History of Samoa

The Samoan Islands were first settled some 3,500 years ago as part of the Austronesian expansion. Both Samoa's early history and its more recent history are strongly connected to the histories of Tonga and Fiji, nearby islands with which Samoa has long had genealogical links as well as shared cultural traditions.

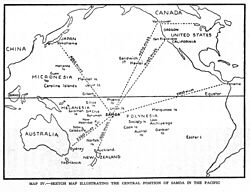

European explorers first reached the Samoan islands in the early 18th century. In 1768, Louis-Antoine de Bougainville named them the Navigator Islands. The United States Exploring Expedition (1838–42), led by Charles Wilkes, reached Samoa in 1839. In 1855, J.C. Godeffroy & Sohn expanded its trading business into the Samoan archipelago. The first Samoan Civil War (1886-1894) led to the so-called Samoan crisis, a struggle between Western powers for control of the area. This in turn led to the Second Samoan Civil War (1898-1899), which was resolved by the Tripartite Convention, in which the United States, Great Britain and Germany agreed to partition the islands into German Samoa and American Samoa.

After World War I, New Zealand took over the administration of what had been German Samoa, and the area was renamed the Western Samoa Trust Territory. This area became independent in 1962 and was renamed Samoa. American Samoa remains an unincorporated territory of the United States.

Early history[]

Archeologists estimate that the earliest human settlement of the Samoan archipelago was around 2900–3500 years before the present (1500-900 BCE).[1] This estimate is based on dating the ancient Lapita pottery shards that are found throughout the islands. The oldest shards found so far have been in Mulifanua and in Sasoa'a, Falefa.[1] The oldest archaeological evidence found on the islands of Polynesia, Samoa and Tonga all date from around that same period, suggesting that the first settlement occurred around the same time in the region as a whole. Little is known about human activity in the islands between 750 BC and 1000 AD, though this may have been a period of mass migrations that led to the settlement of present-day Polynesia. Mysteriously, during this period, the making of pottery appears to have suddenly stopped. The Samoan peoples have no oral tradition that purports to explain this. Some archaeologists have suggested that Polynesia lacked pottery-making materials, and that most of the pottery used during the migration period in Polynesia was imported rather than sourced or crafted locally.

Samoa's early history is interwoven with the history of certain chiefdoms of Fiji and of the kingdom of Tonga. The oral history of Samoa preserves the memories of many battles fought between Samoa and neighboring islands. Intermarriage between Tongan and Fijian royalty and Samoan nobility helped build close relationships between these island nations that still exist today. These royal blood ties are routinely acknowledged at special events and cultural gatherings. According to Samoan folklore, two maidens from Fiji brought to Samoa the tools that were necessary to engage in the art of tatau (in English, tattoo), and this is the origin of the traditional Samoan malofie (also known as pe'a for men and as malu for women).

The dominant cultural traditions of Samoa, known as the fa'asamoa, originated with the warrior queen Nafanua. Her rule instituted the fa'amatai: decentralized family, village, and regional chiefly systems. Her niece, Salamasina, continued this system, and their era is considered to be a golden age of Samoan cultural traditions.

Linguistically, the Samoan language belongs to the Polynesian sub-branch of the Austronesian language family, which is thought by linguists to have originated in Taiwan.

According to oral tradition, Samoa and Polynesian share a common ancestor: Tagaloa.[2] The earliest history of Samoa concerns a political center in the easternmost Samoan islands of Manu'a, under the rule of the Tui Manu'a. In the Cook Islands to the east, the tradition is that Karika, or Tui Manu'a 'Ali'a, came to the Cook Islands from Manu'a; suggesting that the rest of Polynesia was settled from Manu'a and Samoa.

After European contact[]

18th century[]

Contact with Europeans began in the early 18th century but did not intensify until the arrival of the British missionaries. In 1722, Dutchman Jacob Roggeveen was the first European to see the islands. This visit was followed by the French explorer Louis-Antoine de Bougainville (1729–1811), the man who named them the Navigator Islands in 1768. In 1787 Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse visited Samoa, where at Tutuila Island, in what is now American Samoa, there was a conflict leading to deaths on both sides, including the deaths of twelve Frenchmen.

19th century[]

European and Tahitian and Cook Islander Missionaries and traders, led by John Williams (missionary) began arriving around 1830. Coming via Tahiti, they were known in Samoa as the Lotu Taiti. The Rev. John Williams was helped by the Ali'i Malietoa Vainu'upo to establish the Lotu Taiti, which became the Christian Congregational Church of Samoa.

