relate to the experiences of Moses and the Israelites who were enslaved by the pharaoh, representing the slave holders,[5] and it holds the hopeful message that God will help those who are persecuted. The song also makes references to the Jordan River, which was often referred to in spirituals to describe finally reaching freedom because such an act of running away often involved crossing one or more rivers.[6][7] Going "down" to Egypt is derived from the Bible; the Old Testament recognizes the Nile Valley as lower than Jerusalem and the Promised Land; thus, going to Egypt means going "down"[8] while going away from Egypt is "up".[9] In the context of American slavery, this ancient sense of "down" converged with the concept of "down the river" (the Mississippi), where slaves' conditions were notoriously worse, a situation which led to the idiom "sell [someone] down the river" in present-day English.[10]

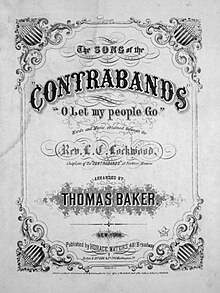

"Oh! Let My People Go"[]

| "Oh! Let My People Go" | |

|---|---|

Sheet music cover, 1862 | |

| Song | |

| Published | 1862 |

| Genre | Negro spiritual |

| Songwriter(s) | Unknown |

Although usually thought of as a spiritual, the earliest written record of the song was as a rallying anthem for the Contrabands at Fort Monroe sometime before July 1862. White people who reported on the song presumed it was composed by them.[11] This became the first ever spiritual to be recorded in sheet music that is known of, by Reverend Lewis Lockwood. While visiting Fortress Monroe in 1861, he heard runaway slaves singing this song, transcribed what he heard, and then eventually published it in the National Anti-Slavery Standard.[12] Sheet music was soon after published, titled "Oh! Let My People Go: The Song of the Contrabands", and arranged by Horace Waters. L.C. Lockwood, chaplain of the Contrabands, stated in the sheet music that the song was from Virginia, dating from about 1853.[13] However, the song was not included in Slave Songs of the United States, despite it being a very prominent spiritual among slaves. Furthermore, the original version of the song sung by slaves almost definitely sounded very different from what Lockwood transcribed by ear, especially following an arrangement by a person who had never before heard the song how it was originally sung.[14] The opening verse, as recorded by Lockwood, is:

The Lord, by Moses, to Pharaoh said: Oh! let my people go

If not, I'll smite your first-born dead—Oh! let my people go

Oh! go down, Moses

Away down to Egypt's land

And tell King Pharaoh

To let my people go

Sarah Bradford's authorized biography of Harriet Tubman, Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman (1869), quotes Tubman as saying she used "Go Down Moses" as one of two code songs fugitive slaves used to communicate when fleeing Maryland.[15] Tubman began her underground railroad work in 1850 and continued until the beginning of the Civil War, so it's possible Tubman's use of the song predates the origin claimed by Lockwood.[16] Some people even hypothesize that she herself may have written the spiritual.[17] Although others claim Nat Turner, who led one of the most well-known slave revolts in history, either wrote or was the inspiration for the song.[18]

In popular culture[]

This section contains a list of miscellaneous information. (February 2017) |

Films[]

- Al Jolson sings it in Alan Crosland' film Big Boy (1930).

- Used briefly in Kid Millions (1934).

- Jess Lee Brooks sings it in Preston Sturges' film Sullivan's Travels (1941).

- Gregory Miller (played by Sidney Poitier) sang the song in the film Blackboard Jungle (1955).

- A reference is made to the song in the film Ferris Bueller's Day Off (1986), when a bedridden Cameron Frye sings, "When Cameron was in Egypt's land, let my Cameron go".

- Sergei Bodrov Jr. and Oleg Menshikov, who play the two main characters in Sergei Bodrov's film Кавказский пленник (1996; Prisoner of the Mountains) dance to the Louis Armstrong version.

- The teen comedy film Easy A (2010) remixed this song with a fast guitar and beats. The song was originally published as Original Soundtrack and is listed in IMDb.[19]

Literature[]

- William Faulkner titled his novel Go Down, Moses (1942) after the song.

- Djuna Barnes, in her field-changing novel Nightwood, titled a chapter "Go Down, Matthew" as an allusion to the song's title.

