History of capitalism

hideThis article has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Capitalism |

|---|

|

The history of capitalism is diverse. The concept of capitalism has many debated roots, but fully[quantify] fledged capitalism is generally thought by scholars[specify][weasel words] to have emerged in Northwestern Europe, especially in Great Britain and the Netherlands, in the 16th to 17th centuries. Over the following centuries, capital accumulated by a variety of methods, at a variety of scales, and became associated[by whom?] with much variation in the concentration of wealth and economic power. Capitalism gradually became the dominant economic system throughout the world.[1][2][need quotation to verify][3][need quotation to verify] Much[quantify] of the history of the past 500 years is concerned with the development of capitalism in its various forms.

Varieties of capitalism[]

It is an ongoing debate within the fields of economics and sociology as to what the past, current and future stages of capitalism are. While ongoing disagreement about exact stages exists, many economists have posited the following general states.[weasel words] These states are not mutually exclusive and do not represent a fixed order of historical change, but do represent a broadly chronological trend.[citation needed]

- [4]

- ,[5] sometimes known as market feudalism. This was a transitional form between feudalism and capitalism, whereby market relations replaced some but not all feudal relations in a society.

- Anarcho-capitalism

- Authoritarian capitalism

- Common-good capitalism[6][7]

- Compassionate capitalism

- Conscious capitalism

- Crony capitalism

- Democratic capitalism

- Financial capitalism, where financial parts of the economy (like the finance, insurance, or real estate sectors) predominate in an economy. Profit becomes more derived from ownership of an asset, credit, rents and earning interest, rather than productive processes.[8][9]

- [10]

- Industrial capitalism, characterized by its use of heavy machinery and a much more pronounced division of labor.[specify]

- Laissez-faire capitalism

- Late capitalism

- Monopoly capitalism, marked by the rise of monopolies and trusts dominating industry and other aspects of society. Often used to describe the economy of the late 19th and early 20th century.[citation needed]

- Neoliberal capitalism

- Racial capitalism

- Social capitalism

- Stakeholder capitalism is a theoretical system in which corporations are oriented to serve the interests of all their stakeholders. Among the key stakeholders are shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers, environment, and local communities.[11][12][13]

- State capitalism, where the state intervened to prevent economic instability, including partially or fully nationalizing certain industries. Some economists[who?] also include the economies of the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc in this category.[14]

- Surveillance capitalism

- Totalitarian capitalism

- Welfare capitalism, the implementation of laws and government funded social programs, such as minimum wage and universal healthcare, with the aim of creating a social safety net. The heyday of welfare capitalism (in advanced economies) is widely seen[by whom?] to be from 1945 to 1973 as major social safety nets were put in place in most advanced[vague] capitalist economies.[15]

- Woke capitalism

- Colonialism, where governments sought to colonize other areas to improve access to markets and raw materials and assist state-owned capitalist firms.[citation needed]

- Corporatism, where government, business and labor collude to make major national decisions. Notable for being an economic model of fascism,[citation needed] it can overlap with, but is still significantly different from state capitalism.[specify]

- Mass production, post-World War II, saw the rising power of major corporations and a focus on mass production, mass consumption and (ideally) mass employment. This stage[vague] sees the rise of advertising as a way to promote mass consumption and often sees significant economic planning taking place within firms.[16]

- Mercantilism, usually in historic context, is the use of a variety of economic policies that aim to protect domestic trade from foreign competition, commonly by raising tariffs on imported goods and giving subsidies to domestic producers.[citation needed]

Historiography[]

The processes by which capitalism emerged, evolved, and spread are the subject of extensive research and debate among historians. Debates sometimes focus on how to bring substantive historical data to bear on key questions.[17] Key parameters of debate include: the extent to which capitalism is a natural human behavior, versus the extent to which it arises from specific historical circumstances; whether its origins lie in towns and trade or in rural property relations; the role of class conflict; the role of the state; the extent to which capitalism is a distinctively European innovation; its relationship with European imperialism; whether technological change is a driver or merely an epiphenomenon of capitalism; and whether or not it is the most beneficial way to organize human societies.[18]

The historiography of capitalism can be divided into two broad schools.[citation needed] One is associated with economic liberalism, with the 18th-century economist Adam Smith as a foundational figure. The other is associated with Marxism, drawing particular inspiration from the 19th-century economist Karl Marx.

Liberals view capitalism as an expression of natural human behaviors that have been in evidence for millennia and the most beneficial way of promoting human well being.[citation needed] They see capitalism as originating in trade and commerce, and freeing people to exercise their entrepreneurial natures.[citation needed]

Marxists view capitalism as a historically unusual system of relationships between classes, which could be replaced by other economic systems that would serve human well being better.[citation needed] They see capitalism as originating in more powerful people taking control of the means of production, and compelling others to sell their labour as a commodity.[18] For these reasons, much of the work on the history of capitalism has been broadly Marxist.[citation needed]

Origins[]

The origins of capitalism have been much debated (and depend partly on how capitalism is defined). The traditional account, originating in classical 18th-century liberal economic thought and still often articulated, is the 'commercialization model'. This sees capitalism originating in trade. Since evidence for trade is found even in paleolithic culture, it can be seen as natural to human societies. In this reading, capitalism emerged from earlier trade once merchants had acquired sufficient wealth (referred to as 'primitive capital') to begin investing in increasingly productive technology. This account tends to see capitalism as a continuation of trade, arising when people's natural entrepreneurialism was freed from the constraints of feudalism, partly by urbanization.[19] Thus it traces capitalism to early forms of merchant capitalism practiced in Western Europe during the Middle Ages.[20]

Dutch Republic[]

In 1602 shares in the Dutch Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC, better known as the Dutch East India Company) were issued, suddenly creating what is usually considered the world's first publicly traded company. (...) There are other claimants to the title of first public company, including a twelfth-century water mill in France and a thirteenth-century company intended to control the English wool trade, Staple of London. Its shares, however, and the manner in which those shares were traded, did not truly allow public ownership by anyone who happened to be able to afford a share. The arrival of VOC shares was therefore momentous, because as Fernand Braudel pointed out, it opened up the ownership of companies and the ideas they generated, beyond the ranks of the aristocracy and the very rich, so that everyone could finally participate in the speculative freedom of transactions. By expanding ownership of its company pie for a certain price and a tentative return, the Dutch had done something historic: they had created a capital market.

— Kevin Kaiser and David Young (INSEAD), in "The Blue Line Imperative: What Managing for Value Really Means" (2013)[41]

egg

Its [the Dutch East India Company's] fame as the first public company, which heralded the transition from feudalism to modern capitalism, and its remarkable financial success for nearly two centuries ensure its importance in the history of capitalism.

— Warwick Funnell and Jeffrey Robertson, in "Accounting by the First Public Company" (2014)[42]

A chartered company, the first with publicly traded stocks, and—within a few decades of its foundation—the richest company in the world, the VOC was not merely a business interest. It constituted a politogen, even a state in itself. (...) One of the VOC's most groundbreaking achievements was to organize, practically alone, an intercontinental cycle of accumulation that was vital to the emergence of global capitalism and the modern state.

— Peter Gelderloos, in Worshipping Power: An Anarchist View of Early State Formation (2016)[43]

(...) If one looks closely at the Dutch in the seventeenth century we can see virtually every major feature of large-scale industry credited to the English two centuries later. Production was increasingly mechanised, as in sawmilling; standardised parts were deployed in manufacturing, especially in shipbuilding; modern financial markets were developed, underscored by the formation of the Amsterdam Bourse in 1602. And it was all underwritten by an agricultural system that did what all capitalist agricultures must do: produce more and more food with less and less labour-time.

