Gulliver's Travels Beyond the Moon

| Gulliver's Travels Beyond the Moon | |

|---|---|

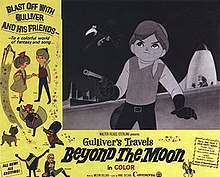

Theatrical poster to the 1966 US release of Gulliver's Travels Beyond the Moon | |

| Directed by | |

| Written by | Shinichi Sekizawa Jonathan Swift (novel Gulliver's Travels) Hayao Miyazaki (additional screenplay material; uncredited) |

| Produced by | Hiroshi Ogawa |

| Starring | voices: (US) (US) Darla Hood (US) (Japan) (Japan) Seiji Miyaguchi (Japan) (Japan) Shoichi Ozawa (Japan) Kyū Sakamoto |

| Music by | Isao Tomita (Japanese version) (US version) Milton DeLugg (US version) |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Toei (Japan) Continental Distributing Inc. (1966 US) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 80 min. 85 min. (US) |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

Gulliver's Travels Beyond the Moon (ガリバーの宇宙旅行, Garibā no Uchū Ryokō, Gulliver's Space Travels), also known as Space Gulliver, is a 1965 Japanese animated feature that was released in Japan on March 20, 1965 and in the United States on July 23, 1966.[1]

Plot[]

The story concerns a homeless boy named Ricky, or Ted in the Japanese version. Whilst seeing a movie about Lemuel Gulliver he is discovered to have entered without buying a ticket and he is thrown out onto the street. Ejected and dejected, he is then nearly run over by a truck, but is knocked unconscious when he is thrown against a wall. He awakes to find a talking dog and then the Colonel, a talking clockwork toy soldier who has been discarded in a rubbish bin. The dog suggests the trio amuse themselves at an amusement park that is closed for the night.

The trio enjoy themselves on the rides and in a planetarium but are pursued by three security guards. The boy, his dog and the Colonel escape on fireworks rockets that land them in the countryside. They meet Professor Gulliver himself in a forest. Gulliver is now an elderly, space-traveling scientist who has built a rocket ship. With Dr. Gulliver's assistant Sylvester the crow (named Crow in the Japanese edition), Gulliver and the trio travel the Milky Way to the Planet of Blue Hope. They discover the planet has been taken over by the Queen of the Purple Planet and her evil group of robots, who the inhabitants of the Blue Planet created to make themselves a life of leisure that turned into a nightmare when the robots overthrew the population of the Blue Planet and seized control. Armed with water-pistols and water balloons which melt the villains, Ricky and Gulliver restore the Planet of Blue Hope to its doll-like owners who regain life as human beings.

The boy wakes up in the street. He meets his canine companion who now is an ordinary dog who can not talk and discovers the non-talking non-living Colonel in the rubbish bin. The three walk down the street looking for a new adventure.

Production[]

This was one of the first Toei animated features to depart from Asian mythology, though, like Toei's previous animated features, it is modeled after the Disney formula of animated musical feature. By borrowing elements from Hans Christian Andersen, Jonathan Swift and science fiction, it was hoped that this film would attract a large international audience. However it proved to be no more popular than Toei's previous, Asian-themed films. After the failure in the U.S. of this and Toei's previous animated feature[clarification needed], this was the last Japanese animated feature to be released in the United States for over a decade, until Sanrio's Metamorphoses and The Mouse and His Child, both of which were released in the U.S. in 1978.[2]

Staff[]

Not yet the internationally popular electronic music composer he was later to become, Isao Tomita contributed the original Japanese score. However, for the American edition, songs were composed by Milton and Anne Delugg, who had provided the song "Hooray for Santy Claus" for Santa Claus Conquers the Martians (1964).

In one of his earliest animation jobs, a young Hayao Miyazaki worked on this film as an in-between artist. His contribution to the ending of the film brought Miyazaki to the attention of Toei. The screenplay was written by Shinichi Sekizawa, the writer of the first Mothra (1961). Sekizawa also contributed screenplays to some of the most popular films in the Godzilla series from King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962), to Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla (1974), including Mothra vs. Godzilla (1964).

In the English language version, former Our Gang star Darla Hood provides the voice of the Princess.

Reception and Home Media[]

In a contemporary review, the Monthly Film Bulletin reviewed an 85-minute English-language dubbed version of the film, and described it as a "charmless animated feature".[3] The review described the animation as "mediocre" and with "little variation or invention and a noticeable lack of perspective"[3]

released the film on US DVD (no year given)

English soundtrack[]

Milton DeLugg composed the score for the English language version of the film. Milton and his wife Anne Delugg co-wrote seven songs, and their son Stephen providing the voice of "Ricky". The songs are:

- "Think Tall"

- "The Earth Song"

- "I Wanna Be Like Gulliver!"

- "That's the Way It Goes"

- "Keep Your Hopes High"

- "Rise, Robots, Rise"

- "Deedle Dee Dum"

References[]

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. pp. 181–182. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Beck, Jerry (2005). The animated movie guide. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. p. 101. ISBN 1-55652-591-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Garibah no Uchu Ryoko (Gulliver's Travels Beyond the Moon)". Monthly Film Bulletin. Vol. 37 no. 432. British Film Institute. 1970. p. 128.

Further reading[]

- Beck, Jerry (2005). The animated movie guide. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 1-55652-591-5.

- Clements, Jonathan and Helen McCarthy (2001). The anime encyclopedia: a guide to Japanese animation since 1917. Berkeley, Calif: Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 1-880656-64-7.

External links[]

- Gariba no uchu ryoko at IMDb

- Gulliver's Travels Beyond the Moon at AllMovie

- Gulliver no Uchū Ryokō (anime) at Anime News Network's encyclopedia

- 1965 films

- Japanese-language films

- 1965 anime films

- 1960s fantasy adventure films

- Adventure anime and manga

- Animated adventure films

- Japanese fantasy adventure films

- Fantasy anime and manga

- Films based on Gulliver's Travels

- Japanese films

- Japanese animated fantasy films

- Toei Animation films

- Toei Company films

- Animated films about extraterrestrial life