International Churches of Christ

| International Churches of Christ | |

|---|---|

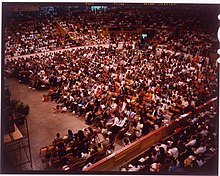

An International Church of Christ worship service | |

| Classification | non-denominational church |

| Associations | HOPE Worldwide,[1] IPI Books[2] |

| Region | Global (145 nations)[3][4] |

| Separations | International Christian Churches |

| Official website | International Churches of Christ |

The International Churches of Christ (ICOC) is a body of co-operating,[5] religiously conservative and racially integrated[4] Christian congregations. Beginning with 30 members, they grew to 37,000 members within the first 12 years. Currently they are numbered at over 128,000.[6] A formal break was made from the Churches of Christ in 1993 with the organization of the International Churches of Christ.[7]: 418 The ICOC believes that the whole Bible is the inspired Word of God.[8]

It is a family of churches spread across some 145 nations.[4] They consider themselves non-denominational.[4] They are structured with the intent to avoid two extremes: "overly centralised authority" on the one side and "disconnected autonomy" on the other side.[4][9] In 2000, it was described as "[a] fast-growing Christian organization known for aggressive proselytizing to [US] college students" and as "one of the most controversial religious groups on campus".[10] The largest congregation, the Los Angeles Church of Christ, has over 6000 members.[3] The largest church service was held in 2012 at the AT&T Center in San Antonio, Texas, during a World Discipleship Summit, with 17,800 in attendance.[11][12]

History[]

Origins in the Stone-Campbell Movement[]

The ICoC has its roots in a movement that reaches back to the period of the Second Great Awakening (1790–1870) of early nineteenth-century America. Barton W. Stone and Alexander Campbell are credited with what is today known as the Stone-Campbell or Restoration Movement. There are a number of branches of the Restoration movement and the ICoC was formed from within the Churches of Christ.[13] Specifically, it was born from a "discipling" movement that arose among the Churches of Christ during the 1970s.[7] This discipling movement developed in the campus ministry of Chuck Lucas.[7]

In 1967, Chuck Lucas was minister of the 14th Street Church of Christ in Gainesville, Florida (later renamed the Crossroads Church of Christ). That year he started a new project known as Campus Advance (based on principles borrowed from the Campus Crusade and the Shepherding Movement). Centered on the University of Florida, the program called for a strong evangelical outreach and an intimate religious atmosphere in the form of soul talks and prayer partners. Soul talks were held in student residences and involved prayer and sharing overseen by a leader who delegated authority over group members. Prayer partners referred to the practice of pairing a new Christian with an older guide for personal assistance and direction. Both procedures led to "in-depth involvement of each member in one another's lives".[14]

The ministry grew as younger members appreciated many of the new emphases on commitment and models for communal activity. This activity became identified by many with the forces of radical change in the larger American society that characterized the late sixties and seventies. The campus ministry in Gainesville thrived and sustained strong support from the elders of the local congregation in the 'Crossroads Church of Christ'. By 1971, as many as a hundred people a year were joining the church. Most notable was the development of a training program for potential campus ministers. By the mid-seventies, a number of young men and women had been trained to replicate the philosophy and methods of the Crossroads Church in other places.[15]

From Gainesville to Boston: 1970s–1980s[]

Among the early converts at Gainesville was a student named Kip McKean who had been personally mentored by Chuck Lucas. Thomas 'Kip' McKean, born in Indianapolis, Indiana,[16] completed a degree while training at Crossroads and afterward served as campus minister at several Churches of Christ locations. By 1979 his ministry grew from a few individuals to over three hundred making it the fastest growing Church of Christ campus ministry in America.[13] McKean then moved to Massachusetts, where he took over the leadership of the Lexington Church of Christ (soon to be called the Boston Church of Christ). Building on Lucas' initial strategies, McKean only agreed to lead the church in Lexington as long as every member agreed to be 'totally committed'. The church grew from 30 members to 3,000 in just over 10 years in what became known as the 'Boston Movement'.[13]

While still a Church of Christ congregation, they differentiated themselves through high levels of commitment, accountability, mentorship and a numerical focus on conversions. Meanwhile, the center of the new philosophy of ministry training and evangelism began to shift from Florida to Massachusetts. Moreover, the relationship between The Boston Church of Christ and larger CoC became more and more strained. During this period, Boston Movement leaders had begun to 'reconstruct' existing congregations. This began to cause a tension with the larger Church of Christ leadership that would eventually lead to a complete split. Parallel to this, the Boston Church of Christ began to plant new congregations at unprecedented speed for the Church of Christ at the time. The Boston congregation sent church plantings to Chicago and London in 1982, New York shortly thereafter, and Johannesburg in June 1986.[13][17]

