Higher education bubble in the United States

| This article is part of a series on |

| Education in the United States |

|---|

| Summary |

|

| Issues |

|

| Levels of Education |

|

|

|

The higher education bubble in the United States is a highly controversial claim that excessive investment in higher education could have negative repercussions in the broader economy. According to the claim, generally associated with fiscal conservatives,[1] although college tuition payments are rising, the supply of college graduates in many fields of study is exceeding the demand for their skills, which aggravates graduate unemployment and underemployment while increasing the burden of student loan defaults on financial institutions and taxpayers.[2][3] The claim has generally been used to justify cuts to public higher education spending, tax cuts, or a shift of government spending towards the criminal justice system and the Department of Defense.[4][5][6][7]

Most economists reject the notion of a higher education bubble, noting that the returns on higher education vastly outweigh the costs.[8][9][10][11]

Discussion[]

The "higher education bubble" is controversial and has been rejected by most economists. Data shows that the wage premium, the difference between what those with a four-year college degree earn and what those with only a high school education earn, has increased dramatically since the 1970s, but so has the 'debt load' incurred by students due to the tuition inflation.[8][9][10] Research from the Center for Household Financial Stability, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, presented in 2018, predicts a declining but still positive income premium for completing college but a declining wealth premium, which is almost indistinguishable from zero for the most recent cohort.[12] The data also suggests that, notwithstanding a slight increase in 2008–09, student loan default rates have declined since the mid-1980s and 1990s.[13][14] Those with college degrees are much less likely than those without to be unemployed, even though they are more expensive to employ (they earn higher wages).[15] The management consulting firm McKinsey & Company projects a shortage of college-educated workers and a surplus of workers without college degrees, which would cause the wage premium to increase and cause differences in unemployment rates to become even more dramatic.[16]

In 1971, Time ran the article "Education: Graduates and Jobs: A Grave New World" which stated that the supply of PhD students was 30 to 50 percent larger than the expected future demand in upcoming decades.[17] In 1987, U.S. Secretary of Education William Bennett suggested that the availability of loans may be fueling an increase in tuition prices and an education bubble.[18] This "Bennett hypothesis" claims that readily available loans allow schools to increase tuition without regard to demand elasticity. College rankings are partially driven by spending levels,[19] and higher tuition is also correlated with increased public perceptions of prestige.[20] Over the past thirty years, demand has increased as institutions improved facilities and provided more resources to students.[21]

A variation on the higher education bubble theory suggests that there is no general bubble in higher education (on average, higher education really does boost income and employment by more than enough to make it a good investment) but that degrees in some specific fields may be overvalued because they do little to boost income or improve job prospects, and degrees in other fields may in fact be undervalued because students do not appreciate the extent to which these degrees could benefit their employment prospects and future income. Proponents of the theory have noted that schools charge equal prices for tuition regardless of what students study, but the interest rate on federal student loans is not adjusted according to risk, and there is evidence that undergraduate students in their first three years of college are not very good at predicting future wages by major.[8]

A study from the Labor Department found that a bachelor's degree "represents a significant advantage in the job market."[22] In 2011, The Chronicle of Higher Education ran an article saying that the future is bright for college graduates.[23] Glenn Reynolds argued in his book, The Higher Education Bubble, that higher education as a "product grows more and more elaborate – and more expensive – but the expense is offset by cheap credit provided by sellers who are eager to encourage buyers to buy."[24]

Controversy[]

The view that higher education is a bubble is highly controversial. Most economists do not think that returns to a college education are falling but instead believe that the benefits far outweigh the costs.[8][9][10][26] Yet, the returns for marginal students or students in certain majors, especially at costly private universities, may not justify the investment.[27] It has been suggested that the returns to education should be compared to the returns to other forms of investment such as the stock market, bonds, real estate, and private equity. A higher return would suggest underinvestment in higher education, but lower returns would suggest a bubble.[28] Studies have typically found a causal relationship between growth and education, although the quality and type of education matters, and not just the number of years of schooling.[29][30][31][32]

