Hinton St Mary Mosaic

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2018) |

| The Hinton St Mary Mosaic | |

|---|---|

| |

| Material | Ceramic |

| Created | early 4th century |

| Period/culture | Romano-British (Christian) |

| Place | Hinton St Mary villa, Dorset |

| Present location | G49/wall, British Museum, London |

| Registration | 1965,0409.1 |

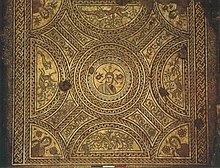

The Hinton St Mary Mosaic is a large, almost complete Roman mosaic discovered at Hinton St Mary, Dorset, England. It appears to feature a portrait bust of Jesus Christ as its central motif. The mosaic was chosen as Object 44 in the BBC Radio 4 programme A History of the World in 100 Objects, presented by British Museum director Neil MacGregor.

The mosaic covered two rooms, joined by a small decorated threshold. It is largely red, yellow and cream in colouring. On stylistic grounds it has been dated to the 4th century and is attributed to the mosaic workshop of Durnovaria (modern Dorchester). It is currently in storage at the British Museum, although the central medallion is on display there.

Christian panel[]

The panel in the larger room is 17 by 15 feet (5.2 by 4.6 m). A central circle surrounds a portrait bust of a man in a white pallium standing before a Christian chi-rho symbol flanked by two pomegranates. He is generally identified as Christ, although the Emperor Constantine I has also been suggested[1] despite the absence of any insignia or identifiers pointing to a particular emperor other than the chi-rho. On each side of this are four lunettes, each featuring conventional forest and hunting vignettes, mostly of a dog and a deer. In the corners are four quarter circles containing portrait busts, either representing the winds or the seasons.[2]

Pagan panel[]

The panel in the smaller room is 16+1⁄2 by 8 feet (5.0 by 2.4 m). It consists of a central circle containing an image of characters from Roman mythology, Bellerophon killing the Chimera. This has been interpreted in a more Christian context as representing good defeating evil. Flanking this are two rectangular panels again featuring dogs hunting deer.

Context[]

The mosaic was discovered on 12 September 1963 by the local blacksmith, Walter John White.[3] It was cleared by the Dorset County Museum[3] and lifted for preservation by the British Museum,[4] although none of the rest of the building has been examined. It is generally assumed to have been a villa. The layout of the mosaic room certainly resembles a Roman triclinium, or dining room. However, it might easily be a church or other Christian complex. There were no finds dated earlier than c. 270.

Destruction[]

In 2000 a new roof was erected by architects Foster and Partners to cover the previously open courtyard of the British Museum.[5] As part of this major building work it was decided that the Hinton St Mary mosaic should be moved.

The previously intact mosaic,[6] which was fixed to the museum floor, was levered up and broken into pieces by Museum staff in 1997. Chris Smith, the former Director of ‘Art Pavements’ which moved the mosaic from Dorset, was described as “outraged at what he saw as an act of vandalism and stated that it was completely unnecessary as moving the mosaic was quite feasible without damage.”[7]

The pieces are now stored in boxes in the museum vaults with only the central Christian portrait on display in the Gallery.[8]

The Association for the Study and Preservation of Roman Mosaics protested at the destruction and decision to only display part of the mosaic. They launched a petition stating that “the mosaic possibly contains the only known representation of Christ in an ancient pavement, it is of unique importance not just in Britain but in the context of the Roman Empire as a whole, and merits being displayed in its entirety. It is insufficient to show the central roundel in isolation, however important. The full meaning of the pavement can be appreciated only if the whole of it is visible, including the accompanying heads and figure scenes”.[9]

The Association for the Study and Preservation of Roman Mosaics also produced a factsheet about the entire mosaic.[10]

Partial return to Dorset?[]

On 2 August 2019, Hinton St Mary villagers and the Chair of the Dorset Unitary Authority[11] were told at a closed-door meeting with the British Museum that the mosaic would be partially returned to the Dorset County Museum. However, the head of Christ would not be returned, as the original would be “loaned to museums worldwide”. A replica would be given to the Dorset County Museum.[12][13]

No answer was given to one attendee’s question that: “Given that she [a British Museum curator] boasted the fact that the replicas they made were indistinguishable from the originals, surely it would make more sense to send the replica around the world and keep the original safe in Dorset?”[14]

It is not clear whether the complete mosaic[15][16] or only a part of it will be displayed in Dorset County Museum.

The Sturminster Newton Museum (around 2 miles or 3 kilometres south of Hinton St Mary) has a display about the mosaic, its finding and planned return, and the local area in Roman times.[17]

References[]

- ^ Moorhead, Sam; Stuttard, David (2012). The Romans who Shaped Britain. Thames & Hudson. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-500-25189-8.

- ^ "ASPROM factsheet: The Hinton St Mary mosaic in the British Museum, 2013". The Association for the Study and Preservation of Roman Mosaics. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ a b Toynbee 1964, p. 7.

- ^ Painter 1967, pp. 21–22.

- ^ www.fosterandpartners.com, Foster + Partners /. "Great Court at the British Museum | Foster + Partners". www.fosterandpartners.com. Retrieved 2019-12-06.

- ^ "Object: The Hinton St Mary Mosaic". Archived copy on Archive.is of original British Museum webpage. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "The tragic destruction of the Hinton St Mary Mosaic". Gary Drostle. 2015-07-11. Retrieved 2019-12-06.

- ^ "The tragic destruction of the Hinton St Mary Mosaic". Gary Drostle. 2015-07-11. Retrieved 2019-12-06.

- ^ "ASPROM News archive, June 2010: Please sign the Hinton St Mary petition!". Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "ASPROM factsheet: The Hinton St Mary mosaic in the British Museum, 2013". The Association for the Study and Preservation of Roman Mosaics. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "Mosaic Update". The Arts Society Blackmore Vale. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "The Mosaic, Hinton St. Mary village newsletter, September 2019" (PDF). Hinton St Mary – an idyllic Dorset village. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "Mosaic Update". The Arts Society Blackmore Vale. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "The Mosaic, Hinton St. Mary village newsletter, September 2019" (PDF). Hinton St Mary – an idyllic Dorset village. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "Object: The Hinton St Mary Mosaic". Archived copy on Archive.is of original British Museum webpage. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "ASPROM factsheet: The Hinton St Mary mosaic in the British Museum, 2013". The Association for the Study and Preservation of Roman Mosaics. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "The Museum, SNHT". Sturminster Newton Heritage Trust. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

Further reading[]

- Neal, D. S. (1981). Roman Mosaics in Britain.

- Painter, Kenneth (Autumn 1967). "The Roman Site at Hinton St. Mary, Dorset". The British Museum Quarterly. British Museum. XXXII (1–2): 15–31. doi:10.2307/4422986. JSTOR 4422986.

- Smith, D. J. (1969). 'The Mosaic Pavements' in Rivet, A. L. F. The Roman Villa in Britain.

- Toynbee, Jocelyn Mary Catherine (1964). "A New Roman Mosaic Pavement Found in Dorset". The Journal of Roman Studies. Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. LIV (1–2): 7–14. doi:10.2307/298645. JSTOR 298645.

External links[]

- British Museum page

- BBC A History of the World in 100 Objects page

- The Association for the Study and Preservation of Roman Mosaics

- Christianity in Roman Britain

- Romano-British objects in the British Museum

- History of Dorset

- Roman sites in Dorset

- Roman religious sites in England

- Christian buildings and structures in the Roman Empire

- Archaeological sites in Dorset

- Roman mosaics