Gudea cylinders

The Gudea cylinders are a pair of terracotta cylinders dating to circa 2125 BC, on which is written in cuneiform a Sumerian myth called the Building of Ningirsu's temple.[1] The cylinders were made by Gudea, the ruler of Lagash, and were found in 1877 during excavations at Telloh (ancient Girsu), Iraq and are now displayed in the Louvre in Paris, France. They are the largest cuneiform cylinders yet discovered and contain the longest known text written in the Sumerian language.[2]

Compilation[]

Discovery[]

The cylinders were found in a drain by Ernest de Sarzec under the Eninnu temple complex at Telloh, the ancient ruins of the Sumerian "holy city" of Girsu, during the first season of excavations in 1877. They were found next to a building known as the , where a brick pillar (pictured) was found containing an inscription describing its construction by Gudea within Eninnu during the Second Dynasty of Lagash. The Agaren was described on the pillar as a place of judgement, or mercy seat, and it is thought that the cylinders were either kept there or elsewhere in the Eninnu. They are thought to have fallen into the drain during the destruction of Girsu generations later.[3] In 1878 the cylinders were shipped to Paris, France where they remain on display today at the Louvre, Department of Near East antiquities, Richelieu, ground floor, room 2, accession numbers MNB 1511 and MNB 1512.[3]

Description[]

The two cylinders were labelled A and B, with A being 61 cm high with a diameter of 32 cm and B being 56 cm with a diameter of 33 cm. The cylinders were hollow with perforations in the centre for mounting. These were originally found with clay plugs filling the holes, and the cylinders themselves filled with an unknown type of plaster. The clay shells of the cylinders are approximately 2.5 to 3 cm thick. Both cylinders were cracked and in need of restoration and the Louvre still holds 12 cylinder fragments, some of which can be used to restore a section of cylinder B.[3] Cylinder A contains thirty columns and cylinder B twenty four. These columns are divided into between sixteen and thirty-five cases per column containing between one and six lines per case. The cuneiform was meant to be read with the cylinders in a horizontal position and is a typical form used between the Akkadian Empire and the Ur III dynasty, typical of inscriptions dating to the 2nd Dynasty of Lagash. Script differences in the shapes of certain signs indicate that the cylinders were written by different scribes.[3]

Translations and commentaries[]

Detailed reproductions of the cylinders were made by Ernest de Sarzec in his excavation reports which are still used in modern times. The first translation and transliteration was published by Francois Threau-Dangin in 1905.[4] Another edition with a notable concordance was published by Ira Maurice Price in 1927.[5] Further translations were made by M. Lambert and R. Tournay in 1948,[6] Adam Falkenstein in 1953,[7] Giorgio Castellino in 1977,[8] Thorkild Jacobsen in 1987,[1] and Dietz Otto Edzard in 1997.[9] The latest translation by the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (ETCSL) project was provided by Joachim Krecher with legacy material from Hermann Behrens and Bram Jagersma.[10] Samuel Noah Kramer also published a detailed commentary in 1966[11] and in 1988.[12] Herbert Sauren proposed that the text of the cylinders comprised a ritual play, enactment or pageant that was performed during yearly temple dedication festivities and that certain sections of both cylinders narrate the script and give the ritual order of events of a seven-day festival.[13] This proposition was met with limited acceptance.[14]

Composition[]

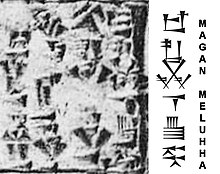

Interpretation of the text faces substantial limitations for modern scholars, who are not the intended recipients of the information and do not share a common knowledge of the ancient world and the background behind the literature. Irene Winter points out that understanding the story demands "the viewer's prior knowledge and correct identification of the scene – a process of 'matching' rather than 'reading' of imagery itself qua narrative." The hero of the story is Gudea (statue pictured), king of the city-state of Lagash at the end of the third millennium BC. A large quantity of sculpted and inscribed artifacts have survived pertaining to his reconstruction and dedication of the Eninnu, the temple of Ningursu, the patron deity of Lagash. These include foundation nails (pictured), building plans (pictured) and pictorial accounts sculpted on limestone stelae. The temple, Eninnu was a formidable complex of buildings, likely including the E-pa, Kasurra and sanctuary of Bau among others. There are no substantial architectural remains of Gudea's buildings, so the text is the best record of his achievements.[3]

Cylinder X[]

Some fragments of another Gudea inscription were found that could not be pieced together with the two in the Louvre. This has led some scholars to suggest that there was a missing cylinder preceding the texts recovered. It has been argued that the two cylinders present a balanced and complete literary with a line at the end of Cylinder A having been suggested by Falkenstein to mark the middle of the composition. This colophon has however also been suggested to mark the cylinder itself as the middle one in a group of three. The opening of cylinder A also shows similarities to the openings of other myths with the destinies of heaven and earth being determined. Various conjectures have been made regarding the supposed contents of an initial cylinder. Victor Hurowitz suggested it may have contained an introductory hymn praising Ningirsu and Lagash.[15] Thorkild Jacobsen suggested it may have explained why a relatively recent similar temple built by Ur-baba (or Ur-bau), Gudea's father-in-law "was deemed insufficient".[1]