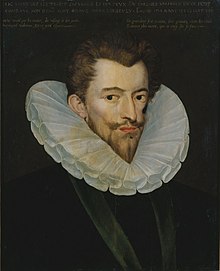

Henry I, Duke of Guise

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2011) |

| Henry I | |

|---|---|

| Grand Master of France Prince of Joinville Count of Eu | |

| |

| Duke of Guise | |

| Reign | 24 February 1563 – 23 December 1588 |

| Predecessor | Francis, Duke of Guise |

| Successor | Charles, Duke of Guise |

| Born | 31 December 1550 |

| Died | 23 December 1588 (aged 37) Château de Blois, Blois, France |

| Spouse | Catherine of Cleves |

| Issue among others... | |

| House | Guise |

| Father | Francis, Duke of Guise |

| Mother | Anna d'Este |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Henry I, Prince of Joinville, Duke of Guise, Count of Eu (31 December 1550 – 23 December 1588), sometimes called Le Balafré (Scarface), was the eldest son of Francis, Duke of Guise, and Anna d'Este. His maternal grandparents were Ercole II d'Este, Duke of Ferrara, and Renée of France. Through his maternal grandfather, he was a descendant of Lucrezia Borgia and Pope Alexander VI.

In 1576 he founded the Catholic League to prevent the heir, King Henry of Navarre, head of the Huguenot movement, from succeeding to the French throne. A key figure in the French Wars of Religion, he was one of the namesakes of the War of the Three Henrys. A powerful opponent of the queen mother, Catherine de' Medici, he was assassinated by the bodyguards of her son, King Henry III.

Early life[]

Henry I was born on 31 December 1550, the eldest son of Francis Duke of Guise, one of the leading magnates of France, and Anna d'Este, daughter of the Duke of Ferrara. In his youth he was friends with Henry III, the future king, and at the behest of Jacques, Duke of Nemours tried to persuade the young prince to run away with him in 1561 to join the arch-Catholic faction, much to the fury of his father and uncle.[1] At the age of 12 his father was assassinated and he thus inherited the Duke's titles of the Governor of Champagne and Grand Maitre de France in 1563.[2] The Guise family and Henry craved vengeance against Gaspard II de Coligny, whom they considered responsible for the assassination.[3]

As such he and his uncle Charles, Cardinal of Lorraine would attempt to make a show of force in entering Paris in 1564, but their entry ended with both besieged in their residence and forced to concede.[4] When in 1566 the crown forced Charles at Moulins to make the kiss of peace with Coligny to end their feud, Henry refused to attend.[5] He would also challenge Coligny and Anne de Montmorency to duels, but they rebuffed his attempts.[5]

No longer welcome at court, he and his brother Charles, Duke of Mayenne decided to crusade against the Ottoman Empire in Hungary, serving under Alfonso II d'Este, with a retinue of 350 men.[5] In September 1568 he reached his majority, just as the Guise returned to the centre of French politics with his uncle's readmission to the Privy Council.[5][6]

Entry into politics[]

Henry took an active military role in the second and third wars of the French Wars of Religion, fighting at the Battle of Saint-Denis in 1567, the Battle of Jarnac in 1569, and successfully defending Poitiers during a siege by Admiral Coligny.[7] He was wounded at the Battle of Moncontour.[8]

In 1570 the third war of religion was brought to an end with the Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, part of which stipulated a marriage between the Protestant Henry IV of Navarre and the King's sister Margaret of Valois as a means of ensuring stability.[9] Around this time Henry began an affair with her, which quickly became known around court.[9] Upon discovering this her brothers, Charles IX and Henry, were furious, assaulting Margaret in anger.[10] While some suggested Henry be punished with assassination, it was settled on banishing him from court for his indiscretions.[9] On 3 October he married Catherine of Cleves, thus assuming the title of Count of Eu from her inheritance.[11]

The August 1572 marriage between Henry IV and Margaret necessitated the presence of the majority of the Protestant leadership in Paris.[12] Shortly after the wedding, Coligny, who had made a rare visit to the capital for the occasion, was shot in the shoulder in an attempted assassination. Henry was a chief suspect of having ordered the attempt, due to his long running feud.[13]

As the situation in Paris deteriorated over the next several days, the royal council planned and executed a targeted elimination of the Protestant leadership in Paris, which would spiral into the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre.[14] During the massacre Henry would oversee the murder of Coligny, and attempted but failed to capture several other targets, but was displeased at the situation descending into a general massacre, shielding fleeing Protestants in his residence.[15][14]

When the wars of religion subsequently resumed Henry was wounded at the Battle of Dormans, and was thereafter known, like his father, as "Le Balafré".[16] With a charismatic and brilliant public reputation, he rose to heroic stature among the militant Catholic population of France as an opponent of the Huguenots.