— Jason W. Moore, Political Economy Research Centre (Goldsmiths, University of London), December 2017[44]

The role of Dutch-speaking lands, especially present-day Flanders and the Netherlands (in particular modern-day North Holland and South Holland), in the history of capitalism has been a much discussed and researched subject.[45][34][35][46][47][48][49][50] Capitalism began to develop into its modern form during the Early Modern period in the Protestant countries of North-Western Europe, especially the Netherlands (Dutch Republic)[51][52][53][54][55][56] and England: traders in Amsterdam and London created the first chartered joint-stock companies driving up commerce and trade, and the first stock exchanges and banking and insurance institutions were established.[57][58][59][60] The world's earliest recorded speculative bubbles and stock market crashes occurred in 17th-century Holland. Seventeenth-century Dutch mechanical innovations such as wind-powered sawmills and Hollander beaters helped revolutionize shipbuilding[61][62] and paper industries. The Dutch also played a pioneering role in the rise of the capitalist world-system.[63] World-systems theorists (including Immanuel Wallerstein and Giovanni Arrighi) often consider the economic and financial supremacy of the 17th-century Dutch Republic[64] to be the first historical model of capitalist hegemony.[52][53][65][66][56][67][68]

As Thomas Hall (2000) notes, "The Sung Empire in particular nearly underwent a transformation to capitalism in the tenth century C.E. But the only states to be controlled by capitalists before the European transformation in the 17th century were semiperipheral capitalist city-states such as the Phoenician cities, Venice, Genoa, and Malacca. These operated in the interstices between the tributary states and empires, and though they were agents of commodification, they existed within larger systems in which the logic of state-based coercion remained dominant. This coming to state power by capitalists in an emerging core region signaled the triumph of regional capitalism in the European subsystem."[69] In Werner Sombart's words, "In all probability the United Provinces were the land in which the capitalist spirit for the first time attained its fullest maturity; where this maturity related to all its aspects, which were equally developed; and where this development had never been done comprehensive before. Moreover, in the Netherlands an entire people became imbued with the capitalist spirit; so much so, that in the 17th century Holland was universally regarded as the land of capitalism par excellence; it was envied by all other nations, who put forth their keenest endeavours in their desire to emulate it; it was the high school of every art of the tradesman, and the well-watered garden wherein the middle-class virtues throve."[70] Foundational thinkers in this approach include Adam Smith, Max Weber, Fernand Braudel, Henri Pirenne, and Paul Sweezy.

Business ventures with multiple shareholders became popular with commenda contracts in medieval Italy (Greif 2006, 286), and Malmendier (2009) provides evidence that shareholder companies date back to ancient Rome. Yet the title of the world's first stock market deservedly goes to that of seventeenth-century Amsterdam, where an active secondary market in company shares emerged. The two major companies were the Dutch East India Company and the Dutch West India Company, founded in 1602 and 1621. Other companies existed, but they were not as large and constituted a small portion of the stock market.

— Edward P. Stringham and Nicholas A. Curott, in "The Oxford Handbook of Austrian Economics" [On the Origins of Stock Markets] (2015)[71]

The stock market — the daytime adventure serial of the well-to-do — would not be the stock market if it did not have its ups and downs. (...) And it has many other distinctive characteristics. Apart from the economic advantages and disadvantages of stock exchanges — the advantage that they provide a free flow of capital to finance industrial expansion, for instance, and the disadvantage that they provide an all too convenient way for the unlucky, the imprudent, and the gullible to lose their money — their development has created a whole pattern of social behavior, complete with customs, language, and predictable responses to given events. What is truly extraordinary is the speed with which this pattern emerged full blown following the establishment, in 1611, of the world's first important stock exchange — a roofless courtyard in Amsterdam — and the degree to which it persists (with variations, it is true) on the New York Stock Exchange in the nineteen-sixties. Present-day stock trading in the United States — a bewilderingly vast enterprise, involving millions of miles of private telegraph wires, computers that can read and copy the Manhattan Telephone Directory in three minutes, and over twenty million stockholder participants — would seem to be a far cry from a handful of seventeenth-century Dutchmen haggling in the rain. But the field marks are much the same. The first stock exchange was, inadvertently, a laboratory in which new human reactions were revealed. By the same token, the New York Stock Exchange is also a sociological test tube, forever contributing to the human species' self-understanding. The behaviour of the pioneering Dutch stock traders is ably documented in a book titled Confusion of Confusions, written by a plunger on the Amsterdam market named Joseph de la Vega; originally published in 1688, (...)

— John Brooks, in Business Adventures (1968)[72]

Even in the days before perestroika, socialism was never a monolith. Within the Communist countries, the spectrum of socialism ranged from the quasi-market, quasi-syndicalist system of Yugoslavia to the centralized totalitarianism of neighboring Albania. One time I asked Professor von Mises, the great expert on the economics of socialism, at what point on this spectrum of statism would he designate a country as "socialist" or not. At that time, I wasn't sure that any definite criterion existed to make that sort of clear-cut judgment. And so I was pleasantly surprised at the clarity and decisiveness of Mises's answer. "A stock market", he answered promptly. "A stock market is crucial to the existence of capitalism and private property. For it means that there is a functioning market in the exchange of private titles to the means of production. There can be no genuine private ownership of capital without a stock market: there can be no true socialism if such a market is allowed to exist."

— Murray Rothbard, in Making Economic Sense (2006)[73]

It is important to note that from about the early 1600s to about the mid-18th century, the Dutch Republic's economic, business and financial systems were the most advanced and sophisticated ever seen in history.[74][75][76][77] As Jacob Soll (2014) noted, "with the complexity of the stock exchange, [17th-century] Dutch merchants' knowledge of finance became more sophisticated than that of their Italian predecessors or German neighbors."[78] From about 1600 to about 1720 the Dutch had the highest per capita income in the world. The Dutch Golden Age's Tulip Mania (in the mid-1630s) is generally considered as the first recorded asset price bubble (also known as speculative bubble). Similarly, early stock market bubbles and crashes had their roots in socio-politico-economic activities of the 17th-century Dutch Republic (the birthplace of the world's first formal stock exchange and stock market),[79][75][80][81] the Dutch East India Company (the world's first formally listed public company) and the Dutch West India Company, in particular. At the dawn of modern capitalism, wherever Dutch capital went, urban features were developed, economic activities expanded, new industries established, new jobs created, trading companies operated, swamps drained, mines opened, forests exploited, canals constructed, mills turned, and ships were built.[26][82][27][34][35] In the early modern period, the Dutch were pioneering capitalists who raised the commercial and industrial potential of underdeveloped or undeveloped lands whose resources they exploited, whether for better or worse. For example, the native economies of pre-VOC-era Taiwan and South Africa were virtually undeveloped or were in almost primitive states. In other words, the recorded economic history of South Africa and Taiwan both began with the VOC period. It was VOC people who established and developed first urban areas in the history of Taiwan (Tainan) and South Africa (Cape Town and Stellenbosch).

Historically, the Dutch were responsible for at least four major pioneering institutional innovations[a] (in economic, business and financial history of the world):

- The foundation of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), the world's first publicly listed company[83][84] and the first historical model of the multinational corporation (or transnational corporation) in its modern sense,[b][85][86][87][88][89][90] in 1602. The birth of the VOC is often considered to be the official beginning of corporate-led globalization with the rise of modern corporations (multinational corporations in particular) as a highly significant socio-politico-economic force that affect human lives in every corner of the world today. As the first company to be listed on an official stock exchange, the VOC was the first company to issue stock and bonds to the general public. With its pioneering features, the VOC is generally considered a major institutional breakthrough and the model for modern corporations (large-scale business enterprises in particular). It is important to note that most of the largest and most influential companies of the modern-day world are publicly-traded multinational corporations, including Forbes Global 2000 companies. Like present-day publicly-listed multinational companies, in many ways, the post-1657 English/British East India Company's operational structure was a historical derivative of the earlier VOC model.[59][91]