In 1985 a Church of Christ minister and professor, Dr. Flavil Yeakley, administered the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator test to the Boston Church of Christ (BCC), the founding church of the ICOC. Yeakley passed out three MBTI tests, which asked members to perceive their past, current, and five-year in the future personality types.[18][19][20] While over 900 members were tested, 835 individuals completed all three forms. A majority of those respondents changed their perceived or imagined personality type scores on the three tests in convergence with a single type.[18][19] After completing the study, Yeakley observed that "The data in this study of the Boston Church of Christ does not prove that any certain individual has actually changed his or her personality in an unhealthy way. The data, however, does prove that there is a group dynamic operating in that congregation that influences its members to change their personalities to conform to the group norm".[21]

By the end of 1988 the churches in the Boston Movement were for all practical purposes a distinct fellowship, initiating a fifteen-year period during which there would be little contact between the CoC and the Boston Movement. By 1988, McKean was regarded as the leader of the movement.[17] It was at this time that the Boston church initiated its program of outreach to the poor called HopeWorldwide.[1] Also in 1988 McKean, finding that running the organization single-handedly had become unwieldy, selected a handful of men that he and Elena, his wife, had personally trained and named them World Sector Leaders.[22] In 1989 mission teams were officially sent out to Tokyo, Honolulu, Washington, DC, Manila, Miami, Seattle, Bangkok, and Los Angeles. That year, McKean and his family moved to Los Angeles to lead the new church planted some months earlier. Within a few years Los Angeles, not Boston, was the fulcrum of the movement.[17]

The ICoC: 1990s[]

In 1990 the Crossroads Church of Christ broke with the movement and, through a letter written to The Christian Chronicle, attempted to restore relations with the Churches of Christ.[7]: 419 By the early 1990s some first-generation leaders had become disillusioned by the movement and left.[7]: 419 The movement was first recognized as an independent religious group in 1992 when John Vaughn, a church growth specialist at Fuller Theological Seminary, listed them as a separate entity.[13] TIME magazine ran a full-page story on the movement in 1992 calling them "one of the world's fastest-growing and most innovative bands of Bible thumpers" that had grown into "a global empire of 103 congregations from California to Cairo with total Sunday attendance of 50,000".[23] A formal break was made from the Churches of Christ in 1993 when the group organized under the name "International Churches of Christ."[7]: 419 This new designation formalized a division that was already in existence between those involved with the Crossroads/Boston Movement and "original" Churches of Christ.[7]: 418 [24] Growth in the ICOC was not without criticism.[25] Other names that have been used for this movement include the "Crossroads movement," "Multiplying Ministries," and the "Discipling Movement".[14] Since each city had a single church, its membership might be large and geographically disperse; if so, it was divided into regions and then sectors of perhaps a few small suburban communities. This governing system attracted criticism as overly-authoritarian,[26] although the ICOC denied this charge. "It's not a dictatorship," said Al Baird, former ICOC spokesperson; "It's a theocracy, with God on top."[27]

Growth continued globally and in 1996 the independent organisation "Church Growth Today" named the Los Angeles ICoC as the fastest growing Church in North America for the second year running and another eight ICOC churches were in the top 100.[13] By 1999, the Los Angeles church reached a Sunday attendance of 14,000.[17] By 2001, the ICOC was an independent worldwide movement that had grown from a small congregation to 125,000 members and had planted a church in nearly every country of the world in a period of twenty years.[13]

The ICoC: 2000s[]

Once the fastest-growing Christian movement in the United States, membership growth slowed during the later half of the 1990s.[28] In 2000, the ICOC announced the completion of its six-year initiative to establish a church in every country with a population over 100,000.[22][29] In spite of this, numerical growth continued to slow. Beginning in the late 1990s, problems arose as McKean's moral authority as the leader of the movement came into question.[13] Expectations for continued numerical growth and the pressure to sacrifice financially to support missionary efforts took its toll. Added to this was the loss of local leaders to new planting projects. In some areas, decreases in membership began to occur.[17] At the same time, realization was growing that the accumulated costs of McKean's leadership style and associated disadvantages were outweighing the benefits. In 2001, McKean's leadership sins were affecting his family, with all of his children disassociating themselves from the church, and he was asked by a group of long-standing elders in the ICoC to take a sabbatical from overall leadership of the ICoC. On 12 November 2001, McKean, who had led the International Churches of Christ, issued a statement that he was going to take a sabbatical from his role of leadership in the church:

During these days Elena and I have been coming to grips with the need to address some serious shortcomings in our marriage and family. After much counsel with the Gempels and Bairds and other World Sector Leaders as well as hours of prayer, we have decided it is God's will for us to take a sabbatical and to delegate, for a time, our day-to-day ministry responsibilities so that we can focus on our marriage and family.

