International Cometary Explorer

Artist rendering of ICE | |||

| Names | International Sun-Earth Explorer-3 International Sun-Earth Explorer-C Explorer 59 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mission type | Magnetospheric research ISEE-3: Sun/Earth L1 orbiter ICE: 21P/G-Z & Halley fly-by | ||

| Operator | NASA[1] | ||

| COSPAR ID | 1978-079A | ||

| SATCAT no. | 11004 | ||

| Mission duration | Launch to last routine contact: 18 years, 8 months, 22 days Launch to last contact: 36 years, 1 month, 3 days | ||

| Spacecraft properties | |||

| Manufacturer | Fairchild Industries | ||

| Launch mass | 479 kg (1,056 lb) | ||

| Dry mass | 390 kg (860 lb) | ||

| Dimensions | 1.77 × 1.58 m (5.8 × 5.2 ft) | ||

| Power | 173 W | ||

| Start of mission | |||

| Launch date | August 12, 1978, 15:12 UTC | ||

| Rocket | Delta 2914 #144 | ||

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral SLC-17B | ||

| End of mission | |||

| Deactivated | Contact suspended: May 5, 1997 | ||

| Last contact | September 16, 2014 | ||

| Orbital parameters | |||

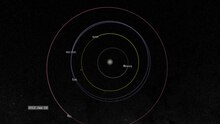

| Reference system | Heliocentric | ||

| Eccentricity | 0.05 | ||

| Perihelion altitude | 0.93 AU (139,000,000 km; 86,400,000 mi) | ||

| Aphelion altitude | 1.03 AU (154,000,000 km; 95,700,000 mi) | ||

| Inclination | 0.1° | ||

| Period | 355 days | ||

| Epoch | March 28, 1986 | ||

| |||

Explorers program | |||

The International Cometary Explorer (ICE) spacecraft (designed and launched as the International Sun-Earth Explorer-3 (ISEE-3) satellite), was launched August 12, 1978, into a heliocentric orbit. It was one of three spacecraft, along with the mother/daughter pair of ISEE-1 and ISEE-2, built for the International Sun-Earth Explorer (ISEE) program, a joint effort by NASA and ESRO/ESA to study the interaction between the Earth's magnetic field and the solar wind.

ISEE-3 was the first spacecraft to be placed in a halo orbit at the L1 Earth-Sun Lagrangian point.[2] Renamed ICE, it became the first spacecraft to visit a comet,[3] passing through the plasma tail of comet Giacobini-Zinner within about 7,800 km (4,800 mi) of the nucleus on September 11, 1985.[4]

NASA suspended routine contact with ISEE-3 in 1997, and made brief status checks in 1999 and 2008.[5][6]

On May 29, 2014, two-way communication with the spacecraft was reestablished by the ISEE-3 Reboot Project, an unofficial group[7] with support from the Skycorp company.[8][9][10] On July 2, 2014, they fired the thrusters for the first time since 1987. However, later firings of the thrusters failed, apparently due to a lack of nitrogen pressurant in the fuel tanks.[11][12] The project team initiated an alternative plan to use the spacecraft to "collect scientific data and send it back to Earth",[13] but on September 16, 2014, contact with the probe was lost.[14]

Original mission: International Sun/Earth Explorer 3 (ISEE-3)[]

ISEE-3 carries no cameras; instead, its instruments measure energetic particles, waves, plasmas, and fields.

ISEE-3 originally operated in a halo orbit about the L1 Sun-Earth Lagrangian point, 235 Earth radii above the surface (about 1.5 million km, or 924,000 miles). It was the first artificial object placed at a so-called "libration point",[15] entering orbit there on November 20, 1978,[2] proving that such a suspension between gravitational fields was possible. It rotates at 19.76 rpm about an axis perpendicular to the ecliptic, to keep it oriented for its experiments, to generate solar power and to communicate with Earth.

The purposes of the mission were:

- to investigate solar-terrestrial relationships at the outermost boundaries of the Earth's magnetosphere;

- to examine in detail the structure of the solar wind near the Earth and the shock wave that forms the interface between the solar wind and Earth's magnetosphere;

- to investigate motions of and mechanisms operating in the plasma sheets; and,

- to continue the investigation of cosmic rays and solar flare emissions in the interplanetary region near 1 AU.

