Immigration to New Zealand

Migration to New Zealand began with Polynesian settlement in New Zealand, then uninhabited, about 1250 to 1280. European migration provided a major influx following the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840. Subsequent immigration has been chiefly from the British Isles, but also from continental Europe, the Pacific, the Americas and Asia.

Polynesian settlement[]

Polynesians in the South Pacific were the first to discover the landmass of New Zealand. Eastern Polynesian explorers had settled in New Zealand by approximately the thirteenth century CE with most evidence pointing to an arrival date of about 1280. Their arrival gave rise to the Māori culture and the Māori language, both unique to New Zealand, although very closely related to analogues in other parts of Eastern Polynesia. Evidence from Wairau Bar and the Chatham Islands shows that the Polynesian colonists maintained many parts of their east Polynesian culture such as burial customs for at least 50 years. Especially strong resemblances link Māori to the languages and cultures of the Cook and Society Islands, which are regarded as the most likely places of origin.[1] Moriori settled the Chatham Islands during the 15th century from mainland New Zealand.

European settlement[]

Due to New Zealand's geographic isolation, several centuries passed before the next phase of settlement, the arrival of Europeans (beginning with Abel Tasman's visit in 1642). Only then did the original inhabitants need to distinguish themselves from the new arrivals, using the adjective "māori" which means "ordinary" or "indigenous" which later became a noun although the term New Zealand native was common until about 1890. Māori thought of their tribe (iwi) as a nation.[citation needed]

James Cook claimed New Zealand for Britain on his arrival in 1769. The establishment of British colonies in Australia from 1788 and the boom in whaling and sealing in the Southern Ocean brought many Europeans to the vicinity of New Zealand, with some deciding to settle. Whalers and sealers were often itinerant and the first real settlers were missionaries and traders in the Bay of Islands area from 1809. By 1830 there was a population of about 800 non Māori which included a total of about 200 runaway convicts and seamen who often married into the Māori community.[citation needed] The seamen often lived in New Zealand for a short time before joining another ship a few months later. In 1839 there were 1100 Europeans living in the North Island. Regular outbreaks of extreme violence mainly between Māori hapu, known as the Musket Wars, resulted in the deaths of between 20,000 and 50,000 Māori up until 1843.[citation needed] Violence against European shipping, cannibalism and the lack of established law and order made settling in New Zealand a risky prospect. By the late 1830s many Māori were nominally Christian and had freed many of the Māori slaves that had been captured during the Musket Wars. By this time, many Māori, especially in the north, could read and write Māori and to a lesser extent English.

Migration from 1840[]

European migration has resulted in a deep legacy being left on the social and political structures of New Zealand. Early visitors to New Zealand included whalers, sealers, missionaries, mariners, and merchants, attracted to natural resources in abundance.

New Zealand was administered from New South Wales from 1788[dubious ] and the first permanent settlers were Australians. Some were escaped convicts, and others were ex-convicts that had completed their sentences. Smaller numbers came directly from Great Britain, Ireland, Germany (forming the next biggest immigrant group after the British and Irish),[2] France, Portugal, the Netherlands, Denmark, The United States, and Canada.

In 1840 representatives of the British Crown signed the Treaty of Waitangi with 240 Māori chiefs throughout New Zealand, motivated by plans for a French colony at Akaroa and land purchases by the New Zealand Company in 1839. British sovereignty was then proclaimed over New Zealand in May 1840 and by 1841 New Zealand had ceased being an Australian colony.

