Island of Lost Souls (1932 film)

| Island of Lost Souls | |

|---|---|

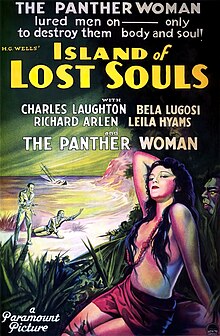

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Erle C. Kenton |

| Written by |

|

| Based on | The Island of Doctor Moreau by H. G. Wells |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Karl Struss |

| Music by | Arthur Johnston Sigmund Krumgold |

Production company | Paramount Pictures |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 71 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Island of Lost Souls is a 1932 American pre-Code science-fiction horror film, and the first sound film adaptation of H. G. Wells' 1896 novel The Island of Dr. Moreau. Produced by Paramount Pictures, the film was directed by Erle C. Kenton, from a script co-written by science fiction author Philip Wylie. It stars Charles Laughton, Richard Arlen, Leila Hyams, Bela Lugosi, and Kathleen Burke. The plot centers on a remote South Pacific island where mad scientist, Dr. Moreau, secretly conducts experiments to accelerate evolution in plants and animals, with horrific consequences.

Featuring depictions of cruelty, animal-human hybrids, and irreligious ideas, the release of Island of Lost Souls was embroiled in controversy. Banned in some countries for decades, Island of Lost Souls has become an influential film and has acquired cult film status.[1]

Plot[]

Shipwrecked traveler Edward Parker is rescued by a freighter delivering animals to an isolated South Seas island owned by Dr. Moreau. After Parker fights with the freighter's drunken captain for his mistreating M'ling, a passenger with some bestial features, the captain tosses Parker overboard into Mr. Montgomery's boat, bound for Moreau's island.

When Parker arrives at the island, Moreau welcomes Parker to his home and introduces him to Lota, a young woman whom Moreau claims is of Polynesian origin, and who seems shy and withdrawn. When she and Parker hear screams coming from another room, which Lota calls "the House of Pain," Parker investigates. He sees Moreau and Moreau's assistant, Montgomery, operating on a humanoid creature without anesthetic. Convinced that Moreau is engaged in sadistic vivisection, Parker tries to leave, only to encounter brutish-looking humanoids resembling apes, felines, swine, and other beasts emerging from the jungle. Moreau appears, cracks his whip, and orders them to recite a series of rules ("the Law"). Afterward, the strange "men" disperse.

Back in the main house, the doctor tries to assuage Parker by explaining his scientific work—that he started experimenting in London years ago, accelerating the evolution of plants. He then progressed to animals, trying to transform them into humans through plastic surgery, blood transfusions, gland extracts, and ray baths. When a dog-hybrid escaped from his laboratory it so horrified people that he was forced to leave England.

Moreau confides to Parker that Lota is the sole female on the island, but hides that she was derived from a panther. Later he privately expresses his excitement to Montgomery that Lota is showing human emotions in her attraction to Parker. So he can keep observing this process, Moreau ensures that Parker cannot leave by destroying the only available boat, placing blame for this on his beast-men.

As Parker spends time with Lota, she falls in love with him. Eventually the two kiss, but Parker is then stricken with guilt, since he still loves his fiancée, Ruth Thomas. As Lota hugs him, Parker examines her fingernails, which are reverting to animalistic claws. He storms into the office of Dr. Moreau to confront him for hiding the truth about Lota. Dr. Moreau explains that Lota is his most nearly human creation, and he wanted to see if she was capable of falling in love with a man and bearing humanlike children. Enraged by the deceit, Parker punches Moreau to the ground and demands to leave the island. When Moreau realizes Lota is beginning to revert to her panther origin, he first despairs, believing that he has failed—until he notices Lota weeping, showing human emotion. His hopes are raised and he screams that he will "burn out" the remaining animal in her in the House of Pain.

Meanwhile, the American consul at Apia in Samoa, Parker's original destination, learns about Parker's location from the cowed freighter captain. Fiancée Ruth Thomas persuades Captain Donahue to take her to Moreau's island. She is reunited with Parker, but Moreau persuades them to stay the night. The ape-themed Ouran, one of Moreau's creations, tries to break into Ruth's room. She wakes up and screams for help, and Ouran is driven away. Montgomery confronts Moreau, and implies that Ouran's attempted break-in was arranged by Moreau. Donahue offers to try to reach the ship and fetch his crew. Moreau, seeing him depart, dispatches Ouran to strangle him.

Learning that Moreau has allowed Ouran to break the Law, the other beast-men no longer feel bound by it. They set their huts ablaze and defy Moreau, who tries and fails to regain control. He demands of them, "What is the Law?" Their response is, "Law no more!" The beast-men drag the doctor into his House of Pain, where they bind him, screaming, to the operating table and brutally stab him to death with his own surgical knives.

