Gustavus Hesselius

Gustavus Hesselius | |

|---|---|

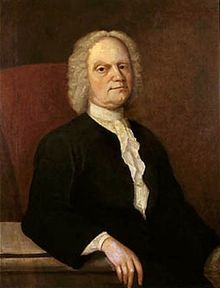

Self portrait, ca 1740 | |

| Born | Gustaf Hesselius 1682 Folkärna, Dalarna, Sweden |

| Died | May 25, 1755 |

| Nationality | |

| Known for | Painting |

Gustavus Hesselius (1682 – May 25, 1755) was a Swedish-American painter. He was European trained and became a leading artist in the mid-Atlantic colonies during the first half of the eighteenth century. He was among the earliest portrait painter and organ builder in the United States. He was named to the Prince George's County Hall of Fame by the Prince George's County Historical Society.[1][2] [3] [4] [5]

Biography[]

Hesselius was born in Folkärna parish at Avesta in Dalarna County, Sweden. He was the son of Andreas Olai Hesselius (1644-1700) and his wife Maria Bergia (c. 1658-1717). His father was the vicar at Folkärna Church. His mother was the sister-in-law of Jesper Swedberg (1653–1735), Bishop of the Diocese of Skara and aunt of religious leader Emanuel Swedenborg. [6] [7] [8]

Hesselius had studied art in Sweden and probably in England. He came to Wilmington, Delaware in 1711 together with his elder brother Andreas Hesselius (1677-1733). His brother had been appointed to become parish priest of Holy Trinity Church, the Swedish Lutheran parish at Fort Christina.[7][9]

He lived in Delaware until 1717, then moved to Philadelphia where he lived until 1721. In 1721, he moved to Prince George's County, Maryland and became a portrait painter. That same year, he received the first recorded public art commission in the American colonies; he painted The Last Supper. He also painted a Crucifixion. Some time around 1735, Hesselius returned to Philadelphia where he spent the rest of his life.[3]

He also worked as an organ builder, having built an organ for the Moravian Church in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania in 1746. From about this time on, he focused on building organs with the assistance of John Clemm (1690–1762).[10] He referred painting commissions to his son John.[3]

Personal life[]

Gustavus Hesselius was married to Lydia Getchie (1684-1755). He was the father of painter John Hesselius (1728–1778). His granddaughter Elizabeth Henderson was married to artist Adolf Ulrik Wertmüller (1751-1811). Hesselius was listed as a member of the Gloria Dei (Old Swedes') Church in Philadelphia. He died during 1755 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and was buried on the 25th at Gloria Dei Church.[11][12][13]

Style[]

While most of his portraits adhere to the formality typical for American portrait painting of his time, according to Michael J. Lewis, his portrait of Lappawinsoe, chief of the Lenape, was among the first to foreshadow "the sympathetic and unaffected realism" that would later develop in American portraiture. The painter was able to ignore the rigid conventions of colonial society because Lappawinsoe was a member of a First Nation.[14][15]

The Last Supper[]

The Last Supper by Gustavus Hesselius was the first recorded public art commission in the American colonies. Commissioned in October 1721, it is displayed on the choir gallery of St. Barnabas Church, Upper Marlboro, Maryland.[3][16][17] Before this, most painting in the new world had been portraits. The Last Supper was the first significant American painting to depict a scene.[16]

The painting which measures 35 inches by 117½ inches[17] was commissioned for an older church built in 1710, and remained there until the present structure was built in 1774.[18] It disappeared during the construction of the new Brick Church and did not surface again until it was discovered in a private collection in 1848[16] or 1914, when Charles Henry Hart identified it,[17] depending on which source one follows.

It was on loan by Rose Neel Warrington for a period at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and at the American Swedish Historical Museum[16] as well as the Exhibition of Early American Paintings at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences in 1917 and the Wilmington Society of the Fine Arts.[17] The painting was willed once again to St. Barnabas upon Warrington's death.[16]

Gallery[]

Portrait of Lappawinsoe, (1735).

Portrait of Benjamin Fendall I

Portrait of Eleanor Fendall

Portrait of Mary Darnall Carroll

Portrait of Dr. Gustavus Brown; attributed to Gustavus Hesselius

Portrait of Mrs. Gustavus Brown; attributed to Gustavus Hesselius

Portrait of Lawrence Washington

Other significant works[]

- Lapowinsa, by Gustavus Hessulius, c. 1735. Oil on canvas, 33 × 25 in (83.8 × 63.5 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia.