Nearly a year later, in November 2002 he resigned from the office and personally apologized citing arrogance, anger and an over-focus on numerical goals as the source of his decision.[13] Referring to this event, McKean said:

This, along with my leadership sins of arrogance, and not protecting the weak caused uncertainty in my leadership.[30]

The period following McKean's departure included a number of changes in the ICoC. Some changes were initiated from the leaders themselves and others brought through members.[31] Most notable was Henry Kriete, a leader in the London ICoC, who circulated an open letter detailing his feelings about theological exclusivism and authority in the ICoC. This letter affected the ICoC for the decade after McKean's resignation.[31]

Critics of the ICOC claim that Kip McKean's resignation sparked numerous problems.[32] However, others have noted that since McKean's resignation the ICOC has made numerous changes. The Christian Chronicle, a newspaper for the Churches of Christ, reports that the ICOC has changed its leadership and discipling structure.[33][34] According to the paper, "the ICOC has attempted to address the following concerns: a top down hierarchy, discipling techniques, and sectarianism".[35] In the years following McKean's resignation, the central leadership was replaced with "the co-operation agreement" with over 90% of the churches affirming to this new system of global co-ordination.[36]

Over time, McKean attempted to re-assert his leadership over the ICOC, yet was rebuffed. The Elders, Evangelists and Teachers wrote a letter to McKean expressing concern that there had been "no repentance" from his publicly acknowledged leadership sins.[37] McKean then began to criticize some of the changes that were being made.[38] After attempting to divide the ICOC he was disfellowshipped in 2006[38][39] and founded a church that he called the International Christian Church.[38]

The ICOC: 2020 plans[]

In 2010 the Evangelists Service Team formulated a "2020 vision plan", that all the regional families of churches have a plan to evangelize their geographic area of the world. The plan encompasses the need to strengthen existing small churches and plant new churches.[40]

They plan to build and strengthen those churches through a "best-practices" approach to ministry: oversee and support those churches through strong regional relationships and provide additional training for their ministers and congregations through the newly formed "Ministry Training Academy" being rolled out across the world, and provide global co-ordination and co-operation through "Service Teams" that specialize in "Campus Ministry", "Youth & Family Ministry" and other specialized ministries.[41]

Church governance[]

The International churches of Christ are a family of over 700 churches in 155 nations around the world. The 700 churches form 32 Regional Families of churches that oversee mission work in their respective geographic areas of influence. Each regional family of churches sends Evangelists, Elders and Teachers to an annual leadership conference, where delegates meet to pray, plan and co-operate world evangelism.[42][43] Mike Taliaferro, from San Antonio Texas, says "The co-operation plan is a far better way of co-ordinating and unifying a church family of the size and global nature of the ICOC. No longer can one man make sweeping decisions that affect all the churches, considering that many of those churches he may never have visited. Building unity and consensus through prayer and discussion takes time but is worth it. The spiritual fruit of the Delegates Conference in Budapest is testimony to the success of this much less authoritarian approach to that which we had in the past."[44] "Service Teams" provide global leadership and oversight. The Service Teams consists of an Elders, Evangelists, Teachers, Youth & Family, Campus, Singles, Communications & Administration, and HOPEww & Benevolence teams.[42]

One church[]

The ICOC holds that the Bible teaches the existence of a single universal church. One implication of this doctrine is that, while Christians may separate themselves into different, disunified churches (as opposed to just geographically separated congregations), it is not actually biblically right to do so. While no one claims to know who exactly is part of "the universal church" and who is not, the ICOC believes that anyone who follows the plan of salvation as laid out in the scriptures is added by God to his "One Universal Church".[45]

This is consistent with their historical roots in the Churches of Christ, which believe that Christ established only one church, and that the use of denominational creeds serves to foster division among Christians.[46]: 23, 24 [47][48] This belief dates to the beginning of the Restoration Movement; Thomas Campbell expressed an ideal of unity in his Declaration and address: "The church of Jesus Christ on earth is essentially, intentionally, and constitutionally one."[49]: 688

Ministry Training Academy[]

The current education and ministerial training program in the ICOC is the Ministry Training Academy (MTA). The MTA consists of twelve core courses that are divided into three areas of study: biblical knowledge, spiritual development, and ministry leadership. Each course requires at least 12 hours of classroom study in addition to course work. An MTA student who completes the twelve core classes receives a certificate of completion.[50]

HOPE worldwide[]

The ICOC directly administers or partners with over a dozen organizations. Some function as appendages of the church; others are entirely unrelated in their mission and activities. Of these, the largest and most well-known is HOPE worldwide,[1] a charitable foundation started as the benevolent arm of the ICOC, which serves as the primary beneficiary of the church's charitable donations for the poor.[1] Begun in 1991 with three projects in three countries and a budget of $600,000, as of 2012, HOPEww has grown to operate in 80 countries, serving 2,500,000 needy people each year, with an annual budget of $40,000,000.[51]

- In Africa, their projects serve 148,000 orphans in eight countries.