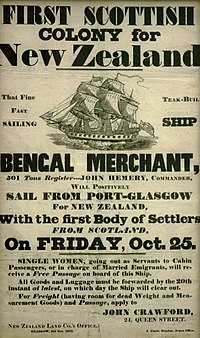

Following the formalising of sovereignty, organised and structured flow of migrants from Great Britain and Ireland began. Government-chartered ships like the clipper Gananoque and the Glentanner carried immigrants to New Zealand. Typically clipper ships left British ports such as London and travelled south through the central Atlantic to about 43 degrees south to pick up the strong westerly winds that carried the clippers well south of South Africa and Australia. Ships would then head north once in the vicinity of New Zealand. The Glentanner migrant ship of 610 tonnes made two runs to New Zealand and several to Australia carrying 400 tonne of passengers and cargo. Travel time was about 3 to 3+1⁄2 months to New Zealand. Cargo carried on the Glentanner for New Zealand included coal, slate, lead sheet, wine, beer, cart components, salt, soap and passengers' personal goods. On the 1857 passage the ship carried 163 official passengers, most of them government assisted. On the return trip the ship carried a wool cargo worth 45,000 pounds.[3] In the 1860s discovery of gold started a gold rush in Otago. By 1860 more than 100,000 British and Irish settlers lived throughout New Zealand. The Otago Association actively recruited settlers from Scotland, creating a definite Scottish influence in that region, while the Canterbury Association recruited settlers from the south of England, creating a definite English influence over that region.[4]

In the 1860s most migrants settled in the South Island due to gold discoveries and the availability of flat grass covered land for pastoral farming. The low number of Māori (about 2,000) and the absence of warfare gave the South Island many advantages. It was only when the New Zealand wars ended that the North Island again became an attractive destination. In order to attract settlers to the North Island the Government and Auckland Provisional government initiated the Waikato Immigration Scheme which ran from 1864 and 1865.[5][6] The central government originally intended to bring about 20,000 immigrants to the Waikato from the British Isles and the Cape Colony in South Africa to consolidate the government position after the wars and develop the Waikato area for European settlement. The immigration scheme settlers were allocated quarter-acre town sections and ten-acre rural sections. They were required to work on and improve the sections for two years after which a Crown Grant would be issued, giving them ownership.[7] In all, 13 ships travelled to New Zealand under the scheme, arriving from London, Glasgow and Cape Town.[8]

In the 1870s, Premier Julius Vogel borrowed millions of pounds from Britain to help fund capital development such as a nationwide rail system, lighthouses, ports and bridges, and encouraged mass migration from Britain. By 1870 the non-Māori population reached over 250,000.[9]

Other smaller groups of settlers came from Germany, Scandinavia, and other parts of Europe as well as from China and India, but British, Scottish and Irish settlers made up the vast majority, and did so for the next 150 years. Today, the majority of New Zealanders have some sort of British, Scottish, Welsh and Irish ancestry. This comes with last names (mainly British, Irish, and Scottish) as well.

Between 1881 and the 1920s, the New Zealand Parliament passed legislation that intended to limit Asiatic migration to New Zealand, and prevented Asians from naturalising.[10] In particular, the New Zealand government levied a poll tax on Chinese immigrants up until the 1930s. New Zealand finally abolished the poll tax in 1944. Large numbers of Dalmatians fled from the Austro- Hungarian empire to settle in New Zealand around 1900. They settled mainly in west Auckland and often worked to establish vineyards and orchards or worked on gum fields in Northland.

An influx of Jewish refugees from central Europe came in the 1930s.

Many of the persons of Polish descent in New Zealand arrived as orphans via Siberia and Iran during World War II.

Post World War II migration[]

With the various agencies of the United Nations dealing with humanitarian efforts following the Second World War, New Zealand accepted about 5,000 refugees and displaced persons from Europe, and more than 1,100 Hungarians between 1956 and 1959 (see Refugees in New Zealand). The post-WWII immigration included more people from Greece, Italy, Poland and the former Yugoslavia.

New Zealand limited immigration to those who would meet a labour shortage in New Zealand. To encourage those to come, the government introduced free and assisted passages in 1947, a scheme expanded by the National Party administration in 1950. However, when it became clear that not enough skilled migrants would come from the British Isles alone, recruitment began in Northern European countries. New Zealand signed a bilateral agreement for skilled migrants with the Netherlands, and a large number[clarification needed] of Dutch immigrants arrived in New Zealand. Others came in the 1950s from Denmark, Germany, Switzerland and Austria to meet needs in specialised occupations.

By the 1960s, the policy of excluding people based on nationality yielded a population overwhelmingly European in origin. By the mid-1960s, a desire for cheap unskilled labour led to ethnic diversification. In the 1950s and 1960s, New Zealand encouraged migrants from the South Pacific. The country had a large demand for unskilled labour in the manufacturing sector. As long as this demand continued, migration was accepted from the South Pacific, and many temporary workers overstayed their visas. Consequently, the Pacific Island population in New Zealand had grown to 45,413 by 1971.[11] The economic crisis of the early 1970s led to increased crime, unemployment and other social ailments, which disproportionately affected the Pacific Islander community.[12] From 1974 to 1979 Dawn Raids were carried out by police to remove overstayers, most of whom were Pacific Islanders.

