Howard K. Smith

Howard K. Smith | |

|---|---|

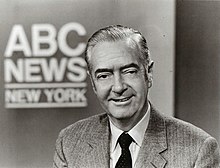

Smith in 1972 | |

| Born | Howard Kingsbury Smith May 12, 1914 Ferriday, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Died | February 15, 2002 (aged 87) Bethesda, Maryland, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | News anchor |

| Years active | 1940–2000 |

| Political party | Democratic Party |

| Spouse(s) | Benedicte Traberg Smith (1942–2002, his death) |

| Children | 2 |

Howard Kingsbury Smith (May 12, 1914 – February 15, 2002) was an American journalist, radio reporter, television anchorman, political commentator, and film actor. He was one of the original members of the team of war correspondents known as the Murrow Boys.

Early life and education[]

Smith was born in Ferriday in Concordia Parish in eastern Louisiana near Natchez, Mississippi, to Howard K. Smith, a nightwatchman descended from a poor "gentleman-farming" family of Lettsworth, Pointe Coupee Parish (north of Baton Rouge), and the former Minnie Gates, the daughter of a Cajun riverboat pilot.[1]

Smith worked his way through Tulane University in New Orleans, studying German and journalism. After his graduation in 1936, with both Bachelor of Arts degrees,[2] he signed on as a deckhand with a ship bound for Germany, where he briefly studied at Heidelberg University. In 1936, he spent a year as a reporter in New Orleans before securing a Rhodes Scholarship to Merton College, Oxford, from which he graduated in 1939.[3] Smith became active in student politics, mostly protesting Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain's seemingly soft attitude toward Nazism. While at Oxford, he was the first American to chair the Oxford University Labour Club.[4]

Early career and CBS years[]

World War II[]

Upon graduating, Smith worked for the New Orleans Item, with United Press in London, and with The New York Times. In January 1940, Smith was sent to Berlin, where he joined the Columbia Broadcasting System under Edward R. Murrow.[3] He visited Hitler's mountain retreat at Berchtesgaden and interviewed many leading Nazis, including Hitler himself, Schutzstaffel or "SS" leader Heinrich Himmler and Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels. When Smith refused to include Nazi propaganda in his reports, the Gestapo seized his notebooks and expelled him from the country. He left for Switzerland on December 6, 1941, the day before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.[4]

He was one of the last American reporters to leave Berlin before Germany and the United States went to war. His 1942 book, Last Train from Berlin: An Eye-Witness Account of Germany at War describes his observations from Berlin in the year after the departure of Berlin Diary author William L. Shirer. Last Train from Berlin became an American best-seller and was reprinted in 2001, shortly before Smith's death.

Unable to leave Switzerland, where he and his young wife spent most of the war, Smith reported whatever the Swiss government would permit. After the liberation of France, he began reporting on Germany and central Europe from Berne. By the winter of 1944–1945, he began sending vivid radio accounts of the German counter-attack in the Ardennes known as the Battle of the Bulge, and he accompanied Allied forces across the Rhine River and into Berlin.[4]

Smith became a significant member of the "Murrow Boys" that made CBS the dominant broadcast news organization of the era. In May 1945, he returned to Berlin to recap the German surrender.

Post-war[]

In 1946, Smith went to London for CBS with the title of chief European correspondent.[3] In 1947, he made a long broadcasting tour of most of the nations of Europe, including behind the Iron Curtain. In 1949, Knopf published his The State of Europe, a 408-page country-by-country survey of Europe that drew on these experiences and that argued "both the American and the Russian policies are mistaken"; he advocated more "social reform" for Western Europe and more "political liberty" for Eastern Europe.

Despite these criticisms of Soviet policies, Smith was one of 151 alleged Communist sympathizers named in the Red Channels report issued in June 1950 at the beginning of the Red Scare, effectively placing him on the Hollywood blacklist.

In 1959, Smith hosted a 21-week public affairs series entitled Behind the News with Howard K. Smith. Topics included Nikita Khrushchev (a two-parter), the St. Lawrence Seaway, Fidel Castro, and unemployment in distressed areas.

In 1960, having established residence earlier in Bethesda, Maryland, Smith chaired the first-ever televised presidential debates, held between U.S. Senator John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts and Vice President Richard M. Nixon.