- In North America, there are 120 chapters of HOPEww, which mobilized 1300 volunteers to serve victims of Hurricane Sandy.

- In Central America, 53,000 pediatric exams and 58,000 adult medical exams have been conducted with 23,000 prescriptions written.

- In Cambodia, HOPEww runs and staffs two free hospitals.[51][52]

- In Bolivia, Hospital Arco Iris provides $1.4 million in free medical care.[53]

According to Charity Navigator, America's largest independent charity evaluator,[54] they have assigned HOPE Worldwide:

- An "Accountability & Transparency" rating of 100 out of 100.

- A "Financial" rating of 88.1 out of 100.

- An "Overall" rating of 4 out of 4 stars, with the Overall score of 91.55 out of 100.[55]

ICOC and mainstream Churches of Christ relations[]

With the resignation of McKean, some efforts are being made at reconciliation between the International Churches of Christ and the mainstream Churches of Christ. In March 2004, Abilene Christian University held the "Faithful Conversations" dialog between members of the Churches of Christ and International Churches of Christ. Those involved were able to apologize and initiate an environment conducive to building bridges. A few leaders of the Churches of Christ apologized for use of the word "cult" in reference to the International Churches of Christ. The International Churches of Christ leaders apologized for alienating the Churches of Christ and implying they were not Christians. Despite improvements in relations, there are still fundamental differences within the fellowship. Early 2005 saw a second set of dialogues with greater promise for both sides helping one another. Harding University is contemplating a distance learning program geared toward those ministers who were trained in the International Churches of Christ.[56] A video chronicling the "First forty years of the ICOC" details these developments.[57]

Church beliefs and practices[]

Beliefs[]

The ICOC regards the Bible to be the inspired Word of God. Through holding that their doctrine is based on the Bible alone, and not on creeds and traditions, they claim the distinction of being "non-denominational". Members of the International Churches of Christ generally emphasize their intent to simply be part of the original church established by Jesus Christ in his death, burial, and resurrection, which became evident on the Day of Pentecost as described in Acts 2. They believe that anyone who follows the plan of salvation as laid out in the scriptures is saved by the grace of God. They are a family of churches spread across 155 nations of the World. They are racially integrated congregations made up of a diversity of people from various age groups, economic, and social backgrounds. They believe Jesus came to break down the dividing wall of hostility between the races and people groups of this world and unite mankind under the Lordship of Christ (Ephesians 2:11-22).[8][58][59]

Like the Churches of Christ, the ICOC recognizes the Bible as the sole source of authority for the church and believes that the current denominational divisions are inconsistent with Christ's intent. Christians ought to be united.[60] The ICOC like the Christian Church, in contrast to the CoC, consider permissible practices that the New Testament does not expressly forbid.[61]

Pepperdine University, affiliated with Churches of Christ, published a document in 2010 highlighting the core beliefs of the ICOC that are shared with its counterpart:

GOD: FATHER, SON, AND HOLY SPIRIT

- 1. The eternal purpose of any Christian is to know God and to glorify him as God, and let our life shine so others will see God. Our devotion and ultimate loyalties are to the Father, who is over all and in all and through all; to Jesus the Son, who has been declared both Lord and Christ; and to the Holy Spirit, who lives in us and empowers us to overcome the workings of the sinful nature (Acts 2.22–36, Rom 8.12–28).

- 2. The cornerstone of our faith is our belief in Jesus Christ. Everything we hold dear in our faith originates from his words and his way of life (John 3.16, John 12.47–48, I John 2.5–6).

- 3. The Bible is the inspired and infallible Word of God. It is sharp, powerful, effective, challenging, exposing, and encouraging when it is revered, studied, preached, taught, and obeyed because it is from our Creator and therefore relevant for all generations (1 Tim 4.13, 2 Tim 3.16–17,4.1–5, Heb 4.12–13).

GOSPEL: THE WORK OF GOD

- 4. Our salvation totally depends on the work of God, prompted by his own mercy and grace, not our good deeds. That work redeems those who hear, believe and obey the Gospel message through baptism into Christ through their faith in God's power and continue to remain faithful unto death (Rom 2.7, Acts 2.22–37, Eph 2.8–10, Col 2.12, Heb 10.32–39, Jas 1.12).

