Homophone

A homophone is a word that is pronounced the same (to varying extent) as another word but differs in meaning. A homophone may also differ in spelling. The two words may be spelled the same, as in rose (flower) and rose (past tense of rise), or differently, as in rain, reign, and rein. The term "homophone" may also apply to units longer or shorter than words, for example a phrase, letter, or groups of letters which are pronounced the same as another phrase, letter, or group of letters. Any unit with this property is said to be "homophonous".

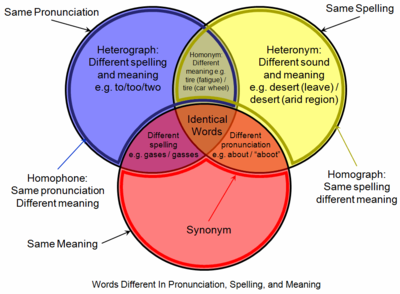

Homophones that are spelled the same are also both homographs and homonyms, e.g. the word "read," as in the sentence "He is well read," (he is very educated) vs. the sentence "I read that book," (I have finished reading that book.)[1]

Homophones that are spelled differently are also called heterographs, e.g. to, too, and two.

| Part of a series on |

| Linguistics |

|---|

|

|

Etymology[]

"Homophone" derives from the Greek homo- (ὁμο‑), "same", and phōnḗ (φωνή), "voice, utterance".

In wordplay and games[]

Homophones are often used to create puns and to deceive the reader (as in crossword puzzles) or to suggest multiple meanings. The last usage is common in poetry and creative literature. An example of this is seen in Dylan Thomas's radio play Under Milk Wood: "The shops in mourning" where mourning can be heard as mourning or morning. Another vivid example is Thomas Hood's use of "birth" and "berth" and "told" and "toll'd" (tolled) in his poem "Faithless Sally Brown":

- His death, which happen'd in his berth,

- At forty-odd befell:

- They went and told the sexton, and

- The sexton toll'd the bell.

In some accents, various sounds have merged in that they are no longer distinctive, and thus words that differ only by those sounds in an accent that maintains the distinction (a minimal pair) are homophonous in the accent with the merger. Some examples from English are:

- pin and pen in many southern American accents.

- by and buy.

- merry, marry, and Mary in most American accents.

- The pairs do, due and forward, foreword are homophonous in most American accents but not in most English accents.

- The pairs talk, torque, and court, caught are distinguished in rhotic accents such as Scottish English and most dialects of American English, but are homophones in many non-rhotic accents such as British Received Pronunciation.

Wordplay is particularly common in English because the multiplicity of linguistic influences offers considerable complication in spelling and meaning and pronunciation compared with other languages.

Malapropisms, which often create a similar comic effect, are usually near-homophones. See also Eggcorn.

Same-sounding phrases[]

Same-sounding (homophonous, or homophonic) phrases are often used in various word games. Examples of same-sounding phrases (which may only be true homophones in certain dialects of English) include:

- "ice cream" vs. "I scream" (as in the popular song "I scream. You scream. We all scream for ice cream.")

- "euthanasia" vs. "Youth in Asia"

- "depend" vs. "deep end"

- "Gemini" vs. "Jim and I" vs. "Jem in eye" vs. "gem in eye"

- "the sky" vs. "this guy" (most notably as a mondegreen in Purple Haze by Jimi Hendrix)

- "four candles" vs. "fork handles"

- "sand which is there" vs. "sandwiches there"

- "philanderers" vs. "Flanders"

- "example" vs. "egg sample"

- "some others" vs. "some mothers" vs. "smothers"

In his Appalachian comedy routine, American comedian Jeff Foxworthy frequently uses same-sounding phrases which play on exaggerated "country" accents. Notable examples include:

- Initiate: "My wife ate two sandwiches, initiate [and then she ate] a bag o' tater chips."

Mayonnaise: "Mayonnaise [Man, there is] a lot of people here tonight."

Innuendo: "Hey dude I saw a bird fly innuendo [in your window]."

Moustache: "I Moustache [must ask] you a question."