- in Margaret Mitchell's novel Gone with the Wind, slaves from the Georgia plantation Tara are in Atlanta, to dig breastworks for the soldiers, and they sing "Go Down, Moses" as they march down a street.

Music[]

- The song was made famous by Paul Robeson whose deep voice was said by Robert O'Meally to have assumed "the might and authority of God."[20]

- On February 7, 1958, the song was recorded in New York City and sung by Louis Armstrong with Sy Oliver's Orchestra.[21]

- It was recorded by Doris Akers and the Sky Pilot Choir.[citation needed][22]

- The song has since become a jazz standard, having been recorded by Grant Green, Fats Waller, Archie Shepp, Hampton Hawes and many others.[23]

- It is one of the five spirituals included in the oratorio A Child of Our Time, first performed in 1944, by the English classical composer Michael Tippett (1905–98).

- It is included in some seders in the United States, and is printed in Meyer Levin's An Israel Haggadah for Passover.[24]

- The song was recorded by Deep River Boys in Oslo on September 26, 1960. It was released on the extended play Negro Spirituals No. 3 (HMV 7EGN 39).

- The song, or a modified version of it, has been used in the Roger Jones musical From Pharaoh to Freedom[when?][citation needed]

- The French singer Claude Nougaro used its melody for his tribute to Louis Armstrong in French, under the name Armstrong (1965).

- "Go Down Moses" has sometimes been called "Let My People Go" and performed by a variety of musical artists, including RebbeSoul

- The song heavily influences "Get Down Moses", by Joe Strummer & the Mescaleros on their album Streetcore (2003).

- The song has been performed by the Russian Interior Ministry (MVD) Choir.[25]

- Jazz singer Tony Vittia released a swing version under the name "Own The Night" (2013).

- The phrase "Go Down Moses" is featured in the chorus of the John Craigie song, "Will Not Fight" (2009).

- The phrase "Go Down Moses" is sung by Pops Staples with the Staple Singers in the song "The Weight" in The Last Waltz film by The Band (1976). The usual lyric is actually "Go down Miss Moses".[26]

- Avant-garde singer-songwriter and composer Diamanda Galás recorded a version for her fifth album, You Must Be Certain of the Devil (1988), the final part of a trilogy about the AIDS epidemic that features songs influenced by American gospel music and biblical themes, and later in Plague Mass (1991) and The Singer (1992).

- Composer Nathaniel Dett used the text and melody of "Go Down Moses" throughout his oratorio, "The Ordering of Moses" (1937). In the first section, Dett sets the melody with added-note harmonies, quartal chords, modal harmonies, and chromaticism (especially French augmented sixth chords). Later in the oratorio, "Go Down Moses" is set as a fugue.

Television[]

- The NBC television comedy The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air twice used the song for comedic effect. In the first instance, Will Smith's character sings the song after he and his cousin Carlton Banks are thrown into prison (Smith sings the first two lines, Banks sullenly provides the refrain, then a prisoner sings the final four lines in an operatic voice.)[27] In the second instance, Banks is preparing for an Easter service and attempts to show off his prowess by singing the last two lines of the chorus; Smith replies with his own version, in which he makes a joke about Carlton's height ("...Let my cousin grow!").[citation needed]

- In Dr. Katz, Professional Therapist is sung by Katz and Ben during the end credits of the episode "Thanksgiving" (Season 5, Episode 18).

- Della Reese sings it in Episode 424, "Elijah", of Touched by an Angel, which Bruce Davison sings "Eliyahu".

- In series 2 episode 3 of Life on Mars, the lawyer sings for his client's release.

Recordings[]

- The Tuskegee Institute Singers recorded the song for Victor in 1914.[28]

- The Kelly Family recorded the song twice: live version is included on their album (1988) and a studio version on (1990). The latter also features on their compilation album (1993).

- The Golden Gate Quartet (Duration: 3:05; recorded in 1957 for their album Spirituals).[29]

- "Go Down Moses" was recorded by the Robert Shaw Chorale on RCA Victor 33 record LM/LSC 2580, copyright 1964, first side, second band, lasting 4 minutes and 22 seconds. Liner notes by noted African-American author Langston Hughes.[30]

See also[]

- Christian child's prayer § Spirituals

- Let My People Go (disambiguation)

References[]

- ^ Bible: Exodus 5:1

- ^ Newman, R. S. (1998). Go Down Moses: A Celebration of the African-American Spiritual. Clarkson N. Potter.