In May 2008, Massey University economist Dr Greg Clydesdale released to the news media an extract of a report, Growing Pains, Evaluations and the Cost of Human Capital, which saw Pacific Islanders as "forming an underclass".[13] The report, written by Dr Clydesdale for the Academy of World Business, Marketing & Management Development 2008 Conference in Brazil, and based on data from various government departments, provoked highly controversial debate. Pacific Islands community leaders and academic peer reviewers strongly criticised the report, while a provisional review was lodged by Race Relations Commissioner Joris de Bres.[14][15]

A record number of migrants arrived in the 1970s; 70,000, for example, during 1973–1974. While these numbers represent many ethnicities, New Zealand had an underlying preference for migrants from "traditional sources", namely Britain, Europe and Northern America, due to similarities of language and culture.[16] [17]

Introduction of points-based systems[]

Along with New Zealand adopting a radical direction of economic practice, Parliament passed a new Immigration Act into law in 1987. This would end the preference for migrants from Britain, Europe or Northern America based on their race, and instead classify migrants on their skills, personal qualities, and potential contribution to New Zealand economy and society. The introduction of the points-based system came under the National government, which pursued this policy-change even more than the previous Labour Party administration. This system resembled that of Canada, and came into effect in 1991. Effectively the New Zealand Immigration Service ranks the qualities sought in the migrants and gives them a priority using a points-based scale. In 2010 the new Immigration Act replaced all existing protocols and procedures.

The Government published the results of an immigration review in December 2006.[18]

Regulations provide that immigrants must be of good character.[19]

New migrant groups[]

Source: New Zealand Department of Labour[20]

This policy resulted in a wide variety of ethnicities in New Zealand, with people from over 120 countries represented. Between 1991 and 1995 the numbers of those given approval grew rapidly: 26,000 in 1992; 35,000 in 1994; 54,811 in 1995. The minimum target for residency approval was set[by whom?] at 25,000. The number approved was almost twice what was targeted. The Labour-led governments of 1999–2008 made no change to the Immigration Act 1987, although some changes were made[by whom?] to the 1991 policy. In particular, the minimum IELTS level for skilled migrants was raised[by whom?] from 5.5 to 6.5 in 2002, following concerns that immigrants who spoke English as a second language encountered difficulty getting jobs in their chosen fields.[21] Since then, migration from Britain and South Africa has increased, at the expense of immigration from Asia. However, a study-for-residency programme for foreign university students has mitigated this imbalance somewhat.[citation needed]

By 2005, New Zealand accepted 60% of the applicants under the Skilled/Business category that awarded points for qualifications and work experience, or business experience and funds they had available. From 1 Aug 2007, NZD$2.5 million is the minimum for the Active Investor Migrant Category.

Changes to the point system have also given more weight to job offers as compared to educational degrees. Some Aucklanders cynically joke that most taxi drivers in Auckland tend to be highly qualified engineers or doctors who are unable to then find jobs in their fields once in the country.[22]

Recent years[]

In 2004–2005 Immigration New Zealand set a target of 45,000, representing 1.5% of the total population. However, the net effect was a population decline, since more left than arrived. 48,815 arrived, and overall the population was 10,000 or 0.25% less than the previous year. Overall though, New Zealand has one of the highest populations of foreign born citizens. In 2005, almost 20% of New Zealanders were born overseas, one of the highest percentages of any country in the world. The Department of Labour's sixth annual Migration Trends report shows a 21 per cent rise in work permits issued in the 2005/06-year compared with the previous year. Nearly 100,000 people were issued work permits to work in sectors ranging from IT to horticulture in the 2005/06-year. This compares with around 35,000 work permits issued in 1999–2000. Around 52,000 people were approved for permanent New Zealand residence in 2005/06. Over 60 per cent were approved under the skilled or business categories.