- The establishment of the Amsterdam Stock Exchange (or Beurs van Hendrick de Keyser in Dutch), the world's first official stock exchange,[c] in 1611, along with the birth of the first fully functioning capital market in the early 1600s.[93] While the Italian city-states produced the first transferable government bonds, they didn't develop the other ingredient necessary to produce the fully fledged capital market in its modern sense: a formal stock market.[94][81][95] The Dutch were the firsts to use a fully fledged capital market (including the bond market and stock market) to finance public companies (such as the VOC and WIC). This was a precedent for the global securities market in its modern form. In the early 1600s the VOC established an exchange in Amsterdam where VOC stock and bonds could be traded in a secondary market. The establishment of the Amsterdam Stock Exchange (Beurs van Hendrick de Keyser) by the VOC, has long been recognized as the origin of modern-day stock exchanges[96][97] that specialize in creating and sustaining secondary markets in the securities issued by corporations. The process of buying and selling shares (of stock) in the VOC became the basis of the first formal stock market.[98][99] The Dutch pioneered stock futures, stock options, short selling, bear raids, debt-equity swaps, and other speculative instruments. Amsterdam businessman Joseph de la Vega's Confusion of Confusions (1688) was the earliest book about stock trading.[100]}}

- The establishment of the Bank of Amsterdam (Amsterdamsche Wisselbank), often considered to be the first historical model of the central bank,[101][102][103] in 1609. The birth of the Amsterdamsche Wisselbank led to the introduction of the concept of bank money. Along with a number of subsidiary local banks, it performed many functions of a central banking system.[104][105][106][107][108] It occupied a central position in the financial world of its day, providing an effective, efficient and trusted system for national and international payments, and introduced the first ever international reserve currency, the bank guilder.[109] Lucien Gillard calls it the European guilder (le florin européen),[110] and Adam Smith devotes many pages to explaining how the bank guilder works (Smith 1776: 446-455). The model of the Wisselbank as a state bank was adapted throughout Europe, including the Bank of Sweden (1668) and the Bank of England (1694).

- The formation of the first recorded professionally managed collective investment schemes (or investment funds), such as mutual funds,[111][76] in 1774. Amsterdam-based businessman Abraham van Ketwich (also known as Adriaan van Ketwich) is often credited as the originator of the world's first mutual fund. In response to the financial crisis of 1772–1773, Van Ketwich formed a trust named "Eendragt Maakt Magt" ("Unity Creates Strength"). His aim was to provide small investors with an opportunity to diversify.[111][112] Today the global funds industry is a multi-trillion-dollar business.

In many respects, the Dutch Republic's pioneering institutional innovations greatly helped revolutionize and shape the foundations of the economic and financial system of the modern-day world, and significantly influenced many English-speaking countries, especially the United Kingdom and United States.[113][24][114]

Other views[]

A competitor to the 'commercialization model' is the 'agrarian model',[citation needed] which explains the rise of capitalism by unique circumstances in English agrarianism. The evidence it cites is that traditional mercantilism focused on moving goods from markets where they were cheap to markets where they were expensive rather than investing in production, and that many cultures (including the early modern Dutch Republic) saw urbanisation and the amassing of wealth by merchants without the emergence of capitalist production.[115][116]

The agrarian argument developed particularly through Karl Polanyi's The Great Transformation (1944), Maurice Dobb's Studies in the Development of Capitalism (1946), and Robert Brenner's research in the 1970s, the discussion of which is known as the Brenner Debate. In the wake of the Norman Conquest, the English state was unusually centralised. This gave aristocrats relatively limited powers to extract wealth directly from their feudal underlings through political means (not least the threat of violence). England's centralisation also meant that an unusual number of English farmers were not peasants (with their own land and thus direct access to subsistence) but tenants (renting their land). These circumstances produced a market in leases. Landlords, lacking other ways to extract wealth, were motivated to rent to tenants who could pay the most, while tenants, lacking security of tenure, were motivated to farm as productively as possible to win leases in a competitive market. This led to a cascade of effects whereby successful tenant farmers became agrarian capitalists; unsuccessful ones became wage-labourers, required to sell their labour in order to live; and landlords promoted the privatisation and renting out of common land, not least through the enclosures. In this reading, 'it was not merchants or manufacturers who drove the process that propelled the early development of capitalism. The transformation of social property relations was firmly rooted in the countryside, and the transformation of England's trade and industry was result more than cause of England's transition to capitalism'.[117]

This article includes both perspectives.

21st-century developments[]

The 21st century has seen renewed interest in the history of capitalism, and "History of Capitalism" has become a field in its own right, with courses in history departments. In the 2000s, Harvard University founded the Program on the Study of U.S. Capitalism; Cornell University established the History of Capitalism Initiative;[118] and Columbia University Press launched a monograph series titled Studies in the History of U.S. Capitalism.[119] This field includes topics such as insurance, banking and regulation, the political dimension, and the impact on the middle classes, the poor and women and minorities.[120][121] These initiatives incorporate formerly neglected questions of race, gender, and sexuality into the history of capitalism. They have grown in the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2007–2008 and the associated Great Recession.

Some other academic institutions, such as the Clemson Institute for the Study of Capitalism, reject the notion that race, gender, or sexuality have any significant relationship to capitalism at all and instead seek to show that laissez-faire capitalism, in particular, provides the best and most numerous economic opportunities for all people.[122]

Agrarian capitalism[]

Crisis of the 14th century[]

William R. Shepherd, Historical Atlas, 01923

According to some historians,[123] the modern capitalist system originated in the "crisis of the Late Middle Ages", a conflict between the land-owning aristocracy and the agricultural producers, or serfs. Manorial arrangements inhibited the development of capitalism in a number of ways. Serfs had obligations to produce for lords and therefore had no interest in technological innovation; they also had no interest in cooperating with one another because they produced to sustain their own families. The lords who owned the land[citation needed] relied on force to guarantee that they received sufficient food. Because lords were not producing to sell on the market, there was no competitive pressure for them to innovate. Finally, because lords expanded their power and wealth through military means, they spent their wealth on military equipment or on conspicuous consumption that helped foster alliances with other lords; they had no incentive to invest in developing new productive technologies.[124]

The demographic crisis of the 14th century upset this arrangement. This crisis had several causes: agricultural productivity reached its technological limitations and stopped growing, bad weather led to the Great Famine of 1315–1317, and the Black Death of 1348–1350 led to a population crash. These factors led to a decline in agricultural production. In response, feudal lords sought to expand agricultural production by extending their domains through warfare; therefore they demanded more tribute from their serfs to pay for military expenses. In England, many serfs rebelled. Some moved to towns, some bought land, and some entered into favorable contracts to rent lands from lords who needed to repopulate their estates.[125]

The collapse of the manorial system in England enlarged the class of tenant farmers with more freedom to market their goods and thus more incentive to invest in new technologies. Lords who did not want to rely on renters could buy out or evict tenant farmers, but then had to hire free labor to work their estates, giving them an incentive to invest in two kinds of commodity owners. One kind was those who had money, the means of production, and subsistence, who were eager to valorize the sum of value they had appropriated by buying the labor power of others.[citation needed] The other kind was free workers, who sold their own labor. The workers neither formed part of the means of production nor owned the means of production that transformed land and even money into what we now call "capital".[126] Marx labeled this period the "pre-history of capitalism".[127]

In effect, feudalism began to lay some of the foundations necessary for the development of mercantilism, a precursor of capitalism. Feudalism was mostly confined to Europe[citation needed] and lasted from the medieval period through the 16th century. Feudal manors were almost entirely self-sufficient, and therefore limited the role of the market. This stifled any incipient tendency towards capitalism. However, the relatively sudden emergence of new technologies and discoveries, particularly in agriculture[128] and exploration, facilitated the growth of capitalism. The most important development at the end of feudalism[citation needed] was the emergence of what Robert Degan calls "the dichotomy between wage earners and capitalist merchants".[129] The competitive nature meant there are always winners and losers, and this became clear as feudalism evolved into mercantilism, an economic system characterized by the private or corporate ownership of capital goods, investments determined by private decisions, and by prices, production, and the distribution of goods determined mainly by competition in a free market.[citation needed]

Enclosure[]

England in the 16th century was already a centralized state, in which much of the feudal order of Medieval Europe had been swept away. This centralization was strengthened by a good system of roads and a disproportionately large capital city, London.[130] The capital acted as a central market for the entire country, creating a large internal market for goods, in contrast to the fragmented feudal holdings that prevailed in most parts of the Continent. The economic foundations of the agricultural system were also beginning to diverge substantially; the manorial system had broken down by this time, and land began to be concentrated in the hands of fewer landlords with increasingly large estates. The system put pressure on both the landlords and the tenants to increase agricultural productivity to create profit. The weakened coercive power of the aristocracy to extract peasant surpluses encouraged them to try out better methods. The tenants also had an incentive to improve their methods to succeed in an increasingly competitive labour market. Land rents had moved away from the previous stagnant system of custom and feudal obligation, and were becoming directly subject to economic market forces.