In a financial bubble, assets like houses are sometimes purchased with a view to reselling at a higher price, and this can produce rapidly escalating prices as people speculate on future prices. An end to the spiral can provoke abrupt selling of the assets, resulting in an abrupt collapse in price – the bursting of the bubble. Because the asset acquired through college attendance – a higher education – cannot be sold but only rented through wages, there is no similar mechanism that would cause an abrupt collapse in the value of existing degrees. For this reason, this analogy could be misleading. However, one rebuttal to the claims that a bubble analogy is misleading is the observation that the 'bursting' of the bubble are the negative effects on students who incur student debt, for example, as the American Association of State Colleges and Universities reports that "Students are deeper in debt today than ever before.... The trend of heavy debt burdens threatens to limit access to higher education, particularly for low-income and first-generation students, who tend to carry the heaviest debt burden. Federal student aid policy has steadily put resources into student loan programs rather than need-based grants, a trend that straps future generations with high debt burdens. Even students who receive federal grant aid are finding it more difficult to pay for college."[33]

However, the data actually show that notwithstanding a slight increase in 2008–2009, student loan default rates have declined since the mid-1980s and 1990s.[13][14] During both periods of growth and recession, those with college degrees are much less likely than those without to be unemployed, even though they earn higher wages.[15]

Ohio University economist Richard Vedder has written in The Wall Street Journal that:

A key measure of the benefits of a degree is the college graduate's earning potential – and on this score, their advantage over high-school graduates is deteriorating. Since 2006, the gap between what the median college graduate earned compared with the median high-school graduate has narrowed by $1,387 for men over 25 working full time, a 5% fall. Women in the same category have fared worse, losing 7% of their income advantage ($1,496). A college degree's declining value is even more pronounced for younger Americans. According to data collected by the College Board, for those in the 25–34 age range, the differential between college graduate and high school graduate earnings fell 11% for men, to $18,303 from $20,623. The decline for women was an extraordinary 19.7%, to $14,868 from $18,525. Meanwhile, the cost of college has increased 16.5% in 2012 dollars since 2006, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics' higher education tuition-fee index.[34]

Alternatives to bubble theory[]

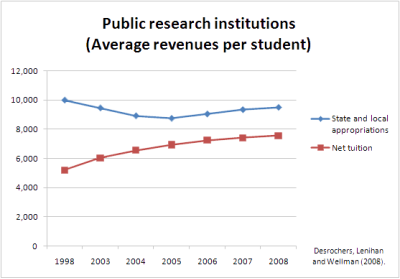

A different explanation for rising tuition is the reduction of state and federal appropriations to colleges, making them more reliant on student tuition. Thus, it is not a bubble but a form of shifting costs away from state and federal funding over to students.[35] This has mostly applied to public universities which in 2011 for the first time have taken in more in tuition than in state funding[35] and had the greatest increases in tuition.[25] Implied from this shift away from public funding to tuition is privatization, although The New York Times reported that such claims are exaggerated.[35]

A second theory claims that as a result of federal law that severely restricts the ability of students to discharge their federally guaranteed student loans in bankruptcy, lenders and colleges know that students are on the hook for any amount that they borrow, including late fees and interest (which can be capitalized and increase the principal loan amount), thus removing the incentive to only provide students loans that the students can be reasonably expected to repay.[36][37] As evidence for this theory, it has been suggested that returning bankruptcy protections (and other standard consumer protections) to student loans would cause lenders to be more cautious, thereby causing a sharp decline in the availability of student loans, which, in turn, would decrease the influx of dollars to colleges and universities, who, in turn, would have to sharply decrease tuition to match the lower availability of funds.[38]

Economic and social commentator Gary North has remarked at LewRockwell.com, "To speak of college as a bubble is silly. A bubble does not pop until months or years after the funding ceases. There is no indication that the funding for college education will cease."[17]

Azar Nafisi, Johns Hopkins University professor and bestselling author of Reading Lolita in Tehran, has stated on the PBS NewsHour that a purely economic analysis of a higher education bubble is incomplete:

Universities become sort of like canaries in the mine for a culture. They become the sort of standard of where culture is going. The dynamism, the originality of these entrepreneurial experiences, the fact that society allows people to be original, to take risks, all of it comes from a passionate love of knowledge. And universities represent all the different areas and fields within a society. And the students and faculty come from all these fields. This is a community that represents the best that a society has to offer. And there was a mention of our universities being the best in the world.[39]

Recommendations[]

Commentators have recommended certain policies to varying degrees of controversy:

- State and federal governments should increase appropriations, grants, and contracts to colleges and universities.[40][41]

- Federal, state, and local governments should reduce the regulatory burden on colleges and universities.[42]

- Minimize the risk of investment in higher education through loan forgiveness or insurance programs.[43] The federal government should enact partial or total loan forgiveness for student loans.[44][45][46]

- Colleges and universities should look for ways to reduce costs without reducing quality.[47]