Other migrant quotas[]

New Zealand accepts 1000 refugees per year (set to grow to 1500 by 1 July 2020) in co-operation with the UNHCR with a strong focus on the Asia-Pacific region.[23] As part of the Pacific Access Category, 650 citizens come from Fiji, Tuvalu, Kiribati, and Tonga. 1,100 Samoan citizens come under the Samoan Quota scheme. Once resident, these people can apply to bring other family members to New Zealand under the Family Sponsored stream. Any migrant accepted under these schemes receives permanent residency in New Zealand.

Contemporary developments in immigration policy[]

Immigration Advisers Licensing Act 2007[]

Effective in New Zealand from 4 May 2007, the Immigration Advisers Licensing Act requires anyone providing immigration advice to be licensed. It also established the Immigration Advisers Authority to manage the licensing process, both in New Zealand and offshore.

From 4 May 2009 it became mandatory for immigration advisers practising in New Zealand to be licensed unless they are exempt.[24] The introduction of mandatory licensing for New Zealand-based immigration advisers was designed to protect migrants from unscrupulous operators and provide support for licensed advisers.

The licensing managed by the Immigration Advisers Authority Official website establishes and monitors industry standards and sets requirements for continued professional development. As an independent body, the Authority can prosecute unlicensed immigration advisers. Penalties include up to seven years imprisonment and/or fines up to $NZ100,000 for offenders, as well as the possibility of court-ordered reparation payments. It can refer complaints made against licensed advisers to an Independent Tribunal, i.e. Immigration Advisers Complaints & Disciplinary Tribunal.

The Immigration Advisers Authority does not handle immigration applications or inquiries. These are managed by Immigration New Zealand.

Immigration Act 2009[]

Statements by the government in the mid 2000s emphasised that New Zealand must compete for its share of skilled and talented migrants, and David Cunliffe, the former immigration minister, has argued that New Zealand was "in a global race for talent and we must win our share".[25] With this in mind, a bill (over 400 pages long) was prepared[by whom?] which was sent[by whom?] to parliament in April 2007. It follows a review of the immigration act. The bill aims to make the process more efficient, and achieves this by giving more power to immigration officers. Rights of appeal were to be streamlined into a single appeal tribunal. Furthermore, any involvement of the Human Rights Commission in matters of immigration to New Zealand would be removed (Part 11, Clause 350).

The new Immigration Act, which passed into law in 2009 replacing the 1987 Act, is aimed to enhance border security and improve the efficiency of the immigration services. Key aspects of the new Act include the ability to use biometrics, a new refugee and protection system, a single independent appeals tribunal and a universal visa system.[26]

Further developments[]

As of March 2012, a draft paper leaked to the New Zealand Labour Party shows Immigration New Zealand is planning to create a two-tier system which will favour wealthy immigrants over poor ones who speak little or no English. This means that applications from parents sponsored by their higher income children, or those who bring a guaranteed income or funds, would be processed faster than other applications.[27][28]

During the New Zealand general election, 2017 the New Zealand First party launched its campaign in Palmerston North on 25 June 2017. Announced policies including cutting net immigration to 10,000 per year.[29] NZ First leader Winston Peters said that unemployed New Zealanders will be trained to take jobs as the number is reduced, and the number of older immigrants will be limited, with more bonded to the regions.[30]

According to Statistics New Zealand estimates, New Zealand's net migration (long-term arrivals minus long-term departures) in the June 2016/17 year was 72,300.[31] That was up from 38,300 in the June 2013/14 year.[32] Of those migrants specifying a region of settlement, 61 percent settled in the Auckland region.[33]

2021 Afghan evacuation[]

Following the 2021 Taliban offensive which led to a significant exodus of Afghan refugees, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade suspended the processing of residency applications from Afghan nationals in late August 2021, citing the "rapidly deteriorating situation" in Afghanistan and a "diminishing window for evacuations. The Government has instead prioritised the evacuation of New Zealand citizens, permanent residents and Afghans at risk due to their "association with New Zealand."[34] The Government's decision to suspend the processing of Afghan residency visa applications was criticised by human rights advocates and Afghan migrants. Former Afghan interpreter Diamond Kazimi stated that 200 Afghan families that had assisted New Zealand Defence Force personnel in Afghanistan were still waiting for their visa applications to be processed. By 26 August, a Royal New Zealand Air Force C-130 Hercules had made two evacuation flights from Kabul.[35]

