History of Sarasota, Florida

hideThis article has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| History of Florida |

|---|

|

|

|

The area known today as Sarasota, Florida first appeared on a sheepskin Spanish map from 1763 with the word "Zarazote" over present day Sarasota and Bradenton.[1] The municipal government of Sarasota was established when it was incorporated as a town in 1902.[2]

Early history[]

Prehistory[]

Fifteen thousand years ago, when humans first settled in Florida, the shoreline of the Gulf of Mexico was one hundred miles farther to the west. In this era, hunting and gathering was the primary means of subsistence. This was only possible in areas where water sources existed for hunter and prey alike. Deep springs and catchment basins, such as Warm Mineral Springs, were close enough to the Sarasota area to provide campsites, but too far away for permanent settlements.

As the Pleistocene glaciers slowly melted, a more temperate climate began to advance northward. Sea levels began rising; they ultimately rose another 350 feet (110 m), resulting in the Florida shoreline of today, which provided attractive locations for human settlements.

Archaeological research in Sarasota documents more than ten thousand years of seasonal occupation by native peoples. For five thousand years while the current sea level existed, fishing in Sarasota Bay was the primary source of protein and large mounds of discarded shells and fish bones attest to the prehistoric human settlements that existed in Sarasota and were sustained by the bounty of its bay.

People living in the area of the present boundaries of Sarasota were part of the Manasota culture, an archaeological culture that existed in the area from Pasco County to Sarasota County from about 500 B.C. until about 900.[3] The Safety Harbor culture, which developed out of the Manasota culture around 900, covered much of the same area. Safety Harbor sites continued to be occupied after the Spanish reached Florida, as European artifacts have been found in the sites. Safety Harbor people built temple mounds in the primary towns of their chiefdoms. About twenty temple mound sites are known, including the Whitaker Mound that used to stand near Sarasota Bay in what is now downtown Sarasota,[4] "Mound Street" being named for it. The Whitaker Mound, and a number of other mounds in what is now Sarasota, were destroyed in the twentieth century to make room for development.[5] Others were convenient sources of shell used in road paving.

Early historical records[]

Spanish exploration[]

Europeans first explored the area in the early sixteenth century. The first recorded contact was in 1513, when a Spanish expedition landed at Charlotte Harbor, just to the south. Spanish was used by the natives during some of the initial encounters, however, providing evidence of earlier contacts.

In 1539, Spanish Conquistador Hernando de Soto sailed into South Tampa Bay and made landing at Little Manatee River. On early maps, the smaller bay along the coast to the south and the areas of contemporary Bradenton and Sarasota were identified as Zara Zota, Zara Sota, Sarazota, or Sarasota on maps.

Earliest settlement[]

The sheltered bay and its harbor attracted fish and marine traders. Soon there were fishing camps, called ranchos, along the bay that were established by both Americans and Cubans who traded fish and turtles with merchants in Havana. Florida changed hands between the Spanish, the English, and then the Spanish again. There were three claimants to Spanish land grants in and around Sarasota Bay, which were not confirmed by the United States.[6] With the Treaty of Moultrie Creek in 1823, all of the remaining Native Americans who had lived in the area were pushed to a reservation in the interior of Florida.

Fort Armistead[]

In May 1840, Brigadier Gen. Walker Keith Armistead established Fort Armistead in Sarasota along the bay. Fort Armistead was established because Armistead wanted to move against Native American settlements to the south of Fort Brooke. This was due to the fact that Native Americans were raiding because of the lack of resources in areas to which they were being restricted. It even became the southern headquarters for Fort Brooke. The fort is thought to have been located in the Indian Beach area. It was short-lived and only existed for seven months.[7] The army established the fort at a rancho operated by Louis Pacheco, an African slave working for his Cuban-American owner.[citation needed] Shortly before the fort was abandoned because of severe epidemics, the chiefs of the Seminole tribe gathered to discuss their impending removal to the Indian Territory. These were Native Americans who had moved into Florida during the Spanish occupation. They mostly had maintained permanent settlements that were used from late fall through spring, moving to settlements farther north during the summer. Most of the indigenous natives of Florida, such as the Tocobaga and the Caloosa, had perished from epidemics carried by the Spanish.

