Imperial German plans for the invasion of the United States

Imperial German plans for the invasion of the United States were ordered by staff officers from 1897 to 1903 as training exercises in planning for war. The hypothetical operations was supposed to force the US to bargain from a weak position and to sever its growing economic and political connections in the Pacific Ocean, the Caribbean, and South America so that German influence could increase there. Junior officers made various plans, but none were seriously considered and the project was dropped in 1906.

The first plan was made in the winter of 1897–1898, by Lieutenant , and targeted mainly American naval bases in Hampton Roads to reduce and constrain the US Navy and threaten Washington, D.C.

In March 1899, after significant gains made by the US in the Spanish–American War, the plan was altered to focus on a land invasion of New York City and Boston. In August 1901, Lieutenant Hubert von Rebeur-Paschwitz spied on the target areas and reported back.

A third plan was drawn up in November 1903 by naval staff officer Wilhelm Büchsel, called Operation Plan III (Operationsplan III), with minor adjustments made to the amphibious landing locations and the immediate tactical goals.

The Imperial German Navy, under Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, expanded greatly from 1898 to 1906 in order to challenge the British Royal Navy. It never was large enough to carry out any plans against the US, and there is no indication that they were ever seriously considered. The German Army, under Field Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen, assigned at least 100,000 troops in the invasion, was certain that the proposal would end in defeat. The plans were permanently shelved in 1906 and did not become fully public until 1970 when they were discovered in the German military archive in Freiburg[2] (an additional "rediscovery" occurred in 2002).[3]

The general staffs of all major powers make hypothetical war plans. The main objective is to estimate the amount of resources necessary to carry them out so that if the crisis ever emerged, precious time would not be wasted in developing them. Since all nations do it routinely, there is no sense that the plans developed by junior officers had any impact on national decision-making. Most of the plans never leave the War Department.[4]

Background[]

Germany was a latecomer in the Empire Race, which was already well underway when the country was unified in 1871. Germany, like other European powers, wanted the honor and prestige of having a colonial empire. German foreign policy in that period was intensely nationalistic; it changed from Realpolitik to the more aggressive Weltpolitik in an effort to expand the German Empire.[5][6]

Plan I[]

Germany's first plan was to attack naval power on the US East Coast and thus gain a free hand to establish a German naval base in the Caribbean, and to negotiate for another in the Pacific. Naval Lieutenant (later admiral and a naval historian) was assigned the task of drawing up the plans. Mantey, then 28 years old, began the work in late 1897, working through the winter into 1898. The secret plans were referred to as Mantey's "winter correspondence".[7] With support from the Kaiser, Tirpitz formed a plan to create a navy worthy of Germany's imperial ambitions, called the Tirpitz Plan. The Kaiser directed a series of naval expansions, collectively called the German Naval Laws, to bring his goal closer to fruition.[8] The Imperial German Navy had already started building powerful new battleships such as the Kaiser Friedrich III class which was to be completed by 1902.[9]

The first German invasion plan of the US called for a great German fleet to sail across the Atlantic Ocean and to engage and defeat the US Navy's Atlantic Fleet in a decisive battle. German naval artillery attacks would then be directed on the established Norfolk Naval Shipyard, the expanding Newport News Shipbuilding center, and all other naval strength in the Hampton Roads area of Virginia.[10] Von Mantey called this area the "most sensitive point" of American defenses, the reduction of which would force the US to negotiate.[11] Another attack was to be aimed at the prominent Portsmouth Naval Shipyard at the junction of the states of Maine and New Hampshire. The Harbor Defenses of New York, von Mantey thought, were too strong, with forts holding powerful anti-ship guns, to be considered a prime target.[3] Once America's most important naval shipyards were reduced, the German naval task forces were to remain in commanding blockade positions while a German negotiating team met with American government officials to wring from them whatever demands were determined appropriate by the Kaiser.[12]

The Kaiser found funding to be difficult for the expensive ships he wished for, and plans were delayed or shelved for the long-range armored cruisers necessary for supporting the fleet in a major engagement.[9] Meanwhile, the Spanish–American War broke out in 1898, with successful US action in both the Caribbean and the Pacific. By August, US ground and naval forces had gained control of Puerto Rico,[13] and a soon-to-be independent Cuba came under American economic influence. German plans for a Caribbean base were obstructed.[14]

Plan II[]