Public opinion[]

As in some other countries, immigration can become a contentious issue; the topic has provoked debate from time to time in New Zealand.[citation needed]

As early as the 1870s, political opponents fought against Vogel's immigration plans.[36]

The political party New Zealand First (founded in 1993) has frequently criticised immigration on economic, social and cultural grounds.[citation needed] New Zealand First leader Winston Peters has on several occasions characterised the rate of Asian immigration into New Zealand as too high; in 2004, he stated: "We are being dragged into the status of an Asian colony and it is time that New Zealanders were placed first in their own country."[37] On 26 April 2005, he said: "Māori will be disturbed to know that in 17 years' time they will be outnumbered by Asians in New Zealand" – an estimate disputed by Statistics New Zealand, the government's statistics bureau. Peters quickly rebutted that Statistics New Zealand had underestimated the growth-rate of the Asian community in the past.[38]

In April 2008, then deputy New Zealand First Party leader Peter Brown drew widespread attention after voicing similar views and expressing concern at the increase in New Zealand's ethnic Asian population: "We are going to flood this country with Asian people with no idea what we are going to do with them when they come here."[39] "The matter is serious. If we continue this open door policy there is real danger we will be inundated with people who have no intention of integrating into our society. The greater the number, the greater the risk. They will form their own mini-societies to the detriment of integration and that will lead to division, friction and resentment."[40]

Statistics[]

| Country | Gross arrivals | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| 19,549 | 23,275 | 25,273 | 25,783 | 24,950 | 21,562 | 16,537 | |

| 13,938 | 13,680 | 13,379 | 14,373 | 15,017 | 13,246 | 11,185 | |

| 1,285 | 1,669 | 2,404 | 4,563 | 5,275 | 5,528 | 9,174 | |

| 6,704 | 11,303 | 14,490 | 10,255 | 9,030 | 8,991 | 8,957 | |

| 8,182 | 9,515 | 11,036 | 12,461 | 11,993 | 10,460 | 8,338 | |

| 2,660 | 3,890 | 5,393 | 4,918 | 5,223 | 4,865 | 5,597 | |

| 3,894 | 3,900 | 4,297 | 4,300 | 5,010 | 4,683 | 4,388 | |

| 2,374 | 3,334 | 3,767 | 4,227 | 4,392 | 4,085 | 3,710 | |

| 3,295 | 3,564 | 3,906 | 4,459 | 4,309 | 3,905 | 3,220 | |

| 1,870 | 2,166 | 2,463 | 2,508 | 2,671 | 2,969 | 2,733 | |

| 1,846 | 1,796 | 1,977 | 2,521 | 2,812 | 2,882 | 2,708 | |

| 1,947 | 2,126 | 2,273 | 2,456 | 2,415 | 2,371 | 2,507 | |

| 1,421 | 1,726 | 1,915 | 1,957 | 2,124 | 1,961 | 1,874 | |

| 1,210 | 1,361 | 1,470 | 1,983 | 1,790 | 1,630 | 1,681 | |

| 1,661 | 1,240 | 1,148 | 1,070 | 1,139 | 1,132 | 1,100 | |

| 539 | 610 | 730 | 860 | 1,114 | 1,001 | 1,075 | |

| 934 | 1,021 | 1,367 | 1,429 | 1,461 | 1,329 | 1,074 | |

| 523 | 665 | 752 | 989 | 1,146 | 1,160 | 1,065 | |

| 1,083 | 1,177 | 1,287 | 1,535 | 1,562 | 1,477 | 1,064 | |

| 634 | 606 | 880 | 908 | 1,078 | 974 | 1,034 | |

| Total | 93,965 | 109,317 | 121,937 | 127,305 | 131,566 | 122,010 | 110,473 |

| Country | 2001 census | 2006 census | 2013 census | 2018 census[44] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| 2,890,869 | 80.54 | 2,960,217 | 77.09 | 2,980,824 | 74.85 | 3,370,122 | 72.60 | |

