History of United States drug prohibition

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2013) |

This is a history of drug prohibition in the United States.

Efforts to regulate the sale of pharmaceuticals began around 1860, and laws were introduced on a state-to-state basis that created penalties for mislabeling drugs, adulterating them with undisclosed narcotics, and improper sale of those considered "poisons". Poison laws generally either required labels on the packaging indicating the harmful effects of the drugs or prohibited sale outside of licensed pharmacies and without a doctor's prescription. Prominent pharmaceutical societies at the time supported the listing of cannabis as a poison.[1]

In 1880, the U.S. and Qing Dynasty China completed an agreement prohibiting the shipment of opium between the two countries; Qing China itself was still reeling from the effects of fighting the Opium War after a failed attempt to stem the British importing of opium into China proper (see Lin Zexu).

The rate of opiate addiction increased from about .72 addicts per 1,000 people to a high of 4.59 per 1,000 in the 1890s.[2]

In 1906 the Pure Food and Drug Act requires that certain specified drugs, including alcohol, cocaine, heroin, morphine, and cannabis, be accurately labeled with contents and dosage. Previously many drugs had been sold as patent medicines with secret ingredients or misleading labels. Cocaine, heroin, cannabis, and other such drugs continued to be legally available without prescription as long as they were labeled. It is estimated that sale of patent medicines containing opiates decreased by 33% after labeling was mandated.[3]

1911: United States first Opium Commissioner, Hamilton Wright argues that of all the nations of the world, the United States consumes most habit-forming drugs per capita.[4]

1913: The American Medical Association created a propaganda department to outlaw health fraud and quackery.[5] In the same year, California outlawed cannabis.

1914: The first recorded instance of the United States enacting a ban on the domestic distribution of drugs is the Harrison Narcotic Act[6] of 1914. This act was presented and passed as a method of regulating the production and distribution of opiate-containing substances under the commerce clause of the U.S. Constitution, but a [1] section of the act was later interpreted by law enforcement officials for the purpose of prosecuting doctors who prescribe opiates to addicts.

1919: Alcohol prohibition in the U.S. first appeared under numerous provincial bans and was eventually codified under a federal constitutional amendment in 1919, having been approved by 36 of the 48 U.S. states.

1925: United States supported regulation of cannabis as a drug in the International Opium Convention.[7] and by the mid-1930s all member states had some regulation of cannabis.

1930: The Federal Bureau of Narcotics was created. For the next 32 years it was headed by Harry J. Anslinger who came from the Bureau of Prohibition as did many of its initial members.

1932: Democrat Franklin Roosevelt ran for President of the United States promising repeal of federal laws of Prohibition of alcohol.

1933: Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution is repealed. The amendment remains the only major act of prohibition to be repealed, having been repealed by the Twenty-first Amendment to the United States Constitution.

1935: President Roosevelt hails the International Opium Convention and application of it in US. law and other anti-drug laws in a radio message to the nation.[8]

1937: Congress passed the Marijuana Tax Act. Presented as a $1 nuisance tax on the distribution of marijuana, this act required anyone distributing the drug to maintain and submit a detailed account of his or her transactions, including inspections, affidavits, and private information regarding the parties involved. This law, however, was something of a "Catch-22", as obtaining a tax stamp required individuals to first present their goods, which was an action tantamount to confession. This act was passed by Congress on the basis of testimony and public perception that marijuana caused insanity, criminality, and death.

1951: The 1951 Boggs Act increased penalties fourfold, including mandatory penalties.[9]

1956: The Daniel Act increased penalties by a factor of eight over those specified in the Boggs Act. Although by this time there was adequate testimony to refute the claim that marijuana caused insanity, criminality, or death, the rationalizations for these laws shifted in focus to the proposition that marijuana use led to the use of heroin, creating the gateway drug theory.[citation needed]

1965, in Laos, the CIA's airline, Air America, is suspected of flying Hmong (Meo) opium out of the hills to Long Tieng and Vientiane to obtain hard currency for their otherwise unfunded Hmong war against the Viet Cong in 1971.[10] During the Laotian Civil War, Long Tieng served as a town and airbase operated by the Central Intelligence Agency of the United States.[11]

The Golden Triangle (Southeast Asia) became a mass producer of high-grade no. 4 heroin for the American market.[12]

The first ever head shop, Ron and Jay Thelin's Psychedelic Shop, opened on Haight Street on January 3, 1966, offering hippies a spot to purchase marijuana and LSD, which was essential to hippie life in Haight-Ashbury.[13]

In 1969, psychiatrist Dr. Robert DuPont conducted a urinalysis of everyone entering the D.C. jail system in August 1969. He found 44% test positive for heroin and starts the first methadone treatment program in the Department of Corrections in September 1969 for heroin addicts.[14][15]