During the 1980s, an attempt was made to promote a distinctive term for same sounding multiple words or phrases, by referring to them as "oronyms". That was first proposed and advocated by Gyles Brandreth in his book The Joy of Lex (1980), and such use was also accepted in the BBC programme Never Mind the Full Stops, which featured Brandreth as a guest. Since the term oronym was already well established in linguistics as an onomastic designation for a class of toponymic features (names of mountains, hills, etc.),[2] the alternative use of the same term was not universally accepted in scholarly literature.[3]

Number of homophones[]

English[]

There are sites, for example, this archived page, which have lists of homonyms or rather homophones and even 'multinyms' which have as many as seven spellings. There are differences in such lists due to dialect pronunciations and usage of old words. In English, there are approximately 88 triples; 24 quadruples; 2 quintuples; 1 sextet, 1 septet, and 1 octet. The octet is:

- raise, rays, rase, raze, rehs, res, reais, race

Other than the two common words raise and rays, there are:

- raze – a verb meaning "to demolish, level to the ground" or "to scrape as if with a razor";

- rase – a verb meaning "to erase";

- rehs – the plural of reh, a mixture of sodium salts found as an efflorescence in India;

- res – the plural of re, a name for one step of the musical scale;

- reais – the plural of real, a currency unit of Portugal and Brazil.

If proper names are allowed, then a possible nonet would be:

- Ayr (Scottish town),

- Aire (Yorkshire River),

- Eyre (legal term and various geographic locations),

- heir,

- air,

- err (some speakers),

- ere (poetic "before"),

- e'er (poetic "ever", some speakers),

- are (unit of area; some speakers).

German[]

There are many homophones in present-day standard German. As in other languages, however, there exists regional and/or individual variation in certain groups of words or in single words, so that the number of homophones varies accordingly. Regional variation is especially common in words that exhibit the long vowels ä and e. According to the well-known dictionary Duden, these vowels should be distinguished as /ɛ:/ and /e:/, but this is not always the case, so that words like Ähre (ear of corn) and Ehre (honor) may or may not be homophones. Individual variation is shown by a pair like Gäste (guests) – Geste (gesture), the latter of which varies between /ˈɡe:stə/ and /ˈɡɛstə/ and by a pair like Stiel (handle, stalk) – Stil (style), the latter of which varies between /ʃtiːl/ and /stiːl/. Besides websites that offer extensive lists of German homophones,[4] there are others which provide numerous sentences with various types of homophones.[5] In the German language homophones occur in more than 200 cases. Of these, a few are triples like Waagen (weighing scales), Wagen (cart), wagen (to dare) and Waise (orphan) – Weise (way, manner) – weise (wise). The rest are couples like lehren (to teach) – leeren (to empty).

Japanese[]

There are many homophones in Japanese, due to the use of Sino-Japanese vocabulary, where borrowed words and morphemes from Chinese are widely used in Japanese, but many sound differences, such as the original words' tones, are lost. These are to some extent disambiguated via Japanese pitch accent (i.e. 日本 vs. 二本, both pronounced nihon, but with different pitches), or from context, but many of these words are primarily or almost exclusively used in writing, where they are easily distinguished as they are written with different kanji; others are used for puns, which are frequent in Japanese. An extreme example is kikō (hiragana: きこう), which is the pronunciation of at least 22 words (some quite rare or specialized, others common; all these examples are two-character compounds), including: 機構 (organization/mechanism), 紀行 (travelogue), 稀覯 (rare), 騎行 (horseback riding), 貴校 (school (respectful)), 奇功 (outstanding achievement), 貴公 (word for "you" used by men addressing male equals or inferiors), 起稿 (draft), 奇行 (eccentricity), 機巧 (contrivance), 寄港 (stopping at port), 帰校 (returning to school), 気功 (breathing exercise/qigong), 寄稿 (contribute an article/written piece), 機甲 (armor, e.g. of a tank), 帰航 (homeward voyage), 奇効 (remarkable effect), 季候 (season/climate), 気孔 (stoma), 起工 (setting to work), 気候 (climate), 帰港 (returning to port).

Even some native Japanese words are homophones. For example, kami (かみ) is the pronunciation of the words 紙 (paper), 髪 (hair), 神 (god/spirit), and 上 (up). These words are all disambiguated by pitch accent.

Korean[]

The Korean language contains a combination of words that strictly belong to Korean and words that are loanwords from Chinese. Due to Chinese being pronounced with varying tones and Korean's removal of those tones, and because the modern Korean writing system, Hangeul, has a more finite number of phonemes than, for example, Latin-derived alphabets such as that of English, there are many homonyms with both the same spelling and pronunciation. For example, '화장(化粧)하다': 'to put on makeup' and '화장(火葬)하다': 'to cremate'. Also, '유산(遺産)': 'inheritance' and '유산(流産)': 'miscarriage'. '방구': 'fart', and '방구(防具)': 'guard'. '밤[밤ː]': 'chestnut', and '밤': 'night'. There are heterographs, but far fewer, contrary to the tendency in English. For example, '학문(學問)': 'learning', and '항문(肛門)': 'anus'. Using hanja (한자; 漢字), which are Chinese characters, such words are written differently.