With help from the disaffected Montgomery, Parker and Ruth make their escape. Parker insists they take Lota along. When Lota sees Ouran following, she waits in ambush. In the ensuing struggle, both are killed. The others escape by boat as the island goes up in flames, presumably destroying Moreau's work and eradicating the beast-men.

Cast[]

- Charles Laughton as Dr. Moreau

- Richard Arlen as Edward Parker

- Leila Hyams as Ruth Thomas

- Bela Lugosi (billed as Bela "Dracula" Lugosi in the trailer) as Sayer of the Law

- Kathleen Burke as Lota, the Panther Woman

- Arthur Hohl as Mr. Montgomery

- Stanley Fields as Captain Davies

- Paul Hurst as Captain Donahue

- Hans Steinke as Ouran

- Tetsu Komai as M'ling, Moreau's loyal house servant

- George Irving as The Consul

Production[]

Paramount Pictures saw the film as a way to take advantage of the horror film boom in the early-1930s. In its publicity material the studio played up the possibility of "creative biology" as a promotional device with a publicity feature titled "Science Tries to Create Life!" The filmmakers invited evolutionary biologist Julian Huxley on to their set to get his approval of the scientific accuracy of their film.[2]

Release[]

Island of Lost Souls opened theatrically in the United States in late December 1932, with showings beginning in Tucson, Arizona on Christmas Eve.[a] It continued to open in various cities over the next week, premiering in Groton, Vermont on December 28, 1932,[4] and Bristol, Tennessee on December 30, 1932.[5]

Censorship[]

When the film was reviewed in 1932 by the relatively permissive pre-Code era Hays Office, it was passed, noting that some state censorship boards might object to a line that suggests Dr. Moreau knows what it was like to be like God. Instead, 14 states fully rejected the film for that profane statement and its full acceptance of the then-controversial theory of human evolution.[6] When the film was reissued in 1941, it was submitted for review to the Production Code Administration which strictly enforced the restrictions in the Motion Picture Production Code. To obtain approval to release the film, all dialogue suggesting that Dr. Moreau in any way created the beast-men was cut.[6]

The film was examined and refused a certificate three times by the British Board of Film Censors, in 1933, 1951, and 1957. The reason for the initial ban was due to scenes of vivisection; it is likely that the Cinematograph Films (Animals) Act 1937, which forbade the portrayal of cruelty to animals in feature films released in Britain, was a significant factor in the BBFC's subsequent rejections. Among the BBFC objections were references to "cutting a living man to pieces", and Dr. Moreau saying "Do you know what it means to feel like God?" They also felt the film's showing biological evolution under human control was "repulsive" and "unnatural".[7]

By April 1933, the film was banned in Sweden and Denmark.[8] In Australia, racism determined viewership: white Australians were allowed to see the film, while Aboriginal Australians were not.[8]

The book's author H. G. Wells was outspoken in his dislike of the film adaptation, feeling the overt horror elements overshadowed the story's deeper philosophical import. "And he responded with open satisfaction when the film was banned in England."[9]

The film was eventually approved for UK showings with an 'X' certificate on July 9, 1958, after cuts were made.[10][11] It was later classified as PG when reissued on DVD in 2011 with the cuts restored.

Reception[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (November 2017) |

Audience and critical reactions in 1932-3 varied widely. While the New York Times critic Mordaunt Hall found much to like,[12] many exhibitors and theater viewers in small-town America detested it: "No excuse for making a production of this kind.”[13] Other newspapers reviews were unimpressed with its graphic nature. The New York Evening Post published a review that included the line: “The picture strains too much for its horror effects.”[14]

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 88% based on 40 reviews, with a weighted average rating of 8.6/10. Its consensus reads: "Led by a note-perfect performance from Charles Laughton, Island of Lost Souls remains the definitive film adaptation of its classic source material."[15]

Influence[]

Two films have since been made based on the same H. G. Wells novel. The first was released in 1977 and stars Burt Lancaster as the doctor. The second came out in 1996, with Marlon Brando as Moreau. In the very similar The Twilight People (1973), actress Pam Grier played the panther woman. On top of that, the panther woman wasn't a part of the original novel, but was apparently popular with later filmmakers to include her in future adaptations.

Playwright Charles Ludlam was influenced by this movie, as well as Wells' novel, and the fairy tale by Charles Perrault, when writing his play Bluebeard (1970).[16]

Members of the new wave band Devo were fans of the film. The "What is the law?" sequence formed part of the lyrics to Devo's song "Jocko Homo," with Lugosi's query "Are we not men?" providing the title to their 1978 debut album Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo! Devo's short film "The Truth About De-Evolution" and an interview with founding members Gerald Casale and Mark Mothersbaugh are special features on the Criterion Collection 2011 re-release of the film on DVD and Blu-ray.[17]

Oingo Boingo is another new wave band who paid tribute to the film with their song "No Spill Blood," which featured the refrain "What is the Law? No spill blood!" and appeared on their 1983 album, Good for Your Soul.