An important aspect of this process of change was the enclosure[131] of the common land previously held in the open field system where peasants had traditional rights, such as mowing meadows for hay and grazing livestock. Once enclosed, these uses of the land became restricted to the owner, and it ceased to be land for commons. The process of enclosure began to be a widespread feature of the English agricultural landscape during the 16th century. By the 19th century, unenclosed commons had become largely restricted to rough pasture in mountainous areas and to relatively small parts of the lowlands.

Marxist and neo-Marxist historians argue that rich landowners used their control of state processes to appropriate public land for their private benefit. This created a landless working class that provided the labour required in the new industries developing in the north of England. For example: "In agriculture the years between 1760 and 1820 are the years of wholesale enclosure in which, in village after village, common rights are lost".[132] "Enclosure (when all the sophistications are allowed for) was a plain enough case of class robbery".[133] Anthropologist Jason Hickel notes that this process of enclosure led to myriad peasant revolts, among them Kett's Rebellion and the Midland Revolt, which culminated in violent repression and executions.[134]

Other scholars[135] argue that the better-off members of the European peasantry encouraged and participated actively in enclosure, seeking to end the perpetual poverty of subsistence farming. "We should be careful not to ascribe to [enclosure] developments that were the consequence of a much broader and more complex process of historical change."[136] "[T]he impact of eighteenth and nineteenth century enclosure has been grossly exaggerated...."[137]

Merchant capitalism and mercantilism[]

Precedents[]

While trade has existed since early in human history, it was not capitalism.[138] The earliest recorded activity of long-distance profit-seeking merchants can be traced to the Old Assyrian merchants active in Mesopotamia the 2nd millennium BCE.[139] The Roman Empire developed more advanced forms of commerce, and similarly widespread networks existed in Islamic nations. However, capitalism took shape in Europe in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance.

An early emergence of commerce occurred on monastic estates in Italy and France and in the independent city republics of Italy during the late Middle Ages. Innovations in banking, insurance, accountancy, and various production and commercial practices linked closely to a 'spirit' of frugality, reinvestment, and city life, promoted attitudes that sociologists have tended to associate only with northern Europe, Protestantism, and a much later age. The city republics maintained their political independence from Empire and Church, traded with North Africa, the Middle East and Asia, and introduced Eastern practices. They were also considerably different from the absolutist monarchies of Spain and France, and were strongly attached to civic liberty.[140][141][142]

Emergence[]

Modern capitalism only fully emerged in the early modern period between the 16th and 18th centuries, with the establishment of mercantilism or merchant capitalism.[143][144] Early evidence for mercantilistic practices appears in early modern Venice, Genoa, and Pisa over the Mediterranean trade in bullion. The region of mercantilism's real birth, however, was the Atlantic Ocean.[145]

England began a large-scale and integrative approach to mercantilism during the Elizabethan Era. An early statement on national balance of trade appeared in Discourse of the Common Weal of this Realm of England, 1549: "We must always take heed that we buy no more from strangers than we sell them, for so should we impoverish ourselves and enrich them."[146][full citation needed] The period featured various but often disjointed efforts by the court of Queen Elizabeth to develop a naval and merchant fleet capable of challenging the Spanish stranglehold on trade and of expanding the growth of bullion at home. Elizabeth promoted the Trade and Navigation Acts in Parliament and issued orders to her navy for the protection and promotion of English shipping.

These efforts organized national resources sufficiently in the defense of England against the far larger and more powerful Spanish Empire, and in turn paved the foundation for establishing a global empire in the 19th century.[citation needed] The authors noted most for establishing the English mercantilist system include Gerard de Malynes and Thomas Mun, who first articulated the . The latter's England's Treasure by Forraign Trade, or the Balance of our Forraign Trade is The Rule of Our Treasure gave a systematic and coherent explanation of the concept of balance of trade. It was written in the 1620s and published in 1664.[147] Mercantile doctrines were further developed by Josiah Child. Numerous French authors helped to cement French policy around mercantilism in the 17th century. French mercantilism was best articulated by Jean-Baptiste Colbert (in office, 1665–1683), although his policies were greatly liberalised under Napoleon.

Doctrines[]

Under mercantilism, European merchants, backed by state controls, subsidies, and monopolies, made most of their profits from buying and selling goods. In the words of Francis Bacon, the purpose of mercantilism was "the opening and well-balancing of trade; the cherishing of manufacturers; the banishing of idleness; the repressing of waste and excess by sumptuary laws; the improvement and husbanding of the soil; the regulation of prices..."[148] Similar practices of economic regimentation had begun earlier in medieval towns. However, under mercantilism, given the contemporaneous rise of absolutism, the state superseded the local guilds as the regulator of the economy.

Among the major tenets of mercantilist theory was bullionism, a doctrine stressing the importance of accumulating precious metals. Mercantilists argued that a state should export more goods than it imported so that foreigners would have to pay the difference in precious metals. Mercantilists asserted that only raw materials that could not be extracted at home should be imported. They promoted the idea that government subsidies, such as granting monopolies and protective tariffs, were necessary to encourage home production of manufactured goods.

Proponents of mercantilism emphasized state power and overseas conquest as the principal aim of economic policy. If a state could not supply its own raw materials, according to the mercantilists, it should acquire colonies from which they could be extracted. Colonies constituted not only sources of raw materials but also markets for finished products. Because it was not in the interests of the state to allow competition, to help the mercantilists, colonies should be prevented from engaging in manufacturing and trading with foreign powers.

Mercantilism was a system of trade for profit, although commodities were still largely produced by non-capitalist production methods.[3] Noting the various pre-capitalist features of mercantilism, Karl Polanyi argued that "mercantilism, with all its tendency toward commercialization, never attacked the safeguards which protected [the] two basic elements of production – labor and land – from becoming the elements of commerce." Thus mercantilist regulation was more akin to feudalism than capitalism. According to Polanyi, "not until 1834 was a competitive labor market established in England, hence industrial capitalism as a social system cannot be said to have existed before that date."[149]

Chartered trading companies[]

The Muscovy Company was the first major chartered joint stock English trading company. It was established in 1555 with a monopoly on trade between England and Muscovy. It was an offshoot of the earlier Company of Merchant Adventurers to New Lands, founded in 1551 by Richard Chancellor, Sebastian Cabot and Sir Hugh Willoughby to locate the Northeast Passage to China to allow trade. This was the precursor to a type of business that would soon flourish in England, the Dutch Republic and elsewhere.

The British East India Company (1600) and the Dutch East India Company (1602) launched an era of large state chartered trading companies.[20][150] These companies were characterized by their monopoly on trade, granted by letters patent provided by the state. Recognized as chartered joint-stock companies by the state, these companies enjoyed lawmaking, military, and treaty-making privileges.[151] Characterized by its colonial and expansionary powers by states, powerful nation-states sought to accumulate precious metals, and military conflicts arose.[20] During this era, merchants, who had previously traded on their own, invested capital in the East India Companies and other colonies, seeking a return on investment.

Industrial capitalism[]

Mercantilism declined in Great Britain in the mid-18th century, when a new group of economic theorists, led by Adam Smith, challenged fundamental mercantilist doctrines, such as that the world's wealth remained constant and that a state could only increase its wealth at the expense of another state. However, mercantilism continued in less developed economies, such as Prussia and Russia, with their much younger manufacturing bases.