- Tishcohan, by Gustavus Hessulius, c. 1735. Oil on canvas, 33 × 25 in (83.8 × 63.5 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia.

- Thomas Bordley, by Gustavus Hesselius, c. 1715. Oil on canvas. 27 × 22 41/64 in.(68.6 × 57.5 cm). Maryland Historical Society Accession: 1891-2-1[3]

- Mrs. Charles Carroll, the "Settler"', by Gustavus Hesselius, c. 1717–1720. Oil on canvas. 30 7/64 × 25 13/64 in. (76.5 × 64.0 cm). Maryland Historical Society Accession: 1949-64-1[3]

- Col. Leonard Hollyday, by Gustavus Hesselius, c. 1740. Oil on canvas. 27 55/64 × 23 7/64 in. (70.8 × 58.7 cm). Maryland Historical Society, Accession: 1960-88-1[3]

References[]

- ^ "The Prince George's Hall of Fame". Prince George's County Historical Society. 2003. Retrieved 2017-10-27.

- ^ "J. Hall Pleasants Papers, 1773-1957". Maryland Historical Society. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Maryland ArtSource - Artists - Gustavus Hesselius". The Baltimore Art Research & Outreach Consortium. Archived from the original on May 19, 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- ^ "Hesselius, Gustaf H". Nordisk familjebok. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ "Gustavus Hesselius. The Earliest Painter and Organ-Builder in America". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. Vol. XXIX. 1905. No. 2. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ "Folkärna Kyrka" (PDF). svenskakyrkan. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ a b "Hesselius, släkt". Svenskt biografiskt lexikon. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ "Swedberg, Jesper". The American Cyclopædia (1879). Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ "Hesselius, Andreas 1677-1733". Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ Baker 1992, p. 340.

- ^ "John Hesselius (1728-1778)". American Gallery. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ "Adolf Ulrich Wertmüller (1751–1811)". American Gallery – 18th Century. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ "Gustavius Hesselius". Historic Gloria Dei Preservation Corporation. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ Lewis, Michael J. (2006). American art and architecture. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 28. ISBN 0-500-20391-1.

- ^ "Lapowinsa, 1735" (PDF). National Humanities Center. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Virta, Alan (1984). Prince George's County: A Pictorial History. Norfolk, Virginia: The Donning Company. pp. 67–69. ISBN 0-89865-812-8.

- ^ a b c d Marceau, Henri (1931). "Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum, Vol. 26, No. 142, Part 1". Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum. Pennsylvania Museum of Art. 26 (142): 10–13. doi:10.2307/3794543. JSTOR 3794543.

- ^

"St. Barnabas Episcopal Church, Maryland Historical Trust, Historic Sites Survey # PG:79-59". Maryland State Archives. Archived from the original (web database) on 2007-09-05. Retrieved 2007-09-27. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

Other sources[]

- Fleischer, Roland E (1987) Gustavus Hesselius: Face Painter to the Middle Colonies (Trenton: New Jersey State Museum) ISBN 978-0938766063

Related reading[]

- Baker, Theodore (1992). Baker's Biographical Dictionary. Schirmer Books. ISBN 978-0-02-872415-7.

- Richard H. Saunders and Ellen G. Miles (1987) American Colonial Portraits, 1700–1776 (Washington, D.C.: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution) ISBN 9780874746952

- Pleasants, J. Hall (1945) Two Hundred and Fifty Years of Painting in Maryland (Baltimore, Maryland: Baltimore Museum of Art)

- Lindsey, Jack L., Worldly Goods, The Arts of Early Pennsylvania, 1680–1758 (Philadelphia, PA: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1999) ISBN 978-0876331293

- Benson, Adolph B. and Naboth Hedin (1938) Swedes in America, 1638-1938 (Yale University Press) ISBN 978-0-8383-0326-9

External links[]

- "Hesselius Family Papers, 1780-1820s", The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives.

- Gustavus Hesselius Smithsonian American Art Museum

- 1682 births

- 1755 deaths

- People from Dalarna County

- Swedish emigrants to the United States

- 18th-century Swedish painters

- Swedish male painters

- People from Prince George's County, Maryland

- 18th-century American painters

- American male painters

- Artists from Philadelphia

- Painters from Maryland

- Painters from Pennsylvania

- American pipe organ builders