The United States Exploring Expedition (1838–42) under Charles Wilkes reached Samoa in 1839 and appointed an Englishman, John C. Williams, son of the missionary, as acting U.S. consul.[3] However this appointment was never confirmed by the U.S. State Department; John C. Williams was merely recognized as "Commercial Agent of the United States".[3] A British consul was already residing at Apia.

In 1855 J.C. Godeffroy & Sohn expanded its trading business into the Samoan Islands, which were then known as the Navigator Islands. During the second half of the 19th century German influence in Samoa expanded with large plantation operations being introduced for coconut, cacao and hevea rubber cultivation, especially on the island of 'Upolu where German firms monopolized copra and cocoa bean processing. British business enterprises, harbour rights, and consulate office were the basis on which Britain had cause to intervene in Samoa. The United States began operations at the harbor of Pago Pago on Tutuila in 1877 and formed alliances with local native chieftains, most conspicuously on the islands of Tutuila and Manu'a (which were later formally annexed as American Samoa).

In the 1880s Great Britain, Germany and the United States all claimed parts of the kingdom of Samoa, and established trade posts. The rivalry between these powers exacerbated tensions between the indigenous factions which were all jockeying for complete political authority. The islands were divided among the three powers in the 1890s, and between the United States and Germany in 1899.[4]

The First Samoan Civil War and the Samoan crisis[]

The First Samoan Civil War was fought roughly between 1886 and 1894, primarily between rival Samoan factions, although the rival powers intervened on several occasions with military forces. There followed an eight-year civil war, where each of the three powers supplied arms, training, and in some cases, combat troops to the warring Samoan parties.[5] The Samoan crisis came to a critical juncture in March 1889 when all three Western contenders sent warships into , and a larger-scale war seemed imminent, until a massive storm on 15 March 1889 damaged or destroyed the warships, ending the military conflict.[6]

Robert Louis Stevenson arrived in Samoa in 1889 and built a house at Vailima. He quickly became passionately involved in the attendant political machinations. His influence spread to the Samoans, who consulted him for advice, and he soon became involved in local politics. These involved the three great powers battling for control of Samoa - America, Germany and Britain - and the indigenous factions which were all jockeying for complete political authority.. He was convinced that the European officials appointed to rule the Samoans were incompetent, and after many futile attempts to resolve the matter, he published A Footnote to History. The book covers the period from 1882 to 1892.[6] This was such a stinging protest against existing conditions that it resulted in the recall of two officials, and Stevenson feared for a time it would result in his own deportation.[7]

The Second Samoan Civil War and the Siege of Apia[]

The Second Samoan Civil War reached a head in 1898 when Germany, Great Britain and the United States disputed over who should control the Samoan Islands.

The Battle of Apia occurred in March 1899. Samoan forces loyal to Prince Tanu were besieged by a larger force of Samoan rebels loyal to powerful chief Mata'afa Iosefo. Supporting Prince Tanu were landing parties from four British and American warships. Over several days of fighting, the Samoan rebels were defeated.[8]

American and British warships shelled Apia on 15 March 1899; including the USS Philadelphia. Following the initial defeat at Apia, Mata'afa's rebels defeated a combined American, British and Tanu allied force at Vailele on 1 April 1899, with the allies in retreat.[9] According to a war correspondent associated with the Auckland Star newspaper, the aftermath saw Mata'afa's warriors leaving American and British corpses on the field being severed of their heads.[10] Germany, Britain and the United States quickly resolved to end the hostilities by partitioning the island chain at the Tripartite Convention of 1899.[3] With Tanu and his American and British allies' inability to defeat him in war, the Tripartite resulted in Mata'afa being promoted to Ali'i Si'i, the high chief of Samoa.[9]

Division of islands[]

The Samoa Tripartite Convention of 1899, a joint commission of three members composed of Bartlett Tripp for the United States, C. N. E. Eliot, C.B. for Great Britain, and Freiherr Speck von Sternburg for Germany, agreed to divide the islands.

The Tripartite Convention gave control of the islands west of 171 degrees west longitude to Germany, (later known as Western Samoa), containing Upolu and Savaii (the current Samoa) and other adjoining islands. These islands became known as German Samoa. The United States was given control the eastern islands of Tutuila and Manu'a, (present-day American Samoa).[3] In exchange for Britain ceding claims in Samoa, Germany transferred their protectorates in the North Solomon Islands and other territories in West Africa. It does not appear that any Samoans were consulted about the partition and the monarchy was also abolished.