As in other languages, Korean homonyms can be used to make puns. The context in which the word is used indicates which meaning is intended by the speaker or writer.

Mandarin Chinese[]

Due to phonological constraints in Mandarin syllables (as Mandarin only allows for an initial consonant, a vowel, and a nasal or retroflex consonant in respective order), there are only a little over 400 possible unique syllables that can be produced,[6] compared to over 15,831 in the English language.[7] Chinese has an entire genre of poems taking advantage of the large amount of homophones called one-syllable articles, or poems where every single word in the poem is pronounced as the same syllable if tones are disregarded. An example is the Lion-Eating Poet in the Stone Den.

Like all Chinese languages, Mandarin uses phonemic tones to distinguish homophonic syllables, which it has five. For example, mā (妈) means "mother", má (麻) means "hemp", mă (马) means "horse", mà (骂) means "scold", and ma (吗) is a yes/no question particle. Although all these words consist of the same string of consonants and vowels, the only way to distinguish each of these words audibly is by listening to which tone the word has, and as shown above, saying a consonant-vowel string using a different tone can produce an entirely different word altogether. If tones are included, the number of unique syllables in Mandarin increases to at least 1,522.[8] However, even with tones, Mandarin retains a very large amount of homophones. Yì, for example, has at least 125 homophones,[9] and it is the pronunciation used for Chinese characters such as 义, 意, 易, 亿, 议, 一, and 已.

Many scholars believe that the Chinese language did not always have such a large number of homophones and that the phonological structure of Chinese syllables was once more complex, which allowed for a larger amount of possible syllables so that words sounded more distinct from each other.

Scholars also believe that Old Chinese had no phonemic tones, but tones emerged in Middle Chinese to replace sounds that were lost from Old Chinese. Since words in Old Chinese sounded more distinct from each other at this time, it explains why many words in Classical Chinese consisted of only one syllable. For example, the Standard Mandarin word 狮子(shīzi, meaning "lion") was simply 狮 (shī) in Classical Chinese, and the Standard Mandarin word 教育 (jiàoyù, "education") was simply 教 (jiào) in Classical Chinese.

Since many Chinese words became homophonic over the centuries, it became difficult to distinguish words when listening to documents written in Classical Chinese being read aloud. One-syllable articles like those mentioned above are evidence for this. For this reason, many one-syllable words from Classical Chinese became two-syllable words, like the words mentioned in the previous paragraph.

Even with the existence of two- or two-syllable words, however, there are even multisyllabic homophones. Such homophones even play a major role in daily life throughout China, including Spring Festival traditions, which gifts to give (and not give), political criticism, texting, and many other aspects of people's lives.[10]

Another complication that arises within the Chinese language is that in non-rap songs, tones are disregarded in favor of maintaining melody in the song.[11] While in most cases, the lack of phonemic tones in music does not cause confusion among native speakers, there are instances where puns may arise. For example, in the song Duìbùqǐ wǒ de zhōngwén bù hǎo (对不起我的中文不好) by Transition, the singer sings about his difficulty communicating with Chinese speakers as a native English speaker learning Chinese. In one line of the song, the singer says, wo yao shuijiao (我要水饺), which means "I want dumplings", but the Chinese speaker misunderstands the English speaker and thought he wanted to sleep because if tones are disregarded shuijiao (睡觉) can also mean "to sleep".[12] Although the song lacks Mandarin tones, much like most songs in Mandarin, it is implied that the English speaker probably used the wrong tones when saying the word.

Subtitles in Chinese characters are usually displayed on music videos and in songs sung on movies and TV shows to disambiguate the song's lyrics.

Vietnamese[]

It is estimated that there are approximately 4,500 to 4,800 possible syllables in Vietnamese, depending on the dialect.[13] The exact number is difficult to calculate because there are significant differences in pronunciation among the dialects. For example, the graphemes and digraphs "d", "gi", and "r" are all pronounced /z/ in the Hanoi dialect, so the words dao (knife), giao (delivery), and rao (advertise) are all pronounced /zaw˧/. In Saigon dialect, however, the graphemes and digraphs "d", "gi", and "v" are all pronounced /j/, so the words dao (knife), giao (delivery), and vao (enter) are all pronounced /jaw˧/.

