Granma (yacht)

Granma is the yacht that was used to transport 82 fighters of the Cuban Revolution from Mexico to Cuba in November 1956 for the purpose of overthrowing the regime of Fulgencio Batista. The 60-foot (18 m) diesel-powered cabin cruiser was built in 1943 by Wheeler Shipbuilding of Brooklyn NY as a light armored target practice boat, US Navy C-1994 and modified postwar to accommodate 12 people. "Granma", in English, is an affectionate term for a grandmother; the yacht is said to have been named for the previous owner's grandmother.[1][2][3]

Role in the Cuban revolution[]

The yacht was purchased on 10 October 1956 for MX$50,000 (US$15,000) from the United States-based Schuylkill Products Company, Inc., by a Mexican citizen—said to be Mexico City gun dealer Antonio "The Friend" del Conde[4]—secretly representing Fidel Castro. The builder, Wheeler Shipbuiding, then of Brooklyn NY, now of Chapel Hill NC, also built Hemingway's Pilar.[5] It is still unknown who removed the light armor and expanded the cabin postwar to convert the navy training boat into a civilian yacht. Castro's 26th of July Movement had attempted to purchase a Catalina flying boat maritime aircraft, or a US naval crash rescue boat for the purpose of crossing the Gulf of Mexico to Cuba, but their efforts had been thwarted by lack of funds. The money to purchase Granma had been raised in the US state of Florida by former President of Cuba Carlos Prío Socarrás[6] and Teresa Casuso Morín.[7]

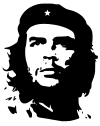

Shortly after midnight on 25 November 1956 in the Mexican port of Tuxpan, Veracruz, Granma was surreptitiously boarded by 82 members of the 26th of July movement including their leader, Fidel Castro, his brother, Raúl Castro, Che Guevara, and Camilo Cienfuegos. The group—who later came to be known collectively as los expedicionarios del yate Granma (the Granma yacht expeditioners)—then set out from Tuxpan at 2 a.m.[8] After a series of vicissitudes and misadventures, including diminishing supplies, sea-sickness, and the near-foundering of their heavily laden and leaking craft, they disembarked on 2 December on the Playa Las Coloradas, municipality of Niquero, in modern Granma Province (after the vessel), formerly part of the larger Oriente Province. Granma was piloted by Norberto Collado Abreu, a World War II Cuban Navy veteran and ally of Castro.[9] The location was chosen to emulate the voyage of national hero José Martí, who had landed in the same region 61 years earlier during the wars of independence from Spanish colonial rule.

Landing[]

We reached solid ground, lost, stumbling along like so many shadows or ghosts marching in response to some obscure psychic impulse. We had been through seven days of constant hunger and sickness during the sea crossing, topped by three still more terrible days on land. Exactly 10 days after our departure from Mexico, during the early morning hours of December 5, following a night-long march interrupted by fainting and frequent rest periods, we reached a spot paradoxically known as Alegría de Pío (Rejoicing of the Pious). –Che Guevara[10]

Batista correctly predicted that the landing would take place, and his troops were ready. Consequentially, the landing party was bombarded by helicopters and airplanes soon after landing. Since the terrain on the coastline provided little cover, the party was an easy target.[11] Many casualties ensued, most of them during battle at further inland. The survivors continued to the foot of Pico Turquino in the Sierra Maestra to carry out guerilla war.[12]

Initially, Batista did not know who exactly were among the casualties, and international media widely reported that Fidel had died.[13] This was, however, not the case. Of the 82, around 20 had survived. According to the most credible version, the survivors were Fidel, Raúl, Guevara, , , Ramiro Valdés, , Efigenio Ameijeiras, , Camilo Cienfuegos, Juan Almeida Bosque, , , , , , , , , and . All others had been either killed, captured, or left behind.[14]

Granma yacht expeditioners[]

The 82 expeditioners were:[15]

After the revolution[]

Soon after the revolutionary forces triumphed on 1 January 1959, the cabin cruiser was transferred to Havana Bay. Norberto Collado Abreu, who had served as main helmsman for the 1956 voyage,[9] received the job of guarding and preserving the yacht.[citation needed]

Since 1976, the yacht has been on permanent display in a glass enclosure at the Granma Memorial adjacent to the Museum of the Revolution in Havana. A portion of old Oriente Province, where the expedition made landfall, was renamed Granma Province in honor of the vessel. UNESCO has declared the Landing of the Granma National Park—established at the location (Playa Las Coloradas)—a World Heritage Site for its natural habitat.[16]

Cuba celebrates 2 December as the "Day of the Cuban Armed Forces",[17] and a replica has also been paraded at state functions to commemorate the original voyage. In further tribute, the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Cuban Communist Party has been called Granma. The name of the vessel became an icon for Cuban communism.[18]

References[]

- ^ Daniel, Frank Jack (November 25, 2006). "Fifty years on, Mexico town recalls young Castro". Archived from the original on November 28, 2006 – via Reuters.

- ^ Arrington, Vanessa (July 2006). "Roots of Cuban Revolution lie in the east". Retrieved January 14, 2007 – via Associated.

- ^ "Time Magazine 1966 report". December 2, 2008. Archived from the original on December 2, 2008. Retrieved December 3, 2006.

- ^ Frank Jack Daniel (November 27, 2006). "Fifty years on, Mexico town recalls young Castro". Caribbean Net News. Archived from the original on November 23, 2007. Retrieved December 2, 2007.

- ^ "History - Wheeler Yacht Company". wheeleryachts.com. Archived from the original on March 23, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- ^ Thomas, Hugh (March 21, 1998). Cuba: The Pursuit of Freedom. pp. 584–585. ISBN 0306808277.

- ^ "HUMANISMO. MEXICO CITY: JANUARY-FEBRUARY 1958, NO. 4". Sotherbys.com. Sotherbys. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- ^ Guevara, Ernesto. Pasajes de la guerra revolucionaria. "Una revolución que comienza" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on June 12, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Cuban Revolutionary Collado Abreu Dies". Associated Press. April 3, 2008. Archived from the original on April 7, 2008. Retrieved April 3, 2008.

- ^ Kellner, Douglas (1989). Ernesto "Che" Guevara. World Leaders Past & Present. Chelsea House Publishers. p. 40. ISBN 1-55546-835-7.

- ^ Cuba Libre 2016, 24:00.

- ^ Cuba Libre 2016, 25:00.

- ^ Cuba Libre 2016, 26:00.

- ^ Bonachea, Ramon L.; Martin, Marta San (2011). Cuban Insurrection 1952-1959. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. p. 107n49. ISBN 978-1-4128-2090-5.

- ^ "Lo que brilla con luz propia, nada lo puede apagar". Granma Cuba Si (in Spanish). Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- ^ "Desembarco del Granma National Park". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- ^ Expedición del Granma. Cuban Ministry of the Armed Forces. Retrieved November 19, 2006.

- ^ Enrique Oltuski (November 29, 2002). Vida Clandestina: My Life in the Cuban Revolution. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 292–. ISBN 978-0-7879-6658-4.

Works cited[]

- "A Ragtag Revolution". The Cuba Libre Story. Episode 4 (in Finnish). 2016. Yle.

- Swanson, Peter (February 23, 2018). "The Amazing True Story of Fidel Castro's Mystery Motoryacht". PassageMaker.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Granma (ship, 1943). |

- Motor yachts

- Cuban Revolution

- Museum ships in Cuba

- Che Guevara