| 178,203 | 4.96 | 202,401 | 5.27 | 215,589 | 5.41 | 210,915 | 4.54 | |

| 38,949 | 1.09 | 78,117 | 2.03 | 89,121 | 2.24 | 132,906 | 2.86 | |

| 20,892 | 0.58 | 43,341 | 1.13 | 67,176 | 1.69 | 117,348 | 2.53 | |

| 56,259 | 1.57 | 62,742 | 1.63 | 62,712 | 1.57 | 75,696 | 1.63 | |

| 26,061 | 0.73 | 41,676 | 1.09 | 54,276 | 1.36 | 71,382 | 1.54 | |

| 10,134 | 0.28 | 15,285 | 0.40 | 37,299 | 0.94 | 67,632 | 1.46 | |

| 25,722 | 0.72 | 37,746 | 0.98 | 52,755 | 1.32 | 62,310 | 1.34 | |

| 47,118 | 1.31 | 50,649 | 1.32 | 50,661 | 1.27 | 55,512 | 1.20 | |

| 17,931 | 0.50 | 28,809 | 0.75 | 26,601 | 0.67 | 30,975 | 0.67 | |

| 13,344 | 0.37 | 17,748 | 0.46 | 21,462 | 0.54 | 27,678 | 0.60 | |

| 18,051 | 0.50 | 20,520 | 0.53 | 22,416 | 0.56 | 26,856 | 0.58 | |

| 28,680 | 0.80 | 29,016 | 0.76 | 25,953 | 0.65 | 26,136 | 0.56 | |

| 11,460 | 0.32 | 14,547 | 0.38 | 16,353 | 0.41 | 19,860 | 0.43 | |

| 22,239 | 0.62 | 22,104 | 0.58 | 19,815 | 0.50 | 19,329 | 0.42 | |

| 8,379 | 0.23 | 10,761 | 0.28 | 12,942 | 0.32 | 16,605 | 0.36 | |

| 615 | 0.02 | 642 | 0.02 | 2,088 | 0.05 | 14,601 | 0.31 | |

| 6,168 | 0.17 | 7,257 | 0.19 | 9,582 | 0.24 | 14,349 | 0.31 | |

| 8,622 | 0.24 | 9,573 | 0.25 | 10,269 | 0.26 | 13,107 | 0.28 | |

| 7,773 | 0.22 | 8,994 | 0.23 | 9,576 | 0.24 | 11,928 | 0.26 | |

| 15,222 | 0.42 | 14,697 | 0.38 | 12,954 | 0.33 | 11,925 | 0.26 | |

| 11,301 | 0.31 | 7,686 | 0.20 | 7,059 | 0.18 | 10,992 | 0.24 | |

| 6,729 | 0.19 | 6,888 | 0.18 | 9,045 | 0.23 | 10,494 | 0.23 | |

| 12,486 | 0.35 | 10,764 | 0.28 | 8,988 | 0.23 | 10,440 | 0.22 | |

| 5,154 | 0.14 | 6,159 | 0.16 | 7,722 | 0.19 | 10,251 | 0.22 | |

| 3,948 | 0.11 | 4,875 | 0.13 | 6,153 | 0.15 | 9,291 | 0.20 | |

| 2,886 | 0.08 | 8,151 | 0.21 | 8,100 | 0.20 | 8,685 | 0.19 | |

| 5,787 | 0.16 | 6,756 | 0.18 | 6,711 | 0.17 | 7,776 | 0.17 | |

| 2,916 | 0.08 | 4,581 | 0.12 | 5,466 | 0.14 | 7,776 | 0.17 | |

| 657 | 0.02 | 1,764 | 0.05 | 3,588 | 0.09 | 7,719 | 0.17 | |

| 4,773 | 0.13 | 5,856 | 0.15 | 6,570 | 0.16 | 7,689 | 0.17 | |

| 1,617 | 0.05 | 2,472 | 0.06 | 3,759 | 0.09 | 7,539 | 0.16 | |

| 3,909 | 0.11 | 4,857 | 0.13 | 5,370 | 0.13 | 6,741 | 0.15 | |

| 3,792 | 0.11 | 4,614 | 0.12 | 4,914 | 0.12 | 6,627 | 0.14 | |

| 4,848 | 0.14 | 6,024 | 0.16 | 5,484 | 0.14 | 5,757 | 0.12 | |

| 1,320 | 0.04 | 2,211 | 0.06 | 2,850 | 0.07 | 5,691 | 0.12 | |

See also[]

- Pākehā settlers

- Demographics of New Zealand

- Europeans in Oceania

- Chinese immigration to New Zealand

References[]

- ^ Otago, University of. "History unearthed". Otago.ac.nz.

