Iron Eagle

| Iron Eagle | |

|---|---|

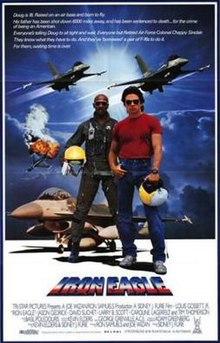

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Sidney J. Furie |

| Written by | Kevin Alyn Elders Sidney J. Furie |

| Produced by | Ron Samuels Joe Wizan Lou Lenart Kevin Alyn Elders |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Adam Greenberg |

| Edited by | George Grenville |

| Music by | Basil Poledouris |

Production companies | TriStar Pictures Delphi Films |

| Distributed by | TriStar Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 117 minutes |

| Countries | United States Canada |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $18 million |

| Box office | $24,159,872 (U.S.)[1] |

Iron Eagle is a 1986 military action film directed by Sidney J. Furie, co-written by Kevin Alyn Elders and starring Jason Gedrick and Louis Gossett Jr.[2] While it received mixed reviews, being unfavorably compared to the similarly-themed Top Gun released the same year, the film earned $24,159,872 at the U.S. box office. Iron Eagle was followed by three sequels: Iron Eagle II, Aces: Iron Eagle III, and Iron Eagle on the Attack, with Gossett being the only actor to appear in all four films.[3]

The basis of the story relates to real life attacks by the United States against Libya over the Gulf of Sidra, in particular the 1981 Gulf of Sidra incident.[citation needed]

Plot[]

Doug Masters, son of veteran U.S. Air Force pilot Col. Ted Masters, is a hotshot civilian pilot, hoping to follow in his father's footsteps. His hopes are dashed when he receives a notice of rejection from the Air Force Academy. Making matters worse is the news that his father has been shot down and captured by the fictional Arab state of Bilya while patrolling over the Mediterranean Sea.

Despite the incident occurring over international waters, the Arab state's court finds Col. Masters guilty of trespassing over their territory and sentences him to hang in three days. Seeing that the U.S. government will do nothing to save his father's life, Doug decides to take matters into his own hands and come up with his own rescue mission. He requests the help of Col. Charles "Chappy" Sinclair, a Vietnam veteran pilot currently in the Air Force Reserve, who, while not knowing Col. Masters personally, had a favorable run-in with him years prior to meeting Doug and "knew the type." Chappy is skeptical at first; but Doug convinces him that, with his friends, he has full access to the airbase's intelligence and resources and can give him an F-16 fighter for the mission. To Doug's surprise, Chappy had already begun planning a rescue operation himself after he learned the outcome of Col. Masters' trial. The combined efforts of Chappy and Doug's team result in a meticulously planned mission and the procurement of two heavily armed F-16B jets, with Doug flying the second unit.

On the day of Col. Masters' scheduled execution, Doug and Chappy fly their jets to the Mediterranean Sea and cross into Bilyan airspace. The Bilyan military responds, and in the ensuing battle Doug and Chappy take out three MiG-23 fighters and destroy an airfield, with Chappy's plane being hit by anti-aircraft fire. He tells Doug to climb to a high altitude and play the tape he made him the night before, then his engine fails and Doug listens as Chappy's fighter goes down. Chappy's recorded voice gives Doug encouragement and details that help him to complete the mission and rescue his father. Making the enemy believe he is leading a squadron, Doug threatens the enemy state into releasing his father for pickup.

Before Doug lands his F-16, Col. Masters is shot by a sniper, causing Doug to destroy the airbase and engulf the runway with napalm to keep the army at bay while he lands and picks up his wounded father. Just as they take off, Doug and his father encounter another group of MiGs led by Col. Akir Nakesh, himself an ace pilot. The lone F-16 and Nakesh's MiG engage in a dogfight until a missile from Doug finishes off Nakesh. Low on fuel and ammunition, the F-16 is pursued by the other enemy MiGs when a squadron of U.S. Air Force F-16s appear, warding off the MiGs before escorting Doug and his father to Ramstein Air Base in West Germany.