Soon the remaining Seminoles were forced south into the Big Cypress Swamp and, in 1842, the lands in Sarasota, which then were held by the federal government, were among those opened to private ownership by those of European descent via the Armed Occupation Act passed by the Congress of the United States. Even Louis Pacheco was deported with the Native Americans to Oklahoma.

Pioneer families[]

European settlers arrived in significant numbers in the late 1840s. The area already had a Spanish name, Zara Zote, on maps dating back to the early eighteenth century, and it was retained as Sara Sota. The initial settlers were attracted by the climate and the beauty and bounty of Sarasota Bay.

Sarasota has been governed by several different jurisdictions. Not becoming a state until 1845, Florida was acquired by the United States as a territory in 1819. Hillsborough County was created from Alachua and Monroe counties in 1834 and many early land titles cite it as the county governing Sarasota. Hillsborough was divided in 1855, placing Sarasota under the governance of Manatee County until 1921, when three new counties were carved out of portions of Manatee. One of those new counties was called Sarasota, and the city was made its seat. The boundary of the community once extended to Bowlees Creek, but that was redrawn to an arbitrary line in order to divide the airport so its oversight could include both counties. Property records and street addresses north of that new county line and south of the creek, however, remain as "Sarasota" due to established postal designations, although they remain governed by Manatee County.

Whitaker[]

William Whitaker was the first documented pioneer of European descent to settle permanently in what became the village of Sarasota.[8] After time spent along the Manatee River at the village of Manatee, Whitaker built upon , just north of present-day Eleventh Street. He sold dried fish and roe to Cuban traders working the coast and in 1847, he began a cattle business. In 1851, Whitaker married Mary Jane Wyatt, a member of a pioneer family who had settled the village of Manatee, that was about 13 mi (21 km) to the northeast along the river of the same name.

Their homestead site was not preserved, being razed in the 1990s, however, their family cemetery remains. In the 1930s, the Whitaker family gave the cemetery to the Daughters of the American Revolution on the understanding that any lineal descendants of William and Mary Whitaker and their spouses could be buried there as long as space remained.

Edwards[]

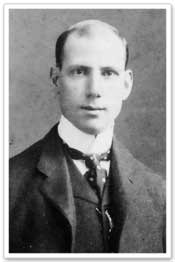

In 1874, Arthur Britton Edwards, better known as A. B. Edwards, was born in what now is The Uplands neighborhood on bayfront land homesteaded earlier by his parents through the federal armed occupation act. His parents died when he was fourteen and he became the sole support of his siblings. Eventually, he would become a major contributor to the attraction of migrants to and developers of Sarasota and, when the community changed its form of government to that of a "city", he was elected its first mayor and began to serve on January 1, 1914.[9][10]

Webb[]

In 1867, John G. Webb and his family moved from Utica, New York to Florida, looking for a place to settle. After arriving in Key West, the pioneer family met a Spanish trader. He told them about a high bluff of land on Sarasota Bay that would make a good location for a homestead.[11] When the Webbs arrived in Sarasota looking for the bluff, they described it to Bill Whitaker. He led them right to it because of the description. The site was several miles south of the settlement of the Whitakers. According to the nonprofit organization bearing its name and maintaining the property today, after settling, the Webbs named their homestead Spanish Point, in honor of the trader.

The Webb family planted citrus, sugar cane, and many vegetables. They also built a packing house to prepare produce for market. To transport the produce, John’s sons Jack and Will, along with son-in-law, Frank Guptill, built a ten-ton schooner called Vision. To encourage winter boarders to come stay at the property, the family established what is likely the first tourist resort in the area by building a dormitory for guests. The building, built in 1885 by son Jack Webb, is now known as White Cottage.[12]

In 1884, John Webb petitioned for a separate postal address for Spanish Point. They chose Osprey as their postal address, since federal regulations required the use of only one word for the new address. A separate town eventually grew around that postal address. Although there is no similar documentation regarding the name of Sarasota, that federal one-word rule for postal designations may be the reason that Zara Zota or Sara Sota became Sarasota.[improper synthesis?]

