International Amphitheatre

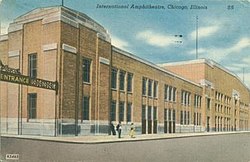

A postcard of the venue from 1953 | |

| |

| Address | 4220 South Halsted Street Chicago, Illinois 60609 United States |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°48′58″N 87°38′46″W / 41.81611°N 87.64611°WCoordinates: 41°48′58″N 87°38′46″W / 41.81611°N 87.64611°W[1] |

| Owner | Union Stock Yard and Transit Company (until 1983) |

| Capacity | 9,000 |

| Construction | |

| Opened | December 1, 1934[2] |

| Closed | 1999 |

| Demolished | August 3, 1999 (began) |

| Construction cost | $1.5 million ($29 million in 2020 dollars[3]) |

| Architect | Abraham Epstein[2][4] |

| Tenants | |

| Chicago American Gears (NBL/PBLA) (1944–1948) Chicago Packers (NBA) (1961–1962) Chicago Majors (ABL) (1961–1963) Chicago Bulls (NBA) (1966–1967) Chicago Cougars (WHA) (1972–1975) Chicago Sting (NASL) (1976) | |

The International Amphitheatre was an indoor arena located in Chicago, Illinois, that opened in 1934 and was demolished in 1999. It was located on the west side of Halsted Street, at 42nd Street, on the city's south side, in the Canaryville neighborhood, adjacent to the Union Stock Yards.

History[]

The arena was built for $1.5 million, by the Stock Yard company, principally to host the International Livestock Exhibition. The arena replaced Dexter Park, a horse-racing track that had stood on the site for over 50 years, prior to its destruction by fire on April 18, 1934.[2] The completion of the Amphitheatre ushered in an era where Chicago reigned as a convention capital. In an era before air conditioning and space for the press and broadcast media were commonplace, the International Amphitheatre was among the first arenas to be equipped with these innovations.

The arena, which seated 9,000, was the first home of the Chicago Packers of the NBA during 1961–62, before changing their name to the Chicago Zephyrs and moving to the Chicago Coliseum for their second season.[5] It was also the home of the Chicago Bulls during their inaugural season of 1966–67; they also played only one game in the Chicago Coliseum, a playoff game in their first season, as no other arena was available for a game versus the St. Louis Hawks. Afterwards, the Bulls then moved permanently to Chicago Stadium.

The Amphitheatre was also the primary home of the Chicago Cougars of the WHA from 1972 to 1975. It was originally intended to be only a temporary home for the Cougars, but the permanent solution, the Rosemont Horizon, was not completed until 1980, five years after the team folded and a year after the WHA ceased operation. The International Amphitheatre was the home for Chicago's wrestling scene for years as well as the Chicago Auto Show for approximately 20 years beginning in the 1940s.[6][7]

Strangely enough, on December 30, 1962 and January 5, 1964, the Chicago Amphitheatre hosted The Southside WinterNationals INDOOR Drag Races. With the smooth concrete floors, Drivers reported it was like racing on ICE. It was also reported that after the first races, cases of Coca Cola syrup were brought in, poured on the floor and allowed to dry overnight. Drivers like Arnie "The Farmer" Beswick, and Mr. Norm from Grand Spaulding Dodge later admitted the syrup did little to help traction. Staging was outside in the Chicago - January cold. Drivers did as many as 5 "burnouts" just to heat the rear tires. The shutdown area involved a sharp turn and wall that claimed more than a few of the entries.

National conventions[]

The Amphitheatre hosted several national American political conventions:

- 1952 Republican National Convention (nominated Dwight D. Eisenhower for President and Richard M. Nixon for Vice President; ticket won)

- 1952 Democratic National Convention (nominated Adlai E. Stevenson for President and John J. Sparkman for Vice President; ticket lost)

- 1956 Democratic National Convention (nominated Adlai E. Stevenson for President and Estes Kefauver for Vice President; ticket lost)

- 1960 Republican National Convention (nominated Richard M. Nixon for President and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. for Vice President; ticket lost)

- 1968 Democratic National Convention (nominated Hubert H. Humphrey for President and Edmund S. Muskie for Vice President; ticket lost)

The 1952 Republican National Convention had the distinction of being the first political convention broadcast live by television coast to coast, with special studio facilities provided for all the major networks.[8]

The 1968 Democratic National Convention was one of the most tumultuous political conventions in American history, noted by anti-war protests.