- 5. Our earthly mission involves every member's participation in the Great Commission to "Seek and save what was lost," in bringing the good news of Jesus Christ to all parts of the world. As we go about this mission, our testimony must be consistent with a Christ-like life of doing good deeds and supporting and encouraging other Christians and churches around the world. In imitation of Jesus' mission, we are committed to remembering the poor by demonstrating compassion to those who suffer by regularly doing whatever we can to lessen their burdens and supporting group benevolent efforts through international agencies such as HOPE worldwide and others (Matt 28.19–20, Acts 10.37–38, Col 3.1–6, Luke 19.10, Gal 2.10, Jas 1.27).

- 6. Our motivation to love God, love each other and love the lost is prompted by God's love for us, demonstrated in its greatest form by the sacrificial death of Jesus Christ on a cross for our behalf (2 Cor 5.14–21,1 John 3.16, Luke 10.27).[62]

The ICOC teaches that "Christians are saved by the grace of God, through faith in Christ, at baptism."[4] Scriptures used to support this view include Ephesians 2:10, Romans 3:22, Acts 2:38 and Matthew 28:18–20.[4] They claim that "faith alone" is not sufficient, supported by James 2:14–26, unless an individual by faith obeys God in baptism, believing that baptism is necessary for the forgiveness of sins. The ICOC maintains that anyone, anywhere, who follows God's plan of salvation as found in the scriptures is saved.[4]

The ICOC teaches on the basis of James 2:20–26 that the "Sinner's Prayer" is not biblical.[4] Steven Francis Staten argues that the sinner's prayer represents "a belief system and a salvation practice that no one had ever held until relatively recently."[63] The evangelical preacher Francis Chan has made statements that contradict the sinner's prayer and emphasizes baptism and the Holy Spirit.[64] David Platt, head pastor of The Church at Brook Hills and author of the book Radical in an article in Christianity Today: "Is it possible for people to say they believe in Jesus, to say they have accepted Jesus, to say that they have received Jesus, but they are not saved and will not enter the kingdom of heaven? Is it possible? Absolutely, it's possible. It's not just possible; it is probable". While he affirmed that people calling out to God with repentant faith is fundamental to being saved, he said his comments about the "sinner's prayer" have been deeply motivated "by a concern for authentic conversions".[65]

In agreement with the prevailing view in the Churches of Christ, the ICoC believes that it is necessary to have an understanding of Baptism's role in salvation.[66]

Practices[]

Sunday worship[]

A typical Sunday morning service involves singing, praying, preaching, and the sacrament of the Lord's Supper. An unusual element in ICOC tradition is the lack of established church buildings. Congregations meet in rented spaces: hotel conference rooms, schools, public auditoriums, conference centers, small stadiums, or rented halls, depending on the number of parishioners. Though the church is not static, neither is it "ad hoc" — the leased locale is converted into a Worship Facility. "From an organizational standpoint, it's a great idea", observes Boston University Chaplain Bob Thornburg. "They put very little money into buildings...You put your money into people who reach out to more people in order to help them become Christians."[67]

This practice of not owning buildings changed when the Tokyo Church of Christ became the first ICOC church to build its own church building. This building was designed by the Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki.[68] This became an example for other ICOC churches to follow suit.

One Year Challenge[]

To provide an international service opportunity for college-age students, the ICOC has a program called the "One Year Challenge" (OYC), where graduating students take a year off and go and serve another church in the Third World[69] or a recently planted church in the First World looking to reach younger people with the gospel.[70] The One Year Challenge program currently operates in ten countries, including: China, Taiwan, The Czech Republic, Hungary, Haiti, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, The U.K. and The U.S.[71]

Bible talks[]

A Bible Talk is a small group of disciples that meet usually once a week. They can meet almost anywhere, including college dormitories, restaurants, and members' houses. Bible Talks, or 'Family Groups', are designed so that disciples can read the Bible together and build relationships with others in the church. All are encouraged to invite guests as a way for the guest to be introduced to the Church in a more informal setting. The Bible Talk is very similar to the "cell group" or "small group" structure found in many churches to facilitate close relationships amongst members.

Discipling[]

Disciples are student-followers of Jesus Christ. The practice of discipling involves mentoring and accountability partnerships and is one of the central elements of the ICOC's beliefs. Members who have mentoring and accountability relationships ("discipling") believe that this practice is based upon and encouraged by Biblical passages like: Ecclesiastes 4:9-12; Proverbs 11:25; Proverbs 27:17; Hebrews 10:25; James 5:16 among others. They also cite numerous examples of such relationships found in scripture like Moses and Joshua, Elijah and Elisha, Jesus and the early disciples, Paul and Timothy.