Lewis Colson[]

Born in 1844, Lewis Colson came to Sarasota as a surveyor with the Florida Mortgage and Investment Company in 1894. Colson was a former slave, a fisherman, landowner and Reverend in early Sarasota. He and his wife Irene, a midwife, settled in the neighborhood then known as Black Bottom (later known as Overtown). During his early years, Colson worked for engineer Richard E. Paulson. He later donated property to build the city's first African American Church, Bethlehem Baptist Church. Colson was its reverend from 1899 to 1915.[13] Historian Annie M. McElroy describes Colson as " one of the most respected black men in Sarasota during his lifetime".[14] In the early years of Overtown, black residents developed a thriving community with businesses, shops, churches, and social centers. The Colson Hotel, constructed in 1926, was named in Lewis Colson's honor, and catered to African American tourists up until the 1950s when it was renamed the Palm Hotel. Colson Avenue is also named in his honor. A historical marker at Five Points Park in downtown Sarasota, credits Colson as the "former slave [and] respected community leader... who drove the stake that marked the center of Five Points."[15] Colson, who died in 1922, and his wife Irene, are the only African Americans buried in Rosemary Cemetery.

Browning and Gillespie[]

In 1885 a Scots colony was established in Sarasota, which at the time was portrayed as a tropical paradise that had been built into a thriving town.[16] A town had been platted and surveyed before the parcels were sold by the Florida Mortgage and Investment Company. When the investors in the "Ormiston Colony" arrived by ship in December, they found that their primitive settlement lacked the homes, stores, and streets promised.

Only a few Scots, such as the Browning family, remained in Sarasota along with a determined member of the developer's family, John Hamilton Gillespie. He was a manager for Florida Mortgage & Investment Company and began to develop Sarasota following the plan for the failed colony. In 1887, he built the De Sota Hotel which opened on February 25 hosting a large social event and celebration. Eventually, tourists arrived at a dock built on the bay. In May 1886 he completed a two-hole golf course. By 1905, he had completed a 110-acre (45 ha) nine-hole course.

Owen Burns[]

Owen Burns had come to Sarasota for its famed fishing and remained for the rest of his life.[17][better source needed] He became the largest landowner in the city, founded a bank, promoted the development of other businesses, and built its bridges, landmark buildings, and mansions. He dredged the harbor and created new bayfront points with reclaimed soils. He created novel developments such as Burns Court (located in what now is referred to as Burns Square) to attract tourists and built commercial establishments to generate additional impetus to the growing community.

He also went into a business partnership with John Ringling to develop the barrier islands, a fateful decision that bankrupted him when his partner failed to live up to commitments on development agreements. In 1925 Burns built the El Vernona Hotel, naming it after his wife, Vernona Hill Freeman Burns. Shortly after the opening of the hotel, the land boom crash in Florida struck a fatal blow to his finances because of the unfulfilled partnership agreement. Ironically, it was the same former partner, John Ringling, who took advantage of the situation and purchased the hotel for a portion of its value, although several years later, with the crash of the stock market, Ringling would meet the same financial fate.

Beside the landmarks, bridges, and developments he built, Burns contributed to the attraction of many around the country to Sarasota. Among his five children, he also raised the most important historian for the community, his daughter, Lillian G. Burns.

Bertha Palmer[]

Bertha Palmer (Bertha Honoré Palmer) was the region's largest landholder, rancher, and developer around the start of the twentieth century, where she purchased more than 90,000 acres (360 km2) of property.[18] She was attracted to Sarasota by an advertisement placed in a Chicago newspaper by A. B. Edwards. They would maintain a business relationship for the rest of her life. The Palmer National Bank, established on Main Street at Five Points, remained a strong bank led by her sons through the depression and merged with Southeast Bank in 1976.[19]

Bertha Palmer also owned a large tract of land that now is Myakka State Park. During this period this land was operated as a ranch. She developed and promoted many innovative practices that enabled the raising of cattle to become a large-scale reality in Florida. At her "Meadowsweet Farms", Palmer also pioneered large-scale farming and dairy in the area and made significant contributions to practices that enabled the development of crops that could be shipped to markets in other parts of the country. Her experimentation was coordinated with the state department of agriculture.

As war in Europe threatened, Bertha Palmer touted the beauty of Sarasota and its advantages to replace the typical foreign destinations of her social peers. Palmer made her winter residence on the land which the Webb family had homesteaded. She built a resort that would appeal to these new visitors to the area. She quickly established Sarasota as a fashionable location for winter retreats of the wealthy and as a vacation destination for tourists, which endured beyond the war years and blossomed for the new wealth that developed more broadly in the United States during the 1920s and, after the Second World War as well.[20]

In her early publicity, Palmer compared the beauty of Sarasota Bay to the Bay of Naples, and also touted its sports fishing. As the century advanced, the bounty of the bay continued to attract visitors, until overfishing depleted its marine life.