From 1908, with the establishment of the Mau movement ("opinion movement"), Western Samoans began to assert their claim to independence. The Mau movement began in 1908 with the 'Mau a Pule' resistance on Savai'i, led by orator chief Lauaki Namulau'ulu Mamoe. Lauaki and Mau a Pule chiefs, wives and children were exiled to Saipan in 1909. Many died in exile.[2]

World War I broke out in August 1914, and soon after, New Zealand sent an expeditionary force to seize and occupy German Samoa. Although Germany refused to officially surrender the islands, no resistance was offered and the occupation took place without any fighting. New Zealand continued the occupation of Western Samoa throughout World War I. Under the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, Germany relinquished its claims to the islands.

New Zealand rule[]

In November 1918, the Spanish flu strongly hit the territory. 90% of the 38,302 native inhabitants were infected and 20% died. The American Samoa population was largely spared this devastation, due to vigorous efforts of its governor, John Martin Poyer. This led to some Samoan citizens petitioning in January 1919 for transfer to U.S. administration, or at least away from the New Zealand administration. The petition was recalled a few days later.[11]

New Zealand administered Western Samoa, or Samoa i Sisifo in the Samoan language, first as a League of Nations Mandate and then as a United Nations Trust Territory. The Mau movement gained momentum with Samoa's royal leaders becoming more visible in supporting the movement but opposing violence. On 28 December 1929 Tupua Tamasese was shot along with eleven others during an otherwise peaceful demonstration in Apia. Tupua Tamasese died the following day; his final words included a plea that no more blood be shed. The leaders of the Mau and other Samoan critics of the administration of Samoa were sent into exile in New Zealand, including Olaf Frederick Nelson.[12][13]

Independence[]

Samoa received its independence from New Zealand on 1 January 1962 and adopted the name Western Samoa.[14] Samoa's first prime minister following independence was paramount chief Fiame Mata'afa Faumuina Mulinu'u II.[15][16] Later that year a treaty of friendship was signed with New Zealand, under which New Zealand agreed to assist Western Samoa in foreign policy if desired.[17] Samoa i Sisifo was the first Polynesian people to be recognized as a sovereign nation in the 20th century. Samoa became one of the Member states of the Commonwealth of Nations on 28 August 1970. In 1977, Queen Elizabeth II visited Samoa during her tour of the Commonwealth.

A conflict briefly emerged between Samoa and American Samoa following Samoa's decision to drop the adjective "Western" from its name. The change was made by an act of the Legislative Assembly of Western Samoa adopted on 4 July 1997.[18] The step caused "surprise and uproar" in neighboring American Samoa, as for some American Samoans the change of name implied a claim to be the "real" Samoa and implied that American Samoa was just an American appendix.[19] Some in the American territory said it implied that there was only one Samoa. Two members of American Samoa's legislature traveled to Apia in September 1997 to meet with Samoan head of State Malietoa Tanumafili II, and lobbied to have the name change reversed in order to maintain peace and good relations.[19] An American Samoan petition to the United Nations for a ban on Samoa's using the name Samoa was seriously discussed and ten American Samoan representatives sponsored an unsuccessful bill aimed at preventing American Samoa from recognizing independent Samoa's new name.[19] The proposed American Samoan bill was criticized by independent Samoa's Prime Minister Tofilau Eti Alesana who called the bill "rash and irresponsible".[19]

In 2002, New Zealand's prime minister Helen Clark formally apologized for two incidents during the period of New Zealand's administration: a failure in 1918 to quarantine the SS Talune, which carried the 'Spanish 'flu' to Samoa, leading to an epidemic which devastated the Samoan population, and the shooting of leaders of the non-violent Mau movement during a ceremonial procession in 1929.

In 2007, Samoa's first head of state, His Highness Malietoa Tanumafili II, died at age 95. He held this title jointly with Tupua Tamasese Lealofi until the latter's death in 1963. Malietoa Tanumafili II was Samoa's Head of State for 45 years. He was the son of Malietoa Tanumafili I, who was the last Samoan king recognized by Europe and the Western World.

Samoa's current head of state is His Highness Tuimalealiifano Va'aletoa Sualauvi II, who was anointed the head of state title with the unanimous endorsement of Samoa's Parliament, a symbol of traditional Samoan protocol in alignment with Samoan decision-making stressing the importance of consensus in the 21st century.