Kip McKean, who was the leader of the ICOC until 2001, said:

I believe it is biblical for us to imitate the relationship Jesus had with the apostles and the relationships they had with one another. For example, the apostles had a student/teacher or younger brother/older brother relationship with Jesus. They also had adult/adult relationships with each other. Jesus paired the apostles for the mission. (Matthew 10) Both types of relationships are essential to lead people to maturity. Another text that demonstrates the student/teacher relationship is in Titus 2 where the older women are to train the younger women.

– Kip McKean[27]

The church's emphasis on discipling has not been without its critics. A number of ex-members have expressed problems with discipling in the ICOC.[21] After the removal of McKean, the practice of "Discipleship Partners" has taken on a more "servant leadership approach". Michael Taliaferro explains in a survey of ICOC churches: "We fully recognize that discipleship partners today are (thankfully) much different than what many were experiencing 10 years ago. We know that we blew it in this area in the past. We also feel that we have grown. As far as we know, no churches assign the partners (everyone chooses for themselves), and all respondents were very convicted about the need for relationships that are not harsh or bossy, but rather Biblically balanced, respectful, and mature."[72]

US college campuses[]

The ICOC has a history of over thirty years of evangelizing on college campuses.[41] Each year an International Campus Ministry Conference (ICMC) is held for college students. In 2004, the ICMC in San Antonio there were 200 campus participants. In 2011, they had 2500 students meet in Denver, Colorado and Athens, Georgia[73] In 2013, the Campus Ministries of the ICOC raised $12,900 for "Chance for Africa", a charity that helps educate Primary and Secondary School children in Africa.[74] The 2013 ICMC conferences were held in Orlando, Florida and San Diego with 2700 students in attendance. The students set a new World Record by holding a lightsaber battle with 1200 lightsabers being used, (bettering the old record by 200). These lightsabers were then donated to orphans.[75]

The ICOC has received criticism for its proselytizing on US college campuses. U.S. News and World Report ran an article in 2000 discussing proselytizing on college campuses. The article's author, Carolyn Kleiner, describes the ICOC as "[a] fast-growing Christian organization known for aggressive proselytizing to college students" and as "one of the most controversial religious groups on campus". Professor Jeffrey K. Hadden, responded "[e]very new religion experiences a high level of tension with society because its beliefs and ways are unfamiliar. But most, if they survive, we come to accept as part of the religious landscape".[76]

At the University of Southern California, the school newspaper ran an article criticizing the church, after questioning the sources of the article the Dean of Religious Life, Revd. Elizabeth Davenport, Senior Associate Dean of Religious Life, and Sherry Caudle, Administrator for the Office of Religious Life wrote a letter to the editor. The school officials said that the author's information was "outdated and misleading." They said "the church is unfairly and incorrectly identified" as a problem group. They also said that the truth is "the church has been a very positive influence in the lives of the USC students in recent years."[77]

Singapore court case[]

The Central Christian Church in Singapore, which is a part of the ICOC family of churches, won a court case (SINGAPORE HIGH COURT – SUIT NOs 846 and 848 of 1992 Judges LAI KEW CHAI J Date 29 August 1994 Citation [1995] 1 SLR 115) where the judge ruled against a newspaper that had accused the Church of being a cult. An expert on religious studies testified that the Central Christian Church's practices were "neither strange, unnatural or harmful."[78]

Affiliated organizations[]

Multiple ICOC churches have a Chemical Recovery Ministry aimed at helping people with addictions to alcohol, drugs and nicotine.[79]

The Chemical Recovery ministry started in New York with the help of Mike and Brenda Leatherwood and Steve and Lisa Johnson. As a result of many struggling due to chemical dependency, an organization was created to help members suffering from addiction, recapture their relationship with Christ through a guided course, using a book called, "Some Sat in Darkness'". Today the CR ministry continues to flourish especially in larger cities like Seattle, where a thriving group led by Paul Martin (a Deacon of the Seattle Church of Christ Family) holds a monthly open house.[80]

The following institutions are operated or managed by the ICOC:

- KNN a production of Kingdom News Network (KNN) — non-profit religious corporation in Illinois.

- Disciples Today - The official communications and news hub of the ICOC

- ICOC Leaders - Leadership news and events

- Keydogo - Video Production Company

- Illumination Publishers International (IPI) — Christian writing and audio teaching[81]

- Athens Institute of Ministry[82]

- Baltic Nordic Missions Alliance

- European Bible School

- Florida Missions Council

- International Missions Society, Inc. (IMS)

- Taiwan Mission Adventure

- Ministry Training Academy

- Strength in Weakness

- Pure and Simple Ministry

See also[]

- Churches of Christ

- History of Christianity

- Restorationism

- Second Great Awakening

- Non-denominational Christianity

- John Oakes (apologist)

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "HOPE worldwide". hopeww.org.