- ^ Darden, R. (2004). People Get Ready! A New History of Black Gospel Music. Bloomsbury.

- ^ Newman, R. S. (1998). Go Down Moses: A Celebration of the African-American Spiritual. Clarkson N. Potter.

- ^ Darden, R. (2004). People Get Ready! A New History of Black Gospel Music. Bloomsbury.

- ^ Cleveland, J. J. (Ed.). (1981). Songs of Zion. Abingdon Press.

- ^ Cornelius, Steven (2004). Music of the Civil War Era. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 118. ISBN 0313320810

- ^ For example, in Genesis 42:2 Jacob commands his sons to "go down to Egypt" to buy grain

- ^ In Exodus 1:10, Pharaoh expresses apprehension that the Hebrews would join Egypt's enemies and "go up [i.e. away] from the land"

- ^ Phrases.org.uk

- ^ "Editor's Table". The Continental Monthly. 2: 112–113. July 1862 – via Cornell University.

We are indebted to Clark's School-Visitor for the following song of the Contrabands, which originated among the latter, and was first sung by them in the hearing of white people at Fortress Monroe, where it was noted down by their chaplain, Rev. L.C. Lockwood.

- ^ Graham, S. (2018). Spirituals and the Birth of a Black Entertainment Industry. University of Illinois Press.

- ^ Lockwood, "Oh! Let My People Go", p. 5: "This Song has been sung for about nine years by the Slaves of Virginia."

- ^ Graham, S. (2018). Spirituals and the Birth of a Black Entertainment Industry. University of Illinois Press.

- ^ Bradford, Sarah (1869). Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman. Dennis Brothers & Co. pp. 26–27. Archived from the original on June 13, 2017 – via University of North Carolina: Documenting the American South.

- ^ "Summary of Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman". docsouth.unc.edu. Retrieved January 25, 2017.

- ^ Darden, R. (2004). People Get Ready! A New History of Black Gospel Music. Bloomsbury.

- ^ Newman, R. S. (1998). Go Down Moses: A Celebration of the African-American Spiritual. Clarkson N. Potter.

- ^ "Easy A – Original Sound Tracks". IMDB.

- ^ Brooks, Daphne (January 1, 2006). Bodies in Dissent: Spectacular Performances of Race and Freedom, 1850–1910. Duke University Press. p. 307. ISBN 0822337223.

- ^ Nollen, Scott Allen (2004). Louis Armstrong: The Life, Music, and Screen Career. McFarland. p. 142. ISBN 9780786418572.

- ^ Muhammad, Siebra. "BLACK MUSIC MOMENT: HISTORY OF "GO DOWN MOSES" ~ THE SONG USUALLY THOUGHT OF AS A SPIRITUAL". jobs.blacknews.com. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- ^ "Go Down Moses". Allmusic.com.

- ^ An Israel Haggadah for Passover. New York: H. N. Abrams. 1970.

- ^ Russian Interior Ministry (MVD) Choir Recording. "Go Down Moses". YouTube.

- ^ "The Weight | Robbie-Robertson.com". robbie-robertson.com. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ^ NBC The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. "Go Down Moses". YouTube.

- ^ Gibbs, Craig Martin (2012). Black Recording Artists, 1877–1926: An Annotated Discography. McFarland. p. 43. ISBN 1476600856.

- ^ "The Golden Gate Quartet – Spirituals". Genius. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- ^ The album itself!

Bibliography[]

- The Continental Monthly. Vol. II (July–December 1862). New York.

- Lockwood, L.C. "Oh! Let My People Go: The Song of the Contrabands". New York: Horace Waters (1862).

External links[]

- Sweet Chariot: The Story of the Spirituals, particularly their section on "Freedom" (Web site maintained by The Spirituals Project at the University of Denver)

- Free scores of Go Down Moses in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- American folk songs

- Gospel songs

- Paul Robeson songs

- African-American spiritual songs

- Cultural depictions of Moses

- Year of song unknown

- Songwriter unknown

- Songs about religious leaders

- Songs about Egypt