In 1970, the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) was enacted into law by Congress. The CSA is the federal U.S. drug policy under which the manufacture, importation, possession, use and distribution of certain substances is regulated. This legislation is the foundation on which the modern drug war exists. Responsibility for enforcement of this new law was given to the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs and then, in 1973, to the newly formed Drug Enforcement Administration. During the Nixon era, for the only time in the history of the war on drugs, the majority of funding goes towards treatment, rather than law enforcement.[14]

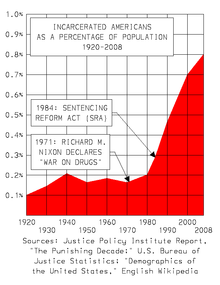

In June 1971, the Vietnam War was linked with concerns over drugs. The Nixon administration coined the term War on Drugs.[14][16][17] He characterized the abuse of illicit substances as "public enemy number one in the United States".

In May, 1971 Congressmen Robert Steele (R-CT) and Morgan Murphy (D-IL) released a report on the growing heroin epidemic among U.S. servicemen in Vietnam.[14]

Later in May 1971, the U.S. military announced they will begin urinalysis of all returning servicemen. The program goes into effect in September. 4.5% of the soldiers test positive for heroin.[14]

1972, March 22: The National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Abuse recommended legalizing possession and sales of small amounts of marijuana. This recommendation is ignored.[20]

1974: A Senate Internal Security Subcommittee on The Marihuana-hashish epidemic and its impact on United States security invited 21 scientists from seven different countries, including Gabriel G. Nahas and Nils Bejerot, to testify about the dangers of the drug.[21][22]

1979: Illegal drug use in the U.S. peaked when 25 million of Americans used an illegal drug within the 30 days prior to the annual survey.[23]

1986: The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 was enacted into law by Congress. It changed the system of federal supervised release from a rehabilitative system into a punitive system. The bill enacted new mandatory minimum sentences for drugs, including marijuana.

1988: Near the end of the Reagan administration, the Office of National Drug Control Policy was created for central coordination of drug-related legislative, security, diplomatic, research and health policy throughout the government. In recognition of his central role, the director of ONDCP is commonly known as the Drug Czar. The position was raised to cabinet-level status by Bill Clinton in 1993.

1990: The Solomon–Lautenberg amendment is enacted.[24] As a result, many states pass "Smoke a joint, lose your license" laws to punish any drug offense with a mandatory six month driver's license suspension.[25][26]

1992: Illegal drug use in the U.S. fell to 12 million people.[23]

1993: Joycelyn Elders, the Surgeon General, said that the legalization of drugs "should be studied", causing a stir among opponents.[27]

1998: The government commissioned the first-ever full study of drug policy, to be carried out by the National Research Council (NRC); the Committee on Data and Research for Policy on Illegal Drugs is headed by Econometrician Charles Manski.

2001: The National Research Council Committee on Data and Research for Policy on Illegal Drugs was published. The study revealed that the government had not sufficiently studied its own drug policy, which it called "unconscionable". (see more under Efficacy of the War on Drugs)

2001: 16 million in the U.S. were drug users.[23]

2008: Several reports stated the benefits of drug courts compared with traditional courts. Using retrospective data, researchers in several studies found that drug courts reduced recidivism among program participants in contrast to comparable probationers between 12% to 40%. Re-arrests were lower five years or more later. The total cost per participant was also much lower.[28] Office of National Drug Control Policy reports that the Actual youth drug use, as measured as the percent reporting past month use has declined from 19,4% to 14,8% among middle and high school students between 2001 and 2007.[29]

2009: Gil Kerlikowske, the current Director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, signaled that the Obama Administration would not use the term "War on Drugs," as he claims it is counter-productive and is contrary to the policy favoring treatment over incarceration in trying to reduce drug use. "Being smart about drugs means working to treat people who go to jail with a drug problem so when they get out and return to the communities you protect, you will be less likely to re-arrest them".[30]

2010: California Proposition 19 (also known as the Regulate, Control and Tax Cannabis Act) was defeated, with 53.5% of California voters voting "No" and 46.5% voting "Yes."[31]

2010: The Fiscal Year 2011 National Drug Control Budget proposed by the Obama Administration devoted significant new resources, $340 million, to the prevention and treatment of drug abuse.[32]

2012: Colorado and Washington (state) passed laws to legalize the consumption, possession, and sale of marijuana.

2014: Alaska, Minnesota and Oregon passed laws to legalize the consumption, possession, and sale of marijuana.

2016: recreational marijuana use was legalized in California, Massachusetts, Nevada and Maine.

