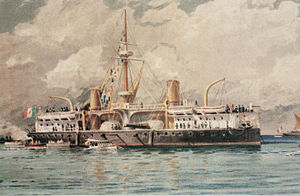

Italian ironclad Ruggiero di Lauria

Painting of Ruggiero di Lauria

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Ruggiero di Lauria |

| Namesake | Roger of Lauria |

| Builder | Regio Cantiere di Castellammare di Stabia |

| Laid down | 3 August 1881 |

| Launched | 9 August 1884 |

| Completed | 1 February 1888 |

| Stricken | 11 November 1909 |

| Fate | Sunk in shallow water 1943 |

| Notes | Served as floating oil tank GM45, 1909–1943 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Ruggiero di Lauria-class ironclad battleship |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 105.9 m (347 ft 5 in) length overall |

| Beam | 19.84 m (65 ft 1 in) |

| Draft | 8.29 m (27 ft 2 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 2-shafts, 2 compound steam engines |

| Speed | 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph) |

| Endurance | 2,800 nautical miles (5,186 km) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement | 507–509 |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

Ruggiero di Lauria was an ironclad battleship built in the 1880s for the Italian Regia Marina (Royal Navy). She was the lead ship of the Ruggiero di Lauria class, which included two other ships, Francesco Morosini and Andrea Doria. Ruggiero di Lauria, named for the medieval Sicilian admiral Ruggiero di Lauria, was armed with a main battery of four 17-inch (432 mm) guns, was protected with 17.75-inch (451 mm) thick belt armor, and was capable of a top speed of 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph).

The ship's construction period was very lengthy, beginning in August 1881 and completing in February 1888. She was quickly rendered obsolescent by the new pre-dreadnought battleships being laid down and, as a result, her career was limited. She spent her career alternating between the Active and Reserve Squadrons, where she took part in training exercises each year with the rest of the fleet. The ship was stricken from the naval register in 1909 and converted into a floating oil tank. She was used in this capacity until 1943, when she was sunk by bombs during World War II. The wreck was eventually raised and scrapped in 1945.

Design[]

Ruggiero di Lauria was 105.9 meters (347 ft 5 in) long overall and had a beam of 19.84 m (65 ft 1 in) and an average draft of 8.29 m (27 ft 2 in). She displaced 9,886 long tons (10,045 t) normally and up to 10,997 long tons (11,173 t) at full load. Her propulsion system consisted of a pair of compound steam engines each driving a single screw propeller, with steam supplied by eight coal-fired, cylindrical fire-tube boilers. Her engines produced a top speed of 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph) at 10,591 indicated horsepower (7,898 kW). She could steam for 2,800 nautical miles (5,200 km; 3,200 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). She had a crew of 507–509 officers and men.[1]

Ruggiero di Lauria was armed with a main battery of four 17 in (432 mm) /27 guns, mounted in two pairs en echelon in a central barbette. She carried a secondary battery of two 6-inch (152 mm) /32 guns, one at the bow and the other at the stern, and four 4.7 in (119 mm) /32 guns. As was customary for capital ships of the period, she carried five 14 in (356 mm) torpedo tubes submerged in the hull.[1]

She was protected by belt armor that was 17.75 in (451 mm) thick, an armored deck that was 3 in (76 mm) thick, and her conning tower was armored with 9.8 in (249 mm) of steel plate. The barbette had 14.2 in (361 mm) of steel armor.[1]

Service history[]

Construction – 1895[]

Ruggiero di Lauria was laid down at the Regio Cantiere di Castellammare di Stabia shipyard on 3 August 1881 and launched on 9 August 1884. She was not completed for another three and a half years, her construction finally being finished on 1 February 1888. Because of the rapid pace of naval technological development in the late 19th century, her lengthy construction period meant that she was an obsolete design by the time she entered service.[1] The year after she entered service, the British began building the Royal Sovereign class, the first pre-dreadnought battleships, which marked a significant step forward in capital ship design. In addition, technological progress, particularly in armor production techniques—first Harvey armor and then Krupp armor—rapidly rendered older vessels like Ruggiero di Lauria obsolete.[2]

The ship served with the 1st Division of the during the 1893 fleet maneuvers, along with the ironclad Lepanto, which served as the divisional flagship, the torpedo cruisers Euridice and Monzambano, and four torpedo boats. During the maneuvers, which lasted from 6 August to 5 September, the ships of the Active Squadron simulated a French attack on the Italian fleet.[3] Beginning on 14 October 1894, the Italian fleet, including Lepanto, assembled in Genoa for a naval review held in honor of King Umberto I at the commissioning of the new ironclad Re Umberto. The festivities lasted three days.[4] In 1895, Ruggiero di Lauria, the ironclad Sardegna, and the torpedo cruiser Partenope were assigned to the 2nd Division of the Italian fleet in the .[5] At the time, the ships of the Reserve Squadron were based in La Spezia.[6] Ruggiero di Lauria joined the ironclads Re Umberto, Sardegna, and Andrea Doria and the cruisers Stromboli, Etruria, and Partenope for a visit to Spithead in the United Kingdom in July 1895.[7] Later that year, the squadron stopped in Germany for the celebration held to mark the opening of the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal.[8]

1897–1945[]

