Great Hymn to the Aten

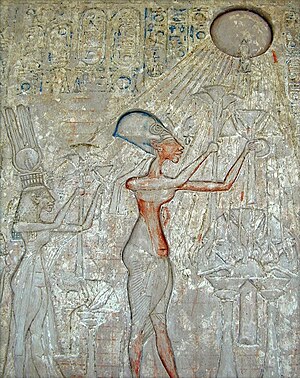

The Great Hymn to the Aten is the longest of a number of hymn-poems written to the sun-disk deity Aten. Composed in the middle of the 14th century BC, it is varyingly attributed to the 18th Dynasty Pharaoh Akhenaten or his courtiers, depending on the version, who radically changed traditional forms of Egyptian religion by replacing them with Atenism.[1]

The hymn-poem provides a glimpse of the religious artistry of the Amarna period expressed in multiple forms encompassing literature, new temples, and in the building of a whole new city at the site of present-day Amarna as the capital of Egypt. Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson said that "It has been called 'one of the most significant and splendid pieces of poetry to survive from the pre-Homeric world.'"[2] Egyptologist John Darnell asserts that the hymn was sung.[3]

Various courtiers' rock tombs at Amarna (ancient Akhet-Aten, the city Akhenaten founded) have similar prayers or hymns to the deity Aten or to the Aten and Akhenaten jointly. One of these, found in almost identical form in five tombs, is known as The Short Hymn to the Aten. The long version discussed in this article was found in the tomb of the courtier (and later Pharaoh) Ay.[4]

The 18th Dynasty Pharaoh Akhenaten forbade the worship of other gods, a radical departure from the centuries of Egyptian religious practice. Akhenaton's religious reforms (later regarded heretical and reversed under his successor Pharaoh Tutankhamun) have been described by some scholars as monotheistic, though others consider them to be henotheistic.[5]

Excerpts of the hymn-poem to Aten[]

These particular excerpts are not attributed to Aten himself, this long version was found in the tomb of the courtier Ay.[6]

From the middle of the text:

- How manifold it is, what thou hast made!

- They are hidden from the face (of man).

- O sole god, like whom there is no other!

- Thou didst create the world according to thy desire,

- Whilst thou wert alone: All men, cattle, and wild beasts,

- Whatever is on Earth, going upon (its) feet,

- And what is on high, flying with its wings.

- The countries of Syria and Nubia, the land of Egypt,

- Thou settest every man in his place,

- Thou suppliest their necessities:

- Everyone has his food, and his time of life is reckoned.

- Their tongues are separate in speech,

- And their natures as well;

- Their skins are distinguished,

- As thou distinguishest the foreign peoples.

- Thou makest a Nile in the underworld,

- Thou bringest forth as thou desirest

- To maintain the people (of Egypt)

- According as thou madest them for thyself,

- The lord of all of them, wearying (himself) with them,

- The lord of every land, rising for them,

- The Aton of the day, great of majesty.[7]

From the last part of the text, translated by Miriam Lichtheim:

- You are in my heart,

- There is no other who knows you,

- Only your son, Neferkheprure, Sole-one-of-Re [Akhenaten],

- Whom you have taught your ways and your might.

- [Those on] Earth come from your hand as you made them.

- When you have dawned they live.

- When you set they die;

- You yourself are lifetime, one lives by you.

- All eyes are on [your] beauty until you set.

- All labor ceases when you rest in the west;

- When you rise you stir [everyone] for the King,

- Every leg is on the move since you founded the Earth.

- You rouse them for your son who came from your body.

