Hospital in Arles

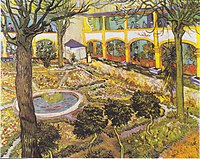

| Garden of the Hospital in Arles (F519) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Vincent van Gogh |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 73.0 cm × 92.0 cm (28.7 in × 36.2 in) |

| Location | Oskar Reinhart Collection, Winterthur, Switzerland |

Hospital at Arles is the subject of two paintings that Vincent van Gogh made of the hospital in which he stayed in December 1888 and again in January 1889. The hospital is located in Arles in southern France. One of the paintings is of the central garden between four buildings titled Garden of the Hospital in Arles (also known as the Courtyard of the Hospital at Arles); the other painting is of a ward within the hospital titled Ward of the Hospital in Arles. Van Gogh also painted Portrait of Dr. Félix Rey, a portrait of his physician while in the hospital.

Arles[]

Arles is located in a region called Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur, department of Bouches-du-Rhône in southern France. It is about 32 kilometres (20 mi) southeast of Nîmes.[1]

History[]

Arles became a successful port for trade in France during the Roman period. Many immigrants from North Africa came to Arles in the 17th and 18th centuries; their influence is reflected in many of the houses of the town that were built during that period.[2] Arles remained economically important for many years as a major port on the Rhône. The arrival of the railway in the 19th century eventually took away of much of the river trade, reducing the city's commercial business. Because Arles maintained Provençal charm it attracted artists, like Van Gogh.[3]

Van Gogh[]

Van Gogh came to Arles on February 20, 1888 and initially stayed at the lodgings at Restaurant Carrel. Signs of spring were evident in the budding almond trees and of winter by the snow-covered landscape. To Van Gogh the scene seemed like a Japanese landscape.[4]

Arles was quite a different place than anywhere else he had lived. The climate was sunny, hot and dry and the local inhabitants had more of an appearance and sound of people from Spain. The "vivid colors and strong compositional outlines" of Provence led van Gogh to call the area "the Japan of the South."[5] In this time he produced more than 200 paintings including The Starry Night [Starry Night over the Rhone], Café de Nuit and The Sunflowers.[2]

Van Gogh had few friends in Arles, although through acquaintance with Joseph Roulin, a postman, and Ginoux, the owner of Cafe de la Gare where he next roomed, he made many portraits of the Roulin family and of Madame Ginoux. Part of his difficulty in making friends was his inability to master the Provençal dialect, "whole days go by without my speaking a single word to anyone, except to order my meals or coffee." In the beginning of his time in Arles, though, he was so enthused by the setting in Provence that the lack of connection with others hadn't troubled him. In October 1888 Paul Gauguin came to Arles and joined van Gogh in his rented rooms at The Yellow House.[6] Unfortunately many of the places that van Gogh had visited and painted were destroyed during bombing raids in World War II.[2]

Events leading up to stay at Arles hospital[]

Van Gogh's mental health deteriorated and he became alarmingly eccentric, culminating in an altercation with Paul Gauguin in December 1888 following which van Gogh cut off part of his own left ear.[9] He was then hospitalized in Arles twice over a few months. His condition was diagnosed by the hospital as "acute mania with generalised delirium".[10] Dr. Félix Rey, a young intern at the hospital, also suggested there might be "a kind of epilepsy" involved that he characterised as mental epilepsy.[11] Although some, such as Johanna van Gogh, Paul Signac and posthumous speculation by doctors Doiteau & Leroy have said that van Gogh just removed part of his earlobe and maybe a little more,[12] art historian Rita Wildegans maintains that without exception, all of the witnesses from Arles said that he removed the entire left ear.[13] In January 1889, he returned to the Yellow House where he was living, but spent the following month between hospital and home suffering from hallucinations and delusions that he was being poisoned. In March 1889, the police closed his house after a petition by 30 townspeople, who called him "fou roux" (the redheaded madman). Signac visited him in hospital and van Gogh was allowed home in his company. In April 1889, he moved into rooms owned by Dr. Félix Rey, after floods damaged paintings in his own home.[14][15] Around this time, he wrote, "Sometimes moods of indescribable anguish, sometimes moments when the veil of time and fatality of circumstances seemed to be torn apart for an instant." Finally in May 1889 he left Arles for the Saint-Paul asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence,[16] having understood his own mental fragility and with a desire to leave Arles.[17]

