Illuminated manuscript

An illuminated manuscript is a manuscript in which the text is supplemented with such decoration as initials, borders (marginalia), and miniature illustrations. In the strictest definition, the term refers only to manuscripts decorated with either gold or silver; but in both common usage and modern scholarship, the term refers to any decorated or illustrated manuscript from Western traditions. Comparable Far Eastern and Mesoamerican works are described as painted. Islamic manuscripts may be referred to as illuminated, illustrated, or painted, though using essentially the same techniques as Western works.

The earliest extant substantive illuminated manuscripts are from the period 400 to 600, produced in the Kingdom of the Ostrogoths and the Eastern Roman Empire. Their significance lies not only in their inherent artistic and historical value, but also in the maintenance of a link of literacy offered by non-illuminated texts. Had it not been for the monastic scribes of Late Antiquity, most literature of Greece and Rome would have perished. As it was, the patterns of textual survivals were shaped by their usefulness to the severely constricted literate group of Christians. Illumination of manuscripts, as a way of aggrandizing ancient documents, aided their preservation and informative value in an era when new ruling classes were no longer literate, at least in the language used in the manuscripts.

The majority of extant manuscripts are from the Middle Ages, although many survive from the Renaissance, along with a very limited number from Late Antiquity. The majority are of a religious nature. Especially from the 13th century onward, an increasing number of secular texts were illuminated. Most illuminated manuscripts were created as codices, which had superseded scrolls. A very few illuminated fragments survive on papyrus, which does not last nearly as long as parchment. Most medieval manuscripts, illuminated or not, were written on parchment (most commonly of calf, sheep, or goat skin), but most manuscripts important enough to illuminate were written on the best quality of parchment, called vellum.

Beginning in the Late Middle Ages, manuscripts began to be produced on paper.[1] Very early printed books were sometimes produced with spaces left for rubrics and miniatures, or were given illuminated initials, or decorations in the margin, but the introduction of printing rapidly led to the decline of illumination. Illuminated manuscripts continued to be produced in the early 16th century but in much smaller numbers, mostly for the very wealthy. They are among the most common items to survive from the Middle Ages; many thousands survive. They are also the best surviving specimens of medieval painting, and the best preserved. Indeed, for many areas and time periods, they are the only surviving examples of painting.

History[]

Art historians classify illuminated manuscripts into their historic periods and types, including (but not limited to) Late Antique, Insular, Carolingian manuscripts, Ottonian manuscripts, Romanesque manuscripts, Gothic manuscripts, and Renaissance manuscripts. There are a few examples from later periods. The type of book most often heavily and richly illuminated, sometimes known as a "display book", varied between periods. In the first millennium, these were most likely to be Gospel Books, such as the Lindisfarne Gospels and the Book of Kells. The Romanesque period saw the creation of many large illuminated complete Bibles – one in Sweden requires three librarians to lift it. Many Psalters were also heavily illuminated in both this and the Gothic period. Single cards or posters of vellum, leather or paper were in wider circulation with short stories or legends on them about the lives of saints, chivalry knights or other mythological figures, even criminal, social or miraculous occurrences; popular events much freely used by story tellers and itinerant actors to support their plays. Finally, the Book of Hours, very commonly the personal devotional book of a wealthy layperson, was often richly illuminated in the Gothic period. Many were illuminated with miniatures, decorated initials and floral borders. Paper was rare and most Books of Hours were composed of sheets of parchment made from skins of animals, usually sheep or goats. Other books, both liturgical and not, continued to be illuminated at all periods.

The Byzantine world produced manuscripts in its own style, versions of which spread to other Orthodox and Eastern Christian areas. The Muslim World and in particular the Iberian Peninsula, with their traditions of literacy uninterrupted by the Middle Ages, were instrumental in delivering ancient classic works to the growing intellectual circles and universities of Western Europe all through the 12th century, as books were produced there in large numbers and on paper for the first time in Europe, and with them full treatises on the sciences, especially astrology and medicine where illumination was required to have profuse and accurate representations with the text.

The Gothic period, which generally saw an increase in the production of these artifacts, also saw more secular works such as chronicles and works of literature illuminated. Wealthy people began to build up personal libraries; Philip the Bold probably had the largest personal library of his time in the mid-15th century, is estimated to have had about 600 illuminated manuscripts, whilst a number of his friends and relations had several dozen.