- The King who lives by Maat, the Lord of the Two Lands,

- Neferkheprure, Sole-one-of-Re,

- The Son of Re who lives by Maat. the Lord of crowns,

- Akhenaten, great in his lifetime;

- (And) the great Queen whom he loves, the Lady of the Two Lands,

- Nefer-nefru-Aten Nefertiti, living forever.[8]

Comparison to Psalm 104[]

In his 1958 book Reflections on the Psalms, C.S. Lewis compared Akhnaten's Hymn to the Psalms of the Judaeo-Christian canon. James Henry Breasted noted the similarity to Psalm 104,[9] which he believed was inspired by the Hymn.[10] Arthur Weigall compared the two texts side by side and commented that "In face of this remarkable similarity one can hardly doubt that there is a direct connection between the two compositions; and it becomes necessary to ask whether both Akhnaton’s hymn and this Hebrew psalm were derived from a common Syrian source, or whether Psalm civ. is derived from this Pharaoh’s original poem. Both views are admissible."[11] Lichtheim, however, said that the resemblances are "more likely to be the result of the generic similarity between Egyptian hymns and biblical psalms. A specific literary interdependence is not probable."[12] Biblical scholar Mark S. Smith has commented that "Despite enduring support for the comparison of the two texts, enthusiasm for even indirect influence has been tempered in recent decades. In some quarters, the argument for any form of influence is simply rejected outright. Still some Egyptologists, such as Jan Assmann and Donald Redford, argue for Egyptian influence on both the Amarna correspondence (especially in EA 147) and on Psalm 104."[13]

Analysis[]

Analyses of the poem are divided between those considering it as a work of literature, and those considering its political and socio-religious intentions.

James Henry Breasted considered Akhenaten to be the first monotheist and scientist in history. In 1899, Flinders Petrie wrote:

If this were a new religion, invented to satisfy our modern scientific conceptions, we could not find a flaw in the correctness of this view of the energy of the solar system. How much Akhenaten understood, we cannot say, but he certainly bounded forward in his views and symbolism to a position which we cannot logically improve upon at the present day. Not a rag of superstition or of falsity can be found clinging to this new worship evolved out of the old Aton of Heliopolis, the sole Lord of the universe.[14]

Miriam Lichtheim describes the hymn as "a beautiful statement of the doctrine of the One God."[15]

In 1913, Henry Hall contended that the pharaoh was the "first example of the scientific mind."[16]

Egyptologist Dominic Montserrat discusses the terminology used to describe these texts, describing them as formal poems or royal eulogies. He views the word 'hymn' as suggesting "outpourings of emotion" while he sees them as "eulogies, formal and rhetorical statements of praise" honoring Aten and the royal couple. He credits James Henry Breasted with the popularisation of them as hymns saying that Breasted saw them as "a gospel of the beauty and beneficence of the natural order, a recognition of the message of nature to the soul of man" (quote from Breasted).[17]

Montserrat argues that all the versions of the hymns focus on the king and suggests that the specific innovation is to redefine the relationship of god and king in a way that benefited Akhenaten, quoting the statement of Egyptologist John Baines that "Amarna religion was a religion of god and king, or even of king first and then god."[18][19]

Donald B. Redford argued that while Akhenaten called himself the son of the Sun-Disc and acted as the chief mediator between god and creation, kings for thousands of years before Akhenaten's time had claimed the same relationship and priestly role. However Akhenaten's case may be different through the emphasis placed on the heavenly father and son relationship. Akhenaten described himself as "thy son who came forth from thy limbs", "thy child", "the eternal son that came forth from the Sun-Disc", and "thine only son that came forth from thy body". The close relationship between father and son is such that only the king truly knows the heart of "his father", and in return his father listens to his son's prayers. He is his father's image on earth and as Akhenaten is king on earth his father is king in heaven. As high priest, prophet, king and divine he claimed the central position in the new religious system. Since only he knew his father's mind and will, Akhenaten alone could interpret that will for all mankind with true teaching coming only from him.[20]

Redford concluded:

Before much of the archaeological evidence from Thebes and from Tell el-Amarna became available, wishful thinking sometimes turned Akhenaten into a humane teacher of the true God, a mentor of Moses, a Christlike figure, a philosopher before his time. But these imaginary creatures are now fading away one by one as the historical reality gradually emerges. There is little or no evidence to support the notion that Akhenaten was a progenitor of the full-blown monotheism that we find in the Bible. The monotheism of the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament had its own separate development—one that began more than half a millennium after the pharaoh's death.[21]

Adaptations[]

- The "Hymn to the Aten" was set to music by Philip Glass in his 1984 opera Akhnaten.

