House of Slaves

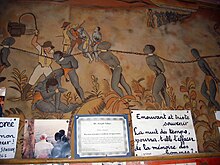

Statues and plaque at the Maison des Esclaves Memorial (2006). | |

| |

| Established | 1962 |

|---|---|

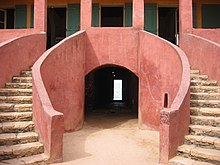

The House of Slaves (Maison des Esclaves) and its Door of No Return is a museum and memorial to the Atlantic slave trade on Gorée Island, 3 km off the coast of the city of Dakar, Senegal. Its museum, which was opened in 1962 and curated until Boubacar Joseph Ndiaye's death in 2009, is said to memorialise the final exit point of the slaves from Africa. While historians differ on how many African slaves were actually held in this building, as well as the relative importance of Gorée Island as a point on the Atlantic slave trade,[1] visitors from Africa, Europe, and the Americas continue to make it an important place to remember the human toll of African slavery.[2]

Living conditions[]

Following its construction in 1776, the House of Slaves became a holding center for enslaved African people to be exported. The House was owned by an Afro-French woman (Anna Colas Pépin), who owned several ships and participated in the slave trade.[3] Conditions in the building were harrowing, with many of the imprisoned perishing before they reached the ships. Captured enslaved people "were imprisoned in dark, airless cells", and "spent days shackled to the floor, their backs against the walls, unable to move."[3] Families were separated both at the House, with men, women, and children being held in separate quarters, as well as after boarding the ships, since most of them were not sent to the same locations.[3] Young girls, in particular, were held separately from the rest of the imprisoned, being "paraded in the courtyard so that the traders and enslavers could choose them for sex"; if they became pregnant, they were allowed to remain on the island until they gave birth.[3] Converted into a museum and memorial in 1962, the House of Slaves now stands as a testament to the human suffering and devastation caused by the slave trade.

Memorial[]

The House of Slaves was reconstructed and opened as a museum in 1962 largely through the work of Boubacar Joseph Ndiaye (1922 – 2009).[4] Ndiaye was an advocate of both the memorial and proclamation that enslaved people were held in the building in great numbers and from here transported directly to the Americas.[2] Eventually becoming curator of the Museum, Ndiaye claimed that more than a million enslaved people passed through the doors of the house. This belief has made the house both a tourist attraction and the site for state visits by world leaders to Senegal.[2]

Academic controversy[]

Since the 1980s, academics have downplayed the role that Gorée played in the Atlantic slave trade, arguing that it is unlikely that many enslaved people actually walked through the door, and that Gorée itself was marginal to the Atlantic slave trade.[2] Ndiaye and other Senegalese have always maintained that the site is more than a memorial and is an actual historic site in the transport of Africans to European colonies in the Americas, and is underappreciated by Anglophone researchers.[5][6]

Constructed around 1776,[2] the building was the home in the early 19th century to one of a class wealthy, colonial, Senegalese woman trader (the Signares), Anne Pépin or Anna Colas Pépin. Researchers argue that while the houseowner may have sold small numbers of enslaved people (kept in the now reconstructed basement cells)[2] and kept a few domestic enslaved people, the actual point of departure was 300m away at a fort on the beach. The house has been restored since the 1970s. Despite the significance of Gorée Island, some historians have made claim that only 26,000 enslaved Africans were recorded having passed through the island, of the unknown number of slaves that were exported from Africa.[2] Ndiaye and supporters have submitted that there is evidence, the building itself, was originally built to hold a large numbers of enslaved people, and that as many as 15 million people passed through this particular Door of No Return.[6]

Academic accounts, such as the 1969 statistical work of historian Philip D. Curtin, argue that enforced transports from Gorée began around 1670 and continued until about 1810, at no time more than 200 to 300 a year in important years and none at all in others. Curtin's 1969 accounting of enforced trade statistics records that between 1711 and 1810 180,000 enslaved Africans were transported from the French posts in Senegambia, most being transported from Saint-Louis, Senegal, and James Fort in modern Gambia.[7] Curtin has been quoted as stating that the actual doorway memorialised likely had no historical significance, due to the fact that it was built in the late 1770s and "late in the era [of slave trading] to be of much importance", with Britain and the United States both abolishing the slave trade in 1807.[8][9] Other academics have also pointed out that Curtin did not account for the number of individuals who died during transport or shortly after their capture, which could have added significantly to his estimate.[9] In response to these figures, popularly rejected by much of the Senegalese public, an African historical conference in 1998 claimed that records from the French trading houses of Nantes documented 103,000 slaves being from Gorée on Nantes-owned ships in a single year in the 18th century.[10] Ana Lucia Araujo has stated "it’s not a real place from where real people left in the numbers they say".[11]

Even those who argue Gorée was never important in the slave trade view the island as an important memorial to a trade that was carried on in greater scale from ports in modern Ghana and Benin.[2]

Tourism[]