Palmer retained most of the original Webb Family structures and greatly expanded the settlement. The pioneer site has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places as Historic Spanish Point and is open to the public for a fee. Her tourist accommodations at The Oaks have not been preserved, however.

Also arriving in 1910, Owen Burns closely followed Bertha Palmer to Sarasota and with two purchases, he quickly became the largest landholder within what now is the city, therefore many of the huge Sarasota properties she owned are in what now is Sarasota County (which did not exist during her lifetime). Many of its roads bear the names she put on the trails she established. She did participate, however, in speculation in the city along with others, purchasing undeveloped land in great quantities, and many parcels bear her name or that of her sons among those in abstracts.

Her sons continued her enterprises and remained as investors and donors in Sarasota after the death of Bertha Palmer in 1918. Aside from drawing worldwide attention to the city as a vacation destination and a chic location for winter residences, as well as being renowned for the ranching and agricultural reforms she introduced, two state parks are located on properties she held, portions of the Oscar Scherer State Park and the enormous Myakka River State Park, that may be counted as her greatest tangible legacy to Sarasotans.

20th & 21st century[]

1900s & 1910s[]

1900s[]

Sarasota was incorporated as a town on the night of October 14, 1902 having a population of 53 residents with John Hamilton Gillespie being sworn in as mayor and a city charter being created. It was later re-platted in 1912 and then incorporated as a city in 1913, with A. B. Edwards being its first mayor as a city.[21]

Other communities in the area were incorporated or began to grow into towns that were quite distinct from the bayfront community whose plat ended at what is now Tenth Street. They were later absorbed as Sarasota grew, but some have retained their names and are recognized today as neighborhoods. Some communities, such as Overtown, Bay Haven, Indian Beach, Shell Beach, Bee Ridge, and Fruitville have all but faded from the memory of most living there now. Overtown expanded to include what now is designated as the historic Rosemary District and the boundaries of Newtown now merge with that. The Ringling College of Art and Design includes for its administration building, a hotel developed for the community of Bay Haven when Old Bradenton Road was the main thoroughfare north to the Manatee River. Tamiami Trail was developed in the mid-1920s and a bridge across the creek eliminated it as a natural barrier limiting development. Shell Beach became the location where the grand estates would be built on the highest land along the bay as well as where the Sapphire Shores and The Uplands developments are today.

Another major factor that helped this area grow was the railroad. In 1902, a railroad bridge was built across the Manatee River about 11 miles north. The bridge was built by the . Ten years after this in 1912, the first leading to Bradenton was built.[22]

1910s[]

Introduction of the Ringling family[]

Mary Louise and Charles N. Thompson platted Shell Beach in 1895. The Thompson home was the first residence on the property. It extended from what is now Sun Circle almost to Bowlees Creek. From 1911 onwards, Mable and John Ringling spent their winter stays in that house and eventually, they would purchase a large parcel of Thompson property for their permanent winter quarters in Sarasota. Along with being a land developer, Thompson was a manager with another circus. He attracted several members of the Ringling family to Sarasota as a winter retreat as well as for investments in land. The Ringling brothers did not yet have their immense circus wealth yet as the Ringling Brothers Circus had not yet consolidated as a single entity.

First, the Alf T. Ringling family settled in the Whitfield Estates area with extensive land holdings. The families of Charles and John Ringling followed, living farther to the south. Soon, children and members of the extended family increased the presence of the Ringling family in Sarasota. Following the death of Alf T. in 1919, Charles Ringling assumed many of his duties.

Charles Ringling would invest in land, develop property, and found a bank. He participated in Sarasota's civic life and gave advice to other entrepreneurs starting new businesses in Sarasota. From his bank, he loaned money to fledgling businesses. Encouraging its creation, he donated land to the newly formed county—upon which he also built its government offices and courthouse as a gift to the community.

Ringling Boulevard would be named for Charles Ringling. Ringling Boulevard is a winding road leading east from the bayfront at what now is Tamiami Trail toward the winter circus headquarters. It crosses Washington Boulevard where Charles Ringling built the Sarasota Terrace Hotel, a high-rise in the Chicago style of architecture, opposite the site which Ringling would donate for the county seat. It was readily accessible by train at the time.