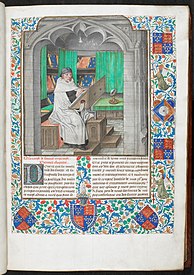

Up to the 12th century, most manuscripts were produced in monasteries in order to add to the library or after receiving a commission from a wealthy patron. Larger monasteries often contained separate areas for the monks who specialized in the production of manuscripts called a scriptorium. Within the walls of a scriptorium were individualized areas where a monk could sit and work on a manuscript without being disturbed by his fellow brethren. If no scriptorium was available, then "separate little rooms were assigned to book copying; they were situated in such a way that each scribe had to himself a window open to the cloister walk".[2]

By the 14th century, the cloisters of monks writing in the scriptorium had almost fully given way to commercial urban scriptoria, especially in Paris, Rome and the Netherlands.[3] While the process of creating an illuminated manuscript did not change, the move from monasteries to commercial settings was a radical step. Demand for manuscripts grew to an extent that Monastic libraries began to employ secular scribes and illuminators.[4] These individuals often lived close to the monastery and, in instances, dressed as monks whenever they entered the monastery, but were allowed to leave at the end of the day. In reality, illuminators were often well known and acclaimed and many of their identities have survived.[5]

First, the manuscript was "sent to the rubricator, who added (in red or other colors) the titles, headlines, the initials of chapters and sections, the notes and so on; and then – if the book was to be illustrated – it was sent to the illuminator".[2] In the case of manuscripts that were sold commercially, the writing would "undoubtedly have been discussed initially between the patron and the scribe (or the scribe’s agent,) but by the time that the written gathering were sent off to the illuminator there was no longer any scope for innovation".[6]

Techniques[]

Illumination was a complex and frequently costly process. It was usually reserved for special books: an altar Bible, for example. Wealthy people often had richly illuminated "books of hours" made, which set down prayers appropriate for various times in the liturgical day.

In the early Middle Ages, most books were produced in monasteries, whether for their own use, for presentation, or for a commission. However, commercial scriptoria grew up in large cities, especially Paris, and in Italy and the Netherlands, and by the late 14th century there was a significant industry producing manuscripts, including agents who would take long-distance commissions, with details of the heraldry of the buyer and the saints of personal interest to him (for the calendar of a Book of hours). By the end of the period, many of the painters were women, perhaps especially in Paris.

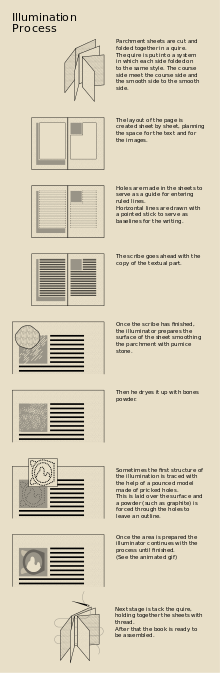

Text[]

The text was usually written before the manuscripts were illuminated. Sheets of parchment or vellum were cut down to the appropriate size. These sizes ranged from 'Atlantic' Bibles large stationary works to small hand held works.[8] After the general layout of the page was planned (including the initial capitals and borders), the page was lightly ruled with a pointed stick, and the scribe went to work with ink-pot and either sharpened quill feather or reed pen. The script depended on local customs and tastes. The sturdy Roman letters of the early Middle Ages gradually gave way to scripts such as Uncial and half-Uncial, especially in the British Isles, where distinctive scripts such as insular majuscule and insular minuscule developed. Stocky, richly textured blackletter was first seen around the 13th century and was particularly popular in the later Middle Ages.

Prior to the days of such careful planning, "A typical black-letter page of these Gothic years would show a page in which the lettering was cramped and crowded into a format dominated by huge ornamented capitals that descended from uncial forms or by illustrations".[9] To prevent such poorly made manuscripts and illuminations from occurring a script was typically supplied first, "and blank spaces were left for the decoration. This pre-supposes very careful planning by the scribe even before he put pen to parchment". If the scribe and the illuminator were separate labors the planning period allowed for adequate space to be given to each individual.

The process of illumination[]

I. Graphite powder dots create the outline II. Silverpoint drawings are sketched III. Illustration is retraced with ink IV. The surface is prepared for the application of gold leaf V. Gold leaf is laid down VI. Gold leaf is burnished to make it glossy and reflective VII. Decorative impressions are made to adhere the leaf VIII. Base colors are applied IX. Darker tones are used to give volume X. Further details are drawn XI. Lighter colors are used to add particulars XII. Ink borders are traced to finalize the illumination

The following steps outline the detailed labor involved to create the illuminations of one page of a manuscript:

- Silverpoint drawing of the design were executed

- Burnished gold dots applied

- The application of modulating colors

- Continuation of the previous three steps in addition to the outlining of marginal figures