See also[]

- Moses and Monotheism

- Hermetica

References[]

- ^ Lichtheim, Miriam (2006). Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume II: The New Kingdom. University of California Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0520248434.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby (2011). The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 289–290. ISBN 978-1408810026.

- ^ Darnell>[1], John (3 August 2007). Tutankhamun's Armies: Battle and Conquest During Ancient Egypt's Late Eighteenth Dynasty. p. 41. ISBN 978-0471743583.

{{cite book}}: External link in|last= - ^ Lichtheim, Miriam (2006). Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume II: The New Kingdom. University of California Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0520248434.

- ^ Brewer, Douglas j.; Emily Teeter (22 February 2007). Egypt and the Egyptians (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-521-85150-3.

- ^ Lichtheim, Miriam (2006). Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume II: The New Kingdom. University of California Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0520248434.

- ^ Pritchard, James B., ed., The Ancient Near East – Volume 1: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1958, pp. 227-230.

- ^ Lichtheim, Miriam (2006). Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume II: The New Kingdom (2nd Ref. ed.). University of California Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0520248434.

- ^ Breasted, James Henry (2008). A History of the Ancient Egyptians (repr. ed.). Kessinger Publishing. p. 273. ISBN 978-1436570732.

- ^ Montserrat, Dominic (2002). Akhenaten: History, Fantasy and Ancient Egypt. Routledge. p. 101. ISBN 978-0415301862.

- ^ The Life and Times of Akhnaton. Arthur E. P. Weigall. pp. 155–156.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Lichtheim, Miriam (2006). Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume II: The New Kingdom. University of California Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0520248434.

- ^ Smith, Mark S. (2010). God in Translation: Deities in Cross-Cultural Discourse in the Biblical World. William B Eerdmans Publishing. p. 70. ISBN 978-0802864338. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ Sir Flinders Petrie, History of Egypt (edit. 1899), Vol. II, p. 214.

- ^ Lichtheim, Miriam (2006). Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume II: The New Kingdom (2nd Ref. ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520248434.

- ^ H. R. Hall, Ancient History of the Near East (1913), p. 599.

- ^ Montserrat, Dominic (2002). Akhenaten: History, Fantasy and Ancient Egypt. Routledge. p. 38. ISBN 978-0415301862.

- ^ Montserrat, Dominic (2002). Akhenaten: History, Fantasy and Ancient Egypt. Routledge. p. 40. ISBN 978-0415301862.

- ^ John Baines (1998). "The Dawn of the Amarna Age". In David O'Connor, Eric Cline (ed.). Amenhotep III: Perspectives on His Reign. University of Michigan Press. p. 281.

- ^ "The Monotheism of the Heretic Pharaoh: Precursor of Mosaic monotheism or Egyptian anomaly?", Donald B. Redford, Biblical Archaeology Review, May–June edition 1987

- ^ "Aspects of Monotheism", Donald B. Redford, Biblical Archaeology Review, 1996

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Great Hymn to the Aten |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Great Hymn to the Aten. |

- Geoffrey Graham, copied from Sandman Holmberg, Maj (1938). Texts from the time of Akhenaten. Bibliotheca aegyptiaca. Vol. 8. Brussels: Fondation Egyptologique Reine Elisabeth. p. 93–96. ISSN 0067-7817.

- de Garis Davies, Norman (1908). The Rock Tombs of El Amarna: Tombs of Parennefer, Tutu, and Aÿ. Archaeological survey of Egypt. London: Egypt Exploration Society. Plate xxvii. Also available from rostau.org.uk.

- Comparison between the Egyptian Hymn of Aten and modern scientific conceptions

- Atenism

- Ancient Egyptian hymns

- Akhenaten