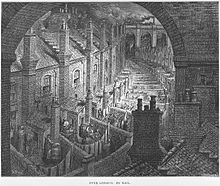

The mid-18th century gave rise to industrial capitalism, made possible by (1) the accumulation of vast amounts of capital under the merchant phase of capitalism and its investment in machinery, and (2) the fact that the enclosures meant that Britain had a large population of people with no access to subsistence agriculture, who needed to buy basic commodities via the market, ensuring a mass consumer market.[152] Industrial capitalism, which Marx dated from the last third of the 18th century, marked the development of the factory system of manufacturing, characterized by a complex division of labor between and within work processes and the routinization of work tasks. Industrial capitalism finally established the global domination of the capitalist mode of production.[143]

During the resulting Industrial Revolution, the industrialist replaced the merchant as a dominant actor in the capitalist system, which led to the decline of the traditional handicraft skills of artisans, guilds, and journeymen. Also during this period, capitalism transformed relations between the British landowning gentry and peasants, giving rise to the production of cash crops for the market rather than for subsistence on a feudal manor. The surplus generated by the rise of commercial agriculture encouraged increased mechanization of agriculture.

Industrial Revolution[]

The productivity gains of capitalist production began a sustained and unprecedented increase at the turn of the 19th century, in a process commonly referred to as the Industrial Revolution. Starting in about 1760 in England, there was a steady transition to new manufacturing processes in a variety of industries, including going from hand production methods to machine production, new chemical manufacturing and iron production processes, improved efficiency of water power, the increasing use of steam power and the development of machine tools. It also included the change from wood and other bio-fuels to coal.

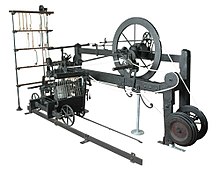

In textile manufacturing, mechanized cotton spinning powered by steam or water increased the output of a worker by a factor of about 1000, due to the application of James Hargreaves' spinning jenny, Richard Arkwright's water frame, Samuel Crompton's Spinning Mule and other inventions. The power loom increased the output of a worker by a factor of over 40.[153] The cotton gin increased the productivity of removing seed from cotton by a factor of 50. Large gains in productivity also occurred in spinning and weaving wool and linen, although they were not as great as in cotton.

Finance[]

The growth of Britain's industry stimulated a concomitant growth in its system of finance and credit. In the 18th century, services offered by banks increased. Clearing facilities, security investments, cheques and overdraft protections were introduced. Cheques had been invented in the 17th century in England, and banks settled payments by direct courier to the issuing bank. Around 1770, they began meeting in a central location, and by the 19th century a dedicated space was established, known as a bankers' clearing house. The London clearing house used a method where each bank paid cash to and then was paid cash by an inspector at the end of each day. The first overdraft facility was set up in 1728 by The Royal Bank of Scotland.

The end of the Napoleonic War and the subsequent rebound in trade led to an expansion in the bullion reserves held by the Bank of England, from a low of under 4 million pounds in 1821 to 14 million pounds by late 1824.

Older innovations became routine parts of financial life during the 19th century. The Bank of England first issued bank notes during the 17th century, but the notes were hand written and few in number. After 1725, they were partially printed, but cashiers still had to sign each note and make them payable to a named person. In 1844, parliament passed the Bank Charter Act tying these notes to gold reserves, effectively creating the institution of central banking and monetary policy. The notes became fully printed and widely available from 1855.[citation needed]

Growing international trade increased the number of banks, especially in London. These new "merchant banks" facilitated trade growth, profiting from England's emerging dominance in seaborne shipping. Two immigrant families, Rothschild and Baring, established merchant banking firms in London in the late 18th century and came to dominate world banking in the next century. The tremendous wealth amassed by these banking firms soon attracted much attention. The poet George Gordon Byron wrote in 1823: "Who makes politics run glibber all?/ The shade of Bonaparte's noble daring?/ Jew Rothschild and his fellow-Christian, Baring."

The operation of banks also shifted. At the beginning of the century, banking was still an elite preoccupation of a handful of very wealthy families. Within a few decades, however, a new sort of banking had emerged, owned by anonymous stockholders, run by professional managers, and the recipient of the deposits of a growing body of small middle-class savers. Although this breed of banks was newly prominent, it was not new – the Quaker family Barclays had been banking in this way since 1690.

Free trade and globalization[]

At the height of the First French Empire, Napoleon sought to introduce a "continental system" that would render Europe economically autonomous, thereby emasculating British trade and commerce. It involved such stratagems as the use of beet sugar in preference to the cane sugar that had to be imported from the tropics. Although this caused businessmen in England to agitate for peace, Britain persevered, in part because it was well into the industrial revolution. The war had the opposite effect – it stimulated the growth of certain industries, such as pig-iron production which increased from 68,000 tons in 1788 to 244,000 by 1806.[citation needed]

In 1817, David Ricardo, James Mill and Robert Torrens, in the famous theory of comparative advantage, argued that free trade would benefit the industrially weak as well as the strong. In Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, Ricardo advanced the doctrine still considered the most counterintuitive in economics:

- When an inefficient producer sends the merchandise it produces best to a country able to produce it more efficiently, both countries benefit.

By the mid 19th century, Britain was firmly wedded to the notion of free trade, and the first era of globalization began.[143] In the 1840s, the Corn Laws and the Navigation Acts were repealed, ushering in a new age of free trade. In line with the teachings of the classical political economists, led by Adam Smith and David Ricardo, Britain embraced liberalism, encouraging competition and the development of a market economy.

Industrialization allowed cheap production of household items using economies of scale,[citation needed] while rapid population growth created sustained demand for commodities. Nineteenth-century imperialism decisively shaped globalization in this period. After the First and Second Opium Wars and the completion of the British conquest of India, vast populations of these regions became ready consumers of European exports. During this period, areas of sub-Saharan Africa and the Pacific islands were incorporated into the world system. Meanwhile, the European conquest of new parts of the globe, notably sub-Saharan Africa, yielded valuable natural resources such as rubber, diamonds and coal and helped fuel trade and investment between the European imperial powers, their colonies, and the United States.[154]

The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea, the various products of the whole earth, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep. Militarism and imperialism of racial and cultural rivalries were little more than the amusements of his daily newspaper. What an extraordinary episode in the economic progress of man was that age which came to an end in August 1914.

The global financial system was mainly tied to the gold standard during this period. The United Kingdom first formally adopted this standard in 1821. Soon to follow was Canada in 1853, Newfoundland in 1865, and the United States and Germany (de jure) in 1873. New technologies, such as the telegraph, the transatlantic cable, the Radiotelephone, the steamship, and the railway allowed goods and information to move around the world at an unprecedented degree.[155]

The eruption of civil war in the United States in 1861 and the blockade of its ports to international commerce meant that the main supply of cotton for the Lancashire looms was cut off. The textile industries shifted to reliance upon cotton from Africa and Asia during the course of the U.S. civil war, and this created pressure for an Anglo-French controlled canal through the Suez peninsula. The Suez canal opened in 1869, the same year in which the Central Pacific Railroad that spanned the North American continent was completed. Capitalism and the engine of profit were making the globe a smaller place.

Benefits to workers[]

Prior to the rise of industrial capitalism, the vast majority of the world population were subsistence farmers, hunters, or gatherers for whom famine and disease were constant threats. Industrialization brought about divisions of labor, improved sanitation, dramatically increased free time, rising wages, and falling demand for dangerous farm work, all of which contributed to tremendous improvements in health and longevity for early industrial workers, despite the hazardous conditions in some primitive factories.[156] Average life expectancy in Europe and America was 34–35 years in 1800; this number had risen to 68 years by 1950.[157]

20th century[]

Several major challenges to capitalism appeared in the early part of the 20th century. The Russian revolution in 1917 established the first socialist state in the world; a decade later, the Great Depression triggered increasing criticism of the existing capitalist system. One response to this crisis was a turn to fascism, an ideology that advocated state capitalism.[158] Another response was to reject capitalism altogether in favor of communist or socialist ideologies.

Keynesianism and free markets[]

The economic recovery of the world's leading capitalist economies in the period following the end of the Great Depression and the Second World War—a period of unusually rapid growth by historical standards—eased discussion of capitalism's eventual decline or demise.[159] The state began to play an increasingly prominent role to moderate and regulate the capitalistic system throughout much of the world.