By March 1899, it was clear that the American occupation of the hoped-for Caribbean bases in Puerto Rico and Cuba was intended to be permanent. In response the Kaiser ordered the invasion plans redrawn by von Mantey.[3] Rather than the reduction of important shipyards, the new plan involved a two-pronged land invasion of New York City and Boston. Some 60 warships and a massive train of 40 to 60 cargo and troopships carrying 75,000 short tons (68,000 t) of coal, 100,000 soldiers and a large amount of army artillery would cross the Atlantic in 25 days. Following a decisive naval battle to obtain naval superiority, German troops were to be landed at Cape Cod and armed with artillery. The ground units were to advance upon Boston and fire into the city. The all-important attack on New York required high speed for success: it would begin with a troop landing on the peninsula of Sandy Hook, New Jersey, while warships worked to reduce the harbor fortifications, especially Fort Hamilton and Fort Tompkins. Next, the warships would advance to shell Manhattan and other areas of New York, hopefully causing American civilians to panic.[3]

In December 1900, the Kaiser decided that Plan II would best be carried out from a base on Cuba rather than sailing from Germany. This surprising development was alarming to his own General Staff as such a base would first need to be taken by force. Admiral Otto von Diederichs reported to the Kaiser that the German Navy was now stronger than the US Navy, so it was up to the army to solve the problem of the land strategy. General Alfred von Schlieffen was doubtful of the whole venture; he reported to the Kaiser that 100,000 troops "would probably be enough" to take Boston, but that many more would be required to take New York, a city of three million.[3] Von Diederichs thought that von Schlieffen was being "very clever" with the Kaiser, offering a seemingly positive answer that was impossible to carry out, as there was not even enough German shipping to carry 100,000 troops and their equipment.[3]

Plan III[]

By this time German officers had published what W. T. Stead called in 1901 "various fantastic schemes" for invading the United States, but contemporary observers saw them as unrealistic.[15] In August 1901, von Tirpitz sent secret orders to Lieutenant Hubert von Rebeur-Paschwitz (later Vice Admiral), a naval attaché serving at the German embassy in Washington, D.C. Von Rebeur-Paschwitz left Washington to scout out the proposed landing location on Cape Cod, which he found to be unsuitable because it was not within sight of friendly naval artillery support. He recommended shifting the landing to the beach near the lighthouse at Manomet Point. This beach could be supported by German warships standing out from Cape Cod; it also included a nearby hill with a commanding view. The hill was to be taken as quickly as possible because it was seen as useful for army-directed artillery support of the initial stages of the intended troop advance northward toward Boston some 45 miles (72 km) away. Von Rebeur-Paschwitz was already familiar with an up-to-date American defensive report authored by Captain Charles J. Train in mid-1901 as part of Train's duties for the US Navy Board of Inspection and Survey. Train, later made Rear Admiral, had written that Provincetown, Massachusetts, at the northern tip of Cape Cod, was the most vulnerable enemy landing location near Boston, and Cape Ann, 40 miles (64 km) to the north of Boston, was the second-most vulnerable. Using Train's report as his foundation, Von Rebeur-Paschwitz reported back to Tirpitz his opinion that two attacking forces should be landed at these two points for a pincer approach to Boston, converging from Manomet Point and Rockport. After seeing von Rebeur-Paschwitz's report, von Schlieffen wrote in December 1901 that the inexperience of von Rebeur-Paschwitz in army operations cast serious doubts on his judgement regarding landing troop locations and major attack strategy. The existence of Train's seacoast defense report, said von Schlieffen, was a signal that the US was alarmed about possible enemy invasion in the Boston area. The Americans would likely be better prepared to fight off such an invasion in the near future.[3]

From 1902 to November 1903, naval staff officer reworked the plans for Tirpitz, making small changes in tactics. These plans, called Operationsplan III (Operation Plan III), took world politics into consideration, specifying military and political advantages to be obtained by placing a naval base in Culebra, Puerto Rico; a position that could be used to threaten the Panama Canal.[16] During this time, von Mantey wrote in his diary that the "East Coast is the heart of the United States and this is where she is most vulnerable. New York will panic at the prospect of bombardment. By hitting her here we can force America to negotiate."[17]

Büchsel carefully noted that a condition for success in the German invasion of America was the absence of a major conflict in Europe. Another condition was a poor state of American preparedness. Both of these conditions were eroding at the time of Büchsel's authorship of the third plan. The US had been aroused, filled with a new martial spirit after its victory over Spain in 1898.[10] America had immediately begun building battleships, and the balance of sea power was shifting away from the German advantage reported by von Diederichs. The British Royal Navy, the strongest navy in the world, was expanding further, and other countries were planning very heavy dreadnought-type battleships. This put extra pressure on the German Navy which never reached a position of parity in the Anglo-German naval arms race nor did it expand enough to satisfy the warship and troopship numbers specified by von Mantey and then by Büchsel in the various US invasion plans.

