Hyakumantō Darani

| Hyakumantō Darani (百万塔陀羅尼) | |

|---|---|

| One Million Pagodas and Dharani Prayers | |

| |

| |

| Material | Washi (paper), ink, wood |

| Writing | Japanese |

| Created | 764-770 C.E. |

| Present location | various |

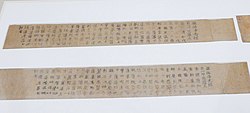

The Hyakumantō Darani (百万塔陀羅尼), or the "One Million Pagodas and Dharani Prayers", are a series of Buddhist prayers or spells that were printed on paper and then rolled up and housed in wooden cases that resemble miniature pagodas in both appearance and meaning. Although woodblock-printed books from Chinese Buddhist temples were seen in Japan as early as the 8th century, the Hyakumantō Darani are the earliest surviving examples of printing in Japan and, alongside the Korean Dharani Sutra, are considered to be some of the world's oldest extant printed matter.

Manufacture[]

The production of the Hyakumantō Darani was a huge undertaking. In the year of her resumption of the throne, 764, the Empress Shōtoku commissioned the one million small wooden pagodas (Hyakumantō (百万塔)), each containing a small piece of paper (typically 6 x 45 cm) printed with a Buddhist text, the Vimalasuddhaprabhasa mahadharani sutra (Mukujōkō daidarani kyō (無垢淨光大陀羅尼經)[1]). It is thought they were printed in Nara, where the facilities, craftsmen and skills existed to undertake such large scale production.[2] Marks on the bases of the wooden pagodas indicate that they were worked on lathes and studies of these have identified that more than 100 different lathes were used in their production.[3] More than 45,000 pagodas and 3,962 printed dharani survive in the Hōryū-ji temple near Nara, but globally fewer than 50,000 pagodas are known to still exist.[4] Their creation was completed around 770, and they were distributed to temples around the country.

Historical context[]

There are various theories around Shōtoku's motives for commissioning the Hyakumantō Darani. One is that of remorse and thanksgiving for the suppression of the Emi Rebellion of 764, and another is as an assertion of power and control over resources, but the act could equally serve both political and devotional aims.[5] Either it was felt that printing as a technology had served its ritual purpose through the creation of the Hyakumantō Darani, or simply that the cost of this mass production proved prohibitive, but printing technology did not become widespread until the tenth century and the production, and distribution of books continued to rely heavily on hand-copying manuscripts.[6]

References[]

- ^ Mukujôkô daidarani kyô = The Sutra of the Great Incantations of Undefiled Pure Light = Vimalasuddhaprabhasa Mahadharani Suttra

- ^ Kornicki, Peter (11 January 2012). "The Hyakumantō Darani and the Origins of Printing in Eighth-Century Japan". International Journal of Asian Studies. 9 (1): 43–70. doi:10.1017/S1479591411000180. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ Kornicki, Peter (11 January 2012). "The Hyakumanto Darani and the Origins of Printing in Eighth-Century Japan". International Journal of Asian Studies. 9 (1): 56. doi:10.1017/S1479591411000180. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ Kornicki, Peter (11 January 2012). "The Hyakumanto Darani and the Origins of Printing in Eighth-Century Japan". International Journal of Asian Studies. 9 (1): 45. doi:10.1017/S1479591411000180. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ Kornicki, Peter (11 January 2012). "The Hyakumanto Darani and the Origins of Printing in Eighth-Century Japan". International Journal of Asian Studies. 9 (1): 57–59. doi:10.1017/S1479591411000180. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ Kornicki, Peter (11 January 2012). "The Hyakumanto Darani and the Origins of Printing in Eighth-Century Japan". International Journal of Asian Studies. 9 (1): 57–59. doi:10.1017/S1479591411000180. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

Further reading[]

- Yiengpruksawan, Mimi Hall (1987). One Millionth of a Buddha: The "Hyakumantō Darani" in the Scheide Library. The Princeton University Library Chronicle, 48 (3), 224-238. doi:10.2307/26410044

- McBride, Richard D. II (2011). Practical Buddhist Thaumaturgy: The "Great Dhāraṇī on Immaculately Pure Light" in Medieval Sinitic Buddhism, Journal of Korean Religions 2 (1), 33-73

- Kornicki, Peter (2012). The Hyakumanto Darani and the Origins of Printing in Eighth-Century Japan, International Journal of Asian Studies, 9 (1), pp. 43–70, Cambridge University Press

External links[]

- The First Printed Text in the World, Standing Tall and Isolated in Eighth-century Japan: Hyakumanto Darani by Robert G. Sewell

- Example from the Schøyen Collection

- (in Japanese) Digital Exhibition of National Diet Library

- Hyakumantō darani (FG.870.1-4) A Pagoda and four darani in the collections of Cambridge University Library and digitised in full, complete with a 3D model of the Pagoda, in Cambridge Digital Library

- Woodcuts

- World Digital Library exhibits

- Buddhist mantras

- Buddhism in the Nara period

- Printmaking stubs

- Japanese history stubs