Charles Ringling and his wife, Edith, began building their bayfront winter retreat in the early 1920s. Charles Ringling died in 1926, just after it was completed. For decades Edith Ringling remained there and continued her role in the administration of the circus, assuming many duties of her husband, and her cultural activities in the community. Her daughter, Hester, and her sons were active in Sarasota's theatrical and musical venues. What came to be known internationally as the Edith Ringling Estate is now the center of the campus of New College of Florida.[23][24]

New Developments[]

During the 1910s, many modern improvements such as: the city's sewage & water system would become able to cover the entire city by the early 1910s[25] and the first paved road leading to Venice would be built.[26]

In 1913, two sisters Katherine McClellan and Daisietta McClellan became real estate developers creating the McClellan Park subdivision In their plat filed from that year, it was unique in the way that it deviated from the typical grid system used for large developments. It provided a yacht basin, tennis courts, and other recreational sport facilities.

is an artificial island that was created during this period. Starting in 1914, an 8 foot (2.4 m) deep channel was dredged with the intent of creating a port at Payne Terminal, located at Centennial Park, and with warehouses on the island. The port venture was not successful, used by only a few ships. Most of the docks later burned.[27]

Post World War I expansion wave[]

Following the end of World War I, an economic boom began in Sarasota. The city would be flooded with new people seeking jobs, investment, and the chic social milieu that had been created by earlier developers.

During the 1920s, Sarasota would build upon its progress made in the last decade. Electricity would become reliable with the building of an FPL power station in June 1920. During the early 1920s a bond issue would be approved to pay for improving the existing plant, extending power lines and constructing two new power stations. However only one new power station would be built.[28]

On adjacent parcels of Thompson's Shell Beach where Ellen and Ralph Caples built their winter retreat, Mable and John Ringling would build their compound and it soon would include the museum. Edith and Charles Ringling built a compound that included a home for their daughter, Hester Ringling Lancaster Sanford.

The next large Shell Beach parcel, immediately to the north, passed between Ellen Caples, Mable and John Ringling, and a few others several times without development until 1947. It was then developed as The Uplands. Some other historic names associated with that parcel are Bertha Palmer, her son Honoré, whose names are featured as familiar street names in Sarasota, and A.B. Edwards.

The tract abutting that parcel was re-platted in 1925 as Seagate with the intention of creating an entire subdivision. This is where Gwendolyn and Powel Crosley built their winter retreat in 1929.[29] All of these historic homes and the museum have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

John Ringling would invest heavily in the development of the barrier islands, known as keys, which separate the shallow bay from the Gulf of Mexico. Although he had several corporations and development projects in Sarasota, he did work in partnership with Owen Burns to develop the keys through a corporation named Ringling Isles Estates. Burns would own all of Lido Key. To facilitate the development of these holdings a bridge was built to the islands by his partner, Owen Burns. Eventually, Ringling donated the bridge to the city for the government to maintain. They named that route, John Ringling Boulevard. The center of Saint Armand key contains Harding Circle and the streets surrounding it are named for other U.S. presidents. Dredge and fill by Owen Burns created even more dry land to develop, including Golden Gate Point. Winter residents, called snowbirds, flocked to purchase these seasonal homes marketed to the well-to-do.

The now-historic neighborhood of Indian Beach Sapphire Shores grew immediately to the south of the area where these grand homes were built on the bay. Sapphire Shores provided homes to the professionals and retirees who wished to be, or were, closely associated with these wealthiest residents of the community. Indian Beach, which had been a separate community at one time, contained pioneer homes that survived among the fashionable new homes built during the boom era of the 1920s.

New city plan[]

In 1925 John Nolen, a professional planner, was hired to develop a plan for the downtown of the city. He laid out the streets to follow the arch of the bayfront with a grid beyond, that extended north to what is now Tenth Street and south to Mound. This followed more closely the way the city was developing at the time.

The new plan accentuated that city hall on the bayfront, was the nexus of the city. Broadway, the road that connected the downtown bayfront with the northern parts of the city along the bay had become part of the new Tamiami Trail that was being created. The trail was a portion of U.S. 41 that connected Tampa to Miami (hence the contracted name) in 1928. United with U.S. 301 in northern Manatee County, the trail made a "dog's leg" turn toward the west at Cortez Road. In Sarasota it turned back toward the east to follow Main Street through downtown before rejoining U.S. 301 at Washington Boulevard. Sarasota City Hall, situated in the Hover Arcade at the foot of Main Street, was on the waterfront and the city dock extended from it. It was the hub of the city. Vehicles and materials could pass through the arcade and railroad tracks led directly to the terminus.