- The penning of a rinceau appearing in the border of a page

- The final step, the marginal figures are painted[10]

The illumination and decoration was normally planned at the inception of the work, and space reserved for it. However, the text was usually written before illumination began. In the Early Medieval period the text and illumination were often done by the same people, normally monks, but by the High Middle Ages the roles were typically separated, except for routine initials and flourishes, and by at least the 14th century there were secular workshops producing manuscripts, and by the beginning of the 15th century these were producing most of the best work, and were commissioned even by monasteries. When the text was complete, the illustrator set to work. Complex designs were planned out beforehand, probably on wax tablets, the sketch pad of the era. The design was then traced or drawn onto the vellum (possibly with the aid of pinpricks or other markings, as in the case of the Lindisfarne Gospels). Many incomplete manuscripts survive from most periods, giving us a good idea of working methods.

At all times, most manuscripts did not have images in them. In the early Middle Ages, manuscripts tend to either be display books with very full illumination, or manuscripts for study with at most a few decorated initials and flourishes. By the Romanesque period many more manuscripts had decorated or historiated initials, and manuscripts essentially for study often contained some images, often not in color. This trend intensified in the Gothic period, when most manuscripts had at least decorative flourishes in places, and a much larger proportion had images of some sort. Display books of the Gothic period in particular had very elaborate decorated borders of foliate patterns, often with small drolleries. A Gothic page might contain several areas and types of decoration: a miniature in a frame, a historiated initial beginning a passage of text, and a border with drolleries. Often different artists worked on the different parts of the decoration.

Paints[]

While the use of gold is by far one of the most captivating features of illuminated manuscripts, the bold use of varying colors provided multiple layers of dimension to the illumination. From a religious perspective, "the diverse colors wherewith the book is illustrated, not unworthily represent the multiple grace of heavenly wisdom."[2]

The medieval artist's palette was broad; a partial list of pigments is given below. In addition, unlikely-sounding substances such as urine and earwax were used to prepare pigments.[11]

| Color | Source(s) |

|---|---|

| Red | Insect-based colors, including:

Chemical- and mineral-based colors, including:

|

| Yellow | Plant-based colors, such as:

Mineral-based colors, including:

|

| Green |

|

| Blue | Plant-based substances such as:

Chemical- and mineral-based colors, including:

|

| White |

|

| Black |

|

| Gold |

|

| Silver |

|

Gilding[]

On the strictest definition, a manuscript is not considered "illuminated" unless one or many illuminations contained metal, normally gold leaf or shell gold paint, or at least was brushed with gold specks. Gold leaf was from the 12th century usually polished, a process known as burnishing. The inclusion of gold alludes to many different possibilities for the text. If the text is of religious nature lettering in gold is a sign of exalting the text. In the early centuries of Christianity, “Gospel manuscripts were sometimes written entirely in gold".[12] The gold ground style, with all or most of the background in gold, was taken from Byzantine mosaics and icons. Aside from adding rich decoration to the text, scribes during the time considered themselves to be praising God with their use of gold. Furthermore, gold was used if a patron who had commissioned a book to be written wished to display the vastness of his riches. Eventually, the addition of gold to manuscripts became so frequent, "that its value as a barometer of status with the manuscript was degraded".[13] During this time period the price of gold had become so cheap that its inclusion in an illuminated manuscript accounted for only a tenth of the cost of production.[14] By adding richness and depth to the manuscript, the use of gold in illuminations created pieces of art that are still valued today.

The application of gold leaf or dust to an illumination is a very detailed process that only the most skilled illuminators can undertake and successfully achieve. The first detail an illuminator considered when dealing with gold was whether to use gold leaf or specks of gold that could be applied with a brush. When working with gold leaf the pieces would be hammered and thinned until they were "thinner than the thinnest paper".[14] The use of this type of leaf allowed for numerous areas of the text to be outlined in gold. There were several ways of applying gold to an illumination one of the most popular included mixing the gold with stag's glue and then "pour it into water and dissolve it with your finger".[15] Once the gold was soft and malleable in the water it was ready to be applied to the page. Illuminators had to be very careful when applying gold leaf to the manuscript. Gold leaf is able to "adhere to any pigment which had already been laid, ruining the design, and secondly the action of burnishing it is vigorous and runs the risk of smudging any painting already around it."