Catholic League[]

In 1576 he formed the Catholic League.[citation needed] His rapidly deteriorating relations with the new King Henry III created further conflict, known as the War of the Three Henries (1584–1588).

At the death in 1584 of Francis, Duke of Anjou, the king's brother (which left Henry of Navarre, the Protestant champion, as heir-male), Guise concluded the Treaty of Joinville with Philip II of Spain. This compact declared that the Cardinal de Bourbon should succeed Henry III, in preference to Henry of Navarre. Henry III now sided with the Catholic League (1585), which made war with great success on the Protestants. Guise sent his cousin, Charles, Duke of Aumale, to lead a rising in Picardy (which could also support the retreat of the Spanish Armada). Alarmed, Henry III ordered Guise to remain in Champagne; he defied the king and on 9 May 1588 Guise entered Paris, bringing to a head his ambiguous challenge to royal authority in the Day of the Barricades and forcing King Henry to flee.

Assassination[]

The League now controlled France; the king was forced to accede to its demands and created Guise Lieutenant-General of France. But Henry III refused to be treated as a mere puppet by the League, and decided upon a bold stroke. On 22 December 1588, Guise spent the night with his current mistress Charlotte de Sauve, the most accomplished and notorious member of Catherine de' Medici's group of female spies known as the "Flying Squadron".[17] The following morning at the Château de Blois, Guise was summoned to attend the king, and was at once assassinated by "the Forty-five", the king's bodyguard, as Henry III looked on.[18] Guise's brother, Louis II, Cardinal of Guise, was likewise assassinated the next day. The deed aroused such outrage among the remaining relatives and allies of Guise that Henry III was forced to take refuge with Henry of Navarre. Henry III was assassinated the following year by Jacques Clément, an agent of the Catholic League.

According to Baltasar Gracián in A Pocket Mirror for Heroes, it was once said of him to Henry III, "Sire, he does good wholeheartedly: those who do not receive his good influence directly receive it by reflection. When deeds fail him, he resorts to words. There is no wedding he does not enliven, no baptism at which he is not godfather, no funeral he does not attend. He is courteous, humane, generous, the honorer of all and the detractor of none. In a word, he is a king by affection, just as Your Majesty is by law."

Issue[]

He married on 4 October 1570 in Paris to Catherine of Cleves (1548–1633), Countess of Eu,[19] by whom he had fourteen children:

- Charles, Duke of Guise (1571–1640), who succeeded him[20]

- Henri (30 June 1572, Paris – 3 August 1574)

- Catherine (3 November 1573) (died at birth)

- Louis III, Cardinal of Guise (1575–1621), Archbishop of Reims[20]

- Charles (1 January 1576, Paris) (died at birth)

- Marie (1 June 1577 – 1582)

- Claude, Duke of Chevreuse (1578–1657) married Marie de Rohan,[20] daughter of Hercule de Rohan, duc de Montbazon

- Catherine (b. 29 May 1579), died young

- Christine (21 January 1580) (died at birth)

- François (14 May 1581 – 29 September 1582)

- Renée (1585 – 13 June 1626, Reims), Abbess of St. Pierre[20]

- Jeanne (31 July 1586 – 8 October 1638, Jouarre), Abbess of Jouarre[20]

- Louise Marguerite, (1588 – 30 April 1631, Château d'Eu), married on 24 July 1605 François, Prince of Conti[20]

- François Alexandre (7 February 1589 – 1 June 1614, Château des Baux),[20] a Knight of the Order of Malta

In literature and the arts[]

Literature[]

The Duke of Guise appears as an archetypal Machiavellian schemer in Christopher Marlowe's The Massacre at Paris, which was written about 20 years[21] after the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre. The death of the duke is also mentioned, by the ghost of Machiavelli himself, in the opening lines of The Jew of Malta. He appears (as The Guise) in George Chapman's Bussy D'Ambois and its sequel, The Revenge of Bussy D'Ambois.

John Dryden and Nathaniel Lee wrote The Duke of Guise (1683),[22] based on events during the reign of Henry III of France.

He appears in the short novel The Princess of Montpensier, by Madame de La Fayette. He appears in Voltaire's epic poem "La Henriade" (1723). He is one of the characters in Alexandre Dumas's novel La Reine Margot and its sequels, La Dame de Monsoreau and The Forty-Five Guardsmen. He also appears prominently in Heinrich Mann's novel Young Henry of Navarre (1935).

