Icebox

An icebox (also called a cold closet) is a compact non-mechanical refrigerator which was a common early-twentieth-century kitchen appliance before the development of safely powered refrigeration devices. Before the development of electric refrigerators, iceboxes were referred to by the public as "refrigerators". Only after the invention of the modern day electric refrigerator did early non-electric refrigerators become known as iceboxes.[1] The terms ice box and refrigerator were used interchangeably in advertising as long ago as 1848.[2]

Origin[]

The first recorded use of refrigeration technology dates back to 1775 BC in the Sumerian city of Terqa.[3] It was there that the region's King, Zimri-lim, began the construction of an elaborate ice house fitted with a sophisticated drainage system and shallow pools to freeze water in the night.[3] Using ice for cooling and preservation was nothing new at this point, but these ice houses paved the way for their smaller counterpart, the icebox, to come into existence.[4] The more traditional icebox dates back to the days of ice harvesting, which had hit an industrial high that ran from the mid-19th century until the 1930s, when the refrigerator was introduced into the home. Most municipally consumed ice was harvested in winter from snow-packed areas or frozen lakes, stored in ice houses, and delivered domestically. In 1827 the commercial ice cutter was invented, which increased the ease and efficiency of harvesting natural ice. This invention made ice cheaper and in turn helped the icebox become more common.[5] Up until this point, iceboxes were used for personal means but not for mass manufacturing. By the 1840s, various companies appeared including Sears, The Baldwin Refrigerator Company, and the Ranney Refrigerator Company started getting involved in the icebox manufacturing industry.[6] D. Eddy & Son of Boston is considered to be the first company to produce iceboxes in mass quantities.[7] During this time, many Americans desired big iceboxes. Such companies like the Boston Scientific Refrigerator Company, introduced iceboxes which could hold up to 50 lbs of ice.[8] In a 1907 survey of expenditures of New York City inhabitants, 81% of the families surveyed were found to possess "refrigerators" either in the form of ice stored in a tub or iceboxes.[9] The effort of the icebox manufacturing industry and its improved technology allowed the United States' value to rise from $4.5 million in 1889 to $26 million in 1919.[10]

Design[]

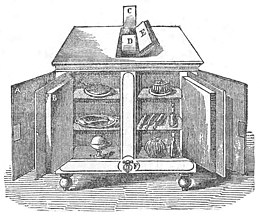

B. Typical Victorian icebox, of oak with tin or zinc shelving and door lining.

C. An oak cabinet icebox that would be found in well-to-do homes.

The icebox was invented by an American farmer and cabinetmaker named Thomas Moore in 1802.[11] Moore used the icebox to transport butter from his home to the Georgetown markets, which allowed him to sell firm, brick butter instead of soft, melted tubs like his fellow vendors at the time. His first design consisted of an oval cedar tub with a tin container fitted inside with ice between them, all wrapped in rabbit fur to insulate the device.[11] Later versions would include hollow walls that were lined with tin or zinc and packed with various insulating materials such as cork, sawdust, straw or seaweed.[12] A large block of ice is held in a tray or compartment near the top of the box. Cold air circulates down and around storage compartments in the lower section. Some finer models have spigots for draining ice water from a catch pan or holding tank. In cheaper models, a drip pan is placed under the box and has to be emptied at least daily. The user has to replenish the melted ice, normally by obtaining new ice from an iceman. The design of the icebox allowed perishable foods to be stored longer than before and without the need for lengthier preservation processes such as smoking, drying, or canning.[13] Refrigerating perishables also had the added benefit of not altering the taste of what it is preserving.[14]

Ice collection and distribution[]

Underground pits with the constant underground temperature of 12 °C (54 °F) had been used since Roman times to help preserve ice collected during winter.[16] The temperature of the soil is held relatively constant year-round when taken below the frost line, located 0.9 to 1.5 m (3 to 5 ft) below the surface, and varies from about 7 and 21 °C (45 and 70 °F) depending on the region.[17] Prior to the convenience of having refrigeration inside the home, cold storage systems would often be located underground in the form of a pit. These pits would be deep enough to provide thorough insulation and also to deter animals from intruding on the perishable items within. Early examples used straw and sawdust compacted along the sides of ice to provide further insulation and to slow the ice melting process.[16]

By the year 1781, personal ice pits were becoming more advanced. The Robert Morris Ice House, located in Philadelphia, brought new refrigeration technologies to the forefront. This pit contained a drainage system for water runoff as well as the use of brick and mortar for its insulation. The octagon-shaped pit, approximately 4 meters in diameter located 5.5 meters underground was capable of storing ice that was obtained during the winter months to the next October or November.[18] Ice blocks collected during winter months could later be distributed to customers. As the icebox began to make its way into homes during the early to mid 19th century, ice collection and distribution expanded and soon became a global industry.[19] During the latter half of the 19th century, natural ice became the second most important US export by value, after cotton.[19]

Impact and legacy[]