Second mission: International Cometary Explorer[]

After completing its original mission, ISEE-3 was re-tasked to study the interaction between the solar wind and a cometary atmosphere. On June 10, 1982, the spacecraft performed a maneuver which removed it from its halo orbit around the L1 point and placed it in a transfer orbit. This involved a series of passages between Earth and the Sun-Earth L2 Lagrangian point, through the Earth's magnetotail.[16] Fifteen propulsive maneuvers and five lunar gravity assists resulted in the spacecraft being ejected from the Earth-Moon system and into a heliocentric orbit. Its last and closest pass over the Moon, on December 22, 1983, was only 119.4 km (74 mi) above the lunar surface; following this pass, the spacecraft was re-designated as the International Cometary Explorer (ICE).[17]

Giacobini-Zinner encounter[]

Its new orbit put it ahead of the Earth on a trajectory to intercept comet Giacobini-Zinner. On September 11, 1985, the craft passed through the comet's plasma tail.[17]

ICE did a flyby of the comet nucleus at a distance of 7,800 km (4,800 mi) of the nucleus on September 11, 1985.[18]

Halley encounter[]

ICE transited between the Sun and Comet Halley in late March 1986, when other spacecraft were near the comet on their early-March comet rendezvous missions. (This "Halley Armada" included Giotto, Vega 1 and 2, Suisei and Sakigake.) ICE flew through the tail; its minimum distance to the comet nucleus was 28 million kilometres (17,000,000 mi).[19] For comparison, Earth's minimum distance to Comet Halley in 1910 was 20.8 million kilometres (12,900,000 mi).[20]

Heliospheric mission[]

An update to the ICE mission was approved by NASA in 1991. It defines a heliospheric mission for ICE consisting of investigations of coronal mass ejections in coordination with ground-based observations, continued cosmic ray studies, and the Ulysses probe. By May 1995, ICE was being operated under a low duty cycle, with some data-analysis support from the Ulysses project.

End of mission[]

On May 5, 1997, NASA ended the ICE mission, leaving only a carrier signal operating. The ISEE-3/ICE downlink bit rate was nominally 2048 bits per second during the early part of the mission, and 1024 bit/s during the Giacobini-Zinner comet encounter. The bit rate then successively dropped to 512 bit/s (on December 9, 1985), 256 bit/s (on January 5, 1987), 128 bit/s (on January 24, 1989) and finally to 64 bit/s (on December 27, 1991). Though still in space, NASA donated the craft to the Smithsonian Museum.[21]

By January 1990, ICE was in a 355-day heliocentric orbit with an aphelion of 1.03 AU, a perihelion of 0.93 AU and an inclination of 0.1 degree.

Further contact[]

In 1999, NASA made brief contact with ICE to verify its carrier signal.

On September 18, 2008, NASA, with the help of KinetX, located ICE using the NASA Deep Space Network after discovering that it had not been powered off after the 1999 contact. A status check revealed that 12 of its 13 experiments were still functioning, and it still had enough propellant for 150 m/s (490 ft/s) of Δv.

It was determined to be possible to reactivate the spacecraft in 2014,[22] when it again made a close approach to Earth, and scientists discussed reusing the probe to observe more comets in 2017 or 2018.[23]

Reboot effort[]

Sometime after NASA's interest in the ICE waned, others realized that the spacecraft might be steered to pass close to another comet. A team of engineers, programmers, and scientists began to study the feasibility and challenges involved.[10]

In April 2014, its members formally announced their intentions to "recapture" the spacecraft for use, calling the effort the ISEE-3 Reboot Project. A team webpage said, "We intend to contact the ISEE-3 (International Sun-Earth Explorer) spacecraft, command it to fire its engine and enter an orbit near Earth, and then resume its original mission... If we are successful we intend to facilitate the sharing and interpretation of all of the new data ISEE-3 sends back via crowd sourcing."[24]

On May 15, the project reached its crowdfunding goal of US$125,000 on RocketHub, which was expected to cover the costs of writing the software to communicate with the probe, searching through the NASA archives for the information needed to control the spacecraft, and buying time on the dish antennas.[25] The project then set a "stretch goal" of $150,000, which it also met with a final total of $159,502 raised.[26]

The project members were working on deadline: if they got the spacecraft to change its orbit by late May or early June 2014, or in early July by using more fuel, it could use the Moon's gravity to get back into a useful halo orbit.[27][28][29]

Replacing lost hardware[]