Arles Hospital[]

The courtyard of the former Arles hospital, now named "Espace Van Gogh," is a center for van Gogh's works, several of which are masterpieces.[18] The garden, framed on all four sides by buildings of the complex, is approached through arcades on the first floor. A circulation gallery is located on the first and second floors.[19]

The Old Hospital of Arles, also known as Hôtel-Dieu-Saint-Espirit, was built in the 16th and 17th centuries. Its main entrance was on Rue Dulau in Arles. In the early 16th century there were thirty-two charitable institutions serving the city. The archbishop of Arles decided to consolidate the institutions into one organization at the center of Arles. Construction was conducted over two centuries. During excavations remains were unearthed from a protohistory period [a period between prehistory and written history ] revealing an unknown part of the ancient urban framework, as well as a necropolis from the Roman esplanade.[19]

In 1835 three wings were built to accommodate a severe cholera epidemic. In the beginning of the 20th century the hospital was modified to bring it up to medical standards of the day. In 1974 the Joseph-Imbert Hospital was opened and many functions of the Old Hospital of Arles transferred to the new hospital. By 1986 all medical departments had vacated the buildings and the hospital became part of a restoration project to create a cultural and university center. The center includes "a media library, the public records, the International College of the Literary Translation (C.I.T.L.), the university radio, a vast showroom, as well as a few shops." Architects Denis Froidevaux and Jean-Louis Tétrel, chosen for the project, preserved historic features, such as the Roman esplanade.[19]

Funding by benefactors meant the hospital serviced all patient's needs, including abandoned children and orphans. Starting in 1664 nuns of the Order of Saint Augustin cared for the patients.[19]

Paintings[]

The Ward of Arles Hospital portrays the institution and the Garden of the Hospital in Arles the scene outside his hospital room window[20] or off of a balcony.[21] Van Gogh was also occasionally able to leave the hospital complex and paint the fields.[20]

Garden of the Hospital in Arles[]

Van Gogh made a drawing of the courtyard of the hospital in June 1889.[22] The vantage point for the painting was his room within the hospital.[23] Van Gogh's description and his painting of the garden allow for identification of its flowers, such as: blue bearded irises, forget-me-nots, oleander, pansies, primroses, and poppies. The original design of the courtyard as described by Van Gogh has been preserved. Radiating segments are surrounded by a "plante bande" now filled with irises. A difference between the painting and the garden is that van Gogh increased the size of the central fish garden for better composition.[24] Adept at using color to convey mood, the shades of blue and gold in the painting seem to suggest melancholy. The yellow, orange, red and green in the painting are not vivid shades seen in other work from Arles, such as Bedroom in Arles.[25]

1889

The Oskar Reinhart Collection "Am Römerholz", Winterthur, Switzerland (F519)

1889

The Oskar Reinhart Collection "Am Römerholz", Winterthur, Switzerland (F646)

1889

Pushkin Museum, Moscow, Russia (F500)

Ward in the Hospital in Arles[]

In October 1889 van Gogh resumed painting of a fever ward titled Ward in the Hospital in Arles. The large study had been unattended for a while and van Gogh's interest was sparked when he read an article regarding Fyodor Dostoyevsky's book Souvenirs de la maison des morts ("Memories of the House of the Dead").[26]

Vincent described the painting to his sister Wil, "In the foreground a big black stove around which some grey and black forms of patients and then behind the very long ward paved in red with the two rows of white beds, the partitions white, but a lilac- or green-white, and the windows with pink curtains, with green curtains, and in the background two figures of nuns in black and white. The ceiling is violet with large beams."[26]

Debra Mancoff, author of Van Gogh's Flowers,[27] comments, "In his painting, Ward of Arles Hospital, the exaggerated length of the corridor and the nervous contours that delineate the figures of the patients express the emotional weight of his isolation and confinement."[20]