The Meteors, a psychobilly band from the UK told the story of the film in their song "Island of Lost Souls" on their 1986 album Teenagers From Outer Space, the chorus being a prolonged chant of "We don't eat meat; Are We Not Men? We stand on two feet; Are We Not Men?" etc.

Heavy metal band Van Halen paid homage to the film in the original version of their song "House of Pain", the early lyrics for which directly referenced the storyline of the movie. During onstage introductions of the song circa 1976–77, Van Halen vocalist David Lee Roth routinely gave a brief synopsis of the film. The song was shelved for the better part of a decade, but eventually resurfaced with different non-movie-related lyrics on the band's 1984 album.

The US horror-rock band Manimals based much of their stage persona on the film. Their 1985 Blood is the Harvest vinyl E.P. closes with the song "Island of Lost Souls", which includes a line "What is the Law?" that fans would chant during live shows.[18] The film historian Gary D. Rhodes has called them "the best-ever in the horror-rock genre" and referenced them in his 1997 book Lugosi (McFarland Press).

See also[]

Notes[]

References[]

- ^ "Cult Movies". The Criterion Collection. Archived from the original on April 13, 2019. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ Kirby, David (2002). "Are We Not Men?: The Horror of Eugenics in The Island of Dr. Moreau". Paradoxa. 17: 93–108.

- ^ "At the Theatres This Week". Arizona Daily Star. December 18, 1932. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Big Double Feature Program of Unusual Hits". Groton Times. December 23, 1932. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Helen Hayes Has Part in "Farewell to Arms;" Cantor, Barrymore, Others to Be Here in Films". The Bristol Herald Courier. December 25, 1932. p. 12 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Kirby, David (2013), "Censoring Science in 1930s and 1940s Hollywood Cinema", in Nelson, Donna J.; Grazier, Robert; Paglia, Jaime; Perkowitz, Sidney (eds.), Hollywood Chemistry: When Science Met Entertainment, American Chemical Society, pp. 229–240, ISBN 978-0-8412-2824-5

- ^ Skal, David J. (1993). The Monster Show : a Cultural History of Horror (1st ed.). New York: Norton. ISBN 0393034194. OCLC 25914002.

- ^ a b Johnson, Tom (July 5, 2006). Censored Screams: The British Ban on Hollywood Horror in the Thirties. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-7864-2731-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Kingsley, Liz (February 18, 2019). "Island Of Lost Souls 1933". and you call yourself a scientist!? [blog].

- ^ Robertson, James C. (1989). The Hidden Cinema: British Film Censorship in Action, 1913-1975. London: Routledge. pp. 55–57. ISBN 0415090342.

- ^ Robertson, James C. (1985). The British Board of Film Censors: Film Censorship in Britain, 1896-1950. Dover, New Hampshire: Croom Helm. ISBN 0709922701.

- ^ Hall, Mordaunt (January 13, 1933). "Charles Laughton As a Mad Scientist". New York Times.

- ^ Long, Derek (October 22, 2015). "ISLAND OF LOST SOULS: Vivisection, Panther Women, and the Studio System".

- ^ Johnson, Tom (July 5, 2006). Censored Screams: The British Ban on Hollywood Horror in the Thirties. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-7864-2731-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Island of Lost Souls (1933) - Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes.com. Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ Gussow, Mel (November 15, 1991). "Bluebeard Legend As Retold By Ludlam". New York Times.

- ^ "Island Of Lost Souls DVD". 2011.

- ^ "Island Of Lost Souls song lyrics". 1985. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

Sources[]

- Island of Lost Souls VHS tape, Universal Home Video Monsters Classic Collection

- IMDb profile: Island of Lost Souls

- Everson, William K. (1974). Classics of the Horror Film: From the Days of the Silent Film to the Exorcist. Diane Publishing Company. ISBN 0788167316.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Island of Lost Souls (1932 film). |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Island of Lost Souls (1932 film) |

- Island of Lost Souls at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Island of Lost Souls at IMDb

- Island of Lost Souls at the TCM Movie Database

- Island of Lost Souls at AllMovie

- Island of Lost Souls: The Beast Flesh Creeping Back an essay by Christine Smallwood at the Criterion Collection

- Spanish language poster

- Kathleen Burke Wins Nationwide Contest! The Road to Panther Woman in Island of Lost Souls

- 1932 films

- English-language films

- Films directed by Erle C. Kenton

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- 1932 horror films

- 1930s science fiction horror films

- American science fiction horror films

- American black-and-white films

- American films

- Films based on horror novels

- Films based on works by H. G. Wells

- Films set in Oceania

- Films shot in Los Angeles County, California

- Mad scientist films

- American monster movies

- Films set on fictional islands

- Paramount Pictures films

- Films with screenplays by Philip Wylie