Stanley Weyman's novel A Gentleman of France includes the Duke of Guise in its tale about the War of the Three Henries.

Ken Follett's novel A Column of Fire features Henry, Duke of Guise as a prominent character, and explores his involvement with the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre.

Literature[]

- Pierre Matthieu, (1589).

- Christopher Marlowe, The Massacre at Paris (1593).

- George Chapman, The Tragedy of Bussy D'Ambois (1607).

- George Chapman, The Revenge of Bussy D'Ambois (1613).

- John Dryden & Nathaniel Lee, The Duke of Guise (1683).

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Carroll, Stuart (2009). Martyrs and Murderers: The Guise Family and the Making of Europe. oxford university press. p. 186. ISBN 978-0199229079.

- ^ Carroll, Stuart (2009). Martyrs and Murderers: The Guise Family and the Making of Europe. Oxford University Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-0199229079.

- ^ Carroll, Stuart (2009). Martyrs and Murderers: The Guise Family and the Making of Europe. Oxford University Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0199229079.

- ^ Carroll, Stuart (2009). Martyrs and Murderers: The Guise Family and the Making of Europe. Oxford University Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0199229079.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Carroll, Stuart (2009). Martyrs and Murderers: The Guise Family and the Making of Europe. Oxford University Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0199229079.

- ^ Carroll, Stuart (2009). Martyrs and Murderers: The Guise Family and the Making of Europe. Oxford University Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-0199229079.

- ^ Carroll 2011, p. 187.

- ^ Thompson 1915, p. 388-389.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Carroll, Stuart (2009). Martyrs and Murderers: The Guise Family and the Making of Europe. Oxford University Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-0199229079.

- ^ Wellman, Katherine (2013). Queens and Mistresses of Renaissance France. Yale University Press. p. 280. ISBN 978-0300178852.

- ^ Carroll, Stuart (2009). Martyrs and Murderers: The Guise Family and the Making of Europe. Oxford University Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0199229079.

- ^ Thompson, James (1909). The Wars of Religion in France, 1559-76: The Huguenots, Catherine de Medici and Phillip II. University of Chicago Press. p. 449.

- ^ Sutherland, Nicola (1973). The Massacre of St Bartholomew and the European Conflict 1559-72. Macmillan. p. 312. ISBN 0064966208.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Knecht, Robert (2010). The French Wars of Religion 1559-98. Routledge. p. 49. ISBN 9781408228197.

- ^ Carroll, Stuart (2009). Martyrs and Murderers: The Guise Family and the Making of Europe. pp. 217–8. ISBN 9780199596799.

- ^ Richards 2016, p. 176-177.

- ^ Strage 1976, p. 277.

- ^ Strage 1976, p. 277-278.

- ^ Carroll 1998, p. 27.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Spangler 2016, p. 272.

- ^ OUP Complete Works of Christopher Marlowe 1998. pp. 294–295

- ^ Dryden, John. The works, vol 14: Plays, 1993. Los Angeles: University of California, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 22 February 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link).

Sources[]

- Carroll, Stuart (1998). Noble Power During French Wars of Religion: The Guise Affinity and the Catholic Cause in Normandy. Cambridge University Press.

- Carroll, Stuart (2011). Martyrs and Murderers:The Guise Family and the Making of Europe. Oxford University Press.

- Richards, Penny (2016). "Warriors of God: History, Heritage and the Reputation of the Guise". In Munns, Jessica; Richards, Penny; Spangler, Jonathan (eds.). Aspiration, Representation and Memory: The Guise in Europe, 1506–1688. Routledge. pp. 169–182.

- Spangler, Jonathan (2016). The Society of Princes: The Lorraine-Guise and the Conservation of Power and Wealth in Seventeenth-Century France. Routledge.

- Strage, Mark (1976). Women of Power: The Life and Times of Catherine de' Medici. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Thompson, James Westfall (1915). The Wars of Religion in France, 1559-1576. Frederick Ungar Publishing Co.

External links[]

Media related to Henry I, Duke of Guise at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Henry I, Duke of Guise at Wikimedia Commons

- 1550 births

- 1588 deaths

- Assassinated French politicians

- Counter-Reformation

- Counts of Eu

- Dukes of Guise

- French generals

- French people of the French Wars of Religion

- French Roman Catholics

- Princes of Joinville

- People murdered in France

- Grand Masters of France