In late 1961, Smith left his job at CBS when a dispute erupted over the documentary Who Speaks for Birmingham?. This in-depth investigation concerned the battle between civil rights forces and the police of Birmingham, Alabama. Smith, an advocate of desegregation, concluded his commentary at the end of the program by recalling the admonition commonly attributed to Edmund Burke—"All that is necessary for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing." Smith was told to remove the Burke quote from the end of the broadcast. Network president and founder William S. Paley declined to support Smith over the matter, and Smith promptly left the network after twenty years of service. Smith declared that his hatred of discrimination stemmed from living in the racially segregated American South and from watching the Nazis in Europe during the world war.[4]

ABC, 1962 – 1979[]

Smith moved to ABC at a time its news division was a distant third among the Big Three networks. After the 1962 mid-term elections, Smith presented a documentary entitled, "The Political Obituary of Richard Nixon" as part of his series (1962–1963). Smith referred to Nixon's "last press conference" after his disastrous losing campaign against Democrat Edmund G. "Pat" Brown, Sr., for governor of California. In that exchange, the former vice president famously told reporters that they would not "have Nixon to kick around any more." Smith included in the broadcast an interview with Nixon's longstanding nemesis Alger Hiss, a convicted Cold War perjurer.[4] Howard K. Smith: News and Comment aired in the 10:30 Eastern slot on Sundays, opposite CBS's long-running quiz program What's My Line? hosted by John Charles Daly, who had been the first-ever ABC news anchor. ABC stood by Smith on the Nixon "obituary", but sponsors dried up for the program thereafter. It was revived in the 1963–1964 season as simply ABC News Reports.[4][5]

Smith was a frequent interviewer with Bob Clark on the ABC Sunday news program, Issues and Answers, which began in 1960 and was subsequently revamped and renamed in 1981 as This Week with David Brinkley.

On June 5, 1968, Smith and fellow newsman Bill Lawrence were anchoring coverage of the California presidential primary that had stretched to 3 am. New York time. As the closing credits for the special were airing, word came in that United States Senator Robert F. Kennedy of New York had been shot at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. ABC simply showed a wide shot of the chaotic newsroom for several minutes until Smith was able to confirm the initial story and go back on the air with a special report. He and Lawrence continued at their anchor desks for several more hours for reports of Kennedy's condition.

In the summer of 1968, Smith moderated a series of debates on ABC between conservative journalist William F. Buckley Jr. and liberal author Gore Vidal.[6]

In 1969, the veteran reporter became the co-anchor of the ABC Evening News, first with Frank Reynolds, then the following year with another CBS alumnus, Harry Reasoner. He began making increasingly conservative commentaries, in particular a hard-line stance in support of the Vietnam War. He contrasted United States President Lyndon B. Johnson's decisive stance in Vietnam with the international failure to take preemptive action against Hitler.[4] During this period, his son, future ABC newsman, (April 25, 1945 – April 7, 2004), was serving with the U.S. Army 7th Cavalry Regiment in South Vietnam[citation needed] and fought at the Battle of Ia Drang.[7] These commentaries endeared him to President Nixon, who rewarded him with a rare, hour-long, one-on-one interview in 1971, at the height of the administration's animus against major newspapers, CBS, and NBC, despite Smith's having broadcast his "political obituary" only nine years earlier.

During the 1972 presidential campaign, a letter was published that Smith had written to Democratic United States Senator Edmund S. Muskie of Maine, indicating Smith's full support for Muskie. The endorsement was written on stationery with ABC's letterhead. Nothing ever came of this controversy, however, and Smith kept his job. Notwithstanding his past temporary friendly relations with Nixon (who defeated U.S. United States Senator George S. McGovern of South Dakota for re-election), Smith became the first national television commentator to call for Nixon's resignation over Watergate.[citation needed]

Smith remained as co-anchor at ABC until 1975, after which Reasoner anchored solo until Barbara Walters joined the broadcast a year later. Smith continued as an analyst until 1979; he left the network nearing full retirement, and as the Roone Arledge era was beginning at ABC News. Sources say that Smith was embittered over the reduction in time allowed for his commentaries and hence resigned after he criticized the revamped World News Tonight format as a "Punch and Judy show."[8]

Awards and film roles[]

Among honors which Smith received over the years were DuPont Awards in 1955[3] and 1963, a Sigma Delta Chi Award for radio journalism in 1957, and an award from the American Jewish Congress in 1960. In 1962 he received the Paul White Award from the Radio Television Digital News Association.[9]

Smith also appeared in a number of films, often as himself; The Best Man (1964), The Candidate (1972),[citation needed] The President's Plane Is Missing (1973, a made-for-television production of the Robert J. Serling novel of the same name), Nashville (1975), Network (1976), The Pink Panther Strikes Again (1976), Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), The Pursuit of D. B. Cooper (1981), The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas (1982), "The Odd Candidate" (1974) episode of the television series The Odd Couple (playing himself), the "Kill Oscar" episode (1977) of The Bionic Woman (playing himself anchoring an ABC newscast), and both V (1983) and the subsequent 1984 television series. He appeared as the Narrator in the 1987 film Escape From Sobibor.