Keynesian economics became a widely accepted method of government regulation and countries such as the United Kingdom experimented with mixed economies in which the state owned and operated certain major industries.

The state also expanded in the US; in 1929, total government expenditures amounted to less than one-tenth of GNP; from the 1970s they amounted to around one-third.[144] Similar increases were seen in all industrialized capitalist economies, some of which, such as France, have reached even higher ratios of government expenditures to GNP than the United States.

A broad array of new analytical tools in the social sciences were developed to explain the social and economic trends of the period, including the concepts of post-industrial society and the welfare state.[143]

The long postwar boom ended in the 1970s, amid the economic crises experienced following the 1973 oil crisis.[160] The "stagflation" of the 1970s led many economic commentators and politicians to embrace market-oriented policy prescriptions inspired by the laissez-faire capitalism and classical liberalism of the 19th century, particularly under the influence of Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman. The theoretical alternative to Keynesianism was more compatible with laissez-faire and emphasized rapid expansion of the economy. Market-oriented solutions gained increasing support in the capitalist world, especially under leadership of Ronald Reagan in the U.S. and Margaret Thatcher in the UK in the 1980s. Public and political interest began shifting away from the so-called collectivist concerns of Keynes's managed capitalism to a focus on individual choice, called "remarketized capitalism".[161]

Globalization[]

Although overseas trade has been associated with the development of capitalism for over five hundred years, some thinkers argue that a number of trends associated with globalization have acted to increase the mobility of people and capital since the last quarter of the 20th century, combining to circumscribe the room to maneuver of states in choosing non-capitalist models of development. Today, these trends have bolstered the argument that capitalism should now be viewed as a truly world system (Burnham). However, other thinkers argue that globalization, even in its quantitative degree, is no greater now than during earlier periods of capitalist trade.[162]

After the abandonment of the Bretton Woods system in 1971, and the strict state control of foreign exchange rates, the total value of transactions in foreign exchange was estimated to be at least twenty times greater than that of all foreign movements of goods and services (EB). The internationalization of finance, which some see as beyond the reach of state control, combined with the growing ease with which large corporations have been able to relocate their operations to low-wage states, has posed the question of the 'eclipse' of state sovereignty, arising from the growing 'globalization' of capital.[163]

While economists generally agree about the size of global income inequality[citation needed], there is a general disagreement about the recent direction of change of it.[164] In cases such as China, where income inequality is clearly growing[165] it is also evident that overall economic growth has rapidly increased with capitalist reforms.[166] The book The Improving State of the World, published by the libertarian think tank Cato Institute, argues that economic growth since the Industrial Revolution has been very strong and that factors such as adequate nutrition, life expectancy, infant mortality, literacy, prevalence of child labor, education, and available free time have improved greatly.[167] Some scholars, including Stephen Hawking[168] and researchers for the International Monetary Fund,[169][170] contend that globalization and neoliberal economic policies are not ameliorating inequality and poverty but exacerbating it,[171][172][173] and are creating new forms of contemporary slavery.[174][175] Such policies are also expanding populations of the displaced, the unemployed and the imprisoned[176][177] along with accelerating the destruction of the environment[171] and species extinction.[178][179] In 2017, the IMF warned that inequality within nations, in spite of global inequality falling in recent decades, has risen so sharply that it threatens economic growth and could result in further political polarization.[180] Surging economic inequality following the economic crisis and the anger associated with it have resulted in a resurgence of socialist and nationalist ideas throughout the Western world, which has some economic elites from places including Silicon Valley, Davos and Harvard Business School concerned about the future of capitalism.[181]

Today[]

By the beginning of the 21st century, mixed economies with capitalist elements had become the pervasive economic systems worldwide. The collapse of the Soviet bloc in 1991 significantly reduced the influence of Socialism as an alternative economic system. Socialist movements continue to be influential in some parts of the world, most notably Latin-American Bolivarianism, with some having ties to more traditional anti-capitalist movements, such as Bolivarian Venezuela's ties to communist Cuba.

In many emerging markets, the influence of banking and financial capital have come to increasingly shape national developmental strategies, leading some to argue we are in a new phase of financial capitalism.[182]

State intervention in global capital markets following the financial crisis of 2007–2010 was perceived by some as signaling a crisis for free-market capitalism. Serious turmoil in the banking system and financial markets due in part to the subprime mortgage crisis reached a critical stage during September 2008, characterized by severely contracted liquidity in the global credit markets posed an existential threat to investment banks and other institutions.[183][184]

Future[]

According to some,[who?][185] the transition to the information society involves abandoning some parts of capitalism, as the "capital" required to produce and process information becomes available to the masses and difficult to control, and is closely related to the controversial issues of intellectual property. Some[185] even speculate that the development of mature nanotechnology, particularly of universal assemblers, may make capitalism obsolete, with capital ceasing to be an important factor in the economic life of humanity. Various thinkers have also explored what kind of economic system might replace capitalism, such as Bob Avakian and Paul Mason.

Role of women[]

Women's historians have debated the impact of capitalism on the status of women.[186][187] Alice Clark argues that, when capitalism arrived in 17th-century England, it negatively impacted the status of women, who lost much of their economic importance. Clark argues that, in 16th-century England, women were engaged in many aspects of industry and agriculture. The home was a central unit of production, and women played a vital role in running farms and in some trades and landed estates. Their useful economic roles gave them a sort of equality with their husbands. However, Clark argues, as capitalism expanded in the 17th century, there was more and more division of labor, with the husband taking paid labor jobs outside the home, and the wife reduced to unpaid household work. Middle-class women were confined to an idle domestic existence, supervising servants; lower-class women were forced to take poorly paid jobs. Capitalism, therefore, had a negative effect on women.[188] By contrast, Ivy Pinchbeck argues that capitalism created the conditions for women's emancipation.[189] Tilly and Scott have emphasized the continuity and the status of women, finding three stages in European history. In the preindustrial era, production was mostly for home use, and women produced many household needs. The second stage was the "family wage economy" of early industrialization. During this stage, the entire family depended on the collective wages of its members, including husband, wife, and older children. The third, or modern, stage is the "family consumer economy", in which the family is the site of consumption, and women are employed in large numbers in retail and clerical jobs to support rising standards of consumption.[190]

Other writers and historians point out that capitalism's decentralized nature has led to increased autonomy for all people, including women.[191]

See also[]

- Brenner debate

- Capitalism and Islam

- Capitalist mode of production

- Enclosure and British Agricultural Revolution

- Fernand Braudel

- Financial crisis of 2007–2008

- History of capitalist theory

- History of globalization

- History of private equity and venture capital

- Primitive accumulation of capital

- Protestant work ethic

- Simple commodity production

Notes[]

- ^ Inventions and innovations whose earliest known fully functioning historical models were first effectively institutionalized and operated by the peoples of the Netherlands.

- ^ It is important to note the difference between a "corporation" and a "company" in general, hence the difference between a "multinational corporation" and a "multinational company" in its modern sense.

- ^ The concept of the bourse (or the exchange) was 'invented' in the medieval Low Countries, most notably in predominantly Dutch-speaking cities like Bruges and Antwerp, before the birth of formal stock exchanges in the 17th century. From Flemish cities the term 'beurs' spread to other European states where it was corrupted into 'bourse', 'borsa', 'bolsa', 'börse', etc. In Britain, too, the term 'bourse' was used between 1550 and 1775, eventually giving way to the term 'royal exchange'. Until the early 1600s, a bourse was not exactly a stock exchange in its modern sense. With the founding of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in 1602 and the rise of Dutch capital markets in the early 17th century, the 'old' bourse (a place to trade commodities, government and municipal bonds) found a new purpose – a formal exchange that specialize in creating and sustaining secondary markets in the securities (such as bonds and shares of stock) issued by corporations – or a stock exchange as we know it today.[92]

References[]

- ^ Compare: Rogers, Alisdair; Castree, Noel; Kitchin, Rob (2013). "capitalism". A Dictionary of Human Geography. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-959986-8. Retrieved 2019-08-11.