Earlier in 2014, officials with the Goddard Space Flight Center said the Deep Space Network equipment necessary to transmit signals to the spacecraft had been decommissioned in 1999, and was too expensive to replace.[30] However, project members were able to find documentation for the original equipment and were able to simulate the complex modulator/demodulator electronics using modern software-defined radio (SDR) techniques and open-source programs from the GNU Radio project. They obtained the needed hardware, an off-the-shelf SDR transceiver[31] and power amplifier,[32] and installed it on the 305-meter Arecibo dish antenna on May 19, 2014.[32][33] Once they gained control of the spacecraft, the capture team planned to shift the primary ground station to the 21-meter dish located at Kentucky's Morehead State University Space Science Center.[32] The 20-meter dish antenna in Bochum Observatory, Germany, would be a support station.[32]

Although NASA was not funding the project, it made advisors available and gave approval to try to establish contact. On May 21, 2014, NASA announced that it had signed a Non-Reimbursable Space Act Agreement with the ISEE-3 Reboot Project. "This is the first time NASA has worked such an agreement for use of a spacecraft the agency is no longer using or ever planned to use again," officials said.[34]

Contact reestablished[]

On May 29, 2014, the reboot team successfully commanded the probe to switch into Engineering Mode to begin to broadcast telemetry.[35][36]

On June 26, project members using the Goldstone Deep Space Communications Complex DSS-24 antenna achieved synchronous communication and obtained the four ranging points needed to refine the spacecraft's orbital parameters.[37] The project team received approval from NASA to continue operations through at least July 16, and made plans to attempt the orbital maneuver in early July.[28][38]

On July 2, the reboot project fired the thrusters for the first time since 1987. They spun up the spacecraft to its nominal roll rate, in preparation for the upcoming trajectory correction maneuver in mid-July.[39][40]

On July 8, a longer sequence of thruster firings failed, apparently due to loss of the nitrogen gas needed to pressurize the fuel tanks.[11][12][13]

On July 24, the ISEE-3 Reboot Team announced that all attempts to change orbit using the ISEE-3 propulsion system had failed. Instead, the team said, the ISEE-3 Interplanetary Citizen Science Mission would gather data as the spacecraft flies by the Moon on August 10 and enters a heliocentric orbit similar to Earth's. The team began shutting down propulsion components to maximize the electrical power available for the science experiments.[41]

On July 30, the team announced that it still planned to acquire data from as much of ISEE-3's 300-day orbit as possible. With five of the 13 instruments on the spacecraft still working, the science possibilities included listening for gamma-ray bursts, where observations from additional locations in the Solar System can be valuable. The team was also recruiting additional receiving sites around the globe to improve diurnal coverage, in order to upload additional commands while the spacecraft is close to Earth and later to receive data.[42]

On August 10 at 18:16 UTC, the spacecraft passed about 15,600 km (9,700 mi) from the surface of the Moon. It will continue in its heliocentric orbit, and will return to the vicinity of Earth in 2031.[43]

Contact lost[]

On September 25, 2014, the Reboot team announced that contact with the probe was lost on September 16. It is unknown whether contact can be reestablished because the probe's exact orbit is uncertain. The spacecraft's post-lunar flyby orbit takes it further from the Sun, causing electrical power available from its solar arrays to drop, and its battery failed in 1981. Reduced power could have caused the craft to enter a safe mode, from which it may be impossible to awaken without the precise orbital location information needed to point transmissions at the craft.[14]

Spacecraft design[]

The ICE spacecraft is a barrel-like cylindrical shape covered by solar panels. Four long antennas protrude equidistant around the circumference of the spacecraft, spanning 91 metres (299 ft).[44] It has a dry mass of 390 kg (860 lb) and can generate nominal power of 173 watts.

Payload[]

ICE carries 13 scientific instruments to measure plasmas, energetic particles, waves, and fields.[2][17] As of July 2014, five were known to be functional. It does not carry a camera or imaging system. Its detectors measure high energy particles such as X- and gamma-rays, solar wind, plasma and cosmic particles. A data handling system gathers the scientific and engineering data from all systems in the spacecraft and formats them into a serial stream for transmission. The transmitter output power is five watts.