- Federal lawmakers should return standard consumer protections (truth in lending, bankruptcy proceedings, statutes of limitations, etc.) to student loans which were removed by the passage of the Bankruptcy Reform Act of 1994 (P.L. 103-394, enacted October 22, 1994), which amended the FFELP (Federal Family Education Loan Program).[48][49][50]

See also[]

- College admissions in the United States

- College tuition in the United States

- Credentialism and educational inflation

- EdFund

- Free education

- Higher Education Price Index

- Higher education in the United States

- Tertiary education

- Private university

- Student debt

- Student loans in the United States

- Tuition payments

- Tuition freeze

References[]

- ^ Archibald, Robert B.; Feldman, David (David H.) (2006). "State Higher Education Spending and the Tax Revolt" (PDF). The Journal of Higher Education. 77 (4): 618–644. doi:10.1353/jhe.2006.0029. ISSN 1538-4640. S2CID 154906564.

- ^ Barshay, Jill (4 August 2014). "Reflections on the underemployment of college graduates". Hechniger Report. Teachers College at Columbia University. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ^ Coates, Ken; Morrison, Bill (2016), Dream Factories: Why Universities Won't Solve the Youth Jobs Crisis, Toronto: Dundurn Press, p. 232, ISBN 978-1459733770

- ^ "U.S. Republican budget cuts social spending, boosts military". Reuters. 2015-03-17. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ^ "Should the U.S. cut spending on education (yes) or the military (no)?". www.debate.org. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ^ "Gov. Sam Brownback cuts higher education as Kansas tax receipts fall $53 million short". kansascity. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ^ "Changing Priorities: State Criminal Justice Reforms and Investments in Education | Center on Budget and Policy Priorities". www.cbpp.org. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Michael Simkovic, Risk-Based Student Loans (2012)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Thomas Lemieux, Postsecondary Education And Increasing Wage Inequality, 96 AM. ECON. REVIEW 195 (2006)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Sandy Baum and Michael McPherson, Job-Skill Trends and the College-Wage Premium, Chronicle of Higher Education, Sept. 21, 2010

- ^ Singletary, Michelle (11 January 2020). "Is college still worth it? Read this study". The Washington Post. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ William R. Emmons; Ana H. Kent; Lowell R. Ricketts (January 7, 2019). "Is College Still Worth It? The New Calculus of Falling Returns" (PDF).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pope, Justin (12 September 2011). "Student loan default rates jump". Phys.org. Science X network.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kirkham, Chris (September 12, 2011). "Led By For-Profit Colleges, Student Loan Defaults At Highest Level In A Decade". Huffington Post.

- ^ Jump up to: a b U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Education Pays

- ^ McKinsey Global Institute, An Economy that Works: Job Creation and America's Future, June 2011

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gary North (May 2, 2011). "College: Why It Is Not a Bubble". LewRockwell.com. Retrieved November 15, 2011.

- ^ Bennett, William J. (Feb 18, 1987). "Our Greedy Colleges". The New York Times.

- ^ "How U.S. News Calculates the College Rankings". US News and World Report. 2010. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ "Estimating the Payoff to Attending a More Selective College: An Application of Selection on Observables and Unobservables" (PDF). Dale, S. B. and Krueger, A. B., NBER. 1999. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2011-05-03. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Ley, Katharina; Keppo, Jussi (2011). "The Credits that Count: How Credit Growth and Financial Aid Affect College Tuition and Fees". Ley, K. and Keppo, J., SSRN. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1766549. S2CID 154146898. SSRN 1766549. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Eichler, Alexander (August 30, 2011). "Hiring Is Up For The Class Of 2011, But Previous Classes Still Struggle". Huffington Post.

- ^ Johnson, Lacey (17 November 2011). "Job Outlook for College Graduates Is Slowly Improving". The Chronicle of Higher Education.

- ^ Reynolds, Glenn H. (2012). The higher education bubble. New York: Encounter Books. p. 1. ISBN 978-1594036651.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Trends in College Spending 1998–2008 Archived 2013-08-08 at the Wayback Machine" (PDF) Delta Cost Project

- ^ Claudia Goldin, Lawrence F. Katz (2008). The Race Between Education and Technology. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- ^ Caplan, Bryan (2018). The Case Against Education: Why the Education System Is a Waste of Time and Money. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691174655.

- ^ Simkovic, Michael (2015). "The Knowledge Tax". University of Chicago Law Review. SSRN 2551567.