Patrons[]

Monasteries produced manuscripts for their own use; heavily illuminated ones tended to be reserved for liturgical use in the early period, while the monastery library held plainer texts. In the early period manuscripts were often commissioned by rulers for their own personal use or as diplomatic gifts, and many old manuscripts continued to be given in this way, even into the Early Modern period. Especially after the book of hours became popular, wealthy individuals commissioned works as a sign of status within the community, sometimes including donor portraits or heraldry: "In a scene from the New Testament, Christ would be shown larger than an apostle, who would be bigger than a mere bystander in the picture, while the humble donor of the painting or the artist himself might appear as a tiny figure in the corner."[16][17] The calendar was also personalized, recording the feast days of local or family saints. By the end of the Middle Ages many manuscripts were produced for distribution through a network of agents, and blank spaces might be reserved for the appropriate heraldry to be added locally by the buyer.

Displaying the amazing detail and richness of a text, the addition of illumination was never an afterthought. The inclusion of illumination is twofold, it added value to the work, but more importantly it provides pictures for the illiterate members of society to "make the reading seem more vivid and perhaps more credible".[18]

Gallery[]

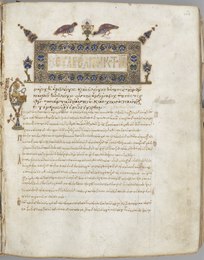

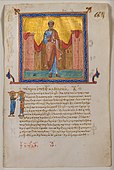

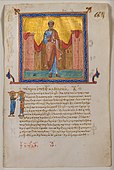

Leaf from a Byzantine Psalter and New Testament; 1079; ink, tempera and gold on vellum; sheet: 16.3 x 10.9 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, Ohio, USA)

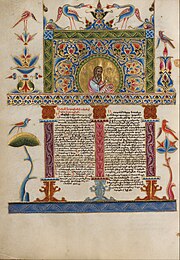

Definitions of Philosophy of David the Invincible; 1280; vellum; Matenadaran (Yerevan, Armenia)

Detail from Bifolium with Christ in Majesty in an Initial A, from an Antiphonary; circa 1405; tempera, gold, and ink on parchment; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

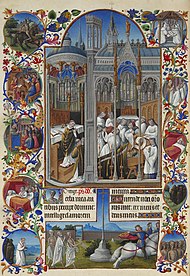

Leaf from a Book of Hours; circa 1460; ink, tempera and gold on vellum; leaf: 19.7 x 14.3 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art

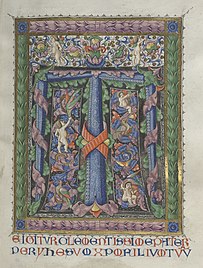

Detail of a L from Benedictine Antiphonary; by Belbello da Pavia; circa 1467–1470; tempera, gold, and ink on parchment, binding: leather over wood boards with copper alloy corner mounts and bosses; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Leaf from a Gradual: Initial P with the Nativity; 1495; ink, tempera and gold on vellum; each leaf: 59.8 x 4.1 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art

Hours of Queen Isabella the Catholic, Queen of Spain; circa 1500; ink, tempera, and gold on vellum; codex: 22.5 x 15.2 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art

Farnese Hours, an example of a Renaissance illuminated page; by Giulio Clovio; 1537–1546; illumination on parchment; height: 17.1 cm, width: 11.1 cm; Morgan Library & Museum (New York City)

Four Evangelists; 1572–1585; height: 41.3 cm, width: 27.7 cm; from Italy, probably Rome; Morgan Library & Museum

Al-Quran, 1591–92, from Safavid Iran; Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum (Istanbul)

See also[]

References[]

- ^ The untypically early 11th century Missal of Silos is from Spain, near to Muslim paper manufacturing centres in Al-Andaluz. Textual manuscripts on paper become increasingly common, but the more expensive parchment was mostly used for illuminated manuscripts until the end of the period.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Putnam A.M., Geo. Haven. Books and Their Makers During The Middle Ages. Vol. 1. New York: Hillary House, 1962. Print.

- ^ De Hamel, 45

- ^ De Hamel, 57

- ^ De Hamel, 65

- ^ De Hamel, Christopher. Medieval Craftsmen: Scribes and Illuminations. Buffalo: University of Toronto, 1992. p. 60.

- ^ "Getijdenboek van Alexandre Petau". lib.ugent.be. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ de Hamel, Christopher (2001). The British Library Guide To Manuscript Illumination History and Techniques. Toronto: British Library. p. 35. ISBN 0-8020-8173-8.

- ^ Anderson, Donald M. The Art of Written Forms: The Theory and Practice of Calligraphy. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc, 1969. Print.

- ^ Calkins, Robert G. "Stages of Execution: Procedures of Illumination as Revealed in an Unfinished Book of Hours." International Center of Medieval Art 17.1 (1978): 61–70. JSTOR.org. Web. 17 April 2010. <https://www.jstor.org/stable/766713>

- ^ Iberian manuscripts (pigments) Archived 29 March 2003 at archive.today

- ^ De Hamel, Christopher. The British Library Guide to Manuscript Illumination: History and Techniques. Toronto: University of Toronto, 2001. Print,52.