Scientific payload and experiments[]

- Solar Wind Plasma Experiment, failed after February 26, 1980

- Vector Helium Magnetometer

- Low Energy Cosmic Ray Experiment, designed to measure solar, interplanetary, and magnetospheric energetic ions

- Medium Energy Cosmic Ray Experiment, 1-500 MeV/n, Z = 1-28; Electrons: 2-10 MeV

- High Energy Cosmic Ray Experiment, H to Ni, 20-500 MeV/n

- Plasma Wave Instrument

- Low Energy Proton Experiment, also known as the Energetic Particle Anisotropy Spectrometer (EPAS), designed to study low-energy solar proton acceleration and propagation processes in interplanetary space

- Cosmic Ray Electrons and Nuclei

- X-Rays and Electrons Instrument, to provide continuous coverage of solar-flare X rays and transient cosmic gamma-ray bursts

- Radio Mapping Experiment, 30 kHz - 2 MHz, to map the trajectories of type III solar bursts

- Plasma Composition Experiment

- Heavy Isotope Spectrometer Telescope

- Ground Based Solar Studies Experiment

Publications[]

- Birmingham, Thomas J.; Dessler, Alexander J. (1998). Comet Encounters. American Geophysical Union. Bibcode:1998coen.book.....B. ISBN 978-1-118-66875-7.

- Ogilvie, K. W.; Durney, A.; von Rosenvinge, T. (July 1978). "Descriptions of Experimental Investigations and Instruments for the ISEE Spacecraft". IEEE Transactions on Geoscience Electronics. GE-16 (3): 151–153. Bibcode:1978ITGE...16..151.. doi:10.1109/TGE.1978.294535. S2CID 10197087.

- von Rosenvinge, Tycho T.; Brandt, John C.; Farquhar, Robert W. (April 1986). "The International Cometary Explorer Mission to Comet Giacobini-Zinner". Science. 232 (4748): 353–356. Bibcode:1986Sci...232..353V. doi:10.1126/science.232.4748.353. PMID 17792143. S2CID 45258658.

References[]

- ^ ISEE 3. NASA National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "ISEE-3/ICE". Solar System Exploration. NASA. Archived from the original on June 10, 2015.

- ^ Siddiqi, Asif A. (2018). Beyond Earth: A Chronicle of Deep Space Exploration, 1958–2016 (PDF). The NASA history series (second ed.). Washington, DC: NASA History Program Office. p. 2. ISBN 9781626830424. LCCN 2017059404. SP2018-4041.

- ^ Stelzried, C.; Efron, L.; Ellis, J. (July–September 1986). Halley Comet Missions (PDF) (Report). NASA. pp. 241–242. TDA Progress Report 42-87.

- ^ Robertson, Adi (May 23, 2014). "Spaceship come home: can citizen scientists rescue an abandoned space probe?". The Verge. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- ^ McKinnon, Mika (April 15, 2014). "Can This 1970s Spacecraft Explore Again?". io9.com. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- ^ "We do NOT like..." Twitter.com. June 25, 2014. Retrieved June 25, 2014.

- ^ Geuss, Megan (May 29, 2014). "ISEE-3 spacecraft makes first Earth contact in 16 years". Ars Technica. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ^ Matheson, Dan (May 2014). "Citizen-scientists look to reboot 35-year-old spacecraft". CTV News. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Chang, Kenneth (June 15, 2014). "Calling Back a Zombie Ship From the Graveyard of Space". The New York Times. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b McKinnon, Mika (July 10, 2014). "Distributed Rocket Science is a Thing Now". io9.com. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cowing, Keith (July 18, 2014). "Lost and Found in Space". The New York Times. The Opinion Pages. Retrieved July 18, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Chang, Kenneth (July 9, 2014). "Space Probe Might Lack Nitrogen to Push It Home". The New York Times. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cowing, Keith (September 25, 2014). "ISEE-3 is in Safe Mode". Space College. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

The ground stations listening to ISEE-3 have not been able to obtain a signal since Tuesday the 16th.

- ^ Siddiqi, Asif A. (2018). Beyond Earth: A Chronicle of Deep Space Exploration, 1958–2016 (PDF). The NASA history series (second ed.). Washington, DC: NASA History Program Office. p. 2. ISBN 9781626830424. LCCN 2017059404. SP2018-4041.

- ^ "ISEE 3". National Space Science Data Center. NASA. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "ISEE-3 / ICE (International Cometary Explorer) mission". eoPortal. European Space Agency. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ Stelzried, C.; Efron, L.; Ellis, J. (July–September 1986). Halley Comet Missions (PDF) (Report). NASA. pp. 241–242. TDA Progress Report 42-87.