Despite the controversy, the Maison des Esclaves is a central part of the Gorée Island UNESCO World Heritage site, named in 1978, and a major draw for foreign tourists to Senegal. Only 20 minutes by ferry from the city centre of Dakar, 200,000 visitors a year pass through the Museum here.[12] Many, especially those descended from enslaved Africans, describe highly emotional reactions to the place, and the pervasive influence of Ndiaye's interpretation of the historical significance of the building: especially the Door of No Return through which Ndiaye argued millions of enslaved Africans left the continent for the last time. Before his death in 2008, Ndiaye would personally lead tours through basement cells, out through the Door of No Return, and hold up to tourists iron shackles, like those used to bind enslaved Africans.[13][14] Since the publication of Alex Haley's novel Roots: The Saga of an American Family in 1976, African American tourists from the United States have made the Museum a focal point, often a highly emotion laden one, of pilgrimages hoping to reconnect with their traditional African heritage.[15]

Famous world leaders who have toured the Maison des Esclaves during their state visits to Senegal includes Pope John Paul II, Nelson Mandela, and Barack Obama.[12] Mandela was reported to have stepped away from a tour where he sat alone in a basement cell for five minutes silently reflecting on his visit in 1997.[10] Obama toured The Door of No Return on his visit in 2013.[16]

See also[]

- Diaspora tourism

- Door of Return

- Genealogy tourism (Africa)

- Year of Return, Ghana 2019

References[]

- ^ "Tiny island weathers storm of controversy" Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine. CNN Interactive, Andy Walton. 2005. Note: the link is to a reprint on the Historian's discussion list that was a prime source for the article's quotes.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h "Through the Door of No Return", TIMEeurope, June 27, 2004.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Porter, Anna (2014). "Goree Island: The Door of No Return". Queen's Quarterly. 1: 43.

- ^ "B. J. Ndiaye, Curator of Landmark in Slave Trade, Dies at 86". Agence France-Presse. The New York Times. 18 February 2009. Retrieved 19 February 2009.

- ^ Laurie Goering, "Role of Gorée Island in slave trade now disputed by historians". Chicago Tribune, February 1, 2005.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sue Segar, "Senegal's island of pain" Archived 2005-11-19 at the Wayback Machine. News24(SA)/Panapress. August 18, 2004.

- ^ UNESCO (2001).

- ^ Adam Goodheart, "The World; Slavery's Past, Paved Over Or Forgotten". New York Times, July 13, 2003.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Porter, Anna. "Goree Island: The Door of No Return". Queen's Quarterly. 1: 44.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Howard W. French, "Goree Island Journal; The Evil That Was Done Senegal: A Guided Tour". The New York Times, Friday, March 6, 1998.

- ^ Fisher, Max (28 June 2013). "What Obama really saw at the 'Door of No Return,' a disputed memorial to the slave trade". Retrieved 1 October 2017 – via www.washingtonpost.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b John Murphy, "Powerful symbol, weak in facts". Slavery: A thriving tourist trade has been built around the dubious historic role of a Senegal island. Baltimore Sun, June 30, 2004.

- ^ See the images of Ndaiye in NYT (2008) and UNESCO (2002).

- ^ Rohan Preston, In the haunting confines of a slave portal, a pilgrim confronts his ancestors' past Archived 2009-02-20 at the Wayback Machine. Minneapolis Star Tribune, January 10, 2007.

- ^ See Ebron (1999), Nicholls (2004), and Austen (2001).

- ^ Nakamura, David (June 27, 2013). "Obamas visit Door of No Return, where slaves once left Africa". Washington Post. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

Further reading[]

- Ralph A. Austen. "The Slave Trade as History and Memory: Confrontations of Slaving Voyage Documents and Communal Traditions". The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, Vol. 58, No. 1, New Perspectives on the Transatlantic Slave Trade (January 2001), pp. 229–244

- Steven Barboza. Door of No Return: The Legend of Gorée Island. Cobblehill Books (1994).

- Maria Chiarra. "Gorée Island, Senegal". In Trudy Ring, Robert M. Salkin, Sharon La Boda (eds), International Dictionary of Historic Places. Taylor & Francis (1996), pp. 303–306. ISBN 1-884964-03-6

- Paulla A. Ebron. "Tourists as Pilgrims: Commercial Fashioning of Transatlantic Politics". American Ethnologist, Vol. 26, No. 4 (November 1999), pp. 910–932

- Saidiya Hartman. "The Time of Slavery". South Atlantic Quarterly, 2002 101(4), pp. 757–777.

- Boubacar Joseph Ndiaye. Histoire et traite de noirs à Gorée. UNESCO, Dakar (1990).

- David G. Nicholls. "African Americana in Dakar's Liminal Spaces", in Joanne M. Braxton, Maria Diedrich (eds), Monuments of the Black Atlantic: slavery and memory. LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster (2004), pp. 141–151. ISBN 3-8258-7230-0

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maison des Esclaves. |

- Gorée : The Slave Island. BBC News. 8 July 2003.

- la Maison des Esclaves. Visite Virtuel d'Ile de Goree: UNESCO World Heritage Africa.

- Report on the Slave Trade Archives project, under the Memory of the World Programme, in Dakar, Senegal, 7-11 January 2002 Ahmed A. Bachr, UNESCO.

- UNESCO World Heritage site 26 (1978) listing: Goree Island.

- L'esclavage: Campagne internationale pour la sauvegarde du patrimoine architectural de l'île de Gorée. UNESCO (2001).

Coordinates: 14°40′04″N 17°23′50″W / 14.66778°N 17.39722°W

- African slave trade

- Buildings and structures in Dakar

- History of Senegal

- Museums in Senegal

- Museums established in 1962

- 1962 establishments in Senegal

- Slavery museums

- Slavery memorials

- Slave cabins and quarters

- Gorée