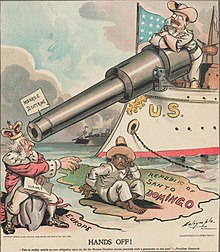

The Venezuela Crisis of 1902–1903 showed the world that the US was willing to use its naval strength to force an American viewpoint in world politics; the crisis established President Theodore Roosevelt's Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, setting a precedent for US intervention in South American–European affairs. In April 1904, the balance of power was seriously shifted in Europe with the signing of the Entente Cordiale by Britain and France. This improved diplomatic relationship between the two countries allowed French and British military forces to be shifted elsewhere, usually to the detriment of Wilhelm II's hope for a Kolonialreich—an empire of German influence much like the British Empire and the French colonial empire. Tsar Nicholas II of Russia refused to form a military alliance with Germany so the Kaiser determined that he should focus on strengthening Germany for a possible European conflict rather than an overseas invasion. The US invasion plans were shelved in 1906.[3]

Discovery[]

Hints of the German war plans were first found by scholar Alfred Vagts, who while doing research in the German Foreign Office on Wilhelmstrasse in Berlin during the 1930s, saw copies of reports from 1900 from Rebeur-Paschwitz to Tirpitz.[18] These discussed plans for attacking the large northeastern cities such as Boston and New York. Reference to this discovery was published by Vagts in a 1940 article in Political Science Quarterly.[19]

A discovery of a similar recommendation from 1900 by Diederichs for an attack upon New England, based upon a study done in March 1899, was found by German military historian Walther Hubatsch.[18] But in his 1958 book Der Admiralstab und die obersten Marinebehörden in Deutschland, 1848-1945, Hubatsch dismissed it as an example of routine thought exercise that exists in all naval planning staffs and not a mature plan.[20]

Next, historians John A. S. Grenville and George Berkeley Young found some plans.[21] These were copies of some German Admiralty archives found in the Public Record Office in London and described some of the 1899 and 1903 plans in general terms; discussion of them was included in the authors' 1966 book Politics, Strategy, and American Diplomacy: Studies in Foreign Policy, 1873–1917.[22]

The full plans were finally discovered in 1970 at the German military archives in Freiburg by Holger H. Herwig, a doctoral student at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, during his research into Wilhelm-era Germany.[2] The first publication of a study concerning the plans occurred later in 1970 in the German journal Militärgeschichtliche Mitteilungen in an article co-authored by Herwig and David F. Trask, a history professor at Stony Brook. The article was written in English but with quotations from documents left in German.[18] Knowledge of the plans achieved much wider dissemination with a front-page story on their discovery in the New York Times in April 1971, featuring a summary of the findings and an interview with Herwig.[2] Subsequently, the Herwig–Trask article was cited in dozens of books.[23] Description and analysis of the plans were also included as part of Herwig's 1976 book, Politics of Frustration: The United States in German Naval Planning, 1889–1941, this time with all material in English.[24]

Despite this background, Germany's Die Zeit newspaper announced a "discovery" of the formal invasion plans on 8 May 2002.[3] They too based this upon what they had found at the German military archives in Freiburg. Reporter Henning Seitz of Die Zeit wrote that the discovery "proves a continuity between the Kaiserreich and the Third Reich because the Nazis also wanted to risk a final fight for world domination with the United States forty years later."[11] The editorial staff of the American Heritage history magazine wrote a summary of the probable outcome of a notional Imperial German invasion of the US: they felt that the US under Roosevelt would not have accepted defeat or negotiated from a position of weakness. They compared the Kaiser's proposed invasion to the War of 1812 when serious political differences among Americans were set aside following the British burning of Washington in August 1814—an event which finally united the "United" States.[10]

See also[]

- Germany–United States relations

- Zimmermann Telegram, 1917 German plan for military alliance with Mexico against U.S.

- War Plan Black, U.S. war plans against Germany

- 1901 (novel), novel about a German invasion of U.S.