Notable performances[]

Prior to that, the Amphitheatre was noted for being the site of one of Elvis Presley's most notable concerts, in 1957, with the singer wearing his now legendary gold lame suit for the first time.[9]

On September 5, 1964 and August 12, 1966, The Beatles performed at the Amphitheatre. The 1966 show was the first show of what proved to be their last tour.[10]

The Stock Yards closed in 1971, but the Amphitheatre remained open, hosting rock concerts, college basketball and IHSA playoff games, circuses, religious gatherings, and other events. The shift of many conventions and trade shows to the more modern and more conveniently-located lakefront McCormick Place convention center, during the 1960s and 1970s, began the International Amphitheatre's decline; as other convention and concert venues opened in the suburbs, its bookings dropped more.

On March 13–14, 1976, the Midwest Regional of the North American Soccer League's 1976 Indoor tournament was hosted by the Chicago Sting at the Amphitheater. The Rochester Lancers won the Region to advance to the Final Four played in Florida.[11]

In October 1978, English rock group UFO recorded parts of what would become Strangers in the Night at the International Amphitheatre.

In December 1981, Joe Frazier had his final boxing match at the Amphitheatre against Floyd Cummings, which resulted in a draw.

Sale[]

Sold in 1983 for a mere $250,000, the sprawling Amphitheatre became difficult to maintain, and proved unable to attract enough large events to pay for its own upkeep. It was eventually sold to promoters Cardenas & Fernandez and then the City of Chicago, which had no more success at attracting events than its previous owner. In August 1999, demolition of the International Amphitheatre began.[7] An Aramark Uniform Services plant is located on the site once occupied by the Amphitheatre.

Gallery[]

The Amphitheatre was adjacent to the Union Stock Yards

1952 Republican National Convention

Adlai Stevenson during the 1952 Democratic National Convention

John F. Kennedy nominates Adlai Stevenson at the 1956 Democratic National Convention

Nixon supporters in Chicago during the 1960 Republican National Convention

Illinois delegates (including Richard M. Daley and Richard J. Daley) during the 1968 Democratic National Convention

References[]

- ^ "International Amphitheater (historical)". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. 15 January 1980.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Abbott, Noel (19 May 2016). "Throwback Thursday – International Amphitheatre". Epstein Global. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ 1634 to 1699: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy ofthe United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700-1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How much is that in real money?: a historical price index for use as a deflator of money values in the economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- ^ "International Amphitheater". Electronic Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society. 2005. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ Hareas, John. "A Colorful Tradition". Washington Wizards. Retrieved 2008-03-19.

- ^ Tito, Rich (April 21, 2004). "Regional Territories-WWA Indianapolis". Kayfabe Memories. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Boylan, Anthony Burke (May 30, 1999). "Amphitheatre Gets Its Final Curtain Call". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ^ "TV Goes to the Conventions". Popular Mechanics: 94–97. June 1952.

- ^ Cora, Casey (January 8, 2015). "Elvis in Chicago Was 'Electrifying': An 80th Birthday Celebration". DNAinfo.com. Archived from the original on March 16, 2016.

- ^ "Live: International Amphitheatre, Chicago". The Beatles Bible. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ^ Milbert, Neil (March 13, 1976). "Opener for the Sting tonight". Chicago Tribune. p. 5, Section 2.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to International Amphitheatre. |

- International Amphitheatre article in the Encyclopedia of Chicago

- International Amphitheatre at WTTW

| showEvents and tenants |

|---|

- 1934 establishments in Illinois

- 1999 disestablishments in Illinois

- Basketball venues in Chicago

- Boxing venues in Chicago

- Buildings and structures completed in 1934

- Chicago American Gears

- Chicago Bulls venues

- Chicago Packers venues

- Chicago Sting sports facilities

- Defunct college basketball venues in the United States

- Defunct indoor arenas in Illinois

- Defunct indoor ice hockey venues in the United States

- Defunct indoor soccer venues in the United States

- Defunct sports venues in Illinois

- Demolished buildings and structures in Chicago

- Demolished music venues in the United States

- Demolished sports venues in Illinois

- Event venues established in 1934

- Former National Basketball Association venues

- National Basketball League (United States) venues

- North American Soccer League (1968–1984) indoor venues

- Sports venues demolished in 1999

- Sports venues in Chicago

- Taekwondo venues

- World Hockey Association venues