As the techniques for food preservation steadily improved, prices decreased and food became more readily available.[20] As more households adopted the icebox, the overall quality and freshness of this food was also improved. Iceboxes meant that people were able to go to the market less and could more safely store leftovers. All of this contributed to the improvement of the population's health by increasing the fresh food readily able to be consumed and the overall safety of that food.[21] However, with metropolitan growth, many sources of natural ice became contaminated from industrial pollution or sewer runoff. Thanks to the icebox manufacturing industry's efforts, a new innovative idea in cooling came about: air circulation. The idea for air circulation in refrigeration systems stems back to John Schooley, who wrote about his process in the 1856 Scientific American, a popular science magazine. Schooley described the process as “Combining an ice receptacle with the interior of a refrigerator… a continuous circulation of air shall be kept up through the ice in said receptacle and through the interior of the refrigerator… so that the circulation air shall deposit its moisture on the ice every time it passes through it, and be dried and cooled.” [22] This idea of air circulation and cold led to the eventual invention of the mechanical, gas-driven refrigerators. As these early mechanical refrigerators became available, they were installed at large industrial plants producing ice for home delivery.

By the early 1930s, mechanical ice machines gradually began to rise over the ice harvesting industry thanks to its ability to produce clean, sanitary ice independently and year-round. Over time, as the mechanical ice machines became smaller, cheaper, and more efficient, they easily replaced the hassle of getting ice from a source. For example, the De La Vergne Refrigerating Machine Company of New York, New York could produce up to 220 tons of ice in a single day from a single machine.[23] With widespread electrification and safer refrigerants, mechanical refrigeration in the home became possible. With the development of the chlorofluorocarbons (along with the succeeding hydrochlorofluorocarbons and hydrofluorocarbons), that came to replace the use of toxic ammonia gas, the refrigerator replaced the icebox, though icebox is still sometimes used to refer to mechanical refrigerators.

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Rees, Jonathan (2013-12-15). Refrigeration Nation. ISBN 978-1-4214-1106-4.

- ^ [1], Description of a View of the City of Paris, Taken from the Place de la, London, 1848.

- ^ a b Jackson, Tom (2015). Chilled : How refrigeration changed the world, and might do so again. New York: Bloomsbury. pp. 15–16. ISBN 9781472911438. OCLC 914183858.

- ^ Bjornlund, Lydia (2015). How the Refrigerator Changed History. Minnesota: ABDO. pp. 23–25. ISBN 9781629697710.

- ^ Landau, Elaine (2006). The History of Everyday Life. New York City, New York: Twenty-First Century Books. p. 32. ISBN 0-8225-3808-3.

- ^ Jones, Joseph (1981). American Ice Boxes. Humble, TX: Jobeco Books. pp. 46–47, 66. ISBN 978-0960757206.

- ^ Jones, Joseph (1981). American Ice Boxes. Humble, TX: Jobeco Books. pp. 46–47, 66. ISBN 978-0960757206.

- ^ Boston Scientific Refrigerator Company. 1877–78. pp. 6–7.

- ^ Chapin, Robert Coit (1909). The Standard Of Living Among Workingmen's Families in New York City. New York: Charities Publication Committee. p. 136. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ Anderson, Jr, Oscar (1953). Refrigeration in America. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 114–115.

- ^ a b "Thomas Moore". www.monticello.org. Retrieved 2019-03-08.

- ^ "The History of Household Wonders: History of the Refrigerator". History.com. A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on 26 March 2008. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- ^ "Keeping your (food) cool: From ice harvesting to electric refrigeration". National Museum of American History. 2015-04-20. Retrieved 2019-04-18.

- ^ "Ellen W. Randolph (Coolidge) to Martha Jefferson Randolph, 24 Aug. 1819 | Jefferson Quotes & Family Letters". tjrs.monticello.org. Retrieved 2019-04-18.

- ^ War Department. 1789-9/18/1947 (1918-09-16). Girls deliver ice. Heavy work that formerly belonged to men only is being done by girls. The ice girls are delivering ice on a route and their work requires brawn as well as the partriotic ambition to help. Series: American Unofficial Collection of World War I Photographs, 1860 - 1952.

- ^ a b "Filling the Ice House".

- ^ French, Roger. "Ground Source Heat Exchange".

- ^ "The First Icebox In America".

- ^ a b Gavroglu, Kostas. History of Artificial Cold, Scientific, Technological and Cultural Issues. Springer. p. 135. ISBN 978-94-007-7198-7.

- ^ Rees, Jonathan (2018). Before the refrigerator : how we used to get ice. Baltimore: JHU Press. pp. 4–7. ISBN 9781421424583. OCLC 1019837619.

- ^ Krasner-Khait, Barbara. "The Impact of Refrigeration". History Magazine. Moorshead Magazine. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- ^ Schooley, John (Nov 24, 1855). "Unknown". Scientific American. 11: 82. Cite uses generic title (help)

- ^ Sanders, Walter (1922). Ice Delivery. Chicago: Nickerson & Collins Company. pp. 86–89.

Further reading[]

- Rees, Jonathan (2013). Refrigeration Nation: A History of Ice, Appliances, and Enterprises in America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Refrigerators and food preservation in foreign countries. United States Bureau of Statistics, Department of State. 1890.

External links[]

| Look up icebox in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Media related to Iceboxes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Iceboxes at Wikimedia Commons- "What's an Ice Box?" Historical Highlights from the DeForest Area Historical Society, DeForest, Wisconsin

- Home appliances

- Food preservation

- Cooling technology

- Food storage

- Water ice