Capitalism is the world's dominant economic system but was virtually non-existent three hundred years ago.

- ^ Calhoun, Craig (2002). "capitalism". Dictionary of the Social Sciences. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512371-5. Retrieved 2019-08-11.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Scott, John; Marshall, Gordon (2005). "capitalism". Oxford Dictionary of Sociology (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860986-5.

- ^ "Elizabeth Warren's Theory of Capitalism". 28 August 2018.

- ^ Agrarian Capitalism in Theory and Practice. UNC Press Books. 10 October 2017. ISBN 9781469639727.

- ^ https://www.commongoodcapitalism.org/

- ^ "Marco Rubio's "Common Good Capitalism" is Just What We Need".

- ^ Harman, Chris (2010). Zombie Capitalism. Chicago: Haymarket. pp. 143–160. ISBN 978-1-60846-104-2. Retrieved 2019-08-11.

- ^ Marois, Thomas (2012) "Finance, Finance Capital, and Financialisation". In: Fine, Ben and Saad Filho, Alfredo, (eds.), The Elgar Companion to Marxist Economics. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- ^ "Monthly Review | the Necessity of Gangster Capitalism". February 2000.

- ^ Gavin Kelly, Dominic Kelly and Andrew Gamble, Stakeholder Capitalism ( New York: St. Martin's Press, 1997), ISBN 0333687744.

- ^ R. Edward Freeman, Kirsten Martin and Bidhan Parmar, 'Stakeholder Capitalism', Journal of Business Ethics, 74 (2007), 303–14 doi:10.1007/s10551-007-9517-y.

- ^ R. Edward Freeman and others, Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), ISBN 9780521190817.

- ^ Brown, Michael Barratt (1974). The economics of imperialism. Penguin Education. pp. 309–330.

- ^ Harman, Chris (1999). A People's History of the World. London: Bookmarks. pp. 251–397. ISBN 978-1-898876-55-7.

- ^ Galbraith, John Kenneth (2007). The New Industrial State (1st Princeton ed.). Princeton University Press. pp. 25–41. ISBN 978-0-691-13141-2.

- ^ Richard Biernacki, review of Ellen Meiksins Wood (1999), The Origin of Capitalism (Monthly Review Press, 1999), in Contemporary Sociology, Vol. 29, No. 4 (Jul., 2000), pp. 638–39 JSTOR 2654574.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ellen Meiksins Wood (2002), The Origin of Capitalism: A Longer View (London: Verso, 2002).

- ^ Ellen Meiksins Wood (2002), The Origin of Capitalism: A Longer View (London: Verso, 2002.), pp. 11–21.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Jairus Banaji (2007), "Islam, the Mediterranean and the rise of capitalism", Journal Historical Materialism 15#1 pp. 47–74, Brill Publishers.

- ^ Neal, Larry: The Rise of Financial Capitalism: International Capital Markets in the Age of Reason (Studies in Monetary and Financial History). (Cambridge University Press, 1993, ISBN 9780521457385)

- ^ Goetzmann, William N.; Rouwenhorst, K. Geert: The Origins of Value: The Financial Innovations that Created Modern Capital Markets. (Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0195175714))

- ^ Rothbard, Murray: Making Economic Sense, 2nd edition. (Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2006, ISBN 9781610165907), p. 426

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dore, Ronald: Stock Market Capitalism, Welfare Capitalism: Japan and Germany versus the Anglo-Saxons. (Oxford University Press, 2000) ISBN 978-0199240616

- ^ Preda, Alex: Framing Finance: The Boundaries of Markets and Modern Capitalism. (University of Chicago Press, 2009, pp. 328, ISBN 978-0-226-67932-7)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brenner, Reuven (1994). Labyrinths of Prosperity: Economic Follies, Democratic Remedies. (University of Michigan Press, 1994), p. 57-60

- ^ Jump up to: a b Moore, Jason W. (2010b). "'Amsterdam is Standing on Norway' Part II: The Global North Atlantic in the Ecological Revolution of the Long Seventeenth Century", Journal of Agrarian Change, 10, 2, p. 188–227

- ^ Chen, Piera; Gardner, Dinah: Lonely Planet: Taiwan [10th edition]. (Lonely Planet, 2017, ISBN 978-1786574398).

- ^ Shih, Chih-Ming; Yen, Szu-Yin (2009). The Transformation of the Sugar Industry and Land Use Policy in Taiwan, in Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering [8:1], pp. 41–48

- ^ Tseng, Hua-pi (2016). Sugar Cane and the Environment under Dutch Rule in Seventeenth Century Taiwan, in Environmental History in the Making, pp. 189–200

- ^ Estreicher, Stefan K. (2014), 'A Brief History of Wine in South Africa,'. European Review 22(3): pp. 504–537. doi:10.1017/S1062798714000301

- ^ Fourie, Johan; von Fintel, Dieter (2014), 'Settler Skills and Colonial Development: The Huguenot Wine-Makers in Eighteenth-Century Dutch South Africa,'. The Economic History Review 67(4): 932–963. doi:10.1111/1468-0289.12033

- ^ Thompson, Laurence G. (1964), 'The Earliest Chinese Eyewitness Accounts of the Formosan Aborigines,'. Monumenta Serica 23(1): 163–204. Laurence G. Thompson (1964) noted, "The most striking fact about the historical knowledge of Formosa is the lack of it in Chinese records. It is truly astonishing that this very large island, so close to the mainland that on exceptionally clear days it may be made out from certain places on the Fukien coast with the unaided eye, should have remained virtually beyond the ken of Chinese writers down until late Ming times (seventeenth century)."

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Lindblad, J. Thomas (1995), 'Louis de Geer (1587–1652): Dutch Entrepreneur and the Father of Swedish Industry,'; in Clé Lesger & Leo Noordegraaf (eds.), Entrepreneurs and Entrepreneurship in Early Modern Times: Merchants and Industrialists within the Orbit of the Dutch Staple Markets. (The Hague: Stichting Hollandse Historische Reeks, 1995), pp. 77–85

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Müller, Leos (2005), 'The Dutch Entrepreneurial Networks and Sweden in the Age of Greatness,'; in Hanno Brand (ed.), Trade, Diplomacy and Cultural Exchange: Continuity and Change in the North Sea Area and the Baltic, c. 1350–1750. (Hilversum: Verloren, 2005), pp. 58–74

- ^ Neal, Larry: The Rise of Financial Capitalism: International Capital Markets in the Age of Reason. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993)

- ^ Neal, Larry (2005), 'Venture Shares of the Dutch East India Company,'; in William N. Goetzmann & K. Geert Rouwenhorst (eds.), The Origins of Value: The Financial Innovations that Created Modern Capital Markets. (Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 165–175

- ^ Neal, Larry; Atack, Jeremy (eds.): The Origins and Development of Financial Markets and Institutions: From the Seventeenth Century to the Present. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009)

- ^ Brook, Timothy: Vermeer's Hat: The Seventeenth Century and the Dawn of the Global World. (Profile Books, 2008, ISBN 1-84668-120-0)

- ^ Zahedieh, Nuala (2010). The Capital and the Colonies: London and the Atlantic Economy 1660–1700 (Cambridge University Press), p. 152

- ^ Kaiser, Kevin; Young, S. David: The Blue Line Imperative: What Managing for Value Really Means. (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2013) ISBN 978-1118510889, p. 26

- ^ Funnell, Warwick; Robertson, Jeffrey: Accounting by the First Public Company: The Pursuit of Supremacy. (New York: Routledge, 2014, ISBN 0415716179)

- ^ Gelderloos, Peter: Worshipping Power: An Anarchist View of Early State Formation. (Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2016)

- ^ Moore, Jason W. (20 December 2017). "World accumulation & Planetary life, or, why capitalism will not survive until the 'last tree is cut'". Political Economy Research Centre, Goldsmiths, University of London (perc.org.uk). Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- ^ Barbour, Violet: Capitalism in Amsterdam in the Seventeenth Century. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1950)