- ^ Benhabib, Jess; Spiegel, Mark M. (October 1994). "The role of human capital in economic development evidence from aggregate cross-country data". Journal of Monetary Economics. 34 (2): 143–173. doi:10.1016/0304-3932(94)90047-7.

- ^ Pritchett, Lant. "Where has all the education gone?" (PDF). Harvard.edu. World Bank & Kennedy School of Government (2000).

- ^ Hanushek, Eric A.; Woessmann, Ludger (December 2010). "How Much Do Educational Outcomes Matter in OECD Countries?" (PDF). IZA Discussion Paper No. 5401.

- ^ Holmes, Craig (May 2013). "Has the Expansion of Higher Education Led to Greater Economic Growth?". National Institute Economic Review. 224 (1): R29–R47. doi:10.1177/002795011322400103.

- ^ Hillman, Nick (2006). "Student Debt Burden, Volume 3, Number 8, August 2006" (PDF). American Association of State Colleges and Universities. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-11. Retrieved 2011-07-13.

- ^ Vedder, Richard; Denhart, Christopher (8 January 2014), How the College Bubble Will Pop, American Enterprise Institute, retrieved 12 July 2014

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Public Universities Relying More on Tuition Than State Money", The New York Times 2011/01/24

- ^ Quinn, Jane (24 September 2010). "Student Loans: Time to Reform the Law That Treats Debtors Like Crooks". CBS News. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ Weissman, Jordan (16 April 2015). "How the Bush Administration Pointlessly Screwed Over Student Borrowers". Slate. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ "Why College Prices Keep Rising". Forbes.com. 2012.

- ^ "Is a College Diploma Worth the Soaring Student Debt?". PBS NewsHour. May 27, 2011. Retrieved November 16, 2011.

- ^ "Affordable Higher Education: Student Debt". U.S. PIRG. 2011. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^ "Fight to Protect Students and Taxpayers Moves to Senate! - House Voted to Slash Pell Grants and Block Gainful Employment Rule". ProjectOnStudentDebt.org. 2011.

- ^ Kantrowitz, Mark (2002). "Research Report: Causes of faster-than-inflation increases in college tuition" (PDF). FinAid.

- ^ Brooks, John (2016). "Income-Driven Repayment and the Public Financing of Higher Education". Georgetown Law Journal.

- ^ Applebaum, Robert (2009). "The Proposal". ForgiveStudentLoanDebt.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-28. Retrieved 2011-07-12.

- ^ "Real Loan Forgiveness". ProjectOnStudentDebt.org. 2011.

- ^ "Take Action for Real Loan Forgiveness!". ProjectOnStudentDebt.org. 2009.

- ^ Kantrowitz, Mark (2002). "Research Report: Causes of faster-than-inflation increases in college tuition" (PDF). FinAid.

- ^ Collinge, Alan (2011). "Private Student Loan Bankruptcy Bill ... The 4th Attempt". StudentLoanJustice.org. Archived from the original on 2011-07-01.

- ^ "Bankruptcy Relief for Private Student Loan Borrowers Advances". ProjectOnStudentDebt.org. 2010.

- ^ Collinge, Alan (2012). "Why College Prices Keep Rising". Forbes.

Further reading[]

- Angulo, A. (2016). Diploma Mills: How For-profit Colleges Stiffed Students, Taxpayers, and the American Dream. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Armstrong, E. and Hamilton, L. (2015). Paying for the Party: How College Maintains Inequality. Harvard University Press.

- Bennett, W. and Wilezol, D. (2013). Is College Worth It?: A Former United States Secretary of Education and a Liberal Arts Graduate Expose the Broken Promise of Higher Education. Thomas Nelson.

- Best, J. and Best, E. (2014) The Student Loan Mess: How Good Intentions Created a Trillion-Dollar Problem. Atkinson Family Foundation.

- Caplan, B. (2018). The Case Against Education: Why the Education System Is a Waste of Time and Money. Princeton University Press.

- Cappelli, P. (2015). Will College Pay Off?: A Guide to the Most Important Financial Decision You'll Ever Make. Public Affairs.

- Golden, D. (2006). The Price of Admission: How America’s Ruling Class Buys its Way into Elite Colleges — and Who Gets Left Outside the Gates.

- Goldrick-Rab, S. (2016). Paying the Price: College Costs, Financial Aid, and the Betrayal of the American Dream.

- Reynolds, G. (2012). The Higher Education Bubble. Encounter Books.

- Universities and colleges in the United States

- Education finance in the United States

- Higher education in the United States

- Education economics

- Economic bubbles