Portrait of Dr. Félix Rey[]

Van Gogh made a portrait of the physician who had treated his ear, Dr. Félix Rey, whom he had described in letters to his brother, Theo, as “brave, hardworking, and always helping people.” By January 17, 1889 Van Gogh had given the portrait to Rey as a keepsake.[28] Rey's mother reportedly deemed the portrait “hideous” and used to close a hole in the family's chicken coop. In 1901, an art dealer, possibly Lucien Molinard– who had received six Van Goghs to sell from Rey in 1900 [29] –acquired three paintings from Dr. Rey, including the portrait which was in the possession of Ambroise Vollard by 1903.[30] In 2016, the portrait was installed at the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, with an estimated value of over $50 million.[31]

Drawings[]

Theo wrote of a drawing he received, "The hospital at Arles is outstanding, the butterfly and branches of eglantine are very beautiful too: simple in colour and very beautifully drawn."[32]

Garden of Hospital in Arles

April 1889

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F1467)

Oskar Reinhart collection[]

Both the hospital garden and ward paintings were held by Oskar Reinhart[33] from a powerful family in the banking and insurance industries. At his bequest his entire collection of 500 or more works went to the nation of Switzerland upon his death in 1965. The Oskar Reinhart Am Römerholz collection is located in Winterthur.[34]

References[]

For books, also see the Bibliography using the author's last name.

- ^ "Where is Arles?". Arles Guide. Arles-guide.com. 2011. Retrieved 2011-04-29.

- ^ a b c "Arles History". Arles Guide. Arles-guide.com. 2011. Retrieved 2011-04-29.

- ^ "Arles". Provence Hideaways. Travel Writers Coop. 2011. Retrieved 2011-04-29.

- ^ Van Gogh; Leeuw, 353

- ^ "Effects of the Sun in Provence" (PDF). National Gallery of Art Picturing France (1830-1900). Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art: 121 (starting 1 of pdf). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-12.

- ^ Van Gogh; Leeuw, 385

- ^ Brooks, D. "Portrait of Doctor Félix Rey". The Vincent van Gogh Gallery, endorsed by Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. David Brooks (self-published). Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Brooks, D. "Dr. Félix Rey, interviewed by Max Braumann (1928)". The Vincent van Gogh Gallery, endorsed by Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. David Brooks (self-published). Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Maurer, 192

- ^ "Concordance, lists, bibliography: Documentation". Vincent van Gogh: The Letters. Van Gogh Museum. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ^ Naifeh and Smith (2011), 701 ff., 729, 749

- ^ Erickson, 106

- ^ Wildegans, Dr. R. "Van Gogh's Ear". Dr. Rita Wildegans. Archived from the original on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2011-04-27"It can be said that with the exception of the sister-in-law Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, who had family-related reasons for playing down the injury, not a single witness speaks of a severed earlobe. On the contrary, the mutually independent statements by the principal witness Paul Gauguin, the prostitute who was given the ear, the gendarme who was on duty in the red-light district, the investigating police officer and the local newspaper report, accord with the evidence that the artist's unfortunate "self-mutilation" involves the entire (left) ear. The existing handwritten and clearly worded medical reports by three different physicians, all of whom observed and treated Vincent van Gogh over an extended period of time in Arles as well as in the Saint-Paul asylum in Saint-Rémy ought to provide ultimate proof of the fact that the artist was missing an entire ear and not just an earlobe."

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Pickvance (1986). Chronology, 239–242

- ^ Tralbaut (1981), 265–273

- ^ Hughes, 145

- ^ Maurer, 86

- ^ Fisher, 563

- ^ a b c d "Espace Van Gogh". Visiter, Places of Interest. Arles Office de Tourisme. Archived from the original on 2012-03-23. Retrieved 2011-04-29.

- ^ a b c Mancoff, D (2006–2011). "Ward of Arles Hospital by Vincent van Gogh". HowStuffWorks. Publications International, Ltd. Retrieved 2011-04-30.

- ^ Fell, 28

- ^ Harrison, R, ed. (2011). "Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, Saint-Rémy, 17 or 18 June 1889". Van Gogh Letters. WebExhibits. Retrieved 2011-04-30.