- ^ Germans: First Arrivals (from the Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand)

- ^ Glentanner. B. Lansley. Dornie Publishing. Invercargill 2013.

- ^ Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "4. – History of immigration – Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Teara.govt.nz.

- ^ "Archives New Zealand || Migration". Archives.govt.nz.

- ^ Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "6. – History of immigration – Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Teara.govt.nz.

- ^ "Pokeno Community Committee – Our Place". Pokenocommunity.nz.

- ^ "Waikato Immigration Scheme". Freepages.rootsweb.com.

- ^ Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "5. – History of immigration – Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Teara.govt.nz.

- ^ Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. "1881–1914: restrictions on Chinese and others". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- ^ Parker 2005, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Parker 2005, pp. 64–65.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "Review: Pacific Peoples in New Zealand". Hrc.co.nz. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 June 2008. Retrieved 8 June 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Immigration chronology: selected events 1840-2008". Parliament.nz. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ^ "Immigration regulation, Page 1". Teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ^ "Comprehensive immigration law closer". New Zealand Government. 5 December 2006. Retrieved 6 November 2007.

- ^ "New Zealand Visas | Immigration New Zealand". Immigration.govt.nz.

- ^ Home New Zealand Department of Labour – Migration Trends 2004/05 Archived 10 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 8 December 2007

- ^ "Documents confirm April consideration of language requirement change". New Zealand Government. 20 December 2002. Retrieved 6 November 2007.

- ^ Collins, Simon (24 April 2007). "Migrants firm's secret weapon". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ "Refugee quota lifting to 1500 by 2020". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ "Who can give New Zealand Immigration Advice?". Carmento. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ "Where to for Immigration?". New Zealand Government. 19 November 2005. Retrieved 6 November 2007.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Immigration Act passes third reading | Scoop News". Scoop.co.nz.

- ^ Levy, Danya. "Immigration changes give preference to wealthy". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ^ "Editorial – Immigration disquiet". Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ^ "Winston Peters delivers bottom-line binding referendum on abolishing Maori seats". Stuff.co.nz.

- ^ "Policy series: where do the parties stand on immigration?". NZ Herald – nzherald.co.nz. 22 August 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "National Population Estimates: At 30 June 2017". Statistics New Zealand. 14 August 2017.

- ^ "National Population Estimates: At 30 June 2014". Statistics New Zealand. 14 August 2017.

- ^ "International Travel and Migration: June 2017 – tables". Statistics New Zealand. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ "Afghanistan falls: NZ closes door on Afghan resettlement applications". Newstalk ZB. 26 August 2021. Archived from the original on 26 August 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ "Afghan interpreter says New Zealand has left his family to die at Taliban's hands". Radio New Zealand. 26 August 2021. Archived from the original on 26 August 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ The Great Public Works Policy of 1870, – Part III by N. S Woods, in New Zealand Railways Magazine, Volume 10, 1935. "The first appropriation which Vogel asked for in 1870 was £1,500,000 for immigration. He met with opposition [...]."

- ^ "Winston Peters' memorable quotes", The Age, 18 October 2005

- ^ Berry, Ruth (27 April 2005). "Peter's Asian warning". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ "Peters defends deputy's anti-Asian immigration comments", TV3, 3 April 2008

- ^ New Zealand Herald: "NZ First's Brown slammed for 'racist' anti-Asian remarks" 3 Apr 2008

- ^ "International travel and migration: December 2017". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ^ Stats NZ Infoshare - Table: Permanent & long-term migration by EVERY country of residence and citizenship (Annual-Dec)

- ^ "2013 Census QuickStats about culture and identity – tables". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ "2018 Census totals by topic – national highlights | Stats NZ". www.stats.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

Bibliography[]

- King, M, 2003, The Penguin History of New Zealand, Penguin, Auckland

- McMillan, K, 2006, "Immigration Policy", pp. 639–650 in New Zealand Government and Politics, ed. R. Miller, AUP

- History of Immigration at Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand

- News release from Caritas NZ

External links[]

- Immigration to New Zealand