- 1920: America's Great War, novel about a German invasion of U.S.

- H. Irving Hancock#The_Invasion of the United States Series, juvenile novels about a German invasion of U.S.

- The War in the Air, H. G. Wells' novel depicting a German invasion of the U.S.

- The Fall of a Nation (novel) about Invasion of America by a German-led European Army

References[]

- ^ "US Ship Force Levels".

- ^ a b c Severo, Richard (24 April 1971). "A Footnote: Kaiser's Plan to Invade U.S." (PDF). The New York Times. pp. 1, 35.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sietz, Henning (8 May 2002). "In New York wird die größte Panik ausbrechen: Wie Kaiser Wilhelm II. die USA mit einem Militärschlag niederzwingen wollte". Zeit Online (in German). Die Zeit.

- ^ Max Boot (2006). War Made New: Technology, Warfare, and the Course of History, 1500 to Today. Gotham Books. p. 122. ISBN 9781592402229.

- ^ Fromkin, David (2004). Europe's Last Summer: Who started the Great War in 1914?, Vintage Books, pp. 17–20

- ^ Lyons, Michael J. (2000). World War I: A Short History, Prentice Hall, pp. 11–17.

- ^ Connolly, Kate (8 May 2002). "German archive reveals kaiser's plan to invade America". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited.

- ^ "Voices of the Great War: Kaiser Wilhelm II". The Great War and the Shaping of the 20th Century. PBS.org. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ a b Holger H. Herwig (1980). 'Luxury Fleet', The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. London: The Ashfield Press. p. 26. ISBN 0-948660-03-1.

- ^ a b c "The German Plan To Invade America –Newly Revealed: How Kaiser Wilhelm Planned to Keep America from Becoming a Global Power". American Heritage. 53 (6). November–December 2002.

- ^ a b Helm, Toby (9 May 2002). "How Kaiser Bill planned to invade United States". The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group Limited.

- ^ Kaufmann, J. E.; Kaufmann, H. W. (2007). Fortress America: The Forts That Defended America, 1600 to the Present. Da Capo Press. pp. 332–333. ISBN 978-0-306-81634-5.

- ^ Edgardo Pratts (2006), De Coamo a la Trinchera del Asomante (in Spanish) (First ed.), Puerto Rico: Fundación Educativa Idelfonso Pratts, ISBN 978-0976218562

- ^ Stone, Dean (2003). "Germans planned U.S. invasion century ago". Published in the Blount County Daily Times in Tennessee, January 12, 2003.

- ^ Stead, W. T. (1901). The Americanization of the World. Horace Markley. p. 372.

- ^ Strachan, Hew (2003). The First World War: Volume I: To Arms, Oxford

- ^ Jonathan Lewis, The First World War DVD, Disc One, Part Three: Global War, (Image Entertainment, 2005)

- ^ a b c Herwig, Holger H.; Trask, David F. (1970). "Naval Operations Plans between Germany and the United States of America 1898–1913: A Study of Strategic Planning in the Age of Imperialism". Militärgeschichtliche Mitteilungen (in English and German). 2: 5–32. See page 5 for discussion of the Vagts and Hubatsch discoveries.

- ^ Vagts, Alfred (March 1940). "Hopes and Fears of an American-German War, 1870–1915 II". Political Science Quarterly. 55 (1): 53–76. doi:10.2307/2143774. JSTOR 2143774. See p. 59 and fn. 62.

- ^ Hubatsch, Walther (1958). Der Admiralstab und die obersten Marinebehörden in Deutschland, 1848-1945. Frankfurt: Verlag für Wehrwesen Bernhard & Graefe. p. 92.

- ^ Spector, Ronald (1974). Admiral of the New Empire: The Life and Career of George Dewey. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. p. 147n.

- ^ Grenville, John A. S.; Young, George Berkeley (1966). Politics, Strategy, and American Diplomacy: Studies in Foreign Policy, 1873–1917. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 305–307.

- ^ See this Google Books search for example.

- ^ Herwig, Holger H. (1976). Politics of Frustration: The United States in German Naval Planning, 1889–1941. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. pp. 42–54, 57–66, 85–92.

- Imperial German Navy

- German Army (German Empire)

- Military plans

- Military history of Germany

- Cancelled invasions

- Cancelled military operations involving Germany

- Germany–United States military relations

- Invasions by Germany

- Invasions of the United States