- ^ Murdin, Paul, ed. (November 2000). "International Cometary Explorer (ICE)". Encyclopedia of Astronomy and Astrophysics. IOP Science. Bibcode:2000eaa..bookE4650.. doi:10.1888/0333750888/4650. hdl:2060/19920003890. ISBN 0333750888.

- ^ Reddy, Francis. "Comets". Astronomy.com. Archived from the original on June 7, 2010.

- ^ Thomson, Iain (April 24, 2014). "Privateers race to capture forgotten NASA space probe using crowdsourced cash". The Register. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- ^ Greene, Nick. "International Sun-Earth Explorer 3 - International Cometary Explorer". About.com. Archived from the original on July 12, 2014. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- ^ Lakdawalla, Emily (October 3, 2008). "It's Alive!". The Planetary Society.

- ^ Cowing, Keith (April 14, 2014). "ISEE-3 Reboot Project (IRP)". Space College.

- ^ Cowing, Keith (May 15, 2014). "ISEE-3 Reboot Project Passes Funding Goal". Space College.

- ^ Cowing, Keith (May 23, 2014). "ISEE-3 Reboot Project Completes Crowdfunding Drive". Space College.

- ^ Greenfieldboyce, Nell (March 18, 2014). "Space Thief Or Hero? One Man's Quest To Reawaken An Old Friend". National Public Radio.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "A Retired Satellite Gets Back To Work". National Public Radio. Here & Now. June 27, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ^ Wingo, Dennis (May 1, 2014). "ISEE-3 Reboot Project Technical Update 1 May 2014". Space College.

- ^ Lakdawalla, Emily (February 7, 2014). "ICE/ISEE-3 to return to an Earth no longer capable of speaking to it". The Planetary Society.

- ^ Seeber, Balint (July 7, 2014). "The ISEE-3 Reboot Project: a dream SDR application". Ettus Research. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Cowing, Keith (May 15, 2014). "ISEE-3 Reboot Project Status and Schedule for First Contact". Space College. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- ^ "ISEE-3 Reboot Project by Space College, Skycorp, and SpaceRef". RocketHub. May 20, 2014. Archived from the original on May 20, 2014. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- ^ Cole, Steve; Wingo, Dennis (May 21, 2014). "NASA Signs Agreement with Citizen Scientists Attempting to Communicate with Old Spacecraft" (Press release). NASA.

- ^ Neuman, Scott (May 29, 2014). "After Decades Of Silent Wandering, NASA Probe Phones Home". National Public Radio.

- ^ "Citizen Scientists Successfully Communicate with Spacecraft". NASA. May 30, 2014. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ^ Cowing, Keith (June 26, 2014). "ISEE-3 Status 26 June 2014: DSN Ranging Success". Space College. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- ^ Cowing, Keith (June 27, 2014). "ISEE-3 Status 27 June 2014: Another DSN Ranging Success". Space College.

- ^ "ISEE-3 Propulsion System Awakens at 11th Hour". SpaceNews.com. July 3, 2014. Archived from the original on July 7, 2014. Retrieved July 3, 2014.

- ^ "ISEE-3 Engines Fired For Spin-Up". Space College. July 2, 2014. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ^ Cowing, Keith (July 24, 2014). "Announcing the ISEE-3 Interplanetary Citizen Science Mission". Space College.

- ^ Howell, Elizabeth (July 30, 2014). "Vintage NASA Spacecraft to Tackle Interplanetary Science". Space.com.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (August 8, 2014). "Rudderless Craft to Get Glimpse of Home Before Sinking Into Space's Depths". The New York Times. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- ^ Cowing, Keith (June 7, 2014). "What ISEE-3 Really Looks Like". Space College.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to ISEE-3. |

- ISEE-3/ICE profile by NASA HEASARC

- ISEE-3/ICE profile by NASA Solar System Exploration

- ISEE-3 Reboot Project homepage at SpaceCollege.com

- A Spacecraft for All, an interactive site created in cooperation with Google to support the ISEE-3 Reboot Project

- 1978 in spaceflight

- Derelict space probes

- Satellites orbiting the Sun

- Missions to comets

- NASA space probes

- Spacecraft launched in 1978

- Explorers Program

- Spacecraft using halo orbits