Florida land boom crash, Great Depression and World War II[]

The Roaring Twenties ended early for Sarasota. Florida was the first area in the United States to be affected by the financial problems that led to the Great Depression. In 1926 development speculation began to collapse with bank failures on the eastern coast of Florida, much earlier than most parts of the country. The financial difficulties spread throughout Florida. John Ringling initially profited from the economic crash. Ringling had put his partner, Owen Burns, into bankruptcy by using money from the treasury of their corporation for use on another Ringling project that was failing. He later purchased the landmark El Vernona Hotel from Burns at a fraction of its worth. John Ringling, too, however, lost most of his fortune. Shortly after the June 1929 death of his wife, Mable, his reversal began because his stock investments were affected.

Just before the market crashed, Ringling had purchased several other circuses with hopes of combining them with the existing circus and selling shares on the stock exchange. The crash ended that plan. While Ringling continued to invest in expensive artwork, he left grand projects unfinished, such as a Ritz hotel on one of the barrier islands. He abandoned plans for an art school as an adjunct to the museum. Ringling did lend his name to an art school established by others in Sarasota, however reluctantly.

The board of the circus, which included Edith Ringling and other members of the family, removed John Ringling and placed another director in charge of the corporation. By the time of his death in 1936, John Ringling was close to bankruptcy. His estate was saved only because he had willed it, together with his art collection, to the state and he died just before he would have become bankrupt.

Despite the Great Depression, several projects were completed in the city with WPA and CCC funding notably: the Municipal Auditorium, Bayfront Park, Sarasota-Bradenton Airport, and Lido Casino.[30]

1950s - 1990s[]

In the 1950s, the names and numbers of the downtown streets were changed to their present ones. Originally, numbered streets would began at Burns Square and Burns' triangular building, separating the intersection of Orange and Pineapple Avenues, was on First Street. The existing numbered streets were shifted six blocks north, beginning above what is now Main Street.[citation needed]

Nolan's original plan would be abandoned in the 1960s when pressure to increase speeds on Tamiami Trail drove the demolition of the city hall and the redirection of the route past the bayfront, severing the community from the waterfront. By the last decade of the century, automobile traffic had become so dominant that intersections beyond human-scale barred all but the most adventurous from attempting crossings on foot. At community planning charrettes, designs began to circulate that called for the reunification of the downtown to the bayfront and removal of the designation of the bayfront road as a highway. New Urbanism concepts focused upon restoring Sarasota to being a walkable community and taking the greatest advantage of its most beautiful asset, Sarasota Bay. Roundabouts were discussed as traffic calming devices that could be integrated into gracious designs for safe and efficient movement of automobiles among increased use by bicyclists and pedestrians, along with a reduction of pollution.[citation needed]

Civil Rights movement[]

Like many other cities in the United States, it would see action occurring in it during the Civil Rights Movement. Sarasota was similar to many other places in the United States having racial segregation in it. Any African-American resident going outside of Overtown and/or Newtown had to receive a work permit or permission from there employer. The Sarasota NAACP chapter would organize a wade-in protest on October 2, 1955 after residents in the area had asked for a beach for them to use for several years.[31] After the protest occurred, a majority of local residents overall along with the city and county commissions would be in favor of creating a beach for African Americans. However both the city and county commissions could not find a spot. somewhere on Longboat Key, Siesta Key along Big Pass, Siesta Key's side of Midnight Pass along with an artificial beach. Both Siesta Key locations were determined to not be suitable as a beach site because of either the fast currents or a need for dredging. At the Longboat Key and Siesta Key their would be significant opposition from local residents in the area. Longboat Key residents would hold meetings as a way to protest the beach being located there and decided to incorporate themselves as a way of avoiding the placement of the beach there.[32] Protests would occur in Sarasota on a weekly basis until the beaches would be desegregated.[31]