In May 2021, Fiame Naomi Mataʻafa became Samoa's first female prime minister. Fiame's FAST party won narrowly the election, ending the rule of long-term Prime Minister Tuilaepa Sailele Malielegaoi.[20] On 24 May 2021, she was sworn in as the new prime minister.[21]

Calendar usage in Samoa[]

As European traders began commercial (and later domination) activities in the Samoan Islands, they imposed their datekeeping system on their transactions. Thus by the 19th century, Samoan calendars were aligned with those of the other Asiatic countries to the west and south. However, in 1892, American traders convinced the king to alter the country's dating system to align with the United States; thus the country lived through 4 July 1892, twice. But 119 years later, the economic geography of the island had changed, and most business was being done with Australia and New Zealand. To make the jump back to the Asian date Samoa and Tokelau skipped 30 December 2011.[22]

See also[]

- American Samoa

- History of Oceania

- List of Prime Ministers of Samoa

- Malietoa - state dynasty and chiefly title

- Politics of Samoa

References[]

- ^ a b Petchey, Fion J (2001). "Radiocarbon Determinations from the Mulifanua Lapita Site, Upolu, Western Samoa". Radiocarbon. 43 (1): 63–68. doi:10.1017/S0033822200031635.

- ^ a b Tuvale, Te'o. "An account of Samoan history up to 1918: Chapters I-IV". Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- ^ a b c d Ryden, George Herbert. The Foreign Policy of the United States in Relation to Samoa. (Yale University Press, 1928), p. 574; the Tripartite Convention (United States, Germany, Great Britain) was signed at Washington on 2 December 1899 with ratifications exchanged on 16 February 1900.

- ^ Paul M. Kennedy, The Samoan Tangle: A Study in Anglo-German-American Relations 1878–1900 (University of Queensland Press, 2013).

- ^ Spencer Tucker, ed. (2009). The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. pp. 569–70. ISBN 9781851099511.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ a b Stevenson, Robert Louis. A Footnote to History: Eight Years of Trouble in Samoa. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 978-1-4264-0754-3.

- ^ Letter to Sidney Colvin, 17 April 1893, Vailima Letters, Chapter XXVIII

- ^ Mains, P. John; McCarty, Louis Philippe (1906). The Statistician and Economist: Volume 23. p. 249

- ^ a b Kohn, George C. (1986). Dictionary of wars, Third Edition. Facts on File Inc, factsonfile.com. pp. 479–480. ISBN 978-0-8160-6577-6.

- ^ [1] Papers Past (website)

- ^ Mary Boyd (1968). "The Military Administration of Western Samoa, 1914-1919" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of History. 2 (2): 163. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ "Western Samoa – A Continuing Disappointment". II(10) Pacific Islands Monthly. 19 May 1932. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ "Pig-Headed New Zealand and Stubborn Samoa". III(3) Pacific Islands Monthly. 19 October 1932. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage (19 July 2010). "Towards independence - NZ in Samoa". nzhistory.net.nz. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ^ Mata'afa, friend to all, who led Samoa 'long and loyally' Pacific Islands Monthly, July 1975, p7

- ^ "Western Samoa SMOOTH PROGRESS TO INDEPENDENCE". The Press. 30 December 1961. p. 10. Retrieved 28 September 2021 – via Papers Past.

- ^ Brij V Lal (22 September 2006). "'Pacific Island talks': Commonwealth Office notes on four-power talks in Washington". British Documents on the End of Empire Project Series B Volume 10: Fiji. University of London: Institute of Commonwealth Studies. p. 305. ISBN 9780112905899.

- ^ Constitution Amendment Act (No. 2) 1997 (No. 15)

- ^ a b c d Migration happens: reasons, effects and opportunities of Migration, Katarina Ferro, Margot Wallner and Richard Bedford, 2006. p. 72

- ^ "Samoa set to appoint first female prime minister". Reuters. 17 May 2021.

- ^ "Pacific island swears in its first female PM in a tent after she is locked out of Parliament".

- ^ [2] slate.com, The Philippines Skipped A Day

- Eustis, Nelson. 1979. Aggie Grey of Samoa. Hobby Investments, Adelaide, South Australia. 2nd printing, 1980. ISBN 0-9595609-0-4

Further reading[]

- Kennedy, P. M. "Bismarck's Imperialism: The Case of Samoa, 1880-1890." Historical Journal 15, no. 2 (1972): 261–83. online.

- Kennedy, Paul M. The Samoan Tangle: A Study in Anglo-German-American Relations 1878–1900 (University of Queensland Press, 2013).

- Ryden, George Herbert. The Foreign Policy of the United States in Relation to Samoa (Yale University Press, 1928).

External links[]

- [3] Samoa, A Hundred Years Ago And Long Before, George Turner (1884), an eText available from Project Gutenberg

- History of Samoa

- New Zealand–Pacific relations

- History of the Samoan Islands