Pairs of words that are homophones in one dialect may not be homophones in the other. For example, the words sắc (sharp) and xắc (dice) are both pronounced /săk˧˥/ in Hanoi dialect, but pronounced /ʂăk˧˥/ and /săk˧˥/ in Saigon dialect respectively.

Use in psychological research[]

Pseudo-homophones[]

Pseudo-homophones are pseudowords that are phonetically identical to a word. For example, groan/grone and crane/crain are pseudo-homophone pairs, whereas plane/plain is a homophone pair since both letter strings are recognised words. Both types of pairs are used in lexical decision tasks to investigate word recognition.[14]

Use as ambiguous information[]

Homophones, specifically heterographs, where one spelling is of a threatening nature and one is not (e.g. slay/sleigh, war/wore) have been used in studies of anxiety as a test of cognitive models that those with high anxiety tend to interpret ambiguous information in a threatening manner.[15]

See also[]

- Homograph

- Homonym

- Synonym

- Dajare, a type of wordplay involving similar-sounding phrases

- Perfect rhyme

- Wiktionary

References[]

- ^ According to the strict sense of homonyms as words with the same spelling and pronunciation; however, homonyms according to the loose sense common in nontechnical contexts are words with the same spelling or pronunciation, in which case all homophones are also homonyms. Random House Unabridged Dictionary entry for "homonym" at Dictionary.com

- ^ Room 1996, p. 75.

- ^ Stewart 2015, p. 91, 237.

- ^ See, e.g.

- ^ See Fausto Cercignani, Beispielsätze mit deutschen Homophonen (Example sentences with German homophones).

- ^ "Is There Any Similarities Between Chinese And English?". Learn Mandarin Chinese Online | Study Online Mandarin Chinese Courses. 2017-07-07. Retrieved 2020-12-18.

- ^ . 2016-08-22 https://web.archive.org/web/20160822211027/http://semarch.linguistics.fas.nyu.edu/barker/Syllables/index.txt. Archived from the original on 2016-08-22. Retrieved 2020-12-17. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ "Compare that with 413 syllables for Chinese if you ignore tones, 1522 syllables ... | Hacker News". news.ycombinator.com. Retrieved 2020-12-18.

- ^ Chang, Chao-Huang. "Corpus-based Adaptation Mechanisms for Chinese Homophone Disambiguation" (PDF).

- ^ "Chinese Homophones and Chinese Customs". www.yoyochinese.com. Retrieved 2020-12-18.

- ^ Services, Diplomatic Language (2016-09-08). "How do people sing in a tonal language?". Diplomatic Language Services. Retrieved 2020-12-30.

- ^ "Transition (transition) - Dui bu qi wo de zhong wen bu hao (Sorry my Chinese isn't so good ) (对不起我的中文不好!(Sorry my Chinese isn't so good!)) Pinyin Lyrics". pinyin.azlyricdb.com. Retrieved 2020-12-30.

- ^ "vietnamese tone marks pronunciation". pronunciator.com. Retrieved 2021-02-05.

- ^ Martin, R. C. (1982). The pseudohomophone effect: The role of visual similarity in nonword decisions. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 34A, 395-409.

- ^ Mogg K, Bradley BP, Miller T, Potts H, Glenwright J, Kentish J (1994). Interpretation of homophones related to threat: Anxiety or response bias effects? Cognitive Therapy and Research, 18(5), 461-77. doi:10.1007/BF02357754

Sources[]

- Franklyn, Julian (1966). Which Witch? (1st ed.). New York: Dorset Press. ISBN 0-88029-164-8.

- Room, Adrian (1996). An Alphabetical Guide to the Language of Name Studies. Lanham and London: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810831698.

- Stewart, Garrett (2015). The Deed of Reading: Literature, Writing, Language, Philosophy. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9781501701702.

External links[]

| Look up homophone in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Homophone.com – a list of American homophones with a searchable database.

- Reed's Homophones – a book of sound-alike words published in 2012

- Homophones.ml – a collection of homophones and their definitions

- Homophone Machine – swaps homophones in any sentence

- Ambiguity

- Narrative techniques

- Semantic relations

- Types of words