- ^ Harris, B (2008). "A visit to Van Gogh's Arles". bob.harris.com. Retrieved 2011-04-30" See photo that shows the vantage point that matches exactly to the painting."

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Fell, 30

- ^ Acton, 109-110

- ^ a b Harrison, R, ed. (2011). "Vincent van Gogh. Letter to Wilhelmina van Gogh. Written c. 20–22 October 1889 in Saint-Rémy". Van Gogh Letters. WebExhibits. Retrieved 2011-04-29.

- ^ Mancoff

- ^ Van Gogh; Suh, 242

- ^ Feilchenfeldt, Walter (2013). Vincent Van Gogh: The Years in France: Complete Paintings 1886-1890. Philip Wilson. p. 306. ISBN 978-1781300190. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ^ Khoshbin, Shahram; Katz, Joel T. (2015). "Van Gogh's Physician". Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2 (3): ofv088. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofv088. PMC 4539511. PMID 26288801.

- ^ "Portrait of Doctor Félix Rey Oil Painting Reproduction, 1889". van gogh studio (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 23 October 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ Van Gogh; Leeuw, 447

- ^ "Collection of Oskar Reinhart Collection 'Am Römerholz'". Van Gogh Paintings. Van Gogh Gallery. 2011. Retrieved 2011-04-30.

- ^ Simonis; Johnstone; Williams, 209

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Arles. |

- Oskar Reinhart Collection am Roemerholz, Winterthur

- Old Hospital of Arles, Arles tourist office website

- Van Gogh Tour, Arles Office of Tourism

Bibliography[]

- Acton, M (197). Looking Back at Paintings. Oxon and New York. ISBN 0-415-14889-8.

- Erickson, K (1998). At Eternity's Gate: The Spiritual Vision Of Vincent van Gogh. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdsman Publishing. ISBN 0-8028-3856-1.

- Fell, D (1997) [1994]. The Impressionist Garden. London: Frances Lincoln Limited. ISBN 0-7112-1148-5.

- Fisher, R, ed (2011). Fodor's France 2011. Toronto and New York: Fodor's Travel, division of Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-0473-7.

- Hughes, Robert. Nothing If Not Critical. London: The Harvill Press, 1990 ISBN 0-14-016524-X

- Hulsker, Jan. The Complete Van Gogh. Oxford: Phaidon, 1980. ISBN 0-7148-2028-8

- Mancoff, D (1999). Van Gogh's Flowers. London: Frances Lincoln Limited. ISBN 978-0-7112-2908-2.

- Maurer, N (1999) [1998]. The Pursuit of Spiritual Wisdom: The Thought and Art of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin. Cranbury: Associated University Presses. ISBN 0-8386-3749-3.

- Naifeh, Steven; Smith, Gregory White. Van Gogh: The Life. Profile Books, 2011. ISBN 978-1-84668-010-6

- Pickvance, Ronald. Van Gogh In Saint-Rémy and Auvers (exh. cat. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), Abrams, New York 1986. ISBN 0-87099-477-8

- Simonis, D; Johnstone, S; Williams, N (2006). Switzerland. Lonely Planet Publications.

- Tralbaut, Marc Edo. Vincent van Gogh, le mal aimé. Edita, Lausanne (French) & Macmillan, London 1969 (English); reissued by Macmillan, 1974 and by Alpine Fine Art Collections, 1981. ISBN 0-933516-31-2.

- Van Gogh, V and Leeuw, R (1997) [1996]. van Crimpen, H, Berends-Albert, M. ed. The Letters of Vincent van Gogh. London and other locations: Penguin Books.

- Van Gogh, V; Suh, H (2006). Vincent van Gogh: A Self-portrait in Art and Letters. New York: Black Dog and Leventhal Publishers. ISBN 1-57912-586-7.

- 1889 paintings

- Series of paintings by Vincent van Gogh

- Paintings of Arles by Vincent van Gogh

- 1880s paintings

- Paintings in Winterthur

- Fish in art

- Water in art