2018: Michigan passed laws legalizing the consumption, possession, and sale of marijuana

2020: Oregon became the first state to decriminalize the consumption and possession of all drugs.[33]

See also[]

- Drugs in the United States

- Foreign policy of the United States

- Drug prohibition

- Timeline of cannabis legalization in the United States

References[]

- ^ "Chemist & druggist". Chemist & Druggist. 28: 68, 330. 1886.

- ^ Crawford, Sarah (February 2, 2018). "History repeats itself with opioid epidemic". Florida Today. Melbourne, Florida. pp. 10A. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ Musto, David F. (1999). The American Disease: Origins of Narcotic Control (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512509-2.

- ^ "Uncle Sam is the Worst Drug Fiend in the World, NY Times, March 12, 1911". Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ "AMA History -- Key Historical Dates".

- ^ "Harrison Narcotics Tax Act, 1914 - Full Text". Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ "The Geneva Conferences: Indian Hemp". Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ "Roosevelt Asks Narcotic War Aid - New York Times March 22, 1935". Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ History of drug legislation, The National Alliance of Advocates for Buprenorphine Treatment

- ^ McCoy, Alfred (1972). The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia. Harper & Row. pp. 244, 247, 263–264. ISBN 978-0060129019.

When political infighting among the Lao elite and the escalating war forced the small Corsican charter airlines out of the opium business in 1965, the CIA's airline, Air America, began flying Meo opium out of the hills to Long Tieng and Vientiane.

- ^ "Laos: Deeper Into the Other War". TIME. 1970-03-09. Archived from the original on October 30, 2010. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- ^ McCoy, Alfred (1972). The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia. Harper & Row. pp. 244, 247, 263–264. ISBN 978-0060129019.

Without air transport for their opium, the Meo faced economic ruin. There was simply no form of air transport available in northern Laos except the CIA's charter airline, Air America And according to several sources, Air America began flying opium from mountain villages north and east of the Plain of Jars to Gen. Vang Pao's headquarters at Long Tieng. Air America was known to be flying Meo opium as late as 1971. Meo village leaders in the area west of the Plain of Jars, for example, claim that their 1970 and 1971 opium harvests were bought up by Vang Pao's officers and flown to Long Tieng on Air America UH-lH helicopters. This opium was probably destined for heroin laboratories in Long Tieng or Vientiane, and ultimately, for GI addicts in Vietnam.

- ^ Tamony, Peter. "Tripping out in San Francisco". American Speech. 2nd ed. Vol. 56. N.p.: Duke UP, n.d. 98-103. JSTOR. Web. 13 Mar. 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Thirty Years of America's Drug War, a Chronology. Frontline (U.S. TV series).

- ^ "Interviews - Dr. Robert Dupont - Drug Wars - FRONTLINE - PBS". Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ Timeline: America's War on Drugs. April 2, 2007. NPR.

- ^ Drug War Archived 2007-08-19 at the Wayback Machine. A chronology on the Justice Learning site. Click an item on the left for more info and sources. Or click "show all" at the top right.

- ^ "I Was Wrong About the War on Drugs – It's a Failure". By Bob Barr. June 11, 2008. AlterNet.

- ^ "The solution to the failed drug war". By Jack A. Cole. September 13, 2008. Boston Globe.

- ^ "NORML.org - Working to Reform Marijuana Laws - NORML.org - Working to Reform Marijuana Laws". Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ "AIM Report - January B, 1986". Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ Marihuana-hashish epidemic and its impact on United States security: hearings before the Subcommittee to Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and Other Internal Security Laws of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, Ninety-third Congress, second session [-Ninety-fourth Congress, first session] .. (1974)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Developing Tomorrow's Drug Policy". Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ "States Are Pressed to Suspend Driver Licenses of Drug Users". The New York Times. Associated Press. November 16, 1990. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- ^ "Possess a Joint, Lose Your License": July 1995 Status Report, Marijuana Policy Project, archived from the original on October 8, 2007

- ^ Aiken, Joshua (December 12, 2016), "Reinstating Common Sense: How driver's license suspensions for drug offenses unrelated to driving are falling out of favor", Prison Policy Initiative, retrieved September 26, 2020

- ^ https://www.nytimes.com/1993/12/08/us/surgeon-general-suggests-study-of-legalizing-drugs.html

- ^ "Do Drug Courts Work? Findings From Drug Court Research - National Institute of Justice". Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ "Office of National Drug Control Policy" (PDF). Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ "Office of National Drug Control Policy". Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ "Supplement to the Statement of Vote Statewide Summary by County for State Ballot Measures" (PDF). Secretary of State's office. January 6, 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 4, 2011. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- ^ "Office of National Drug Control Policy" (PDF). Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ https://www.cbsnews.com/news/oregon-first-state-decriminalize-cocaine-heroin-measure-109/

- Drug policy of the United States

- History of drug control