While Col. Masters is being treated for his wounds, Doug is reunited with Chappy, who had ejected from his plane and was picked up by an Egyptian fishing trawler. The two are summoned by an Air Force judiciary panel for their reckless actions. Seeing that any form of punishment for the duo would expose an embarrassing lapse in Air Force security, the panel forgoes prosecution as long as Doug and Chappy never speak of their operation to anyone. In addition, Chappy convinces the panel to grant Doug admission to the Air Force Academy. Days later, a plane assigned by the President returns to the U.S., reuniting Doug, Chappy, and Col. Masters with family and friends.

Cast[]

- Louis Gossett Jr. as Colonel Charles 'Chappy' Sinclair

- Jason Gedrick as Doug Masters

- David Suchet as Ministry of Defense Colonel Akir Nakesh

- Shawnee Smith as Joenie

- Melora Hardin as Katie

- Larry B. Scott as Reggie

- Lance LeGault as General Edwards

- Tim Thomerson as Colonel Ted Masters

- Caroline Lagerfelt as Elizabeth Masters

- Robert Jayne as Matt Masters

- Jerry Levine as Tony

- Robbie Rist as Milo Bazen

- Michael Bowen as Knotcher

- David Greenlee as Kingsley

- Tom Fridley as Brillo

- Rob Garrison as Packer

- Michael Alldredge as Colonel Blackburn

Production[]

According to writer/director Sidney J. Furie, the film's working title was Junior Eagle. The script was turned down by every studio before it was picked up by Joe Wizan, former head of 20th Century Fox. Wizan then handed the script to producer Ron Samuels, who likened it to the old John Wayne westerns.[2] Pre-production work began in late 1984.[4]

Although their F-16s are featured in the movie poster, the United States Air Force has a long-standing policy about not cooperating on any film involving the theft of an aircraft.[5] Consequently, the filmmakers turned to the Israeli Air Force for the necessary aerial sequences. The filming in Israel took six weeks, with the flight sequences choreographed by Jim Gavin, whose earlier works include Blue Thunder.[2]

Filming took place at both California and Israeli locales. To simulate the above-ground facilities of a typical USAF base, a combination of hangars and barracks at Camarillo and the Planes of Fame Air Museum at Chino, California were employed. Most Israeli airbases are situated in underground hangars, maintenance shops and crew quarters.[6]

The aircraft used for both the American and the Bilyan air forces were Israeli jets: single-seat F-16As, two-seat F-16Bs, and F-21/C-2 Kfirs simulating MiG-23s, painted with fictional national markings.[7][N 1] [N 2] The "Hades" bomb employed by Masters against the Bilyan airfield was a fictional weapon, although its effects were similar to real-life napalm.[citation needed]

The character of Colonel Charles "Chappy" Sinclair was likely inspired by the real life U.S. Air Force General Daniel "Chappie" James, Jr. James was a member of the famed all-black Tuskegee Airmen, and also flew fighter jets in the Korean War and the Vietnam War. He later became the first black four-star general in U.S. history.[citation needed]

Soundtrack[]

The soundtrack album was issued by Capitol Records on LP and cassette, and later on compact disc. It features songs by Queen, King Kobra, Eric Martin, Dio, Adrenalin, George Clinton and more.

In 2008, Varèse Sarabande released the original musical score by Basil Poledouris as part of their CD Club.

Reception[]

Box office[]

Iron Eagle earned $24,159,872 at the U.S. box office.[1] Although the movie was not a major success at the cinema, it generated $11 million in home video sales, enough to justify a sequel.[8]

Critical response[]

Film reviewers were generally negative; Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times called the film "ludicrous", "preposterous", and "a total waste of time", saying it "achieves a kind of perfection of awfulness that only earnest effort can produce".[9]

Film historian and reviewer Leonard Maltin dismissed the film as "...a dum-dum comic-book movie...full of jingoistic ideals and dubious ethics, along with people who die and then miraculously come back to life. Not boring, just stupid."[10]