- ^ "IP > Featured Items". ipibooks.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "ICOC Info". dtodayinfo.net.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i "About The ICOC," ICOC HotNews, 3 February 2013 (accessed 17 November 2013)

- ^ ICOC Cooperation Service Team Chairmen (28 August 2009). "Plan for United Cooperation Summary". icocco-op.org. International Churches of Christ Co-operation Churches. Archived from the original on 25 September 2013. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ "ICOC Churches". International Churches of Christ Leadership. 15 April 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on International Churches of Christ

- ^ Jump up to: a b "About The ICOC - ICOC HotNews". www.icochotnews.com.

- ^ Justin Renton, "Autonomy? No way! Glorious co-operation between the ICOC churches," ICOC HotNews, 9 August 2010 (accessed 16 November 2013)

- ^ "1500 Campus Students from the International Churches of Christ Help Rebuild New Orleans". icochotnews.com.

- ^ "San Antonio Summit Simply Amazing!". icochotnews.com.

- ^ Roger Lamb. "2012 WDS - A Defining Moment for the International Churches of Christ". disciplestoday.org.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Stanback, C. Foster. Into All Nations: A History of the International Churches of Christ. IPI, 2005

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Paden, Russell (July 1995). "The Boston Church of Christ". In Miller, Timothy (ed.). America's Alternative Religions. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 133–36. ISBN 978-0-7914-2397-4. Retrieved 7 August 2007.

- ^ Wilson, John F. "The International Church of Christ: A Historical Overview." Leaven (Pepperdine University), 2010: 1–5.

- ^ "Kipmckean.com - Get Your Answers Here!". Kip McKean.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Wilson, John F. "The International Church of Christ: A Historical Overview." Leaven (Pepperdine University), 2010: 1–5

- ^ Jump up to: a b (1993). "1". Recovery from Cults. New York: W. W. Norton and Company. p. 39.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gasde, Irene; Richard A. Block (1998). "Cult Experience: Psychological Abuse, Distress, Personality Characteristics, and Changes in Personal Relationships". Cultic Studies Journal. 15 (2): 58.

- ^ Yeakley, Flavil (1988). The Discipling Dilemma. Gospel Advocate Company. ISBN 0892253118.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Giambalvo, Carol (1997). The Boston Movement: Critical Perspectives on the International Churches of Christ. American Family Foundation. p. 219. ISBN 0931337062.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Brief History of the ICOC". KipMcKean.com. 6 May 2007. Archived from the original on 20 June 2007. Retrieved 9 July 2007.

- ^ Ostling, Richard N. "Keepers of the Flock." Time Magazine, 18 May 1992.

- ^ Leroy Garrett, The Stone-Campbell Movement: The Story of the American Restoration Movement, College Press, 2002, ISBN 0-89900-909-3, ISBN 978-0-89900-909-4, 573 pages

- ^ "IcocHotNews Poll: Do We Still Have Discipleship Partners? Surprising Results". icochotnews.com.

- ^ Davis, Blair J. (March 1999). "The Love Bombers". Philadelphia City Paper. Archived from the original on 4 April 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ostling, Richard N. (18 May 1992). "Keepers of the Flock". Time. Archived from the original on 14 December 2006. Retrieved 12 July 2007.

- ^ Mike Taliaferro, "Has a New Era Begun for the ICOC?" Disciples Today, 30 January 2013

- ^ McKean, Kip (4 February 1994). "Evangelization Proclamation" (PDF). International Churches of Christ. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2007. Retrieved 9 July 2007.

- ^ McKean, Kip (21 August 2005). "The Portland Story". Portland International Church of Christ. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 9 July 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stanback, F: Into All Nations, IPI, 2005

- ^ Callahan, Timothy (1 March 2003). "Boston movement' founder quits". Christianity Today. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ "Revisiting the Boston Movement: ICOC growing again after crisis". christianchronicle.org.

- ^ "Revisiting the Boston Movement – ICOC Growing Again After Crisis". Christian Chronicle.

- ^ "Church Growth: The Cost of Discipleship?-Despite allegations of abuse of authority, the International Churches of Christ expands rapidly". Christianity Today.

- ^ "List of Co-Operation Churches". Disciples Today.

- ^ Brothers the ICOC. "Brothers' Letter to Kip McKean". disciplestoday.org.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Carrillo, Robert (2009), "The International Churches of Christ (ICOC)," Leaven Archived 2 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Vol. 17, Issue 3, Article 11, Pepperdine University (accessed 28 November 2013)

- ^ Brothers the ICOC. "Brothers' Statement to Kip McKean". disciplestoday.org.