- ^ De Hamel, Christopher. Medieval Craftsmen: Scribes and Illuminations. Buffalo: University of Toronto, 1992. Print,49.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brehier, Louis. "Illuminated Manuscripts". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol.9. New York: Robert Appelton Company, 1910. 17 April 2010 http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09620a.htm, page 45.

- ^ Blondheim, D.S. "An Old Portuguese Work on Manuscript Illumination." The Jewish Quarterly Review, New Series 19.2 (1928): 97–135. JSTOR. Web. 17 April 2010. <https://www.jstor.org/stable/1451766>.

- ^ Hamel, Christopher de (29 December 2001). The British Library Guide to Manuscript Illumination: History and Techniques (1 ed.). University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division. p. 20. ISBN 0-8020-8173-8.

- ^ "Heraldry". Glossary for Illuminated Manuscripts. British Library. n.d. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ Jones, Susan. "Manuscript Illumination in Northern Europe". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/manu/hd_manu.htm (October 2002)

Further reading[]

- Alexander, Jonathan A.G., Medieval Illuminators and their Methods of Work, 1992, Yale UP, ISBN 0300056893

- Coleman, Joyce, Mark Cruse, and Kathryn A. Smith, eds. The Social Life of Illumination: Manuscripts, Images, and Communities in the Late Middle Ages (Series: Medieval Texts and Cultures in Northern Europe, vol. 21. Turnhout: Brepols Publishing, 2013). xxiv + 552 pp online review

- Calkins, Robert G. Illuminated Books of the Middle Ages. 1983, Cornell University Press, ISBN 0500233756

- De Hamel, Christopher. A History of Illuminated Manuscript (Phaidon, 1986)

- De Hamel, Christopher. Medieval Craftsmen: Scribes and Illuminations. Buffalo: University of Toronto, 1992.

- Kren, T. & McKendrick, Scot (eds), Illuminating the Renaissance – The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe, Getty Museum/Royal Academy of Arts, 2003, ISBN 1-903973-28-7

- Liepe, Lena. Studies in Icelandic Fourteenth Century Book Painting, Reykholt: Snorrastofa, rit. vol. VI, 2009.

- Morgan, Nigel J., Stella Panayotova, and Martine Meuwese. Illuminated Manuscripts in Cambridge: A Catalogue of Western Book Illumination in the Fitzwilliam Museum and the Cambridge Colleges (London : Harvey Miller Publishers in conjunction with the Modern Humanities Association. 1999– )

- Pächt, Otto, Book Illumination in the Middle Ages (trans fr German), 1986, Harvey Miller Publishers, London, ISBN 0199210608

- Rudy, Kathryn M. (2016), Piety in Pieces: How Medieval Readers Customized their Manuscripts, Open Book Publishers, doi:10.11647/OBP.0094, ISBN 9781783742356

- Wieck, Roger. "Folia Fugitiva: The Pursuit of the Illuminated Manuscript Leaf". The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery, Vol. 54, 1996.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Illuminated manuscripts. |

- Thompson, Edward M. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 14 (11th ed.). pp. 312–320.

Images[]

- Illuminated Manuscripts in the J. Paul Getty Museum – Los Angeles

- Illuminating the Manuscript Leaves Digitized illuminated manuscripts from the University of Louisville Libraries

- 15 pages of illuminated manuscripts from the Ball State University Digital Media Repository

- Digitized Illuminated Manuscripts – Complete sets of high-resolution archival images from the Walters Art Museum

- Collection of Armenian Illuminated Manuscripts – A full collection with high resolution images of Armenian Illuminated Manuscripts

Resources[]

- UCLA Library Special Collections collection of Medieval and Renaissance manuscripts

- British Library, catalogue of illuminated manuscripts

- Collection of illuminated manuscripts. From the Koninklijke Bibliotheek and Museum Meermanno-Westreenianum in The Hague.

- Demonstration of the production of an illuminated manuscript from the Fitzwilliam, Cambridge (Flash player needed)

- CORSAIR. Thousands of digital images from the Morgan Library's renowned collection of medieval and Renaissance manuscripts

- Manuscript Miniatures, a collection of illustrations from manuscripts made before 1450

- Illuminated manuscripts

- Books by type

- Book arts

- Book design

- Book terminology

- Christian genres

- Gilding

- Manuscripts

- Textual scholarship

- Western art