- ^ Murray, James M.: Bruges: Cradle of Capitalism, 1280–1390. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005)

- ^ Van der Wee, Herman: The Growth of the Antwerp Market and the European Economy [3 vols.]. (The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1963)

- ^ Voet, Leon: Antwerp, the Golden Age: The Rise and Glory of the Metropolis in the Sixteenth Century. (Antwerp: Mercatorfonds, 1973)

- ^ Gelderblom, Oscar: Cities of Commerce: The Institutional Foundations of International Trade in the Low Countries, 1250–1650. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0-691-14288-3)

- ^ Puttevils, Jeroen: Merchants and Trading in the Sixteenth Century: The Golden Age of Antwerp. (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2015)

- ^ Karl Marx described the Dutch Republic, in its Golden Age, as "the model capitalist nation of the seventeenth century", which was in "the rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production". He concluded that "its [Dutch Republic's] fisheries, marine, manufactures, surpassed those of any other country. The total capital of the Republic was probably more important than that of all the rest of Europe put together."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wallerstein, Immanuel: The Modern World-System II: Mercantilism and the Consolidation of the European World-Economy, 1600–1750. (Academic Press, 1980)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bornschier, Volker; Lengyel, Peter (1992). Waves, Formations and Values in the World System, p. 69. "The rise of capitalist national states (as opposed to city-states) was a European innovation, and the first of these was the Dutch Republic of the seventeenth century."

- ^ Brenner, Reuven (1994). Labyrinths of Prosperity: Economic Follies, Democratic Remedies, p. 60

- ^ De Vries, Jan; Woude, Ad van der (1997). The First Modern Economy: Success, Failure, and Perseverance of the Dutch Economy, 1500–1815

- ^ Jump up to: a b Taylor, Peter J. (2002). Dutch Hegemony and Contemporary Globalization (Paper prepared for Political Economy of World-Systems Conference, Riverside, California). As Peter J. Taylor notes, "the Dutch developed a social formula, which we have come to call modern capitalism, that proved to be transferable and ultimately deadly to all other social formulations."

- ^ Gordon, John Steele (1999). The Great Game: The Emergence of Wall Street as a World Power: 1653–2000. (Scribner, ISBN 978-0684832876). John Steele Gordon notes: "The Dutch invented modern capitalism in the early seventeenth century. Although many of the basic concepts had first appeared in Italy during the Renaissance, the Dutch, especially the citizens of the city of Amsterdam, were the real innovators. They transformed banking, stock exchanges, credit, insurance, and limited-liability corporations into a coherent financial and commercial system."

- ^ Gordon, Scott (1999). Controlling the State: Constitutionalism from Ancient Athens to Today, p. 172. As Scott Gordon notes: "In addition to its role in the history of constitutionalism, the republic was important in the early development of the essential features of modern capitalism: private property, production for sale in general markets, and the dominance of the profit motive in the behavior of producers and traders."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sayle, Murray (2001-04-05). "Japan goes Dutch". London Review of Books. Vol. 23 no. 7. pp. 3–7. ISSN 0260-9592. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

While Britain's was the first economy to use fossil energy to produce goods for market, the most characteristic institutions of capitalism were not invented in Britain, but in the Low Countries. The first miracle economy was that of the Dutch Republic (1588–1795), and it, too, hit a mysterious dead end. All economic success contains the seeds of stagnation, it seems; the greater the boom, the harder it is to change course when it ends. (...) Dutch market punters pioneered short selling, option trading, debt-equity swaps, merchant banking, unit trusts and other speculative instruments, much as we now know them. With them came specialised offshoots – insurance, retirement funds and other orderly forms of investment – and the maladies of capitalism: the boom-bust cycle, the world's first asset-inflation bubble, the tulip mania of 1636–37...

- ^ Wu, Wei Neng (26 Feb 2014). "Hub Cities – London: Why did London lose its preeminent port hub status, and how has it continued to retain its dominance in marine logistics, insurance, financing and law? (Civil Service College of Singapore)". Civil Service College Singapore (cscollege.gov.sg). Retrieved 26 Feb 2017.

Wu Wei Neng (2012) notes: "17th century Amsterdam was the world's first modern financial centre — the city hall, Wisselbank, Beurs (stock exchange), Korenbeurs (commodities exchange), major insurance, brokerage and trading companies were located within a few blocks of each other, along with coffee houses which served as informal trading floors and exchanges that facilitated deal-making. Financial innovations such as maritime insurance, retirement pensions, annuities, futures and options, transnational securities listings, mutual funds and modern investment banking had their genesis in 17th and 18th century Amsterdam."

- ^ Wallerstein, Immanuel: The Modern World-System II: Mercantilism and the Consolidation of the European World-Economy, 1600–1750. (Academic Press, 1980), p. 43-44. As Immanuel Wallerstein (1980) remarked, the Dutch Republic's shipbuilding industry was "of modern dimensions, inclining strongly toward standardized, repetitive methods. It was highly mechanized and used many labor-saving devices – wind-powered sawmills, powered feeders for saw, block and tackles, great cranes to move heavy timbers – all of which increased productivity."

- ^ Lunsford, Virginia W.: Piracy and Privateering in the Golden Age Netherlands. (Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), p. 69. As Richard Unger affirms, "By seventeenth-century standards, Dutch shipbuilding was a massive industry and larger than any shipbuilding industry which had preceded it."

- ^ Aymard, Maurice (ed.): Dutch Capitalism and World Capitalism / Capitalisme hollandais et capitalisme mondial [Studies in Modern Capitalism / Etudes sur le capitalisme moderne]. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Paris: Editions de la Maison des Sciences de l'Homme, 1982)

- ^ Kaletsky, Anatole: Capitalism 4.0: The Birth of a New Economy in the Aftermath of Crisis. (PublicAffairs, 2010), p. 109-110. Anatole Kaletsky (2010): "The bursting of the tulip bubble in 1637 did not end Dutch economic hegemony. Far from it. Tulipmania was followed by a century of Dutch leadership in almost every branch of global commerce, finance, and manufacturing."

- ^ Arrighi, Giovanni; Silver, Beverly (1999). Chaos and Governance in the Modern World System (Contradictions of Modernity), p. 39

- ^ Lachmann, Richard (2000). Capitalists in Spite of Themselves: Elite Conflict and European Transitions in Early Modern Europe, p. 158

- ^ Lee, Richard E. (2012). The Longue Duree and World-Systems Analysis, p. 65

- ^ Sobel, Andrew C. (2012). Birth of Hegemony: Crisis, Financial Revolution, and Emerging Global Networks, p. 54-88

- ^ Hall, Thomas D. (2000). A World-Systems Reader: New Perspectives on Gender, Urbanism, Cultures, Indigenous Peoples, and Ecology, p. 32

- ^ Sombart, Werner: The Quintessence of Capitalism: A Study of the History and Psychology of the Modern Business Man. Translated from the German by M. Epstein. (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1915), p. 144

- ^ Stringham, Edward Peter; Curott, Nicholas A. (2015), 'On the Origins of Stock Markets,' [Chapter 14, Part IV: Institutions and Organizations]; in The Oxford Handbook of Austrian Economics, edited by Peter J. Boettke and Christopher J. Coyne. (Oxford University Press, 2015, ISBN 978-0199811762), pp. 324–344

- ^ Brooks, John (1968). "The Fluctuation: The Little Crash in '62", in Business Adventures: Twelve Classic Tales from the World of Wall Street. (New York: Weybright & Talley, 1968)

- ^ Rothbard, Murray: Making Economic Sense, 2nd edition. (Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2006, ISBN 9781610165907), p. 426

- ^ "The Keynes Conundrum by David P. Goldman". First Things (firstthings.com). 1 October 2010. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

Reuven Brenner & David P. Goldman (2010): "Western societies developed the institutions that support entrepreneurship only through a long and fitful process of trial and error. Stock and commodity exchanges, investment banks, mutual funds, deposit banking, securitization, and other markets have their roots in the Dutch innovations of the seventeenth century but reached maturity, in many cases, only during the past quarter of a century."