Joe Kane, aka "The Phantom of the Movies", seemed to agree: "...Iron Eagle boasts the hottest rock score of any war film since Apocalypse Now. Alas, the similarity ends there. Forget the picture and buy the soundtrack album instead; King Kobra's titular music video, Never Say Die, is better made than the movie itself."[11]

Variety magazine commented that the film has "breakneck action and some dandy dogfights", but the dialogue is "simply laughable".[12]

Janet Maslin of the New York Times, on the other hand, gave the film a favorable review, saying it has a "fun-loving feeling" and "something for everyone", appealing to teenagers as well as military aviation buffs for the "skillfully done" aerial combat sequences, along with the heartwarming, fatherly-like interracial relationship between Chappy and young Doug.[13]

Although user reviews generally gave the film a 56% rating, on Rotten Tomatoes the film has a rating of 20% based on reviews from five critics.[14]

Home media[]

Iron Eagle was released on VHS, Betamax, and LaserDisc by CBS/FOX Video in 1986. On October 1, 2002, it was released on DVD and on February 3, 2009, it was reissued on DVD by Sony Pictures Home Entertainment in a double-feature set with the 1993 film Last Action Hero.[15]

References[]

Notes[]

- ^ The F-16s were given American national roundels and tail codes that only superficially resembled actual USAF markings, but retained their Israeli desert camouflage, a paint scheme that has never been used on USAF F-16s.

- ^ The cockpit displays depicted in the film were all simulated, and did not bear any resemblance to an early model F-16's actual instrumentation (with the exception of the heads-up display, which was somewhat accurate).

Citations[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Box office: Iron Eagle." BoxOfficeMojo, November 3, 1986. Retrieved: May 20, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mann, Roderick. "Sidney Furie leads the cheer for 'Iron Eagle'." Los Angeles Times, February 2, 1986. Retrieved: October 27, 2010.

- ^ Orriss 2018, p. 180.

- ^ Orris 2018, p. 180.

- ^ Powell, Larry. "The Making of Iron Eagle." Air Classics, Volume 22, No. 2, February 1986, p. 72.

- ^ Powell, Larry. "The Making of Iron Eagle." Air Classics, Volume 22, No. 2, February 1986, p. 73.

- ^ Beck 2016, p. 122.

- ^ "Cassette sales help `Iron Eagle II` to fly." New York Daily News, January 16, 1987. Retrieved: May 20, 2019.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (January 17, 1986). "'Iron Eagle': Middle-east rescue mission". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2020-02-19.

- ^ Maltin 2006, p. 660.

- ^ The Phantom's Ultimate Video Guide, 19

- ^ "Review: 'Iron Eagle'". Variety. December 31, 1985. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved 2020-02-19.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (January 18, 1986). ""Iron Eagle", a tale of teen-age military rescue". New York Times. Retrieved 2020-02-19.

- ^ "Iron Eagle." rottentomatoes.com. Retrieved: May 20, 2019.

- ^ " 'Last Action Hero'; 'Iron Eagle' DVD." CDUniverse.com, February 3, 2009. Retrieved: May 20, 2019.

Bibliography[]

- Beck, Simon D. The Aircraft-Spotter's Film and Television Companion. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2016. ISBN 9-781476-663494.

- Maltin, Leonard. Leonard Maltin's 2007 Movie Guide. New York: New American Library, 2006. ISBN 978-0-451-21916-9.

- Orriss, Bruce. When Hollywood Ruled the Skies: The Post World War II Years. Hawthorne, California: Aero Associates Inc., 2018. ISBN 978-0-692-03465-1.

External links[]

- 1986 films

- English-language films

- Iron Eagle (film series)

- 1980s action films

- American films

- American action war films

- American aviation films

- American coming-of-age films

- Canadian action films

- Canadian aviation films

- Canadian films

- Cold War aviation films

- Films directed by Sidney J. Furie

- Films scored by Basil Poledouris

- Films set in a fictional country

- Films set in the Mediterranean Sea

- Films set in the United States

- Films shot in Israel

- Films about the United States Air Force

- TriStar Pictures films