In February 1897, the Great Powers formed the International Squadron, a multinational force made up of ships of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, French Navy, Imperial German Navy, Regia Marina, Imperial Russian Navy, and British Royal Navy that intervened in the 1897-1898 Greek uprising on Crete against rule by the Ottoman Empire. Ruggiero di Lauria deployed to Cretan waters as part of the Italian contribution to the squadron. In March 1897, she broke up a threat to Ottoman Army forces by Cretan insurgents at Heraptera (now Ierapetra) by threatening to bombard the insurgents.[9]

For the periodic fleet maneuvers of 1897, Ruggiero di Lauria was assigned to the First Division of the Reserve Squadron, which also included the ironclads Duilio and Lepanto and the protected cruiser Lombardia.[10] The following year, the Reserve Squadron consisted of Ruggiero di Lauria, Francesco Morosini, Lepanto, and five cruisers.[11] In 1899, Ruggiero di Lauria, Andrea Doria, Sicilia, and Sardegna took part in a naval review in Cagliari for the Italian King Umberto I, which included a French and British squadron as well.[12] That year, Ruggiero di Lauria and her two sisters served in the Active Squadron, which was kept in service for eight months of the year, with the remainder spent with reduced crews. The Squadron also included the ironclads Re Umberto, Sicilia, and Lepanto.[13] In 1900, Ruggiero di Lauria and her sisters were significantly modified and received a large number of small guns for defense against torpedo boats. These included a pair of 75 mm (3 in) guns, ten 57 mm (2.2 in) 40-caliber guns, twelve 37 mm (1.5 in) guns, five 37 mm revolver cannon, and two machine guns.[1]

In 1905, Ruggiero di Lauria and her two sisters were joined in the Reserve Squadron by the three Re Umberto-class ironclads and Enrico Dandolo, three cruisers, and sixteen torpedo boats. This squadron only entered active service for two months of the year for training maneuvers, and the rest of the year was spent with reduced crews.[14] During the annual training maneuvers in October 1906, a severe storm swept a man overboard, drowning him. During a gunnery competition held during the maneuvers, Ruggiero di Lauria's gunners came in last place.[15] In 1908, the Italian Navy decided to discard Ruggiero di Lauria and her sister Francesco Morosini.[16] The former was stricken from the naval register on 11 November 1909.[1] The ship was then converted into a floating oil depot. She was renamed GM45 and stationed at La Spezia until 1943, when she was sunk in shallow water by an air raid during World War II. Her wreck was scrapped after the end of the war in 1945.[17]

Notes[]

- ^ a b c d e f Gardiner, p. 342

- ^ Sondhaus, pp. 107–108, 111

- ^ Clarke & Thursfield, pp. 202–203

- ^ Garbett 1894, p. 1295.

- ^ Brassey (1896), p. 134

- ^ Garbett (1895), pp. 89–90

- ^ Neal, p. 155

- ^ Sondhaus, p. 131

- ^ di Mariano, Gabriele (1975). "CANEVARO, Felice Napoleone". treccani.it. Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (in Italian). Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- ^ Garbett (1897), p. 789

- ^ Garbett (1898), p. 200

- ^ Robinson, pp. 154–155

- ^ Brassey (1899), p. 72

- ^ Brassey (1905), p. 45

- ^ Brassey (1907), pp. 110–111

- ^ Brassey (1908), p. 31

- ^ Gardiner & Gray, p. 256

References[]

- Brassey, Thomas A., ed. (1896). The Naval Annual (Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.).

- Brassey, Thomas A., ed. (1899). The Naval Annual (Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.).

- Brassey, Thomas A, ed. (1905). "Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 40–57. OCLC 937691500.

- Brassey, Thomas A., ed. (1907). The Naval Annual (Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.).

- Brassey, Thomas A., ed. (1908). The Naval Annual (Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.).

- Clarke, George S. & Thursfield, James R. (1897). The Navy and the Nation, or, Naval Warfare and Imperial Defence. London: John Murray. OCLC 640207427.

- Garbett, H., ed. (November 1894). "Naval and Military Notes". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher. XXXVIII (201): 193–206. OCLC 8007941.

- Garbett, H., ed. (1895). "Naval and Military Notes – Italy". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher. XXXIX: 81–111. OCLC 8007941.

- Garbett, H., ed. (June 1897). "Naval Notes". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher & Co. XLI (232): 779–792. OCLC 8007941.

- Garbett, H., ed. (1898). "Naval Notes – Italy". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher. XLII: 199–204. OCLC 8007941.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-133-5.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-907-3.

- Neal, William George, ed. (1896). The Marine Engineer (London: Office for Advertisements and Publication) XVII.

- Robinson, Charles N., ed. (1899). "The French and Italian Fleets at Cagliari". The Navy and Army Illustrated. London: Hudson & Kearns. VIII (118): 154–155.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (2014). Navies of Europe. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-86978-8.

- Warship International Staff (2015). "International Fleet Review at the Opening of the Kiel Canal, 20 June 1895". Warship International. LII (3): 255–263. ISSN 0043-0374.

External links[]

- Ruggero di Lauria (1884) Marina Militare website

- Ruggiero di Lauria-class battleships

- 1884 ships

- Ships built in Castellammare di Stabia

- Battleships sunk by aircraft