However though, the city government was strongly against doing integration of the beaches. A city ordinance would be passed on September 4, 1956 that would allow the Sarasota Police Department to remove all people at a public beach in city limits if there were two racial groups present at once. After not being successful with getting a beach, the city commission would propose creating a pool in Newtown instead; with the pool opening in November 1957. During the pool's construction the protests would pause but they would resume once again after the pool itself reopened as African Americans still wanted to have their own beach.[31] Also during 1957, the NAACP would request the Sarasota County School Board to desegregate there public schools but did not do so. In 1961, the NAACP filed a lawsuit against the school board for not desegregating its schools[33] and the federal government that year would also threaten Sarasota's municipal government with taking away its anti-beach erosion funding if it continued to segregate its beaches.[31]

During 1962 the county school board would integrate its first school, Bay Haven Elementary located in Sarasota city proper allowing Black students to enroll. It is unclear exactly when beaches in the city would be desegregated as it was never formally done but it is assumed to have happened when the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed.[31] With the passing of the Civil Rights Act, it would order that all schools integrate by 1967. To accommodate for this, the Sarasota County School Board would close the African American schools Booker Junior High School in 1967 and Booker High School the following year. It would bus students to existing all-white schools.[33] In 1967, the city would end up passing an ordinance against interracial beaches. Protests would occur against it until the ordinance was ended at an unknown point.[34]

Booker Elementary and Amaryllis Park Primary School would close in 1969. The local NAACP would send a resolution to the county school board asking if they could bus white students to the Booker schools but the board ended up rejecting the plan. Many local African American residents supported integration but felt a sense of pride in their own local schools. African American students going to predominantly white schools led to much tension occurring at those schools. A local meeting would be held at the Newtown Community Center on May 3, 1969 to take action against the school district's integration plan. By the end of the meeting attendees agreed that attending local "Freedom Schools" established outside of the school district to protest. It would begin the next day and last for another five days. During its final day on May 9 the school district made a decision to keep both Booker Elementary and Amaryllis Park Primary School open and take action against the students and their parents who missed class. Booker Elementary became a magnet school as a way to encourage white students to voluntarily join. Booker High School and Booker Junior High School would follow suit doing the same thing in 1970.[33]

21st century[]

On September 11, 2001, President George W. Bush was reading The Pet Goat in Emma E. Booker Elementary School when he was informed of the attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City. Mohamed Atta and co-conspirator Marwan al-Shehhi, who piloted the hijacked jets, undertook part of their pilot training at Jones Aviation in Sarasota County during 2000.[35]

Sarasota became identified as an epicenter of the 2008 real estate crash.[36][37] It followed financial credit problems that began with poorly financed mortgages failing because of massive real estate speculation that began in the late 1990s and escalated dramatically during the early 2000s.[38] Once the values of the properties began to fall the mortgages purchased with consideration of "equity value" derived from the rapid increases in property values due to speculation became problematic. The properties were no longer worth the value of the mortgages, some by great differences. This became almost a nationwide problem and occurred in other countries as well.

2010s[]

In 2010, an island in Sarasota was temporarily renamed "Google Island" in an attempt to get Google Fiber for the city.[39]

In January 2017, an estimated 10,000 protesters marched across the John Ringling Causeway in solidarity with woman's organizations around the world. The protest would one of the largest in Sarasota's history.[40]

References[]

- ^ "The Origin of the Name, Sarasota". www.sarasotahistoryalive.com. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ "Sarasota History". History & Preservation Coalition of Sarasota County. 21 October 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ Luer, George M.; Marion M. Almy (March 1982). "A Definition of the Manasota Culture". The Florida Anthropologist. 35 (1): 34–36. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ^ Luer, George M.; Marion M. Almy (September 1981). "Temple Mounds of the Tampa Bay Area". The Florida Anthropologist. 34 (3): 127–155. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ^ Luer, George M. (March 2011). "The Yellow Bluffs Mound Revisited: a Manasota Period Burial Mound in Sarasota". The Florida Anthropologist. 64 (1): 5–32 – via University of Florida Digital Collections.

- ^ * Florida, State Library and Archives of. "Godoya, Jose M." Florida Memory. Retrieved 2018-11-22.

- Florida, State Library and Archives of. "Gomez, Antonio". Florida Memory. Retrieved 2018-11-22.

- Florida, State Library and Archives of. "Gonzales, Andrew". Florida Memory. Retrieved 2018-11-22.