- ^ "International Churches of Christ (ICOC) Co-operation Churches - Home". disciplestoday.org. Archived from the original on 18 April 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "International Churches of Christ 2020 vision plans". icochotnews.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Roger Lamb. "International Churches of Christ (ICOC) Co-operation Churches - ICOC Service Teams". icocco-op.org. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ "International Churches of Christ (ICOC) Co-operation Churches". icocco-op.org. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013.

- ^ Budapest Editorial. YouTube. 28 May 2012.

- ^ Beliefs, Columbia Church of Christ website (accessed 24 December 2013)

- ^ V. E. Howard, What Is the Church of Christ? 4th Edition (Revised) Central Printers & Publishers, West Monroe, Louisiana, 1971

- ^ O. E. Shields, "The Church of Christ," Archived 29 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine The Word and Work, VOL. XXXIX, No. 9, September 1945.

- ^ J. C. McQuiddy, "The New Testament Church", Gospel Advocate (11 November 1920):1097–1098, as reprinted in Appendix II: Restoration Documents of I Just Want to Be a Christian, Rubel Shelly (1984)

- ^ Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, "Slogans", in The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8,

- ^ "ICOC Ministry Training Academy Guidelines". ICOC Ministry Training Academy. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "YOUR HOPE WORLDWIDE - NOVEMBER 10th". icochotnews.com.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 2013-10-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 2013-10-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Charity Navigator Rating - HOPE worldwide". Charity Navigator.

- ^ "Charity Navigator Rating - HOPE worldwide". Charity Navigator.

- ^ Robert Carrillo, "The Church of Christ and the International Churches of Christ," Archived 27 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine Restoration Press

- ^ Mattox, David (January 2012). "ICOC Church History Video: 40 Years". Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "What We Believe". ctcoc.co.za. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016.

- ^ "What We Believe". nwregion.co.za.

- ^ Kip McKean, "Interview with Kip McKean," Archived 21 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine The Christian Chronicle, January 2004

- ^ McAlister & Tucker (1975). Pages 242 – 247

- ^ (2010) "The International Churches of Christ Statement of Shared Beliefs," Leaven: Vol. 18: Iss. 2, Article 4.

- ^ . "The Sinner's Prayer". The Interactive Bible. Retrieved 12 March 2007.

- ^ Francis Chan - baptism. YouTube. 21 February 2011.

- ^ David Platt. "David Platt: What I Really Think About the 'Sinner's Prayer,' Conversion, Mission, and Deception - Christianity Today". ChristianityToday.com.

- ^ Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Baptism

- ^ David Frey (July 1999). "The Fear of God: Critics Call Thriving Nashville Church a Cult". InReview Online.

- ^ Tokyo Church of Christ page on the McGill University website (accessed 21 February 2011)

- ^ "Some people, taking the One Year Challenge in South Africa, tell their story". icochotnews.com.

- ^ disciplesadventures.org

- ^ "One Year Challenge". oneyearchallenge. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ "IcocHotNews Poll: Do We Still Have Discipleship Partners? Surprising Results". icochotnews.com.

- ^ Kevin Thompson. "East Coast ICMC Takes it DEEPER in Athens". disciplestoday.org.

- ^ Tony Martin - Boston, MA. "Benefit Concert Raises over $3,000 at ICMC East for Children in Africa - Disciples Today - ICOC". disciplestoday.org.

- ^ "2013 International Campus Ministry Conference Review". icochotnews.com.

- ^ "A Push Becomes A Shove Colleges get uneasy about proselytizing". US News and World Report. Archived from the original on 27 June 2008.

- ^ "USC Newspaper Apologizes for Article about ICOC". icochotnews.com.

- ^ "NewspaperSG". nl.sg. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013.

- ^ The Chemical Recovery Fellowship. "Misc - ChemicalRecovery.Org". chemicalrecovery.org. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2006.

- ^ Fellowship, The Chemical Recovery. "Recovery Stories". www.chemicalrecovery.org.

- ^ "IP > Featured Items". ipibooks.com. Archived from the original on 11 August 2007.

- ^ icocinfo.org affiliated Organizations Archived 6 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to International Churches of Christ. |

- Official website

- News and opinion on the ICOC

- International Churches of Christ in LinkedIn (in English)

- International Churches of Christ on Facebook (in Portuguese)

- Igreja de Cristo Internacional de São Paulo (in Portuguese)

- International Churches of Christ (in English)

- Igreja de Cristo Internacional de Guaianases – Cifras de música e louvor (in Portuguese)

- Igreja de Cristo Internacional de Belo Horizonte – Jovens (in Portuguese)

- International Churches of Christ on Instagram (in Portuguese)

- Video on YouTube (in Portuguese)

- Churches of Christ

- Christian missions

- Religious organizations established in the 1980s

- Fundamentalist denominations

- Christian denominations established in the 20th century

- Christian new religious movements

- Evangelical denominations in North America

- Arminian denominations