Along with Last Train from Berlin, he wrote three other books, The Population Explosion (1960), the children's book Washington, D.C.: The Story of our Nation's Capital (1967), and a memoir Events Leading Up to My Death: The Life of a Twentieth-Century Reporter (1996).

Family life[]

Smith's son, Jack, as an ABC correspondent received Peabody and Emmy awards for his coverage of technology; he was 58 when he died in 2004 of pancreatic cancer in Marin County, Calif.[10]

Smith also had a daughter, Catherine H. Smith of Los Angeles, by his March 1942 marriage to the former Benedicte "Bennie" Traberg (September 25, 1921 – October 29, 2008), a journalist originally from Denmark whom Smith called the most impressive person he had ever known, "far above presidents and generals." There were three grandchildren.[1]

Catherine Smith, who wrote her mother's obituary, quoted from Smith's 1996 memoirs Events Leading Up to My Death, that their relationship "was born in an atmosphere of acute crisis." With World War II heating up, recalled Catherine Smith, and both of them heading out of the German capital, they decided to marry just four days after their first date. Her young age required her return to Nazi-occupied Denmark for parental approval and the Danish queen's intervention to obtain travelling papers, but the couple reunited successfully three months later in Berne, Switzerland."[10]

Mrs. Bennie Smith managed her husband's career, handled the finances and investments, and helped with the processing of his publications. Catherine Smith noted that her mother was the one most responsible for the development of his patrician demeanor. "She was a formidable presence at his side and major force behind his success. She edited all his books and articles, and was his agent, negotiating all his broadcasting and other contracts. She arranged every aspect of what, in later years, became a very lucrative speaking career. When my parents traveled on the lecture circuit, she once laughingly told a Lansing, Mich. paper...: 'My husband never knows where his trips will take him .... It's not until we get ready to board the plane that he'll inquire 'Where are we going?' and then I will tell him.'"[10]

The Smiths lived at their Potomac River home in Bethesda, Maryland, from 1958 until his 2002 death from pneumonia, after which Mrs. Smith relocated to a condominium on Marco Island, Fla. She died in 2008 at age 87 of complications from hydrocephalus. The Smiths are interred at historic Oak Hill Cemetery in the Georgetown section of Washington, D.C.[10]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Howard K. Smith", Delta Music Museum Celebrities, Ferriday, Louisiana, p. 2.

- ^ Who's Who in America, 1972 ed.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Levens, R.G.C., ed. (1964). Merton College Register 1900–1964. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. p. 287.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "Harold Jackson, Obituaries, "Howard K Smith: Legendary US broadcaster famed for his independent reporting". The Guardian. London. February 20, 2002. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ^ McNeil, Alex (1996). Total Television (4th ed.). New York: Penguin Books. p. 395.

- ^ Brody, Richard (August 17, 2015). "Buckey, Vidal, and the Birth of Buzz". The New Yorker. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ^ http://www.vietnamwall.org/news.php?id=1

- ^ "Howard K. Smith". museum.tv. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- ^ "Paul White Award". Radio Television Digital News Association. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d ""Benedicte Traberg Smith, widow of broadcast journalist Howard K. Smith, dies at 87", October 30, 2008". marconews.com. Retrieved December 26, 2008.[dead link]

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Howard K. Smith. |

- Museum of Broadcast Communications

- Who's Who in America, 1972 edition

- Howard K. Smith at The Interviews: An Oral History of Television

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- 1914 births

- 2002 deaths

- 20th-century American journalists

- American broadcast news analysts

- American male film actors

- 20th-century American memoirists

- American non-fiction writers

- American radio reporters and correspondents

- American Rhodes Scholars

- American television news anchors

- Burials at Oak Hill Cemetery (Washington, D.C.)

- Cajun people

- Deaths from pneumonia

- People from Bethesda, Maryland

- People from Ferriday, Louisiana

- Writers from New Orleans

- Alcee Fortier High School alumni

- Tulane University alumni

- Alumni of Merton College, Oxford

- American war correspondents

- Male actors from New Orleans

- ABC News personalities

- CBS News people

- American male journalists

- Maryland Democrats

- Hollywood blacklist

- 20th-century American male actors