- Congress, United States (1860). "Land Claims in East Florida". American State Papers: Documents, Legislative and Executive, of the Congress of the United States ... Gales and Seaton. pp. 107–09.

- ^ "A Military Post on Sarasota Bay | Sarasota History Alive!". www.sarasotahistoryalive.com. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- ^ Burnett Gene M. (1986) Florida's Past: People and Events that Shaped the State. Pineapple Press Inc., Sarasota, FL

- ^ Sarasota History Alive!, From Mayor to Myakka - A. B. Edwards, People: Sarasota History

- ^ LaHurd, Jeff, A. B. Edwards was always in the thick of growing Sarasota, Sarasota Herald Tribune, July 20, 2014

- ^ https://www.venicemagazineonline.com/eat-and-drink/2017/10/webb-family-venice

- ^ https://www.historicspanishpoint.org/about-us/history/pioneers/

- ^ Lahurd, Jeff; Herald-Tribune. "Lewis Colson". Newtown 100. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- ^ But Your World and My World: The Struggle for Survival : a Partial History of Blacks in Sarasota County, 1884–1986. Black South Press. 1986-01-01.

- ^ "City of Sarasota – Florida Historical Markers on Waymarking.com". www.waymarking.com. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- ^ "Preserve America Community: Sarasota, Florida". Preserve America. March 4, 2009. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "Owen Burns". www.owenburns.com.

- ^ "Mrs. Bertha Palmer's Vision". Sarasota History. Archived from the original on 3 October 2010. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "Bertha Palmer's Vision: Her Impact on Sarasota". Sarasota History Alive. Archived from the original on 2010-10-03.

- ^ "?". Sarasota County Government.

- ^ "The City of Sarasota Should Ditch the David and Embrace its Fishy Heritage". Sarasota Magazine. Retrieved 2019-04-13.

- ^ "Ashton Home | Sarasota History Alive!". www.sarasotahistoryalive.com. Retrieved 2016-01-18.

- ^ Benz, Kafi, Residence of Hester Ringling Lancaster Sanford Archived 2011-10-03 at the Wayback Machine, Sarasota History Alive!, Journals of Yesteryear, April 29, 2009

- ^ Benz, Kafi, Residence of Edith Ringling Archived 2011-10-03 at the Wayback Machine, Sarasota History Alive!, Journals of Yesteryear, December 8, 2010

- ^ Smith, Mark D. "Sewage a Pesky Problem for Years in Sarasota". Sarasota History Alive!. Retrieved 2020-12-28.

- ^ Shank, Ann A. "The 'Velvet Highway'". Sarasota History Alive!. Retrieved 2020-12-28.

- ^ Smith, Mark. "A Variety of Ventures for City Island | Sarasota History Alive!". Sarasota History Alive!. Retrieved 2019-03-31.

- ^ Shank, Ann A. "Early Power for Sarasota Unreliable & Inconsistent". Sarasota History Alive!. Retrieved 2020-12-27.

- ^ LaHurd, Jeff, Powel Crosley, Jr. remembered as a visionary, Sarasota Herald Tribune, Sunday, November 15, 2015, page B-1

- ^ "The Living New Deal | New Deal Sites, Map". The Living New Deal. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "A Brief History of the Struggle for Beach Integration in Sarasota" (PDF).

- ^ Westcott, Adam. "The Integration of Sarasota Beaches". Sarasota History Alive!. Retrieved 2021-05-27.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Janko, Erica (March 29, 2015). "Sarasotan Students' school boycott stops neighborhood schools from closing, Florida, United States, 1969". Global Nonviolent Action Database. Retrieved 2021-05-27.

- ^ "Visit the Newtown Historic Timeline - Newtown Alive". Newtown Alive. Retrieved 2021-05-27.

- ^ The 9/11 Commission report: Final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (2004). New York: Norton. p224

- ^ Callan, Eoin (2007-08-09). "Florida at centre of US housing bust". FT.com. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ^ Braga, Michael (2007-08-11). "In globe's financial crunch, ground zero is ... Sarasota?". HeraldTribune.com. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ^ [1] Archived March 14, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Van, Eliot. (2013-03-28) Al Franken Jokes, But Google Fiber Is No Laughing Matter | Wired Business. Wired.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-17.

- ^ Djinis, Elizabeth. "Thousands turn out for Sarasota Women's Solidarity March".

- Sarasota, Florida

- Histories of cities in Florida